Over the last half-century, the study of “cognitive bias” has expanded into a sprawling catalogue. Popular texts and psychology handbooks now list scores of them — anchoring, availability, framing, confirmation, bandwagon, hindsight, and dozens more. Each is defined descriptively, often accompanied by an experimental vignette. Collectively, these lists help us notice recurring distortions in judgment.

Yet something remains unsatisfying. For all their usefulness, bias lists feel like a museum of curiosities: one more labelled exhibit, another quirky demonstration of human fallibility. They rarely cohere into a framework that allows genuine clarity or mastery. At best, they are memorable examples; at worst, they become trivia. More troubling still, they often invite the assumption that the mind is essentially irrational and ungoverned by any deeper order.

Submetaphysics begins from another vantage. If bias is not just a quirk but a displacement, then every bias must presuppose a rightful referent — a ground that has been obscured or substituted. The real question is not simply “what bias occurred?” but “what ontological operator was displaced, and what proxy was installed in its place?”

Biases only appear puzzling when we treat them as arbitrary. Seen through a claritic lens — the discipline of disambiguation — their structure comes into focus. Every bias can be described in three parts:

Operator: the fundamental category at stake — truth, value, fairness, evidence, safety, justice.

Proxy: the substitute or shortcut installed in place of the operator — consensus, authority, sentiment, resemblance, immediacy, narrative.

Ontological Reset: the act of re-anchoring the operator in its true referent, collapsing the proxy’s apparent authority.

Take the bandwagon effect. On its face, it looks like an error of “following the crowd.” In claritic terms, however, the operator is truth. The proxy is consensus. The ontological reset is simple and devastating: truth is correspondence to reality, not popularity. Once this is restored, the bandwagon loses its grip.

The advantage of this approach is twofold: it reduces the apparent chaos of “hundreds of biases” to a limited number of operator categories, and it provides a repeatable method of correction. Instead of memorising a catalogue, one can carry a compass.

Traditional taxonomies divide biases into “families” — perceptual, social, affective, moral. Useful descriptively, but ontologically they blur the real structure. If every bias is a displacement of operator by proxy, then the decisive question is: does the distortion confront the agent from outside (world, others, interface), or arise within the agent (affect, judgment)?

This yields a fivefold framework, ordered by ontological priority. The sequence begins with the most immediate confrontation — the world as affect-laden — and moves progressively inward to the level of moral judgment.

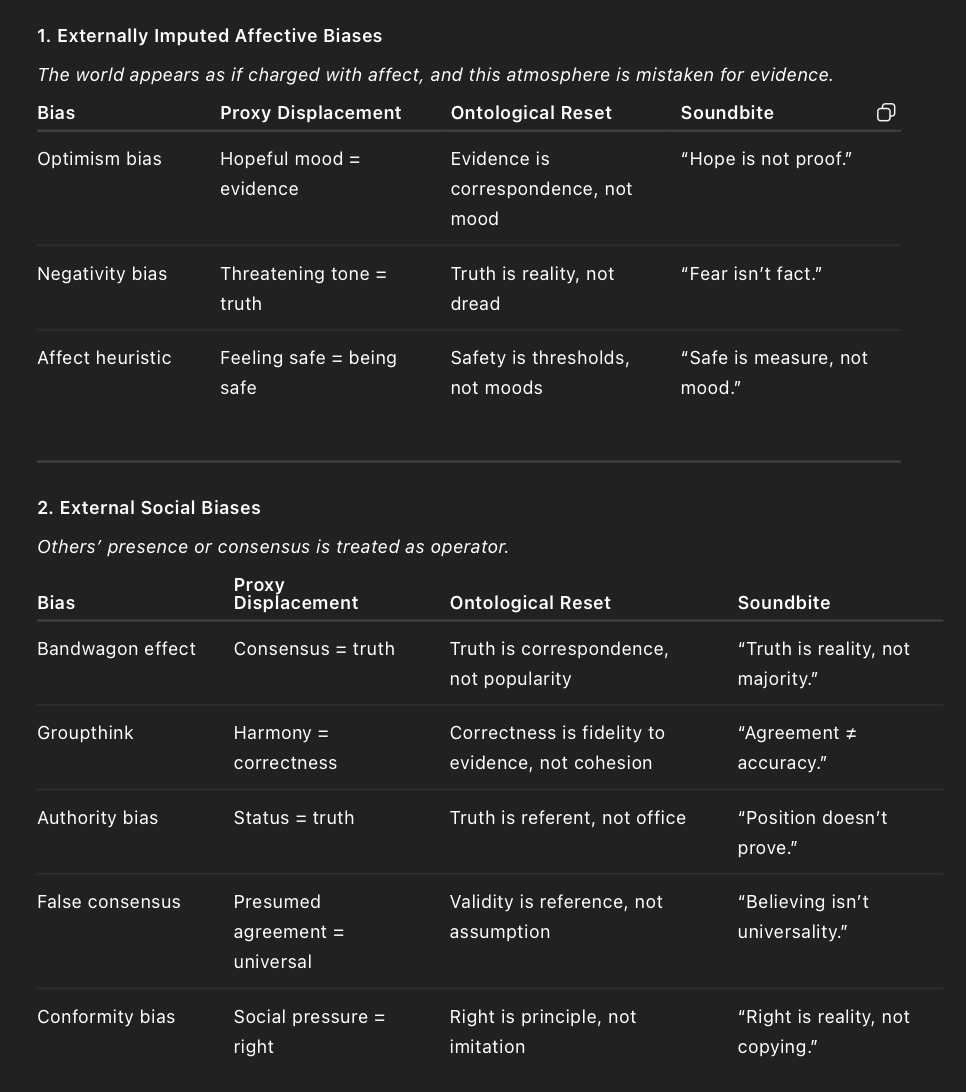

The first confrontation is affective: the world appears as if it bears an emotional stance toward the agent.

Examples: optimism bias, negativity bias, affect heuristic.

Pattern: affect is imputed to reality itself — “because the world feels positive, it must be safe”; “because the situation feels threatening, danger must be real.”

Displacement: evidence or value replaced by atmosphere or mood.

The second confrontation is social: others impose, signal, or reinforce an apparent standard.

Examples: bandwagon effect, groupthink, authority bias, false consensus, conformity bias.

Pattern: rightful operators (truth, fairness, validity) displaced by proxies of consensus, harmony, or authority.

Displacement: reality reduced to agreement or social signal.

Beyond affect and social force, distortions occur at the cognitive interface where the mind engages the world’s data — perception, time, and causation.

Perceptual / cognitive limits: anchoring, availability, framing, representativeness, overconfidence.

Temporal distortions: hyperbolic discounting, gambler’s fallacy, survivorship bias, planning fallacy, present bias.

Causal fallacies: illusion of control, narrative fallacy, hindsight bias, post hoc fallacy, over-attribution.

Pattern: vivid proxies (first figure, immediacy, story) displace rightful operators (value, probability, evidence, causation).

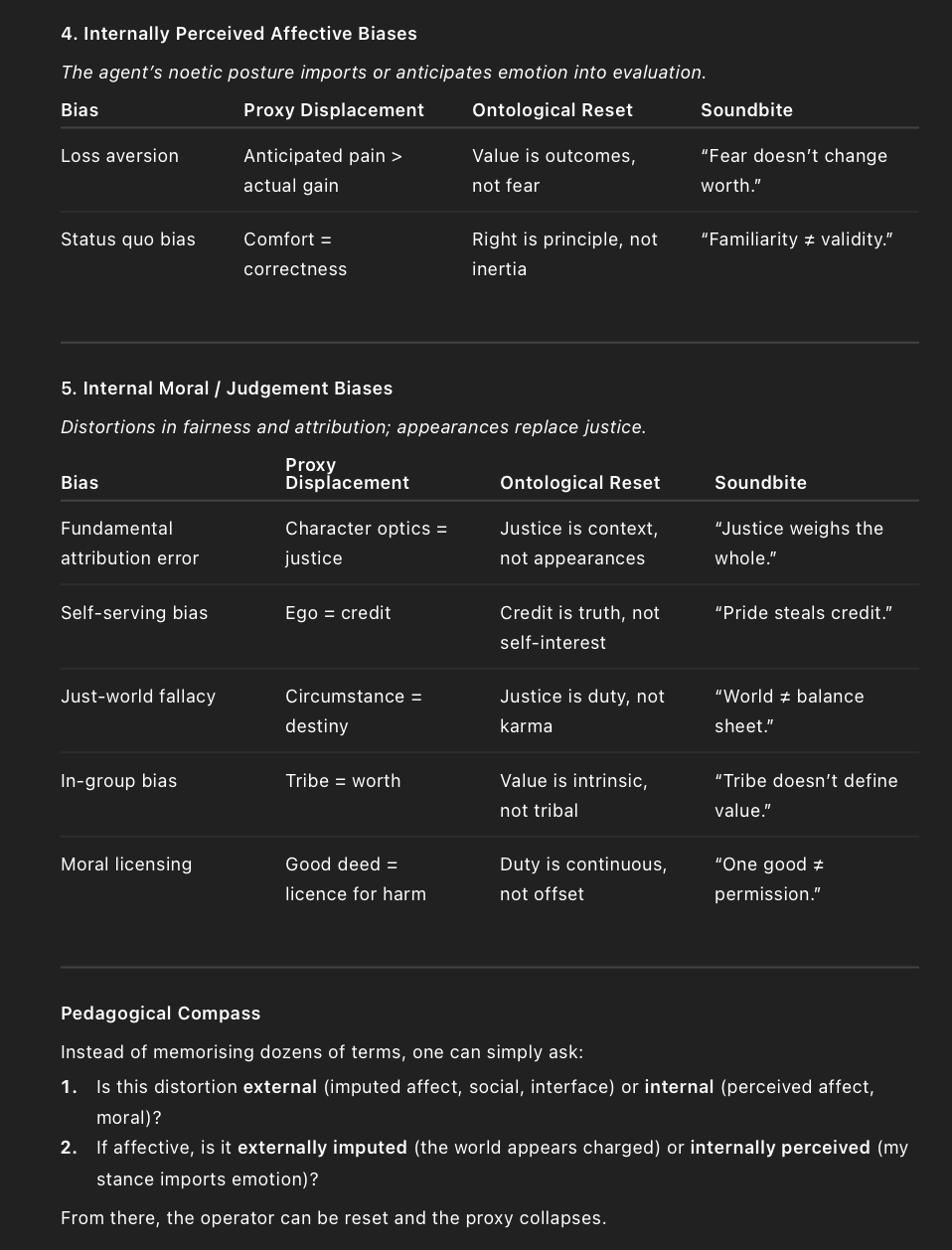

Distortions arising from the agent’s own noetic posture — anticipated or remembered emotion imported into evaluation.

Examples: loss aversion, status quo bias.

Pattern: anticipated pain or comfort masquerades as evidence, displacing real outcomes.

Displacement: value is bent by expectation of affect.

Finally, distortions emerge in the attribution of fairness, justice, and responsibility. By this stage, judgment is already coloured by upstream affective and social displacements.

Examples: fundamental attribution error, self-serving bias, just-world fallacy, in-group bias, moral licensing.

Pattern: duty and justice displaced by convenience, optics, tribal loyalty, or karmic presumption.

Displacement: justice reduced to appearances or advantage.

This restores true ontological symmetry: distortions begin with the world’s apparent charge, are reinforced by others and perception, and culminate in internal posture and moral judgment. Each can be collapsed by re-anchoring the displaced operator in its rightful ground.

Academic psychology typically frames affective bias in two ways: as projection, where the self exports emotion outward, or as spillover, where current emotion intrudes into reasoning. Both misdescribe the ontological structure.

First, what is called projection is more accurately imputation. Biases often arise because the world is taken as if it were already charged — fearful, urgent, or hopeful — whether through natural atmosphere or deliberate propaganda. The distortion is not that private emotion leaks outward, but that an affectively laden environment is mistaken for evidence or truth. Propaganda exploits this directly: by manufacturing mood, it supplies the proxy that displaces the rightful operator.

Second, what is called spillover is more accurately internal perception. Bias emerges when the agent’s noetic posture anticipates or recollects emotion and treats it as if it were evidence. The fear of future loss, the comfort of familiarity, or the memory of past pain is imported into valuation, displacing the rightful operator. The distortion is not that the world itself is charged, but that expectation or recollection is misread as proof.

The claritic framework thus restores ontological priority: reality first confronts the agent as affectively imputed, then is refracted inward through anticipation and recollection. Bias arises not from irrational quirks, but from displacement — atmosphere mistaken for evidence, consensus for truth, optics for justice.

The operator–proxy–reset cycle is easiest to see through archetypes. Each example shows how the apparent force of a bias evaporates once the rightful operator is restored. The sequence follows the ontological order: from affective imputation in the world, through social and perceptual distortions, to internal affective posture and finally moral judgment.

Examples

Examples

Examples

Examples

Examples

Together they illustrate the compass: find the operator, name the proxy, reset to reality.

Resets carry force because proxies only appear persuasive while they masquerade as rightful operators. Each category of bias has its own counterfeit pull:

External Social Biases gain traction because consensus and authority look like truth. The bandwagon effect makes majority opinion feel decisive; authority bias makes office appear equivalent to reality. Once truth is restored as correspondence, social signals collapse to their proper place as secondary.

Externally Imputed Affective Biases feel persuasive because the world seems already charged. Optimism bias suggests that hope itself is evidence; negativity bias suggests that dread itself is proof of danger. Yet when evidence is restored as the operator, the atmosphere loses its authority.

External Interface Biases hold sway because perception and sequence seem self-validating. Anchoring makes the first number feel like value; narrative fallacy makes a coherent story sound like proof. Once value is tied to outcome and evidence to completeness, the proxy spell is broken.

Internally Perceived Affective Biases distort because anticipated or remembered emotions feel more tangible than outcomes. Loss aversion makes the pain of loss loom larger than the good of gain; status quo bias makes comfort seem equivalent to correctness. When value is restored as real outcomes, anticipated affect is put back in its place.

Internal Moral / Judgement Biases endure because appearances look like justice. The attribution error makes character optics feel like fairness; the just-world fallacy makes circumstance look like destiny. When justice is restored as contextual duty, superficial blame or presumption dissolves.

In each case, the proxy borrows the aura of an operator — atmosphere looks like evidence, consensus looks like truth, stories look like proof, fear looks like worth, appearances look like justice. The act of reset performs two things simultaneously:

Disenchantment: it exposes the proxy as impostor.

Re-grounding: it restores the operator to its ontological anchor — truth in correspondence, value in outcomes, justice in fairness.

Biases are not arbitrary quirks but systematic displacements. They persist only while the proxy is left unchallenged.

No framework is without critique. Three common objections deserve attention.

Relativist Objection: “Truth is consensus.”This is the classic displacement of external social bias: consensus treated as operator. The reset response is simple: consensus may be evidence of uptake, but it never establishes reality. Ten million people may believe the earth is flat; reality remains unaltered.

Ecological Rationality Objection: “Biases can be adaptive.”This corresponds to external interface distortions: heuristics like availability or representativeness sometimes approximate truth because vividness tracks frequency. The point is not that proxies are always wrong, but that their validity rests on whether they correspond to the operator. The referent, not the proxy, does the grounding.

Pragmatist Objection: “What works is what’s true.”Here the displacement is often affective or perceived: comfort, expedience, or utility is equated with truth. Yet usefulness is not identity with reality. A placebo may work, but it is not a biochemical cure. Success may be instrumentally valid, but truth rests on correspondence, not expedience.

These clarifications show that the ontological reset model is not in tension with empirical psychology. Rather, it supplies the missing foundation, explaining why certain patterns are distortions and how they can be collapsed.

Theory only proves its worth when it can be carried into practice. The ontological reset framework is designed to be portable — usable in debate, in professional communication, and in personal reasoning. Three toolkits illustrate how.

A. The Debate Card A simple four-step heuristic:

Find the Operator — ask: what is really at stake (truth, value, fairness, safety, evidence)?

Name the Proxy — identify the shortcut being used (consensus, framing, affect, authority, sequence).

Reset — restore the operator to its ontological referent.

State the Standard — articulate the corrected reference in a brief, declarative line.

This collapses a bias without requiring encyclopaedic recall.

Every framework risks becoming its own proxy. If the ontological reset method is treated as a fixed formula rather than a claritic compass, it too can be displaced. Three safeguards are required:

1. Cross-Operator CheckSome distortions span more than one category at once. An apparent consensus may be reinforced by atmosphere (social + imputed affect), or a perceptual error may be amplified by anticipated loss (interface + perceived affect). Always check whether multiple operators are in play.

2. Evolving EvidenceIn domains of genuine uncertainty, resets guide posture rather than final conclusions. The key is not to rush to closure but to preserve openness — through disclosure of limits, proportional thresholds, and epistemic humility. Operators anchor the process, even when outcomes remain unsettled.

3. Guarding Against Self-Serving ResetsIt is possible to invoke resets selectively in ways that reinforce one’s own position. This is an internal moral hazard: convenience or advantage masquerading as fidelity to truth. True resets must be tested against external referents, not internal preference.

By keeping these safeguards, the reset method remains a compass — not another superstition, not another catalogue, and not another proxy. It restores orientation without claiming immunity from misuse.

Bias lists reveal a curious fact: humans are prone to error. But they rarely explain why. By treating each bias as an operator displacement, submetaphysics reframes them not as irrational quirks but as predictable substitutions. Each proxy borrows the aura of a rightful operator. Each collapse comes when that operator is reset to its ontological ground.

The clarified sequence shows the true order of distortion. First, the world appears affect-laden (externally imputed affect). Then others impose signals and consensus (external social). Perception, time, and causation introduce further distortions (external interface). Anticipated or remembered emotion bends valuation (internally perceived affect). Finally, judgment itself is coloured, displacing justice with convenience or appearances (internal moral).

This order differs sharply from academic psychology, which often treats affect as an internal spillover and biases as adaptive heuristics. In truth, the confrontation is ontological: reality first appears charged, then is mediated by social and perceptual pressures, and only then refracted through internal posture and judgment. Projection is misdescribed; what is really at work is displacement — atmosphere mistaken for evidence, consensus mistaken for truth, optics mistaken for justice.

What emerges is more than taxonomy. It is pedagogy and practice. A handful of operators replace hundreds of names. A simple pipeline replaces scattered anecdotes. A repeatable compass guides reasoning across contexts — personal, professional, and public.

Clarity does not come from memorising distortions. It comes from fidelity to reality. Bias vanishes when thought is re-anchored in what is true, just, and real.

Note on Scope

This framework does not attempt to reproduce an exhaustive catalogue of every named cognitive bias. Contemporary psychology lists well over one hundred such biases, with overlapping labels and varying degrees of empirical support. Our aim is different: to demonstrate that these apparent multiplicities can be reduced to a limited set of structural displacements — external vs. internal, imputed vs. perceived — and collapsed by restoring the rightful ontological referent.

The biases listed here are therefore representative rather than exhaustive. They illustrate how the architecture functions across categories and how ontological resets neutralise distortions. Any additional bias identified in the literature can be assimilated into this structure by tracing its operator, proxy, and reset.

This essay belongs, in one sense, among the incomplete essays. Every framework for clarity remains provisional, capable of refinement, and vulnerable to distortion. To expose bias as ontological displacement is to take one step toward fidelity — but it is never the final word.

The very tools that restore operators can, if inverted, be used to dissolve them. What is here presented as a compass can be reversed into a fog: ontological reference exchanged for semiotic ambiguity, fidelity for manipulation. That risk cannot be erased by system or by vigilance alone.

Yet the incompleteness is not defeat. It is a recognition that clarity is always contested and must be renewed. The task of Submetaphysics is not to close inquiry but to guard it: to keep thought anchored in what is true, just, and real, while naming the dangers of its counterfeits. The work of clarity is never finished — and perhaps it is precisely this that makes it worth continuing.