The correspondence theory of truth is among the oldest and most widely accepted accounts of what it means for a statement to be true. In its familiar form, it asserts that truth consists in correspondence between thought or language and reality. The formula is often treated as self-evident, requiring little elaboration beyond the assertion that statements are true when they “match” the world.

Yet this apparent simplicity conceals a deeper difficulty. The correspondence formula is typically invoked in a truncated form—truth is that which corresponds—without explicit attention to what is doing the corresponding, what is being corresponded to, or how correspondence itself is to be assessed. These omissions are not merely stylistic. They mask substantive commitments about correctness, error, and the standards by which representation is judged.

This essay argues that the correspondence theory is only coherent when these suppressed commitments are made explicit. In particular, it contends that correspondence presupposes an external standard of correctness that is not generated by language, propositions, or internal coherence alone. Without such a standard, the very notions of error, misrepresentation, and correction lose their force, and truth collapses into procedure or convention.

The requirement that truth have an external reference is most starkly visible in law, where statements function as propositions that stand or fall by verification against evidence independent of the claim itself, rather than by coherence, consensus, or narrative plausibility.

The aim here is not to introduce a novel theory of truth, but to restore the correspondence theory to its minimally complete form. By carefully distinguishing between objects, propositions, and truth, and by examining how correctness functions in both empirical and abstract domains, the essay seeks to show that truth cannot be secured from within language itself. If truth is real, it must be answerable to what constrains representation rather than what merely organises it.

Truth, meaning, and correctness are not generated internally by language, propositions, or systems of representation. A proposition is truth-apt only insofar as its correctness is answerable to a standard not constituted by the proposition itself, nor by the coherence, consensus, or procedural validity of the system in which it appears. Where no such external standard exists, error becomes unintelligible, correction collapses into convention, and truth reduces to endorsement. The ENP names this constraint explicitly: normativity is external to representation and cannot be produced by it.

The correspondence theory is most often stated in a compressed formula: truth is that which corresponds. While rhetorically efficient, this formulation is structurally incomplete. The verb corresponds is left underspecified, concealing the conditions under which correspondence can be meaningfully evaluated.

When expanded to its minimally coherent form, the claim is not simply that “truth corresponds,” but that a proposition corresponds to an object, and does so correctly by reference to a standard not generated by the proposition itself. This expansion does not add content to the theory; it restores what the theory already presupposes. Without it, correspondence lacks criteria, and the distinction between success and failure becomes unintelligible.

The persistence of the truncated formula is historically understandable. In contexts where a shared metaphysical order, stable objects, and non-arbitrary standards of correctness were tacitly assumed, the ellipsis caused little trouble. In contemporary discourse, however, where such assumptions are often questioned or denied, the omission becomes destabilising. Error, disagreement, and correction cannot be explained unless correspondence is answerable to something beyond the linguistic act itself.

The task, then, is not to revise the correspondence theory, but to complete it—to make explicit the external reference points it already relies upon but rarely names.

Any attempt to clarify correspondence without circularity requires strict separation of levels that are commonly conflated. Three such levels are essential.

First, there is the object, understood ontologically. An object is a reality that exists independently of representation and constrains how it may be represented. Objects are neither true nor false. They do not evaluate propositions, nor are they evaluated by them. Their role is regulative rather than semantic: they permit some descriptions and resist others by virtue of what they are.

Second, there is the proposition or statement, understood semantically. A proposition is a nominative articulation of a relationship, typically expressed in language or thought. Propositions are truth-apt: they can succeed or fail. However, nothing internal to a proposition secures its correctness. Its success depends entirely on how it stands relative to what it purports to represent.

Third, there is truth, which must itself be carefully disambiguated. In one sense, truth appears as a truth-predicate—the linguistic act of marking a proposition as correct (“this statement is true”). In a deeper sense, truth refers to the standard of correctness that makes such marking non-arbitrary. This latter sense does not name a new entity; it names the authority of what is over how it is represented. Confusing these two senses leads either to subjectivism (truth as endorsement) or to nominalism (truth as a label).

The governing principle that follows is straightforward: objects constrain representation; propositions attempt representation; truth-predication marks success; and standards of correctness ground the legitimacy of that marking.

If truth involves correctness rather than mere agreement, then the standards by which correctness is judged cannot be generated internally by the systems they evaluate. A standard cannot justify itself without circularity. Language cannot certify its own adequacy, and coherence alone cannot distinguish truth from error.

If correctness were internally constituted, then consensus, procedural validity, or formal consistency would suffice to establish truth. Yet these criteria fail to account for robust error. Disagreement would reduce to divergence in practice, correction to re-training, and misrepresentation to deviation from convention. The fact that we treat some representations as wrong regardless of consensus indicates that correctness is not a function of internal organisation alone.

Standards of correctness must therefore be externally answerable. This externality does not imply empirical objects in every case, but it does require reference to something not generated by the representational act itself. To deny this is to render error unintelligible and truth vacuous.

Where correctness is real—where representation can succeed or fail in a way that matters—it must be grounded in what constrains representation rather than in representation itself.

If correspondence is to be more than a metaphor, the object must be understood as playing an active role in the success or failure of representation. Objects# are not passive recipients of description, nor are they neutral substrates awaiting linguistic imposition. An object, in the relevant sense, is that which constrains representation. It permits some characterisations and resists others, not by convention or agreement, but by virtue of what it is.

This constraint is often invisible when representation succeeds. When a proposition aligns with the object, there is little to notice; the object does not announce its compliance. It is in cases of strain—misclassification, error, or overextension—that the object’s constraining role becomes apparent. In resisting inaccurate representation, the object reveals that it is not constituted by the act of description, but stands independently of it.

The possibility of misrepresentation is therefore not a defect of correspondence, but a condition of its intelligibility. If objects did not constrain representation, failure would be indistinguishable from difference, and correction would lose its point. Correspondence is thus not a symmetry between language and world, but a one-sided accountability of propositions to what limits them.

The distinction between accuracy and precision clarifies how objects exert this constraint. Precision concerns the internal organisation of a representational system. It is model-relative, internally referenced, and often cumulative. A representation may become increasingly precise—more detailed, more formally consistent—without becoming more accurate.

Accuracy, by contrast, is externally referenced. A representation is accurate insofar as it aligns with what the object will tolerate. This alignment is not revealed by internal refinement alone, but by confrontation with constraint. Accuracy is therefore most clearly disclosed at boundaries: where predictions fail, classifications break down, or models encounter resistance.

This explains why epistemic progress often occurs through failure rather than refinement. Precision can mask misalignment by increasing internal coherence, while accuracy cannot be secured without reference to what lies outside the representational system. Objects enforce accuracy; they are indifferent to precision.

Understanding correspondence in these terms prevents a common confusion. Correspondence is not achieved by ever-greater internal articulation, but by satisfying external correctness-conditions. The object does not reward elegance or consistency; it permits or refuses.

When correspondence succeeds, language often appears trivial. Consider the statement: “The glass I am staring at is a glass.” At first glance, this may seem tautological, even empty. Yet this appearance is misleading. The statement is not a logical tautology of the form A = A. Rather, it is a classificatory redundancy that becomes trivial only after successful external reference has already occurred.

The sentence presupposes that the object in question has been correctly identified as a glass—that it satisfies the criteria governing that classification. The standards of correctness have already been met, but they are no longer visible in the statement itself. What remains is linguistic residue: a redundancy that signals success, not necessity.

This explains why correct empirical statements often feel obvious, while incorrect ones demand explanation. When alignment holds, language goes quiet; when it fails, language becomes noisy. Triviality is therefore not evidence of internal self-validation, but of prior correctness satisfied externally.

The statement is not true because it is redundant; it appears redundant because it is true. This analysis generalises beyond the example: declarative statements often appear tautological precisely when external correctness has already been satisfied, not because truth is internally generated, but because successful reference collapses linguistic tension. Correctness precedes linguistic simplicity, and the simplicity is a consequence of alignment, not its cause.

Having established that correctness cannot be generated internally by propositions or representational systems, it is now possible to address truth itself without collapsing it into endorsement or procedure. When a proposition is said to be true, what is being expressed is not the creation of a new status, but the recognition of successful alignment with the standards of correctness imposed by what constrains representation.

Truth, in this sense, does not depend on recognition in order to hold. A proposition may be true without being known, affirmed, or even entertained. Recognition is an epistemic relation to truth, not its condition of existence. To conflate the two is to mistake the act of judging for the ground of judgment.

This distinction preserves objectivity without reifying truth as an entity. Truth is not a thing added to propositions, nor a property they acquire by consensus. It names the condition under which a proposition stands correctly related to what it represents. Truth-predication is a linguistic act; the correctness it marks is not linguistic. Evaluation is answerable to correctness; correctness is not generated by evaluation.

Understanding truth in this way avoids two common errors. It avoids subjectivism, by refusing to locate truth in acts of assent. And it avoids nominalism, by refusing to treat truth as a mere label applied to favoured propositions. Truth holds independently; recognition discloses rather than produces it.

It might be objected that the foregoing account applies only to empirical statements, where external objects obviously constrain representation. Mathematical statements, by contrast, appear to be internally grounded. Identities such as 2 = 2seem to require no appeal beyond the formal system in which they are derived. This appearance, however, rests on an equivocation between formal derivability and correctness of use.

Within a formal system, a theorem may indeed be derivable from axioms by stipulated rules. Yet the meaningful use of that theorem presupposes more than derivability. It presupposes shared symbols, stable identity conditions, and non-arbitrary inferential norms. These are not generated by the individual statement, nor by the act of proof itself. Proof is internal; the correctness of meaning is not.

This is why mathematical disagreement is intelligible and corrigible. If correctness were exhausted by internal derivation, error would be indistinguishable from alternative stipulation. The fact that mathematical claims compel assent rather than invite persuasion indicates that they are answerable to an abstract structure that is presupposed, not constructed ad hoc.

Thus, mathematical truth is not empirically external, but it is not normatively internal either. It depends on shared, rule-governed reference and stable standards of correctness that make common understanding possible. The domain differs from the empirical case, but the structure is the same: no statement grounds its own correctness.

Once correctness is acknowledged as externally answerable, a further question becomes unavoidable: how far does this answerability extend? If standards of correctness themselves require grounding, an infinite regress threatens to dissolve their authority. A standard that is always provisional cannot finally bind.

There are, in principle, three ways such a regress might terminate. The first is not to terminate it at all. Infinite regress, however, undermines correctness by deferring it indefinitely; nothing is ever finally settled. The second is to impose a brute stopping point—an arbitrary foundation declared sufficient without explanation. This secures finality at the cost of non-arbitrariness. What is simply stipulated cannot bind as correct.

The third option is a non-derivative ground: a source of constraint that does not itself derive its authority from something else. Such a ground may be necessary rather than contingent; what matters is that it is not arbitrary. Only this option preserves correctness as something that can genuinely govern representation rather than merely organise it.

This conclusion is not introduced for theological reasons, nor does it depend on any particular doctrinal commitments. It follows from a refusal to accept circularity or arbitrariness in the account of truth. If correctness is real—if error is meaningful and correction binding—then grounding must terminate in something that constrains without itself being constrained in the same way.

Classical philosophy names such a terminus aseity or First Cause, but the terminology is secondary. What matters is the function: a non-derivative source of constraint without which truth loses determinate force and correspondence collapses into procedure.

When the correspondence theory of truth is stated without ellipsis, its commitments become clear. It does not merely claim that statements relate to the world in some loose or metaphorical sense. It claims that propositions succeed or fail relative to what constrains them, and that truth names the condition under which such success holds. To accept correspondence, therefore, is already to accept standards of correctness that are not generated by language itself.

Maintaining the distinction between object, proposition, and truth is essential. Objects are not truth-bearers; they impose limits. Propositions are truth-apt but not self-validating; they articulate relationships that may or may not align with what they purport to represent. Truth-predication is a linguistic act that marks success, while the correctness it marks is grounded in what resists misrepresentation. Confusing these levels leads either to circularity or to the evacuation of truth into convention.

This structure explains several otherwise puzzling features of our epistemic practice. It explains why precision alone cannot secure correctness, why failure and boundary conditions are epistemically revealing, and why correct statements often appear trivial only after alignment has been achieved. It also explains why abstract domains such as mathematics, despite their formal character, still presuppose shared reference and non-arbitrary standards of correctness. No statement—empirical or abstract—grounds its own validity.

If correctness is real, then it cannot regress indefinitely or rest on arbitrary stipulation. A standard that is endlessly deferred cannot finally bind; a standard that is merely declared cannot compel. External answerability therefore requires termination in a non-derivative ground—something that constrains representation without itself borrowing that constraining authority from elsewhere. This conclusion is not introduced by metaphysical enthusiasm, but by epistemic integrity: a refusal to accept circularity or arbitrariness in the account of truth.

The correspondence theory, properly understood, does not collapse into linguistic self-reference, nor does it float free of grounding. It stands or falls with the reality of external correctness-conditions. Restoring its suppressed commitments does not inflate the theory; it stabilises it. What emerges is not a novel doctrine, but a clarified accounting: truth is the recognition of correct alignment, where correctness is answerable to what is, and intelligible only because constraint ultimately holds.

Footnotes

Historical Orientation — What Was Assumed, Asserted, and Contained

The argument developed in this essay does not arise in a historical vacuum. Questions concerning truth, correspondence, and grounding have been addressed—often with great sophistication—by earlier thinkers. It is therefore important to clarify how the present account relates to several canonical positions, and in particular what those figures did and did not explicitly establish.

Aristotle

For Aristotle, truth is fundamentally tied to being. His well-known formulation—that to say of what is that it is, and of what is not that it is not, is true—presupposes an ordered reality in which form, substance, and final cause are intelligible. Objects have determinate natures, and reason is naturally oriented toward grasping them. In this context, correspondence does not require extensive justification; the world is already assumed to be normatively authoritative.

What Aristotle does not do, however, is reflexively interrogate the epistemic necessity of this authority. He assumes that being constrains thought, but he does not ask what would become of truth if such constraint were denied or rendered inaccessible. Nor does he derive the grounding of truth as a condition of intelligibility for error, correction, and common reference. His metaphysical conclusions are robust, but the dependency of truth itself on non-derivative grounding remains largely implicit.

Thomas Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas brings greater explicitness to the relationship between truth and being. For Aquinas, truth follows being (verum sequitur esse), and God, as ipsum esse subsistens, is the ultimate measure of all truth. In this sense, Aquinas clearly affirms what the present essay concludes: that truth is grounded in non-derivative reality rather than in linguistic or cognitive structures.

What Aquinas does not fully pursue, however, is the epistemic inevitability of this grounding. He asserts the conclusion largely within a theological-metaphysical framework, supported by revelation and classical metaphysics, rather than demonstrating that the denial of such grounding collapses the very notion of correctness. The grounding of truth is affirmed, but not derived as an unavoidable consequence of taking error and correspondence seriously.

Immanuel Kant

The contrast with Immanuel Kant is instructive. Kant is acutely aware of the dangers of grounding logic and truth directly in being. His critical project seeks to secure the universality and necessity of logical principles by locating them in the conditions of possible experience rather than in things as they are in themselves. In doing so, Kant preserves logical form and epistemic necessity while deliberately bracketing ontological grounding.

This move is not a failure of insight but a principled containment. Kant recognises that allowing truth and logic to answer directly to being risks metaphysics, and metaphysics risks theology. The cost of this containment, however, is that normativity becomes internal to cognition. Correctness is secured procedurally, but its authority over reality is no longer established. Truth remains necessary for us, but its binding force is no longer grounded in what is.

Popper and the Limits of Falsifiability

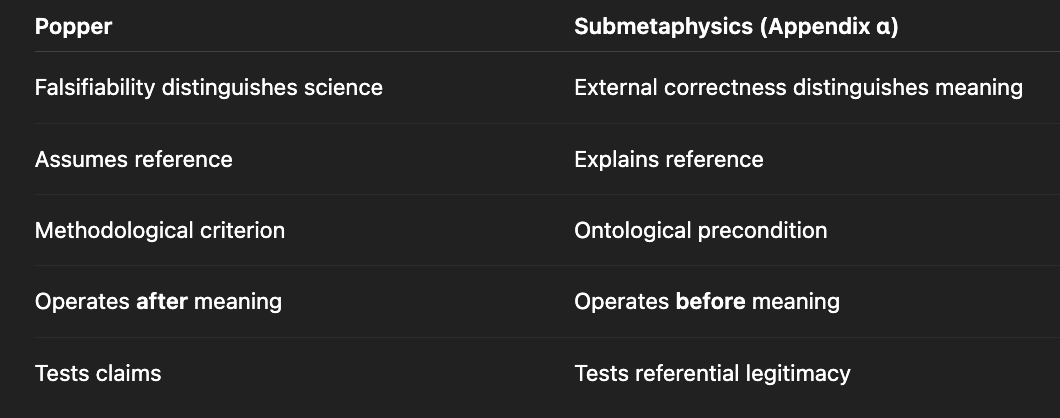

Karl Popper’s falsifiability criterion is often taken to secure realism by distinguishing meaningful scientific claims from unfalsifiable ones. However, falsifiability operates at a methodological rather than ontological level. It presupposes that propositions already possess determinate reference, that error is intelligible, and that reality can in principle resist representation. What it does not address is what makes such resistance possible in the first place.

The present account therefore does not compete with falsifiability, but situates it. Falsifiability presupposes external correctness-conditions; it does not ground them. A claim can only be falsified if it is already answerable to what constrains it rather than to what merely organises it. The External Normativity Principle (ENP) names this precondition explicitly. Without it, falsifiability collapses into procedural coherence, and error becomes a feature of systems rather than a relation to what is.

Falsifiability presupposes external correctness; it cannot ground it.

Falsifiability presupposes external correctness; it cannot ground it.

Position of the Present Argument

The present account differs from all three approaches, not by rejecting their insights, but by making explicit what each leaves implicit or unfinished. Aristotle assumes ontological authority, Aquinas asserts it theologically, and Kant contains it epistemically. What this essay attempts is to show that once correctness, error, and common reference are taken seriously at all, ontological grounding is not optional.In this sense, the argument does not innovate by adding a new doctrine of truth. It clarifies the cost of denial. It shows that truth cannot function—cannot even be intelligible—unless standards of correctness are externally grounded, and that such grounding cannot regress indefinitely or rest on arbitrary stipulation. The appeal to non-derivative constraint is therefore not an historical preference, but the endpoint of epistemic integrity.

Earlier stages of this inquiry were informed by analogies drawn from information theory, particularly in relation to the distinction between signal and noise. Although such frameworks are neutral with respect to meaning and truth, they proved heuristically useful in clarifying how structure becomes detectable relative to background variability.

A signal, in this context, is not defined by sheer difference, but by structured difference. For a signal to be detectable, there must be some form of pattern persistence—typically involving repetition, regularity, or invariant relations—that distinguishes it from stochastic variation. Pure uniformity contains no signal, as there is no contrast to detect; pure noise likewise contains no signal, as there is no stable structure to track. Detectability arises only where organized variationpersists against a background of disorder.

Boundaries, therefore, are not arbitrary demarcations but regions where a pattern maintains identity under perturbation. A boundary is disclosed when an attempted assimilation fails—when the pattern ceases to hold beyond a certain tolerance. In this sense, boundaries are epistemically privileged: they reveal what a system is by showing where it cannot remain itself.

This insight helped motivate a distinction developed later in the essay between cataphytic and anaphytic modes of knowing. Cataphytic knowing operates internally: it refines representations, increases resolution, and enhances precision within a given model. Anaphytic knowing, by contrast, is externally disclosed: it is revealed when representations encounter constraint, resistance, or breakdown. Boundaries, failures, and mismatches are therefore not epistemic defects, but primary sites of disclosure.

The present essay does not ground truth, meaning, or normativity in information-theoretic terms, nor does it derive correctness from entropy, probability, or signal-processing models. The signal–noise framework functions solely as conceptual scaffolding, assisting in the transition from early intuitions about detectability and boundary formation to a fully ontological account of objecthood, correspondence, and externally grounded correctness.

Archival Note: Early Heuristics on Signal, Noise, and Boundary Disclosure