Faith has been downgraded. In modern discourse, it is rarely treated as covenantal. Instead, it is variously reduced to blind devotion, an emotional safety-blanket, a badge of heritage, or an existential gamble. Even within the church, it is typically framed in epistemic terms—belief on the basis of evidence, confidence in the unseen—as though faith were chiefly a product of human judgment, sentiment, or volition. Each of these renderings is thin. They begin with the subject, treat faith as self-generated, and obscure its true foundation.

This appendix offers a reclassification. Within the relational–ontological architecture developed throughout this project, faith is not first an epistemic act but an ontological submission: the soul’s morally accountable “Yes” to a confronting God. It is not projected from within, but provoked from without—a response to being personally and covenantally addressed by the Revealer. Faith is not a rational deduction or a heroic leap into the unknown. It is the recognition that only the Speaker has the right to define reality and summon the creature into alignment. In this light, faith is not a subjective correlation with invisible hope—it is a covenantal conviction born from divine confrontation.

What follows will re-examine faith through this ontological lens, offer a clarified reading of Hebrews 11:1, expose how rebellion imitates but refuses this submission, and show why only the Reformation recovered the covenantal structure that makes faith not only intelligible, but rational and real.

Contemporary portrayals of faith typically presume that the individual must justify it before it can be accepted as rational. This reflects an epistemic captivity that treats the self as the arbiter of truth. Four major distortions follow from this assumption.

First, there is blind faith, often caricatured as believing without evidence. This version of faith is dismissed by critics as irrational, or embraced by some fideists as virtuous—a badge of spiritual courage. But in either case, faith is defined as detached from any ontological grounding and evaluated instead by the will’s audacity to believe.

Second, there is faith with reason—an effort to render belief acceptable through logical argument or philosophical coherence. While appearing more sophisticated, this still rests on the assumption that faith is something the individual must verify, rather than something they are summoned into by divine confrontation.

Third, faith in science is sometimes presented as a superior model of belief. Here, faith is recast as confidence in the predictive power of empirical method. But this, too, misframes faith by placing its ground in observable regularities, thereby limiting reality to the measurable and suppressing the moral.

Fourth, apologetics often attempts to defend the rationality of faith. While valuable within its scope, apologetics becomes misguided when it seeks to establish the legitimacy of faith from human vantage points—treating divine revelation as a hypothesis to be evaluated rather than a summons to be submitted to.

These four models share a common flaw: they relocate the authority of faith from the Revealer to the self. In so doing, they invert the proper ontological sequence. Faith is not made valid by evidence, emotion, logic, or probability. It is made valid by its object—specifically, by the ontological authority of the One who calls.

Faith, in its biblical sense, is neither private sentiment nor calculated inference. It is ontological submission—the soul yielding to God’s intrusive presence. The movement begins not in the seeker but in the Revealer, who engages every person along an epideictic–elentic axis:

Epideictic — God’s self-display that unveils His reality and rightful rule. This is an objective disclosure that removes plausible deniability.

Elentic — The convicting exposure (elegchos) that follows, laying the heart bare and summoning a verdict.

These are not passive events—they create moral obligation. Faith is the relational response that follows this two-edged disclosure: the posture a person assumes when divine glory is presented and their conscience is pierced, compelling them either to align or to resist.

This dynamic has already been traced in the appendix on Paul. Paul on the Damascus road, Nebuchadnezzar in his humiliation, and the Thief beside Christ each illustrate divine intrusion. The Prodigal Son, though parabolic, shows the same pattern: he “comes to himself” only after relational loss and mercy confront him. We also review this topic in depth in the DM unit essay. Such confrontation is universal; no one is judged without first being drawn and summoned. It is a necessary act of divine justice.

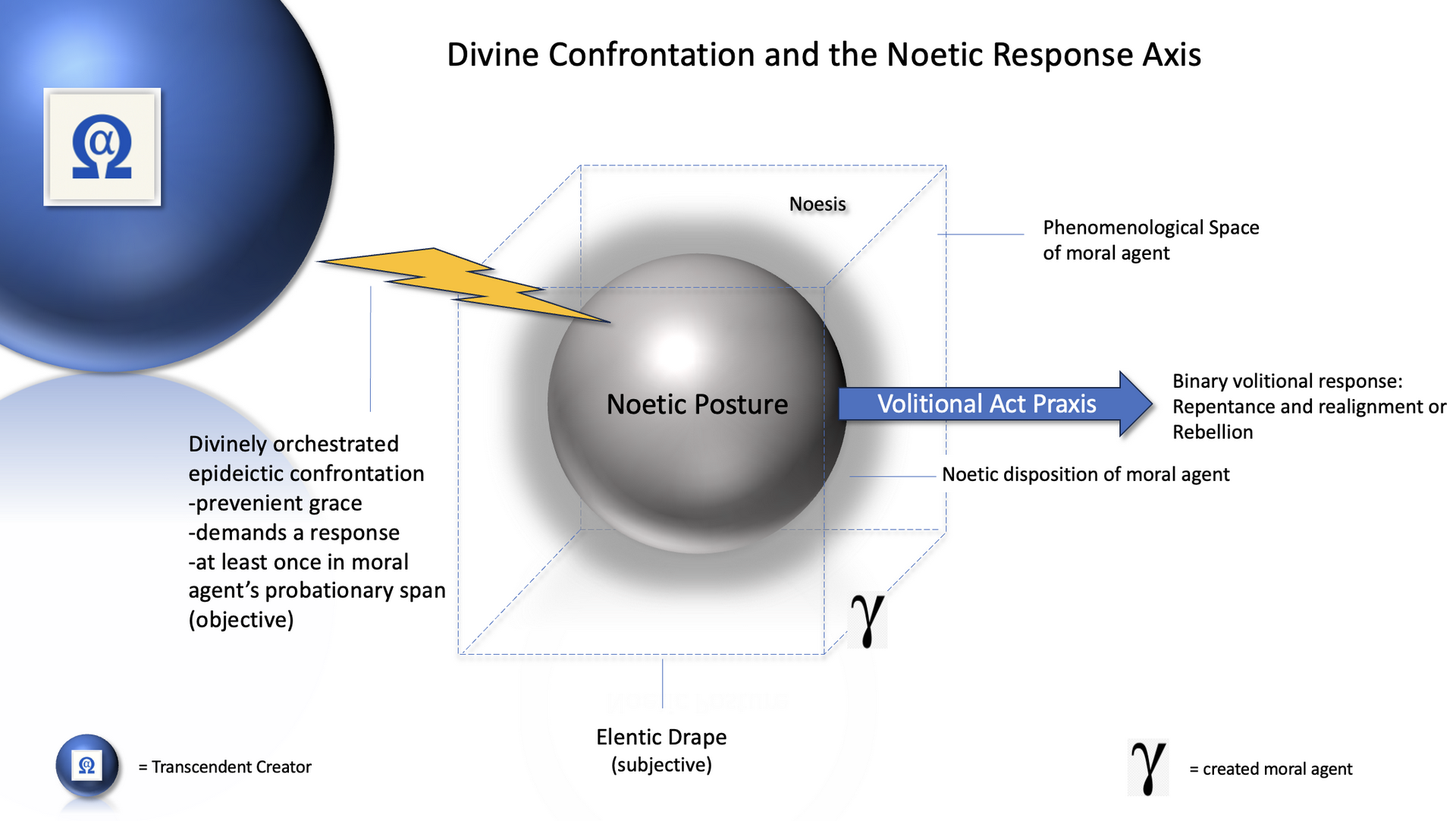

Below we reproduce the diagram from the essay on Moral Taxonomy where this topic is also discussed from a moral perspective.

This diagram depicts the moral drama of a human agent’s encounter with divine truth.

The Transcendent Creator (α—Ω) initiates a divinely orchestrated epideictic confrontation, an act of prevenient grace that occurs at least once during the moral agent’s probationary span. This confrontation is not merely informational but morally invasive—summoning a response from the agent’s inner orientation. The confrontation enters the phenomenological space of the moral agent, represented by the bounded transparent cube.See Moral Taxonomy essay, Section III.E.1 for a detailed legend for this diagram and discussion.

Faith is not a human achievement. It is not the result of intellectual synthesis or emotional resolve. It is a moral response made possible only because the Revealer has acted first. In Scripture, faith is consistently presented not as a native capacity but as a divine gift—originating in God's own confrontation and drawing.

This point is not peripheral; it is structural. The very act of believing presupposes a divine enablement. The agent responds, but only because something prior has occurred: truth has addressed the soul, and grace has made response possible.

This is reinforced across the New Testament:

Ephesians 2:8–9 – “By grace are ye saved through faith; and that not of yourselves: it is the gift of God—not of works, lest any man should boast.”→ Faith itself is part of the gift—not simply the grace that surrounds it, but the very capacity to respond.

Philippians 1:29 – “Unto you it is given on the behalf of Christ… to believe on him.”→ Belief is not merely permitted—it is granted. The verb ἐχαρίσθη (echaristhē) implies gracious bestowal.

Romans 12:3 – “God hath dealt to every man the measure of faith.”→ Faith is apportioned. It is not self-manufactured, but divinely distributed.

John 6:44 – “No man can come to me, except the Father… draw him.”→ Coming to Christ—i.e., the movement of faith—is impossible apart from the divine initiative. This is not external persuasion but internal confrontation.

Hebrews 12:2 – “Looking unto Jesus, the author and finisher of our faith…”→ Christ is not only the goal of faith, but its architect. He initiates and completes it. Galatians 2:20 - crystallises this: “I am crucified with Christ; nevertheless I live; yet not I, but Christ liveth in me: and the life which I now live in the flesh I live by the faith of the Son of God, who loved me, and gave himself for me.” Paul interprets the Christian life as ontological union with Christ, pneumatological indwelling, and lived participation in the Son’s authored fidelity.

Together, these texts reveal a consistent structure: faith is not generated by the agent—it is gifted by the Revealer. It arises downstream from confrontation. The moral agent is responsible for yielding, but even this yielding is only possible because God has first acted.

Christ’s authorship of faith includes the total experiential descent into human frailty and temptation, not its moral concession. He authored fidelity by living it under the full conditions of creaturely vulnerability. His faith was not a demonstration staged for observation but the living enactment of relational trust under concealment—trust maintained when divine presence was hidden and sense afforded no confirmation. In other words: His faith had to operate under the same conditions as ours—no privileged sight, no divine override—only trust.

This authorship was not a simulated ordeal but one laden with cosmic consequence. As the race’s representative, Christ’s fidelity bore corporate soteriological weight: if He had failed in His trust, the Father could not have raised Him, and humanity would have perished in Him. The resurrection was not an intrinsic inevitability of divine essence but a contingent outcome of relational fidelity within divine order. In His humanity, the Son did not know that His sacrifice had been accepted until He returned to the Father and verified it (John 20:17). This moment discloses not ignorance but authentic filial subordination—the Son’s trust resting wholly on the Father’s prerogative. The cross thus exposes the real jeopardy of faith: that redemption itself hinged upon relational obedience, and that the Son’s vindication, and by extension the race’s, depended upon the Father’s acknowledgment of His perfect surrender.**

Gethsemane stands as the apex of this curriculum of temptation and humiliation, orchestrated by the Father as the proving ground of filial trust.Christ’s confession—“My soul is exceeding sorrowful unto death”—was not moral failure but moral transparency, the disclosure of perfect dependence. In that submission He was “made perfect through sufferings,” qualified to be a sympathetic High Priest who can be touched with the feeling of our infirmities (Heb 4:15). His honesty under pressure is the form of holiness by which He enters into solidarity with fallen humanity without sharing its corruption.

**Doctrinal note. If the Son possessed plenary, co-equal auctoritas instantiandi, the resurrection would be intrinsic and non-contingent; no “return to the Father” for verification (John 20:17) would be meaningful. The text therefore denies triune co-equality and affirms distinct ontorelationality under the Father’s unique prerogative. See Appendix A

for a full discussion.

This path carried the real danger of failure in His assumed humanity, yet He never wavered from filial fidelity. Scripture insists this danger was not empty theatre: He was “in all points tempted like as we are” (Heb 4:15), suffering real enticement that could only be resisted through faith. In the wilderness (Matt 4:1–11), at Gethsemane, and at Golgotha, He endured crises of trust where sense and sight collapsed, and faith alone could prevail. The universe itself was watching (1 Cor 4:9), and the faithful who had gone before were not “made perfect without us” (Heb 11:40). Moses, Elijah, and Enoch were secured by promise, yet their hope awaited the consummation of Christ’s victory. In that hour, “a great cloud of witnesses” (Heb 12:1) encircled the Author and Finisher of faith, beholding whether filial fidelity would endure. It did. Only having authored faith in this way could He impart that fidelity to us and succour us in our weakness (Heb 2:17–18).

Paul captures this reality in Galatians 2:20: “I am crucified with Christ; nevertheless I live; yet not I, but Christ liveth in me: and the life which I now live in the flesh I live by the faith of the Son of God, who loved me, and gave himself for me.” For Paul, life is ontological union, pneumatological indwelling, and lived participation in the Son’s authored fidelity.

This deep dependency—faith as a response to divine initiative—raises a natural question when we arrive at Hebrews 11:1. The verse reads as if faith is producing certainty or providing evidence: “Now faith is the substance of things hoped for, the evidence of things not seen.” At first glance, this seems to suggest a dissonant epistemic construction—faith as something internally generated to bridge an evidential gap. But this would directly contradict the gifted, responsive structure just described. So how should we understand this passage? The next subsection will explore that very question.

The same divine initiative that confronted the Son also confronts every soul. Scripture portrays a spectrum of response: Pharaoh, who hardened his heart; the prodigal, who was broken and returned; and Lydia, whose heart the Lord opened (Acts 16:14).These are not mere historical contrasts but ontological postures toward revelation—resistance, repentance, and receptivity. Christ Himself, in His humanity, embodies the final category: an unbroken openness to the Spirit’s leading, the perfect inverse of Pharaoh’s obstinacy and the consummation of what Lydia’s awakening prefigured. Thus, the faith of Jesus is the archetype of restored relational alignment—the human will perfectly yielded to divine initiative.

“Now faith is the substance of things hoped for, the evidence of things not seen.” (KJV)

The Greek terms here matter deeply.

Substance (hypostasis): The underlying, unseen reality—faith participates in what God has already disclosed. Evidence (elegchos): Not argumentative proof, but moral conviction—faith is the internalized acknowledgment of what has already confronted the soul. This is not the beginning of confrontation, but its inward outworking. Hebrews 11:1 does not depict the elentic moment, but the relational result of having already been confronted.

Paraphrase of Heb 11:1- Faith is the lived certainty of what God has promised, and the God-given conviction that unseen realities are already true.

Lexical Note: Elentic Confrontation in Scripture

Elentic (from Gk. elegchos) means convicting exposure. Most NT uses refer to God's external act of confronting the sinner with truth—demanding moral response. Examples include:

John 16:8 – the Spirit “will convict (elegxei) the world …"

Eph 5:11–13 – believers must “expose (elegchete) …”

2 Tim 3:16 – Scripture is profitable for “reproof (elegchon)”

Titus 1:9; 2:15, Rev 3:19, Matt 18:15, Jude 15

In these cases, elegchos refers to a momentary, often judicial exposure that demands a verdict.

Hebrews 11:1 shifts the direction: it describes the inward result of having been confronted—an ongoing assurance, not an external rebuke. The same root is present, but its function changes. Hence the paraphrase: Faith is the lived certainty of what God has promised, and the God-given conviction that unseen realities are already true.

This makes clear that faith in Hebrews 11:1 is not a leap into the dark, but a conviction grounded in what God has already disclosed. Yet a further problem remains: have our translations preserved this depth, or have they reduced it?

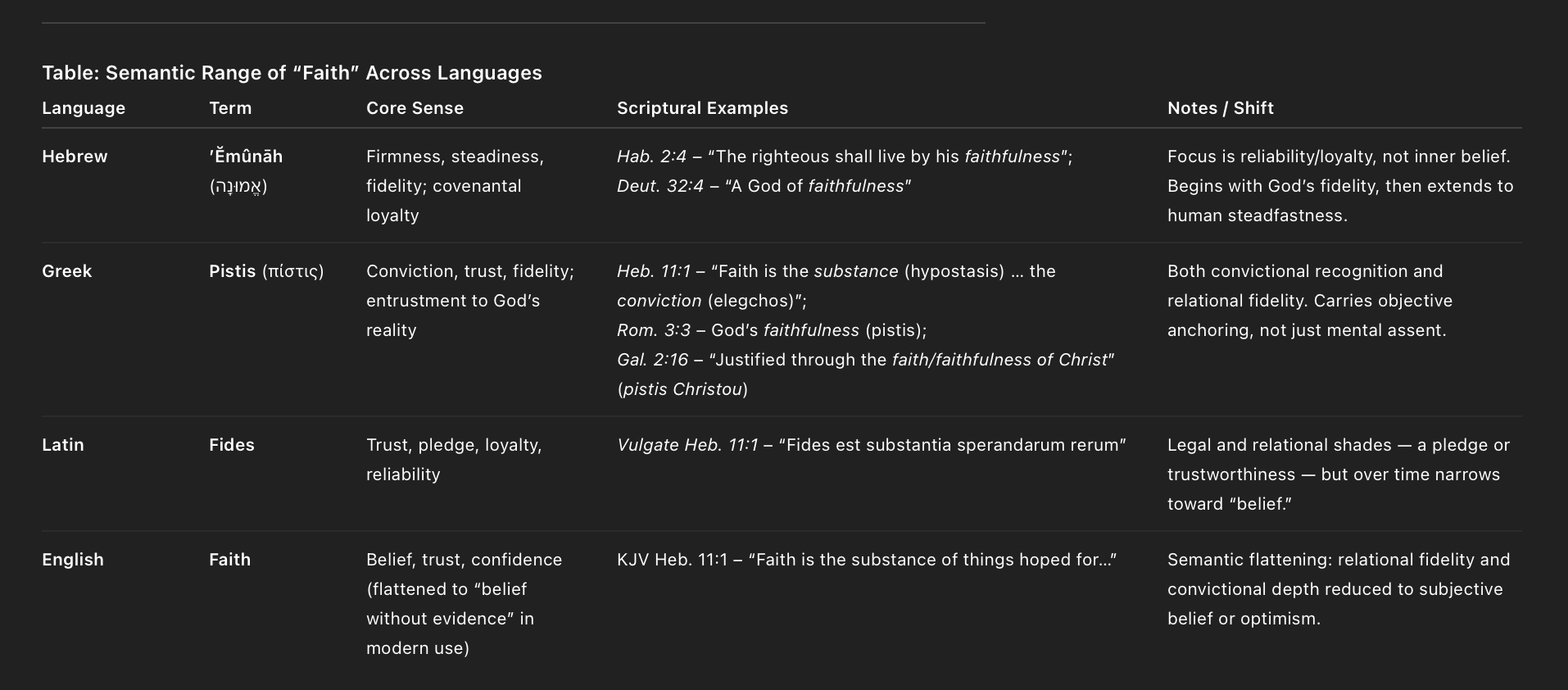

A further complication is that in modern English, the word faith has undergone semantic flattening. It often suggests little more than “belief” or “optimism,” whereas the biblical languages carried deeper layers that distinguish between confrontation, conviction, and sustained fidelity. The translations, particularly in the King James Version, tended to collapse these nuances into a single rendering of faith, obscuring their ontological weight.

Hebrew – ’emunah (אמונה)The Hebrew word ’emunah denotes firmness, steadiness, or fidelity. It is not belief in the abstract, but a lived reliability in response to God’s disclosure. Thus:

Habakkuk 2:4: “The righteous shall live by his faith/faithfulness (’emunah).” Here the sense is not blind optimism but steadfast fidelity under divine confrontation.

Deuteronomy 32:4: “A God of faithfulness (’emunah) and without iniquity, just and upright is he.” Faithfulness first belongs to God, then defines the covenantal response of His people.

Greek – pistis (πίστις)In the New Testament, pistis encompasses both conviction and fidelity. It is relational and covenantal: conviction anchored in God’s action, lived out in loyal entrustment.

Hebrews 11:1: “Now faith (pistis) is the substance (hypostasis) of things hoped for, the conviction (elegchos) of things not seen.” This is not subjective wishing but objective conviction grounded in God’s reality.

Romans 3:3: “What if some were unfaithful? Does their faithlessness (apistia) nullify the faithfulness (pistis) of God? By no means!” Here pistis includes fidelity as much as belief.

The Faith of Christ – pistis ChristouThe debated phrase pistis Christou (e.g., Galatians 2:16; Romans 3:22) is often translated “faith in Christ,” but it may more properly mean “the faith/faithfulness of Christ.”

Galatians 2:16: “A person is not justified by works of the law but through the faith [pistis] of Jesus Christ (pistis Iēsou Christou), so we also have believed in Christ Jesus, in order to be justified by the faith of Christ and not by works of the law.”

Philippians 3:9: Paul longs to “be found in him, not having a righteousness of my own… but that which comes through the faith of Christ, the righteousness from God that depends on faith.”

In these passages, the emphasis falls not merely on the believer’s disposition but on Christ’s own conviction and fidelity toward the Father, into which the believer participates.

Practical Implication: Thus when exhortations today reduce to “have faith,” the practical meaning is easily distorted. What Scripture envisions is closer to: “sustain the conviction already given,” “hold to the fidelity already disclosed,” or “abide in the conviction of Christ Himself.” In lived terms, conviction functions as the experiential register of faith’s ontological gift.

Legend:

This table illustrates the semantic development of faith across languages. In Hebrew (’emunah), the core sense is fidelity and steadfastness. In Greek (pistis), the meaning broadens to include both conviction and relational trust, climaxing in the debated phrase pistis Christou (“faith/faithfulness of Christ”). In Latin (fides), the sense of loyalty and pledge is preserved but begins to tilt toward intellectual assent. In English, “faith” often collapses into subjective belief, losing the ontological and covenantal depth present in the biblical languages.

With this nuance recovered, we can now see that exhortations to “have faith” often obscure the covenantal dynamic. Faith is not mere correlation, but the ratification of God’s confrontation in reality.

Paul’s epistles often compress multiple metaphysical layers into unified theological expressions designed for covenantal confrontation rather than ontological dissection. This compression is not an error, but a mode of divinely inspired rhetorical prioritization—aimed at evoking faith, not diagramming it.

When Paul says, “faith comes by hearing” (Rom. 10:17), or refers to “hearing with faith” (Gal. 3:2), he is invoking a relational summary, not a structural mechanism. He is not claiming that hearing (i.e., sensory exposure to gospel proclamation) is equivalent to ontological reception. Rather, these phrases assume a grace-enabled sequence beneath the language: that prevenient grace orchestrates the occasion, that truth confronts, and that faith may result—but only if the agent surrenders at the point of moral exposure.

This framework disambiguates that sequence with ontological precision. We distinguish:

Hearing as a grace-engineered occasion for exposure, not a form of moral reception;

Prevenient grace as the pre-conditioning of the soul and circumstance, not coercion;

Faith as the agent’s ontological response to a confrontive truth already revealed—never self-generated, never reducible to awareness or assent.

This matters because not all hearing leads to faith, and not all faith arises from hearing. Paul’s own conversion involved no sermon, no argument—only divine confrontation. Likewise, Lydia’s heart was not persuaded by syllogism but opened by God. Pharaoh heard many times, but only hardened further. Each of these represents not merely different outcomes, but different ontological events: the timing and type of confrontation were sovereignly governed, yet the moral responsibility was never removed.

In the submetaphysical model, we clarify what Paul assumes but does not parse:

That faith follows confrontation, not cognition. That hearing is not salvific, but preparatory. That conviction does not arise from information, but from the ontological breaking of resistance before a Person who exposes, not merely proposes.

Thus, we do not revise Paul’s theology. We reveal its layered architecture—upholding apostolic authority while resisting the modern tendency to flatten theological shorthand into mechanistic sequences.

This disambiguation preserves:

The mystery of divine initiative,

The moral urgency of relational surrender, and

The irreducibility of faith as both gift and response—ontologically anchored, relationally demanded, and temporally unveiled.

Faith is not subjective confidence in something hoped for, but the subjective ratification of an objective confrontation—a covenantal submission to ontological truth already revealed. Because faith is ontological submission to revealed truth, it cannot remain a mere correlation to inner preference—it ratifies a covenant already initiated by the Revealer. Revelation is objective: it proceeds from God, confronts the moral agent, and presses upon the soul with propositional force. The agent’s response may be subjective—tender or resistant—but the faith that emerges in submission to that revelation shares in the objectivity of its source. Faith is not what makes the confrontation real; it is what acknowledges that the confrontation has already occurred and consents to be governed by it. Thus, faith does not invent meaning—it yields to it. It is not an inward aspiration, but a moral alignment. This redefines faith not as private sincerity, but as covenantal submission to a revealed reality.

Modern discourse frequently treats faith as a correlational phenomenon—a subjective belief that loosely aligns with one’s hopes, values, or experiences. It is often defined as a kind of inward projection that finds existential meaning in the possibility that something unseen may be true. Under this view, faith is not grounded in a revealed reality but justified, if at all, by its psychological or social utility.

Thus, what is often framed as “subjective faith” is in fact a miscategorization of the subjective response, not of the faith itself, which remains grounded in relational objectivity.

But within the relational–ontological framework presented here, faith is categorically not correlational. It is not the attempt of the self to connect with transcendent meaning. Nor is it an affective preference justified by internal coherence. Rather, faith is the agent’s response to objective, morally confronting truth, relationally revealed by God.

Faith is not the construction of meaning—it is the ratification of a covenant already initiated by the Revealer. Through epideictic confrontation, God discloses Himself—whether by Word, providence, or spiritual disruption—and summons the moral agent into alignment. This confrontation is not neutral; it is propositional, moral, and deeply personal. The soul is pressed to a verdict: to yield or to resist. That moment—the elentic response—is the hinge of moral destiny. Where there is submission, faith is born—not as projection, but as the agent’s consent to be governed by what has been revealed.

This makes faith contractual in structure. God initiates the covenant by confronting the agent with ontological truth. The agent, in responding positively—repenting, trusting, yielding—ratifies that covenant relationally. The faith does not create the reality; it accepts and seals it. Faith is not what makes God’s Word true. Faith is what acknowledges that God’s Word has already confronted the soul, and it consents to be governed by it.

Therefore, faith is not subjective optimism about things unseen. It is the moral consent to relational truth already revealed—and by consenting, it enters into a binding ontological relationship.

The modern privileging of subjectiveness dislocates objectivity—not by denying the existence of truth, but by quietly relocating its center from the Revealer to the receiver. In so doing, it transforms faith from covenantal submission to private meaning, and forfeits its ontological integrity.

This reframing restores faith to its rightful place: not as private belief, but as the soul’s covenantal ratification of divine confrontation.

This gift–conviction dialectic is mediated by the Spirit. The Spirit impresses divine disclosure upon the conscience, producing conviction; upon ratification the Spirit indwells, and in that indwelling the believer participates in the Son’s fidelity. Whether or not the believer explicitly understands this mechanism, it is through the Spirit that Christ’s authored fidelity becomes our lived reality.

When God confronts a moral agent, the soul stands at a crossroads. If it yields, the movement is repentance; if it resists, it becomes rebellion. Faith precedes and empowers the first, and is denied or distorted in the second. Christ Himself entered this crisis. In Gethsemane He voiced natural human shrinking before death—“let this cup pass from me”—yet immediately subordinated His will to the Father’s. This weakness, submitted rather than indulged, is the very ground of His sympathy. He succours us not as an aloof exemplar but as One who has borne temptation from within and prevailed.

Repentance is not a surge of emotion. It is a moral turning—a deliberate re-orientation rooted in ontological submission. Once the soul acknowledges the Revealer’s authority, it cannot remain inert; it bends, confesses, and realigns.

Rebellion, by contrast, may wear pious clothing. It can appear in religious zeal, intellectual assent, or emotional fervour—yet all the while retain epistemic autonomy. It does not always reject truth outright; it simply refuses to be mastered by it.

A single scene in Genesis 4 makes the contrast vivid: God confronts both Cain and Abel. Abel’s offered gift signals humble alignment; he accepts God’s terms and is received. Cain, warned that “sin is crouching at the door,” nevertheless clings to wounded pride. His refusal to yield—first in worship, then in rage—culminates in fratricide. Under identical divine exposure, repentance flowers in Abel, while rebellion hardens in Cain.

Thus faith cannot be measured by outward performance or emotional tone. Its authenticity is disclosed by its moral reflex: does the soul, like Abel, yield and turn, or does it, like Cain, preserve control and simulate fidelity?

Once divine confrontation has occurred, no response remains neutral. Apparent evasions—such as “I don’t have faith,” “I’m undecided,” or “I believe in a higher power but not in specific terms”—are not morally passive positions. They are not suspended states of epistemic humility, but acts of deferred submission. The absence of decisive faith, after objective revelation, is not a lack of opportunity—it is a noetic posture of resistance and rebellion. The soul has been summoned and confronted; to delay is to decline, to hedge is to resist. These evasions, often couched in ambiguity or spiritual openness, conceal an underlying rejection of moral surrender. The agent is not awaiting more truth—they are withholding response to the truth already revealed. In this light, even silence becomes verdict, and indecision becomes rebellion. For every soul that has encountered divine confrontation, the question is no longer “What do I believe?” but “What have I done with what I was shown?”

This moral accountability is essential to theodicy: without it, divine justice collapses into arbitrariness, and God could be justly accused of condemning those who were never truly confronted. See Appendices C and C2 for further discussions on Theodicy.

The ontological confrontation that gives rise to faith also reorders the structure of knowing. Before submission, epistemology dominates: the self interrogates truth, demands evidence, and seeks assurance on its own terms. Because faith—as Section III-A established—is a covenantal ratification, not a subjective correlation, the moment that covenant* is sealed epistemology no longer leads but follows. Once the Revealer is acknowledged, the soul undergoes a transformation: epistemology recedes. (See detailed discussion in essay on Epistemology ).

This is not to say that reason is abandoned. Rather, reason is restored to its proper place—no longer governing, but governed. Epistemology is now ordered by revelation, not by autonomy. The soul no longer interrogates reality; it receives it. It no longer manages truth; it is managed by it.

This is precisely what Proverbs 1:7 affirms: “The fear of the Lord is the beginning of knowledge.” Faith does not emerge from epistemic certainty; it makes knowledge possible by aligning the soul reverently with truth. The intellect follows where the soul has already bowed.

Faith, then, is not anti-rational. It is pre-rational in structure and meta-rational in outcome. It authorises reason, not by supplying evidence, but by placing the agent in relation to the ontological source of all evidence.

Not all Christian traditions preserve the structure of faith as an ontological act. The Reformation was, at its heart, a reordering of the soul’s relation to divine confrontation. It was not merely about ecclesiastical independence or doctrinal precision—it was a restoration of how God addresses the soul and how the soul responds.

In Roman Catholicism, the structure of faith became mediated through the Church. The believer’s relation to God was filtered through sacraments, priesthood, and ecclesial tradition. Faith was redefined as assent to what the Church teaches—not as direct submission to the Word of God.

Eastern Orthodoxy preserved a vision of divine mystery and participation but emphasized sacramental theosis over moral confrontation. The soul was drawn upward into God’s life, yet the sharp, prophetic demand of repentance and judgment was often muted.

Even much of modern Protestantism has lost the relational core, fragmenting into emotionalism, moralism, or pragmatism. In many circles, faith has again become subjective, therapeutic, or performative.

Without denying that God has wrought genuine believers in other settings, only the Reformation proper—as a theological rediscovery—reclaimed faith as the soul’s direct response to God’s revealed Word. Its central doctrines—sola fide, sola Scriptura, and the priesthood of all believers—were not abstractions; they were a structural restoration of faith as unmediated moral submission to divine self-disclosure.

Thus, it is not the label “Protestantism” that preserves valid faith, but the theological act of the Reformation that recovered its ontological center.

Faith is rational not because it supplies an explanation but because it aligns the believer with the Son’s filial fidelity to the Father, mediated by the Spirit. Rationality here is participatory, not originative. In other words, epistemic clarity flows from faith, never into it: the mind becomes fruitful only after it surrenders its autonomy. Faith is therefore no wager or retreat—it is the return to reality that alone makes genuine certainty possible.

The ontological grounding of faith as relational submission to objective revelation leads inevitably to a relational model of salvation. If faith is not an inner performance, but covenantal ratification, then salvation is not a transactional reward, but a relational realignment. The decisive act is not merit, but consent. This reframes salvation as a response to being confronted and invited—not as an achievement, but as an ontological joining. It is not what one has done, but who one has yielded to, that determines one’s position before God.

Faith is not a leap into the unknown. It is a step into what has already been disclosed. It is the soul’s acknowledgment that truth is not a proposition to be tested, but a Person to whom one must yield. Faith begins where argument ends—not because it bypasses reason, but because it restores reason to its proper place.

What this appendix has demonstrated is not merely a refined definition of faith, but a reclassification of its metaphysical category. Faith has long been misinterpreted as a subjective state—irrational, emotional, or epistemically weak. It has been treated as psychological projection, a spiritual instinct, or a noble wager. But each of these framings shares the same fatal flaw: they relocate faith from the Revealer to the revealee, making it a capacity of the self rather than the soul’s response to the One who confronts.

In this framework, that displacement is reversed. Faith does not begin in the human subject; it begins in divine initiative. It is not correlational but covenantal. It is not subjective confidence but ontological submission. Faith is not the invention of belief, but the ratification of relational truth—truth revealed in the very act of moral exposure. It does not grant legitimacy to the unseen; it acknowledges that the unseen has already been disclosed, and it consents to be governed by it.

It is also important to distinguish faith from its ongoing expression. Faith, as we have defined it, is binary—the soul’s covenantal consent to reality already disclosed. One either yields or resists; there is no neutral ground. Yet once that alignment is present, trust begins to grow as its lived expression. Like leaven, it permeates every area of life, shaping decisions, priorities, and affections. Trust is not a second act of faith, but the deepening surrender that flows from the initial “Yes” to God’s summons. Faith anchors the soul once for all, while trust progressively manifests that anchoring in every sphere of life.

This is the threshold: not belief as imagination, but faith as realignment. Not the construction of meaning, but the surrender to meaning already revealed. Faith is not subjective assent. It is the first act of relationally restored being.

And so the crisis of our age is not a crisis of faith but a crisis of ontology. Faith, rightly understood, is not the casualty of that crisis but its clearest resolution. It is the soul’s covenantal conviction that what God has disclosed is true—and by consenting to it, the soul steps fully into reality.

This ontological reclassification presses inevitably toward operation. What Christ authored is what the Spirit makes operative in us: fidelity that endures when sense fails. The saints ‘keep the faith of Jesus’ (Rev 14:12) not as a transferable substance but as the lived retention of His fidelity within. Paul’s witness in Galatians 2:20 sums the matter: life in the flesh is no longer animated by autonomous resolve, but by union with the Son whose authored fidelity now indwells the believer. This is why endurance is possible: ontology yields praxis because His faith is kept in us. In this way ontology yields praxis: the believer’s endurance is the fruit of union with the One whose faith did not fail, and whose fidelity is now kept in them.

This ontological reclassification of faith does not diminish the church’s role in evangelism—it clarifies it. The church does not create faith, nor does it initiate the confrontation that produces it. That work belongs to God alone. But the church is entrusted with a sacred task: to make the truth of God’s Word present and clear, so that divine confrontation may occur wherever the Spirit chooses to act.

Faith, as we have seen, is binary: the soul either consents to God’s summons or resists. Yet the church is called not only to witness that threshold moment but also to nurture the trust that flows from it. Once faith is present, trust begins to permeate the believer’s entire life, shaping daily decisions, affections, and loyalties. This is the leavening work of discipleship: helping believers learn to yield, in increasing measure, every sphere of life to the One to whom they have already said “Yes.”

Thus, the church’s mission is twofold. First, to proclaim the Word faithfully, discerning the signs of divine conviction and walking alongside those who are being drawn. Second, to shepherd believers into deeper trust, so that the initial covenantal alignment of faith matures into a comprehensive surrender to God’s reality.

When the church understands that it is not the source of faith but the servant of the Revealer, it ceases striving to manufacture conversions. Instead, it creates space for the Spirit’s work—guarding the gravity of God’s truth and guiding souls into its ever-expanding orbit.

Footnote

*Covenant , in this context, refers to a God-initiated ontological relationship, established through self-disclosure and morally ratified by the agent’s faith. It is not a mutual agreement between equals, but a divine summons to which the soul either yields or rebels.