This essay reconsiders the biblical phrase “walking in the Spirit” through an ontological and relational lens, arguing that it denotes not behavioral improvement but the reconstitution of the moral agent in fidelity to divine typology. Against prevailing reductions—whether moralistic, experiential, or mystical—the essay advances a framework in which law functions epideictically, not punitively, and Spirit-led regeneration resolves the ontological disjunction exposed by that law. In doing so, it also addresses theological objections rooted in Romans 7, showing that divine exposure, far from undermining theodicy, vindicates it by pairing confrontation with real ontological invitation.

The phrase “walking in the Spirit” is often flattened into categories that fail to grasp its ontological depth. For some, it is understood experientially—as an inward sense of divine presence, peace, or intuition. For others, it is treated morally—as a commitment to virtuous conduct or obedience. In some traditions, it is mystified entirely, associated with ecstatic phenomena, private impressions, or spiritual impulses loosely tethered to Scripture.

Each of these conceptions reflects a partial truth, but all fall short of the deeper theological and ontological reality. What is missed is that walking in the Spirit is not primarily experiential, ethical, or mystical—it is ontological. It signals a shift not merely in how one behaves or feels, but in what kind of being one is becoming. It marks the reconstitution of the moral agent in relational alignment with the ontotypical standard defined by God.

To walk in the Spirit is to participate in sanctification through faith—a process not grounded in personal effort but in divine relational union. This is not moral performance, but moral reformation by proximity: the will realigned, the heart reborn, and the type renewed. It is and confirms, in essence, a relational soteriology. The goal is not to meet an external performance standard, but to be drawn into a restored relational structure through which moral conformity becomes ontological participation.

This renewed agent then begins to be confronted with and engaged with God-ordained moral choice sets—decisions not randomly encountered, but sovereignly structured to reveal the agent’s true posture. These choice sets serve as crucibles, not tests of performance, but sites of revelation: they show whether the regenerated will is disposed toward God or still harboring resistance. It is not that the Spirit merely empowers better decisions; it is that the entire volitional landscape is redefined from the inside out.

The law may define and delimit the type, but it cannot produce it. The Spirit, however, brings the agent into real alignment—not informationally, but ontologically. Yet this inhabitation is not automatic. It must be preceded by the disclosure of latent posture, a confrontation made possible only by prevenient grace. That grace presses the soul into a moment of moral exposure—an epideictic unveiling in which the will is either surrendered or simulated.

The thesis of this essay is therefore simple but far-reaching:

To walk in the Spirit is to undergo an ontological reconstitution, wherein the moral type defined by divine law is no longer mimicked through external conformity, but fulfilled through internal participation. This is not self-transcendence or incremental betterment, but the gift of relational fidelity—the transformation of the agent into one who wills what God wills because they now walk not alongside, but within, the Spirit.

This reconstitution, however, is not given to avoid crisis but to withstand and reinterpret it. The aim of Spirit-walking is not merely to disclose weakness or latent rebellion; it is to invite the soul into deeper alignment even amid moral exposure. If there is surrender, then the confrontation becomes an act of divine grace: God is not condemning, but exposing in order to invite acknowledgment, deconstructing the false scaffolding of autonomy, and reconstructing the soul in fidelity to the ontological type defined by Himself.

This arc of exposure and transformation is not abstract; it is embodied in Christ Himself. His prayer at Gethsemane— "if it be possible, let this cup pass… nevertheless not my will, but thine be done” —is not a moment of failure, but a holy admission of human weakness. In that moment confessed weakness, Christ was not exhibiting sin but identifying fully with the creature’s dilemma, becoming thereby a truly empathetic High Priest. As Hebrews declares, He was “in all points tempted like as we are, yet without sin” (Heb. 4:15). His confession was not for His own sake, but for ours—so that He might intercede not merely as a substitute, but as a brother who has walked through the crisis of volition from within the human frame.

In this, Christ reveals the true nature of Spirit-walk fidelity: not the absence of struggle, but the transcendence of rebellion through volitional submission. The Spirit does not bypass weakness, but inhabits it—to expose, invite, unmake, and remake the agent in righteousness.

If walking in the Spirit represents relational ontological participation in God’s moral type, then the law must be understood not simply as a set of rules but as a delimiting revelation of that type—a scaffold of moral intelligibility. The Ten Commandments, in particular, function not as arbitrary stipulations, but as anaphytic ontotypological markers—defining the outer bounds and structural constraints of what righteousness must be, even though they do not bestow the power to inhabit it.

The law is thus an anaphytic disclosure—meaning it sets boundaries from below, outlining the minimal ontological structure that makes moral life possible. It is delimiting in that it defines what righteousness is not, even while it leaves the soul still longing for the power to be what righteousness requires. In this way, the law is typological, not performative: it maps moral being from the outside but cannot generate it from within.

Scripture affirms this. Paul writes that “the law was added because of transgressions” (Gal. 3:19)—not to solve sin, but to reveal and intensify it, pressing the soul toward the crisis of impossibility. It was temporary and pedagogical, not eternal in form. It functioned as a gaoler and a schoolmaster, hemming in the rebellious will until the arrival of faith (Gal. 3:23–25). Hebrews 8:13 likewise notes that the old covenant is “ready to vanish away”—not because its content was false, but because its structural function was incomplete.

In the relational-ontological model, this pedagogical role is not merely forensic or covenantal, but deeply metaphysical. The law does not merely convict—it confronts the soul with the impossibility of autonomous fulfillment. It shows that to be moral is not to behave rightly in isolation, but to be rightly constituted in relation to the Source of righteousness. The law becomes a mirror in which the rebellious agent sees both the rightness of God’s type and the wrongness of their own posture. It reveals what the soul ought to be—and, in doing so, reveals what it is not.

Thus, the law is ontologically valid but functionally temporary. Its permanence lies not in its textual formulation, but in the structure it reflects—God’s moral character and the relational ordering of the moral cosmos. Once the Spirit is given, the agent no longer merely sees the type from without, but begins to embody it from within. Yet the law retains a residual purpose: not as the means to righteousness, but as the epideictic backdrop against which true moral transformation becomes visible.

The purpose of the law is not to manipulate the will but to expose it. God does not engineer rebellion, but reveals the moral condition already latent in the soul. This is epideixis—not coercion, but disclosure. It is the unveiling of volitional posture in the presence of ontologically instantiated truth.

The crisis, then, is not divine intrusion, but a providentially ordered disclosure—a moment in which suppressed moral reality is brought into view. The law does not cause rebellion; it occasions its manifestation. It is not a behavioral constraint, but a revelatory frame in which the soul’s alignment (or misalignment) becomes visible.

Whether the result is repentance or resistance, the crisis serves a singular purpose: to make volitional posture morally undeniable. It collapses the illusion of neutrality and renders divine judgment just—not because rebellion is provoked, but because rebellion is unmasked.

The term epideixis (ἐπίδειξις) means “display,” “demonstration,” or “unveiling.” In theological usage, it refers to the ontological disclosure of the soul’s moral posture when confronted by divine reality. It does not initiate moral distortion, but renders existing disposition explicit.

The law performs this epideictic function—not by provoking transgression, but by removing concealment. It renders visible what was psychologically or socially obscured. This clarity is not manipulative; it is a grace of truth.

The Deontic–Modal Unit (DM Unit)—God’s moral architecture embedded in the soul—is not newly activated in such moments. It is always present, suboperatively. What changes is not structure, but exposure. The agent’s response to this clarity determines whether it aligns with divine moral order or suppresses it anew.

Epideixis forces a revelatory juncture. The will must either yield or simulate. Where surrender is refused, the agent constructs pseudo-alternatives—false moral projections or compensatory schemas—that mimic alignment while preserving autonomy.

The Ten Commandments exemplify this epideictic function. As anaphatic moral delimiters, they do not incite new rebellion, but confront the soul with the revealed moral type of God in concentrated form. Their clarity brings the latent volitional state into view. This is the antithesis of psychological provocation. God does not incite disobedience, nor manufacture collapse. He unveils what is.

The Decalogue thus functions as a calibrated moral mirror. It does not impose posture, but renders posture undeniable. In this disclosure, the soul enters the elentic threshold—the morally charged state in which volitional posture is no longer buffered by ambiguity. It is here that the will confronts the unveiled truth and must either align or resist. Elentics is not a separate divine act, but the internalized moral consequence of epideixis. It names the soul’s exposed condition, not the exposing itself. The one who suppresses truth at this threshold simulates fidelity; the one who yields is reoriented by grace.

“Let no man say when he is tempted, I am tempted of God: for God cannot be tempted with evil, neither tempteth he any man.” (James 1:13)

This reinforces the distinction between divine confrontation and moral entrapment. Epideixis discloses; it does not provoke. The agent’s rebellion is not fabricated—it is revealed.

The moral crisis is not coercively engineered by God, but deliberately permitted and epideictically occasioned. It is triggered by the agent’s proximity to unveiled moral truth. The law does not provoke the will—it reveals its posture. This is a vital distinction: God does not create rebellion; He brings it to light.

In this moment of confrontation, the agent faces a volitional bifurcation...

Repentance leads to surrender to the claims of the deontic–modal (DM) unit—a fixed, divinely imprinted structure always present within the moral agent. Though the DM unit itself does not change, the agent’s volitional response, the noetic posture to it determines whether it is suppressed or yielded to. In repentance, this surrender initiates axiological requalification—a realignment of the soul’s value structure toward the divine good, effected, eventually, through sanctifying grace by faith. As a result, the noetic postures are brought into congruence with divine values, forming a Spirit-animated volitional structure. This sanctifying reconstitution does not bypass agency; it restores it to fidelity. It is a gradual, lifelong process—what Scripture calls the crucifixion of self (Galatians 5:24), and walking in the Spirit rather than the flesh (Romans 8:1–4).

Suppression, conversely, results in hardening. This is not passive ignorance but an active denial of the DM unit’s claim on the conscience. Like Pharaoh, such a soul rejects truth and is eventually abandoned to its own moral delusions (Rom. 1:28; 2 Thes. 2:10–12). The will resists disclosure and chooses instead to simulate moral alignment through pseudo-instantiation. The moral type is mimicked, not inhabited. This reconstruction of moral presence without true ontological fidelity is the essence of spiritual fraud—and the crisis does not cause it, but unmasks it.

Thus, epideictic confrontation clarifies, but does not coerce. The moment of crisis does not invent the posture—it reveals its actual depth.

This model preserves divine justice by maintaining the sharp line between provocation and disclosure. God is not culpable for the soul’s rebellion; He is faithful to present truth, knowing that the agent’s response to that truth will expose its real condition.

The law, in its epideictic role, vindicates God by: making hidden rebellion visible, demonstrating the ontological impossibility of autonomous righteousness, providing the context in which true surrender or simulated compliance is revealed.

This is the theodictic center of the relational model: God is not arbitrary, and grace is not mechanical. Truth is revealed to elicit response—but never to predetermine it. The law functions not as a punitive imposition, but as a diagnostic instrument. It exposes not only the lack of moral power, but the absence of volitional surrender. And in so doing, it justifies God’s call to repentance as righteous, relational, and ultimately merciful.

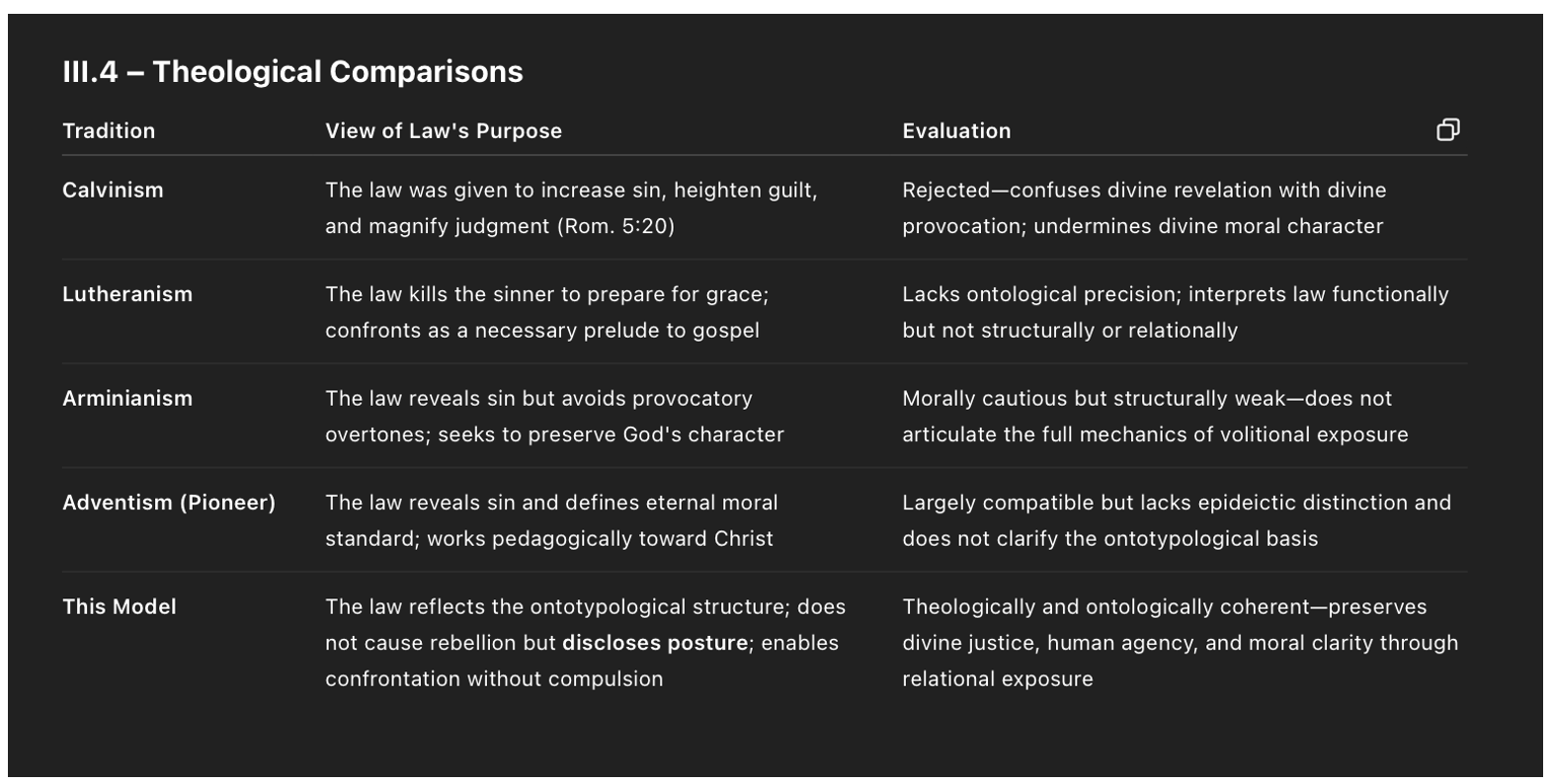

Purpose: Demonstrate how the law and divine confrontation function epideictically—not to provoke but to expose—and how this precipitates either volitional surrender or ontological resistance.

While the law defines moral structure in the abstract, biblical narratives give us embodied case studies in which epideictic exposure draws out the moral posture of agents. In both resistance and repentance, the law and its analogues do not manipulate—they disclose. Each encounter becomes a test—not because God imposes it as such, but because truth inevitably divides.

Pharaoh (Exodus 5–14) serves as a paradigm of progressive resistance to ontological disclosure. God repeatedly confronts him—not with coercion, but with clarity: prophetic warnings, miraculous signs, and escalating moral appeals. These confrontations are epideictic: they expose, rather than produce, Pharaoh’s posture.

The statement that “God hardened Pharaoh’s heart” must be understood not as divine manipulation but as divine persistence in disclosure—allowing what is latent to become manifest. The more truth is presented, the more the entrenched will resists surrender.

With each confrontation, Pharaoh enters the elentic threshold—the morally clarified state where his volitional posture stands exposed. He is not manipulated into rebellion; he is confronted with unveiled reality and refuses to yield.

Pharaoh does not invent rebellion in reaction to God; rather, his rebellion becomes visible through sustained exposure. The result is not arbitrary judgment, but ontological self-sealing: a rejection of relational surrender, a hardening into pseudo-authority, and a clinging to power without truth.

The claims of the DM unit remain ever present, but Pharaoh’s will refuses to yield noetically. This is not divine override but relational abandonment (cf. Rom. 1:24)—where the refusal to love truth (2 Thes. 2:10–12) culminates in being given over to one’s delusions. Pharaoh becomes a case study in how epideixis, when resisted at the elentic threshold, leads not to transformation but to entrenchment—vindicating both divine justice and the moral coherence of judgment.

Paul’s Damascus Road encounter (Acts 9:1–9) presents the contrasting arc to Pharaoh: a volitional surrender in response to an overwhelming epideictic rupture.

Though self-righteously zealous for the law, Paul is ontologically misaligned—fervently moral, yet fundamentally out of step with divine fidelity. The resurrected Christ interrupts not to humiliate, but to confront in love: “Saul, Saul, why persecutest thou me?” This theosonic moment shatters his epistemic framework and exposes his moral posture.

Paul is not forced; he is confronted. But the weight of unveiled truth renders suppression unsustainable. Here too, the soul enters the elentic state—a moment of volitional clarity where Paul must either suppress the revealed Christ or surrender. His immediate response—“Lord, what wilt thou have me to do?”—marks the surrender of simulated authority and the acknowledgment of the DM unit’s rightful claim.

From this noetic self-surrender, sanctification can begin. Paul’s values (Axiology), duties (Deon), and possibilities/prohibitions (Modality) are reconstituted around Christ. The moral type is no longer pursued through effort, but inhabited relationally. This is not moral performance but ontological regeneration.

Paul’s conversion illustrates the essence of epideixis: it does not coerce the will, but reveals the soul. Elentics is the interface where this revelation is received or resisted. Where Pharaoh resisted, Paul yielded—and became a vessel through whom that same epideictic light would confront the world (Acts 26:18; 2 Cor. 4:6).

Purpose: To expose the counterfeit resolution to moral confrontation—when the soul aligns externally to the moral form without undergoing relational reconstitution. This section reveals how legalism is not merely a behavioral error but a deep ontological evasion.

Legalism emerges when the moral type (as revealed in the law) is treated as a template for behavior rather than a call to relationship. The agent conforms externally to the ontotypological structure but avoids the internal surrender required for alignment with the divine will.

This is not moral obedience—it is ontological evasion. Legalism treats the law as a performative code, a ladder for achievement or merit. But the noetic postiure is not engaged; the will is not surrendered; the relational axis remains autonomous. The law becomes a mask rather than a mirror.

Legalism, in this light, is not merely “strictness” or “rule-keeping”—it is a moral simulation that bypasses the heart of sanctification: walking in the Spirit. It satisfies the eye of the religious system while bypassing the eye of divine exposure.

While legalism begins as surface-level behavioral conformity, it often slides into effigiation when the agent not only mimics moral conduct but falsely assumes moral identity—claiming typological legitimacy without relational surrender.

Where legalism governs conduct, pseudo-instantiation governs identity. The agent mimics the moral type—performing righteousness as though it were ontologically possessed. This is more than hypocrisy; it is spiritual counterfeiting. The soul constructs a semblance of alignment that substitutes for actual regeneration.

This posture arises at the point of epideictic confrontation, when the agent chooses control over surrender. Rather than yield to the claims of the DM unit and undergo gradual inward transformation, the will simulates sanctity in order to retain autonomy. The result is a false moral presence: a behavioral shadow with no spiritual substance.

This is the essence of pseudo-instantiation: the moral type is replicated without the indwelling source; the agent operates within moral grammar without moral essence. The Spirit is not openly resisted, but structurally circumvented. Identity is assumed rather than received, performed rather than participated in.

Effigiation is the semiotic counterpart to pseudo-instantiation. It is the symbolic or behavioral projection of holiness without ontological legitimacy. The agent embodies a type that has not been granted—a form without divine instantiation. In biblical terms, this is what Jesus condemned in the Pharisees: “Ye are like whited sepulchres…” (Matt. 23:27). It is not merely hypocrisy, but the appropriation of sacred typology without relational union. The form of godliness is assumed, while the power thereof is denied (2 Tim. 3:5). Effigiation is a fraud against both ontology and relational truth. It claims a moral place in the order of being that has not been received through surrender. It is type without authorization, image without indwelling, presence without fidelity.

Ontological transformation results not from performance but from union—such that in the regenerated walk, the moral law is no longer external or conscious, but internally fulfilled by participation in divine life.

Walking in the Spirit is not ethical refinement or mystical escapism. It is the cataphytic fulfilment of the moral law—that is, the positive outworking of ontological union. The moral type is no longer approached as command or boundary; it is inhabited as the overflow of divine indwelling.

Romans 8:4 captures this paradox: “That the righteousness of the law might be fulfilled in us, who walk not after the flesh, but after the Spirit.” The Spirit does not help the agent fulfil the law as an external code. Rather, He animates the moral structure from within, enabling a correspondence of life and type.

This is not imitation but ontological participation. The agent no longer acts in moral anxiety or performance—because fidelity is not a burden carried, but a life shared.

Galatians 5:22–23 ends the list of the fruit of the Spirit with this statement: “Against such there is no law.” This is more than poetic closure—it is a theological axiom. When the agent walks in the Spirit: the law is not needed as external constraint. The DM unit becomes dormant—not because it ceases to exist, but because its diagnostic function is no longer required. The soul has entered into a prelapsarian (Edenic) alignment where duty is indistinguishable from delight, and law has become latent within love. In this state, axiology and telos coincide. The good is not performed under duress or deliberation—it is desired and done without internal dissonance. This mirrors Eden, where moral volition required no mediating scaffolds because the agent was in direct relational correspondence with the divine.

This is not antinomianism. The law is not destroyed, but transcended—its telos realized in Spirit-led ontological fidelity. Hebrews 8:10 affirms this new alignment: “I will put my laws into their mind, and write them in their hearts.” This is not merely memory—it is reconstitution. The moral structure is preserved, but no longer as a gaoler—it has become a vessel of resonance. It is now fully aligned with the internal harmony of Spirit-animated life. The agent is not morally autonomous, but relationally suffused.

In this state: the DM unit becomes non-reactive—not because it is absent, but because it is now harmonized. The moral life no longer moves from axiology → deontology → modality → praxis, but from axiology to spontaneous fidelity, bypassing the layers that were only necessary in the postlapsarian crisis. This is freedom not from obligation, but from disjunction. The Spirit leads not by rule, but by resonance—and in such alignment, there is no need for law.

The moral law is neither annulled nor obsolete—it is transcended in function, yet preserved in being. Ontologically, the moral law remains intact, reflecting the anaphatic boundaries of divine order. But functionally, in the fully Spirit-led life, its role becomes dormant—not because it is denied, but because it is fulfilled. The agent no longer needs the law as external directive, for the moral type is now internally animated. This dormancy is not negation—it is resonance. In walking by the Spirit, the law's telos is realized: not as suppression, but as synchrony. Thus, the law abides as the silent scaffold of moral order, no longer imposed, but indwelt.

The Spirit-walk does not merely fulfil moral expectations—it discloses and vindicates the character and order of God in the great theodictic drama.

The walk in the Spirit is more than personal sanctification—it is a relational and ontological witness. Every act of surrendered fidelity is a living rebuttal to the primal accusation: that God’s order is oppressive, manipulative, or unjust.

Lucifer’s claim in Eden—that divine governance suppresses autonomy—is refuted not through force but through freely chosen correspondence. Those who walk in the Spirit embody an ontological restoration that declares: “His commandments are not grievous” (1 John 5:3). This is not only justification—it is vindication. The Spirit-walk becomes an epideictic act: God displays His own goodness through the moral reconstitution of those who trust Him.

In the Adventists' Great Controversy frame, the moral law has often been misrepresented as arbitrary imposition or as a provocation to sin. But in this model: the law is anaphytic—revealing ontotypical boundaries that define moral being. It is pedagogical—serving as a mirror, not a manipulator. It is epideictic—exposing latent posture without engineering response.

God does not use the law to induce failure, but to reveal it. And this revelation is preparatory—not punitive—for the relational invitation to follow. The law, therefore, serves its purpose in proportion to the agent’s proximity to grace.

Clarification on the Adventist Framing of the Law Traditional Adventist theology rightly upholds the law as central to God’s justice and moral order. However, some articulations risk portraying the law as an instrument for inducing guilt or failure in order to drive souls to grace. This model clarifies that the law does not provoke rebellion but exposes it. Rebellion is not the product of divine orchestration, but the manifestation of the soul's posture when confronted with truth. In this light, the law is not salvific nor condemnatory in itself—it is revelatory. Its function is to clarify the agent’s alignment to the moral order already made visible through grace.

Final judgment, in this framework, is not the weighing of behavioral compliance but the public unveiling of volitional orientation: did the soul surrender to the confrontation of epideictic truth? Did it embrace the regenerative realignment offered in the Spirit? Or did it simulate righteousness through pseudo-instantiation, masking rebellion beneath performance? Divine judgment, then, is not retributive but revelatory. It discloses whether the agent entered into ontological fidelityor clung to moral simulation.

This is why Revelation portrays judgment in visual and narrative terms: books opened, witnesses revealed, characters unmasked (Revelation 20:12). God does not condemn—He discloses. And the walk in the Spirit is both the evidence and embodiment of that vindication.

The final generation—the remnant who walk fully in the Spirit—function not merely as survivors but as proof. Their lives, formed not by fear but by relational fidelity, become the epideixis of divine trustworthiness.

In the eschaton: the law no longer accuses, for it has been fulfilled from within. The DM unit no longer cries out, for the conscience is aligned. The Spirit does not strive, but walks in union, for the will is synchronized. This is the final answer to the accuser. Not in argument, but in embodiment. “Here are they that keep the commandments of God, and the faith of Jesus” (Revelation 14:12)—not as external burdens, but as the overflow of ontological union.

Romans 7 has often been weaponized—either implicitly or explicitly—as a challenge to divine justice. Critics contend that if God reveals moral truth to the conscience, yet the will remains impotent to perform it, then God stands accused of provoking the soul unto despair or failure. This logic subtly undercuts theodicy by implying that divine exposure entails divine cruelty: God shows the good but withholds the power to attain it.

But this reading is both theologically and ontologically deficient. Paul is not attributing moral futility to divine design, but testifying to the fracture within the self when the will remains autonomous. Romans 7 dramatizes what occurs when the fixed deontic–modal (DM) structure—always present by virtue of image-bearing—is illuminated by the law, but not yet surrendered to grace. The crisis Paul describes arises not from the activation of a new faculty, but from the volitional failure to align with what is already ontologically present. The law is holy—but apart from relational realignment, the soul remains self-reliant and disordered.

Thus, what is exposed in Romans 7 is not a flaw in God, but the futility of moral striving apart from the Spirit. Paul’s cry—“O wretched man that I am!”—is not an indictment of God for demanding too much, but a confession of internal misalignment and the inadequacy of performance-based righteousness (Rom. 7:24). The passage leads not to despair, but to a necessary gradual crucifixion (Gal 2:20) of self: a surrender of autonomy in favor of relational, Spirit-enabled, gradual (Gal 5:22) alignment (Rom. 8:1–4). What appears to be condemnation is in fact confrontation—designed not to crush, but to clarify.

This framework affirms that prevenient grace never exposes without offering. It confronts, yes—but it also awakens memory, summons repentance, and draws the will toward regenerative response. Romans 7 is not the end of the moral drama but its critical turning point. It is epideictic not in order to shame, but to reveal what must be transformed. The Spirit does not merely illuminate what is right—it empowers the agent to embody it. Thus, Romans 8 is the answer to the apparent impasse of Romans 7: “What the law could not do…God did, by sending His Son…that the righteous requirement of the law might be fulfilled in us who walk not according to the flesh, but according to the Spirit” (Rom. 8:3–4).

In this light, epideixis is not provocation but vindication. God’s justice is preserved precisely because His exposure of the soul is paired with a real, ontologically grounded invitation to alignment. The crisis of Romans 7 does not undermine theodicy—it vindicates it, by showing that God has made moral response possible through regeneration, not merely commanded it through law.

Some theological critics, however, continue to invoke Romans 7 as a tacit accusation against divine justice, suggesting that the very act of revealing moral law to a powerless agent is itself a kind of provocation. But this interpretation inverts the logic of the text. God does not awaken futility—He exposes it. The despair Paul voices is not evidence of divine cruelty, but of human estrangement. What Romans 7 discloses is not the failure of divine benevolence but the unsustainability of autonomous moral striving. The crisis is not caused by God, but by the disjunction between law and grace, exposure and empowerment. And precisely here, theodicy is preserved: for every soul so exposed, the Spirit is offered. God's epideictic grace reveals the truth not to mock the will, but to summon it toward relational regeneration.

The journey from legalism to life in the Spirit is not a shift in effort, but a shift in essence. The law was never meant to be the source of life—it was meant to disclose the absence of it. It does not coerce transformation; it exposes the need for it.

In this framework, the law functions as ontological disclosure. It unveils the moral type—the ontotypological structure of righteousness—and thereby reveals whether the soul is aligned or autonomous. Prevenient grace engineers a confrontation with the moral agent: a divinely timed summons that epideictically exposes and elentically arrests the subconscious noetic posture of the heart. This confrontation does not impose guilt, but summons recognition. It is the moment of truth—will the soul surrender to relational realignment, or will it simulate righteousness in order to preserve autonomy?

To align the noetic posture with the precepts of the One True God—that is, to allow the conscience to be requalified and Spirit-animated in harmony with God’s axiological will—is not a legal mechanism. It is a relational and regenerative architecture. It governs not by coercion, but by congruence.

To walk in the Spirit, then, is not merely to behave righteously. It is to be onto-epistemically requalified—to become the kind of being that no longer requires the external delimitations of law, because the internal structure is rightly aligned.

This is why Paul can say, “Against such there is no law” (Galatians 5:23). The telos of the moral law—the ontological kind it describes—is no longer imposed, but indwelling.

The goal is not mere compliance, but conformity to Christ: “Until Christ be formed in you” (Galatians 4:19).

Thus: the law reveals; p revenient grace confronts; the soul, at the elentic threshold, either yields or suppresses; the Spirit reconstitutes; and the agent, through relational surrender, embodies what the law once demanded.

This is not merely a shift in soteriology—it is a full ontological restoration.The law served its purpose—but the Spirit fulfills it: not by cancelling it, but by making its moral reality alive within us.