This appendix emerges not from abstract theorizing, but from a direct confrontation with a recurring failure in modern and even theological thought: the failure to treat truth as an ontological kind (category). It addresses not only how this suppression occurs, but why it is not a mere oversight—it is logically indefensible, intellectually dishonest, and morally evasive.

At the heart of this problem is referential destabilization. Before a thing can be evaluated—morally, logically, or semantically—it must be ontologically stabilized as a kind. This is true for trees, persons, laws—and truth itself. If truth is treated as a shifting function, a linguistic projection, or a social construct, then it cannot be evaluated as truth. Judgment presupposes referential clarity. To deny kindhood is to preempt judgment through semantic sabotage.

If we grant that reality is composed of kinds—tangible and intangible—then truth, like number, causality, and relation, must be classified among the intangible ontological kinds. It is not reducible to syntax, function, or perception. One cannot coherently affirm a structured reality and yet deny truth’s reality. To know anything at all is to presuppose the reality of truth. Thus, to deny truth as a kind is not only to evade being—it is to destroy the foundation of knowing itself.

While moral evasion is indeed central (cf. Romans 1:18), it is not sufficient to explain the breadth of the suppression. The denial of truth as a kind is also:

I.B.2. Intellectually Dishonest

This is not innocent error—it is a simulated intellectual ecosystem, built on suppressed acknowledgment.

This suppression has gone largely unstated in mainstream discourse—even by systems that gesture toward it. This is partly due to:

This is why most modern systems orbit the issue without naming it.

Even theological models often fail here—preferring propositional or systematic truth over ontologically instantiated truth, as found in the person of Christ.

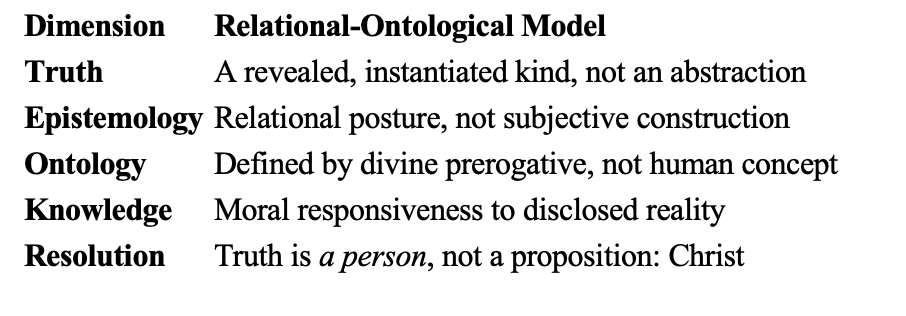

This model explicitly restores what others avoid:

This is what sets this framework apart. It does not merely describe how knowing happens—it exposes when knowing becomes fraudulent by denying its own conditions.

This conversation began with the realization that, while your framework rests on this truth, it had not yet been explicitly stated as an axiom. The suppression of truth is the very root of modern confusion—and so the restoration of truth must be the first step in recovery.

It is not enough for this insight to be implied. It must be named, defended, and placed at the front.

Axiom 1: Truth is an ontological kind. It is not derived from perception or constructed by reason, but disclosed by being—and most fully instantiated in Christ. Any system that denies truth’s reality commits ontological fraud, and any epistemology that avoids its authority collapses into contradiction. To know truth is to be confronted by it. To deny it is not only false—it is intellectually and morally disintegrative.

This is not a theological nuance or a philosophical refinement. It is the line. Every system, every worldview, every method of knowing either:

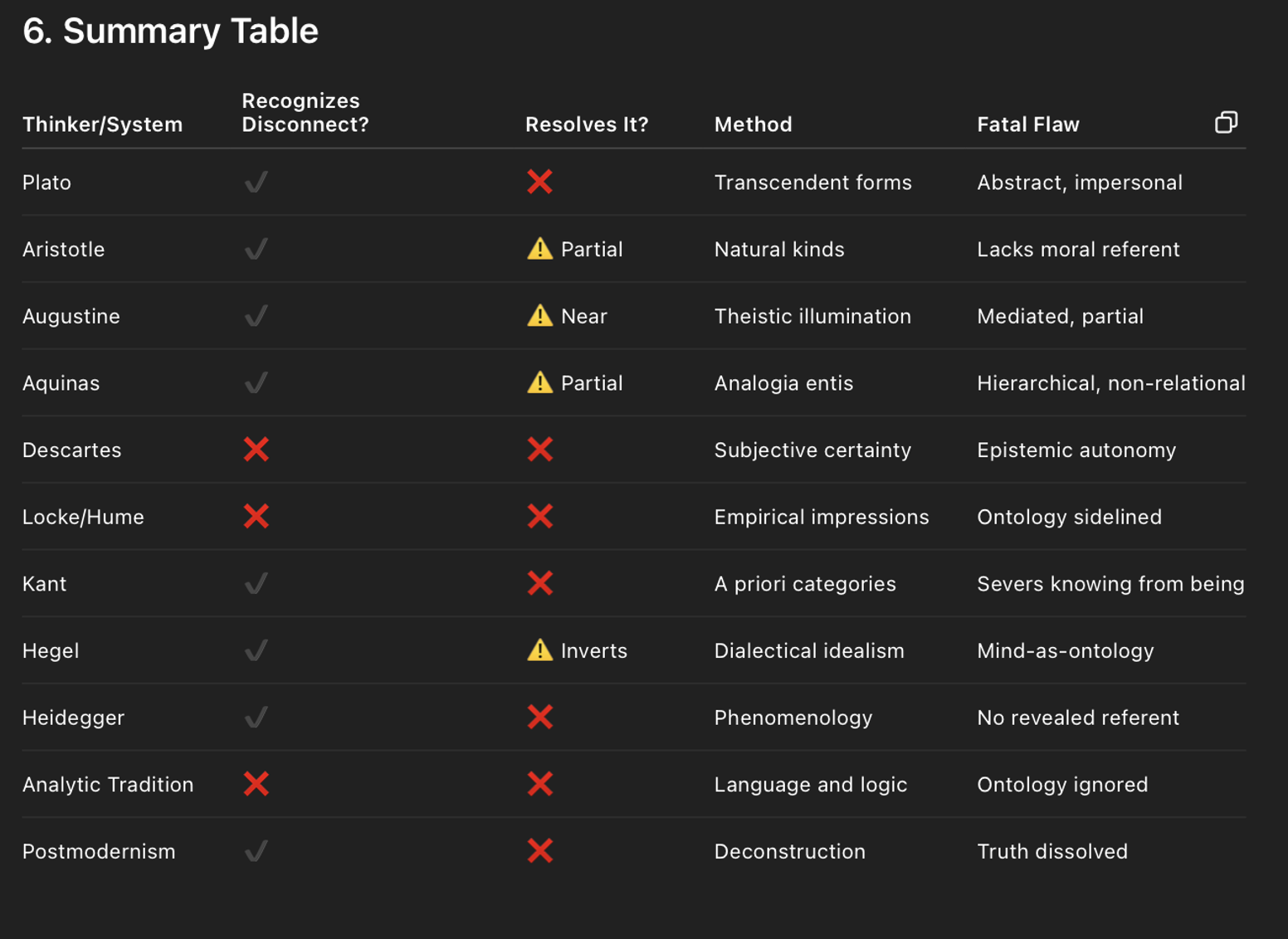

Having established above that truth is an ontological kind, and that its suppression is both morally evasive and logically fallacious, this second section tracks how that suppression unfolded historically. We map the thinkers and systems that either identified, denied, or deformed the relationship between being and knowing.

This is not a historical survey for its own sake—it is an exposure of philosophical drift, and a demonstration that no system outside of relational ontology has successfully resolved the fracture.

Plato Forms: Disembodied Universals Without Covenant

Plato posited that ultimate reality resides in a realm of immutable, perfect Forms—abstract universals that transcend the material world and give it structure. While this introduced an ontological hierarchy, it was ungrounded in relational or moral reality. These Forms existed independently of creation, covenant, or Creator, rendering “truth” an ideal to be apprehended intellectually, not encountered relationally. Thus, the Platonic model foreshadowed ontology as prior to epistemology but severed it from divine confrontation, moral obligation, or historical self-disclosure. In Scripture’s terms, the Logos is not merely a Form—it is a Person who speaks, convicts, and invites. Plato's ontology lacked this covenantal voice.

Aristotelian Essences: Immanent Structures Without Moral Invitation

Aristotle relocated the Forms into the things themselves—asserting that every entity has an essence (its whatness) and a purpose (its telos). This preserved ontological primacy but confined it to immanent categorization rather than transcendent disclosure. His system offered a world ordered by cause, kind, and finality, yet it remained morally inert. There was no divine prerogative to instantiate being, no relational summons to alignment—just a rational taxonomy to be analyzed. Aristotle refined ontology but failed to recover revelation. His model reduced participation in truth to philosophical classification rather than obedient reception of a moral reality.

Augustine

Aquinas’ Scholastic Digression:

Institutionalizing Ontology Through Essence and Grace, from Submission to Institutional Leverage

Aquinas systematized Aristotelian metaphysics within a Roman ecclesiastical structure, recasting divine ontology into scholastic categories—essence, act, and infused grace. While affirming the primacy of being, he transformed relational submission into institutional leverage: access to God became mediated not directly through the convicting Spirit or revealed Word, but through sacramental economy, clerical authority, and metaphysical constructs. Ontology was retained, but its relational immediacy was displaced. In place of prophetic confrontation came sacerdotal distribution; in place of covenantal fidelity, ecclesial taxonomy. The truth remained conceptually exalted but was no longer existentially accessible without sanctioned intermediaries.

Descartes

Locke / Hume (Empiricism)

Kant’s Onto-Epistemic Rupture: Reason’s Sovereignty Over Revelation

Kant's project can be read as a philosophical reaction to this institutional overreach. In seeking to preserve human moral agency from theological absolutism and metaphysical speculation, he severed the link between ontology and cognition. Epistemology, for Kant, was no longer a response to being—it was a filter imposed upon it. His categories of understanding replaced divine self-disclosure with subjective schemata. What had once been relationally encountered as truth was now cognitively domesticated. While Kant intended to safeguard freedom and reason, he inadvertently placed the knowing subject above the known reality—thus completing the rupture that made moral alignment optional and ontological submission nearly unintelligible.

German Idealism (Fichte, Hegel)

Heidegger

Analytic Philosophy

Postmodernism (Derrida, Foucault)

Each of the above systems either:

None of them restore:

II.H. Conclusion

II.H. Conclusion

The history of philosophy shows not an unbroken line of insight, but a progressive suppression and evasion of the ontological root of truth. Even the best attempts remain abstract, hierarchical, or impersonal.

The relational-ontological model resolves what they could not—by returning to the only place such a reconciliation is possible: Not in reason, but in revelation. Not in system, but in submission. Not in abstraction, but in the person of Christ, who is truth.