Art is often treated as a cultural barometer—a vivid record of a civilization’s tastes, technologies, anxieties, or political convictions. Historians may trace stylistic developments as consequences of shifting patronage, ideology, or academic convention. Yet beneath the visible surface of brushstrokes, iconography, and form, there lies a more fundamental diagnostic: art as an ontological echo—a visual record of a people’s moral and relational posture toward truth itself.

This essay contends that historical art movements are not primarily engines of change but lagging indicators of deeper moral and metaphysical drift. Artistic production does not initiate rebellion or repentance. Rather, it reveals what has already occurred in the soul of a people—their linguistic realignment, mythic substitutions, semiotic reframings, and above all, their relational distance from the Creator. Art is the fruit, not the root.

To interpret this cultural fruit, we offer a framework grounded in relational ontology—the belief that all being and meaning emerge from right relationship with God. Within this frame, history does not unfold merely as progress or decline, but as a pendulum motion between moral extremes. Yet this pendulum does not swing flatly; it spirals, with each arc revealing both a change in direction and a change in distance. It moves between poles—such as Puritan restraint and Epicurean indulgence—but also draws nearer to or farther from a fixed moral apex: the transcendent source of value and beauty in the divine nature itself.

The further a culture spirals from this apex, the more its art begins to show symptoms of dislocation. Symbol detaches from substance. Beauty becomes self-referential or sentimental. Form no longer serves transcendent meaning but indulges autonomous sensation or ironic distance. This degradation is not linear, nor always immediately visible. But at a macro scale, the arc of cultural aesthetics reliably shadows the soul’s drift.

While this essay concentrates on the Western tradition, this is not an arbitrary bias but a theological necessity. The West uniquely received the relational structure of biblical revelation—first through the Hebrew Scriptures, then through the apostolic witness to Christ, and later through integration into Greco-Roman symbolic systems. Thus, the Western canon provides the clearest narrative arc of ontological submission, rebellion, reformation, and symbolic reverberation.

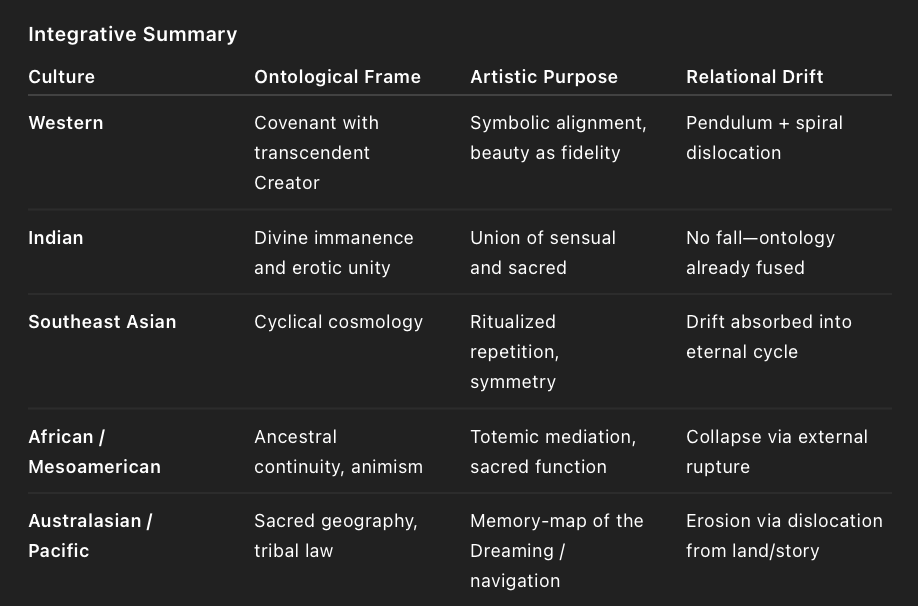

Other civilizations, by contrast, express different ontological grammars. In the Indian subcontinent, temple carvings often convey an immanent and erotic metaphysic, where the sensual is not morally transgressive but spiritually fusive. In Southeast Asia, the symbolic systems of mandalas and cosmic reliefs reflect cyclical, not covenantal, cosmologies. In pre-modern Africa and the Americas, art tends to mirror ancestral, animistic, or totemic structures, where aesthetic power emerges from participation in nature or spirit realms, rather than from submission to a transcendent Creator.

These contrasts are not about aesthetic sophistication, but about ontological anchoring. The art of a people reveals not just what it values, but where it stands in relation to the divine source of all value.

This essay therefore offers a macroscopic, theological reading—a relational-ontological dislocation analysis. It is not concerned with granular technique or individual genius. Rather, it traces the civilizational-level motion of cultural imagination: the long swings, the slow spirals, the silent severances.

We begin by defining the spiral-pendulum model. From there, we examine how the major artistic movements in the West—mapped over time—reveal a progressive drift, interrupted by occasional moments of return. Then, we explore what signs precede these aesthetic shifts: the leading indicators embedded in language, law, and myth. Finally, we widen our lens to compare other cultural ontologies before closing with the moral implications for creation, perception, and worship.

Art does not lead rebellion or return. But it does reveal where we have already gone.

To understand how art serves as a cultural diagnostic, we must first clarify the model this essay uses to interpret historical motion—not simply as a sequence of events, but as a pattern of relational realignment or dislocation. That model is a pendulum—but not one that swings in a single, flat arc. Instead, it spirals, tracing not only movement between opposing moral postures, but also distance from an unchanging moral apex.

At the simplest level, cultures tend to swing between two broad poles:

Puritanism: restraint, moral seriousness, symbolic integrity, and vertical accountability.

Epicureanism: indulgence, sensual autonomy, symbolic fragmentation, and horizontal immediacy.

These are not references to historical Puritans or Epicureans, but to enduring moral archetypes. The Puritan pole represents fidelity, restraint, and a posture of reverence toward transcendent truth. The Epicurean pole reflects autonomy, immediacy, and a focus on sensuous experience.

This is a diagnostic axis, not a historical judgment. It does not critique specific traditions or figures, but offers a model to trace the ethical posture embedded in a culture’s dominant artistic expressions. Where Puritan alignment emphasizes order and symbolic coherence, Epicurean drift privileges novelty, pleasure, and aesthetic self-expression.

These poles give us a framework to map the ethical mood of an era’s art—whether it leans toward submission or autonomy, coherence or fragmentation, transcendence or immediacy.

* Note on Terminology:

The use of “Puritan” and “Epicurean” in this essay does not refer to strict historical categories or formal philosophical schools, but rather to enduring moral archetypes. The Puritan pole denotes transcendent accountability, symbolic integrity, and covenantal restraint; the Epicurean pole denotes sensual autonomy, immediacy, and symbolic looseness. These terms are not used to evaluate specific historical traditions, but to map the ethical posture embedded in artistic movements as cultures drift nearer to—or further from—a fixed moral apex. While this framing borrows conceptual resonance from historical Puritan theology and Epicurean philosophy, it is employed here as a diagnostic tool, not a historical judgment—comparable in spirit to the ethical contrasts seen in C.S. Lewis’s The Abolition of Man, T.S. Eliot’s Notes Toward the Definition of Culture, and Alasdair MacIntyre’s After Virtue. The terminology also echoes its cultural use in writers like Salman Rushdie, who has invoked the Puritan–Epicurean dichotomy to describe the clash between imaginative freedom and moralistic repression. Here, however, the axis is not deployed rhetorically or politically, but ontologically—as a lens for tracking how artistic expression reflects a culture’s nearness to, or rebellion from, relational truth.

Yet history does not merely oscillate between these two poles. The pendulum’s rope is not of fixed length. With each swing, the distance from the moral apex may increase or decrease. This introduces a second dimension: ontological proximity or dislocation.

A culture may indulge, but still carry symbolic weight and covenantal memory (e.g., Baroque theatricality).

Or it may restrain itself with severe formality but sever its connection to transcendent reference (e.g., Neoclassical rationalism).

Thus, the real concern is not merely the direction of the swing, but the distance from the apex—the source of meaning, proportion, and ontological order, as revealed in the relational character of God.

In this model:

The apex is fixed: the holiness, beauty, and truth of God as ontological source.

The swing reflects a culture’s dominant moral posture (toward purity or pleasure).

The spiral radius indicates the depth of ontological drift (alignment vs. autonomy).

Together, these motions form a three-dimensional pattern—a swinging spiral, not a flat arc. And art, as we will see, traces this trajectory with remarkable fidelity.

As the spiral widens, art begins to exhibit signs of semiotic entropy:

Symbols lose their referents.

Forms no longer correspond to higher orders.

Beauty becomes either ornamental or ironic.

Meaning collapses into sensation or performance.

Yet these signs do not appear immediately. The spiral drift is first felt in language, law, education, and liturgy. Only later do we see the visual aftermath: in paintings, architecture, and sculpture. That is why art functions as a lagging indicator—it reflects the settled state of things, not their incipient cause.

What follows, then, is not an artistic chronology for its own sake, but a reading of art as a mirror to relational reality—a delayed echo of a people’s movement toward or away from their source.

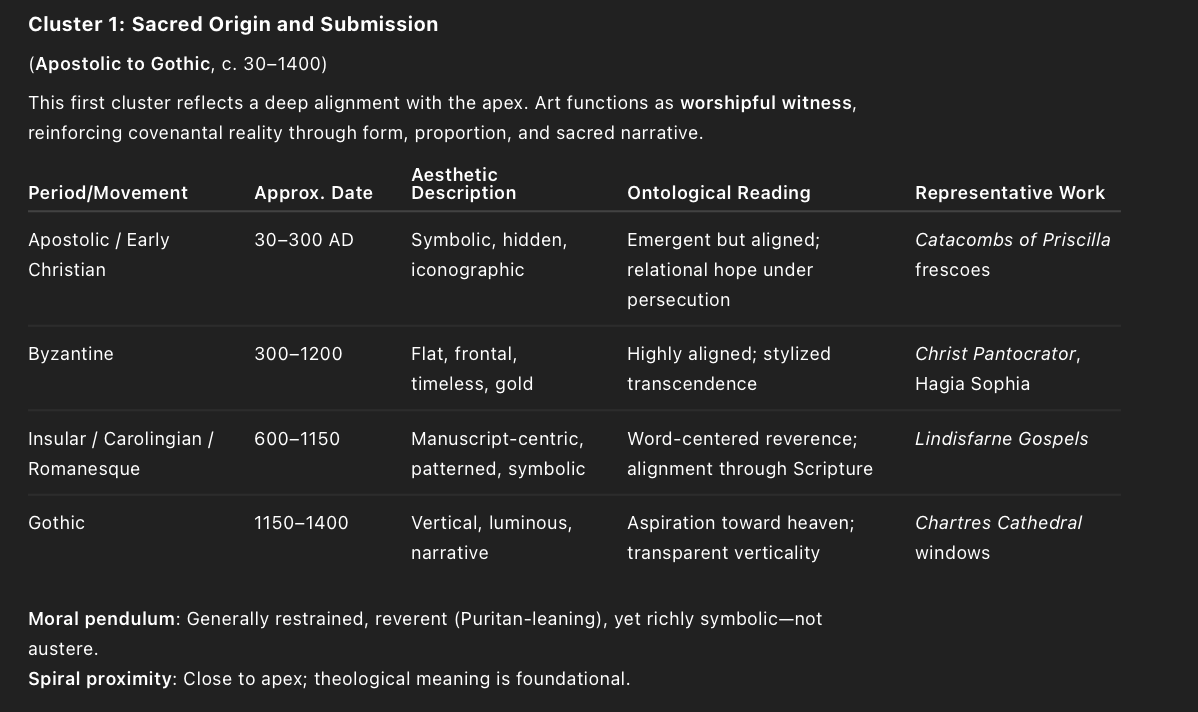

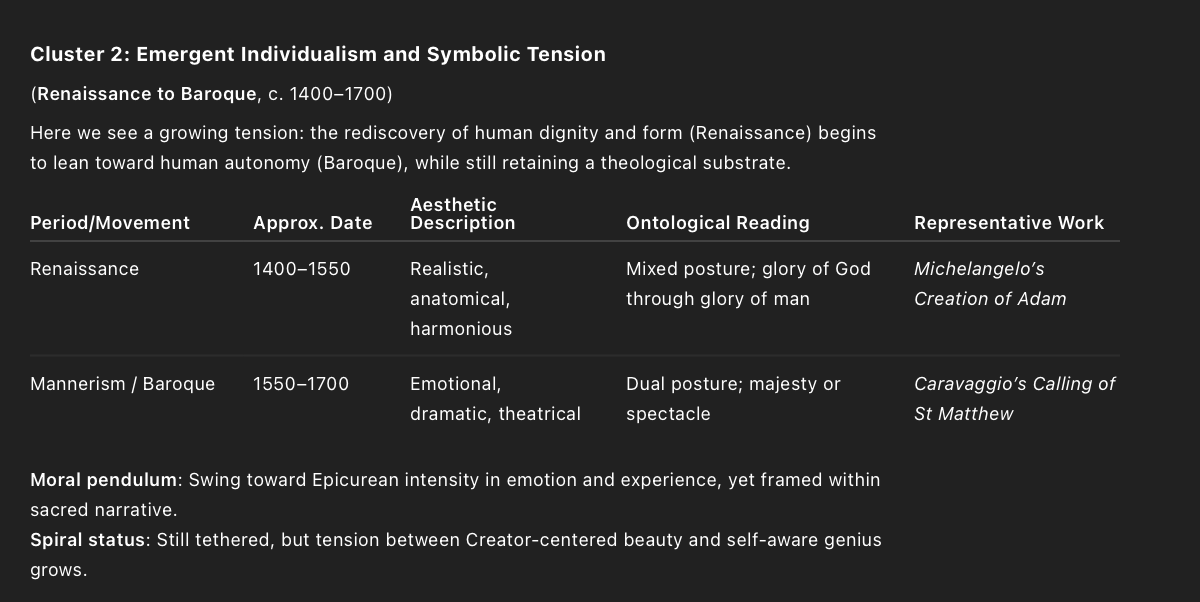

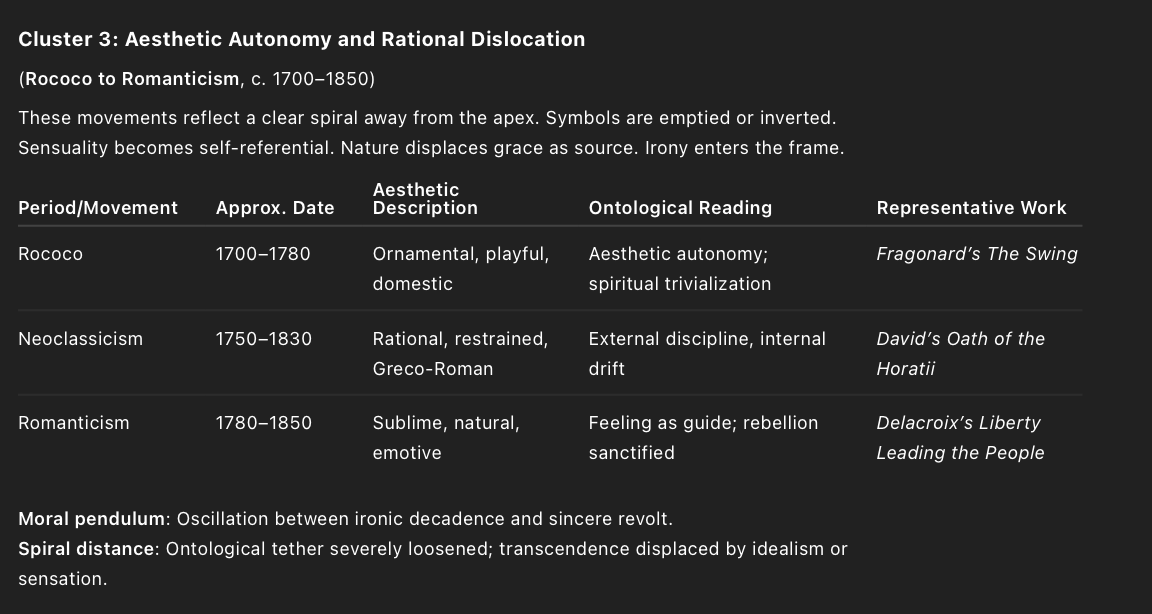

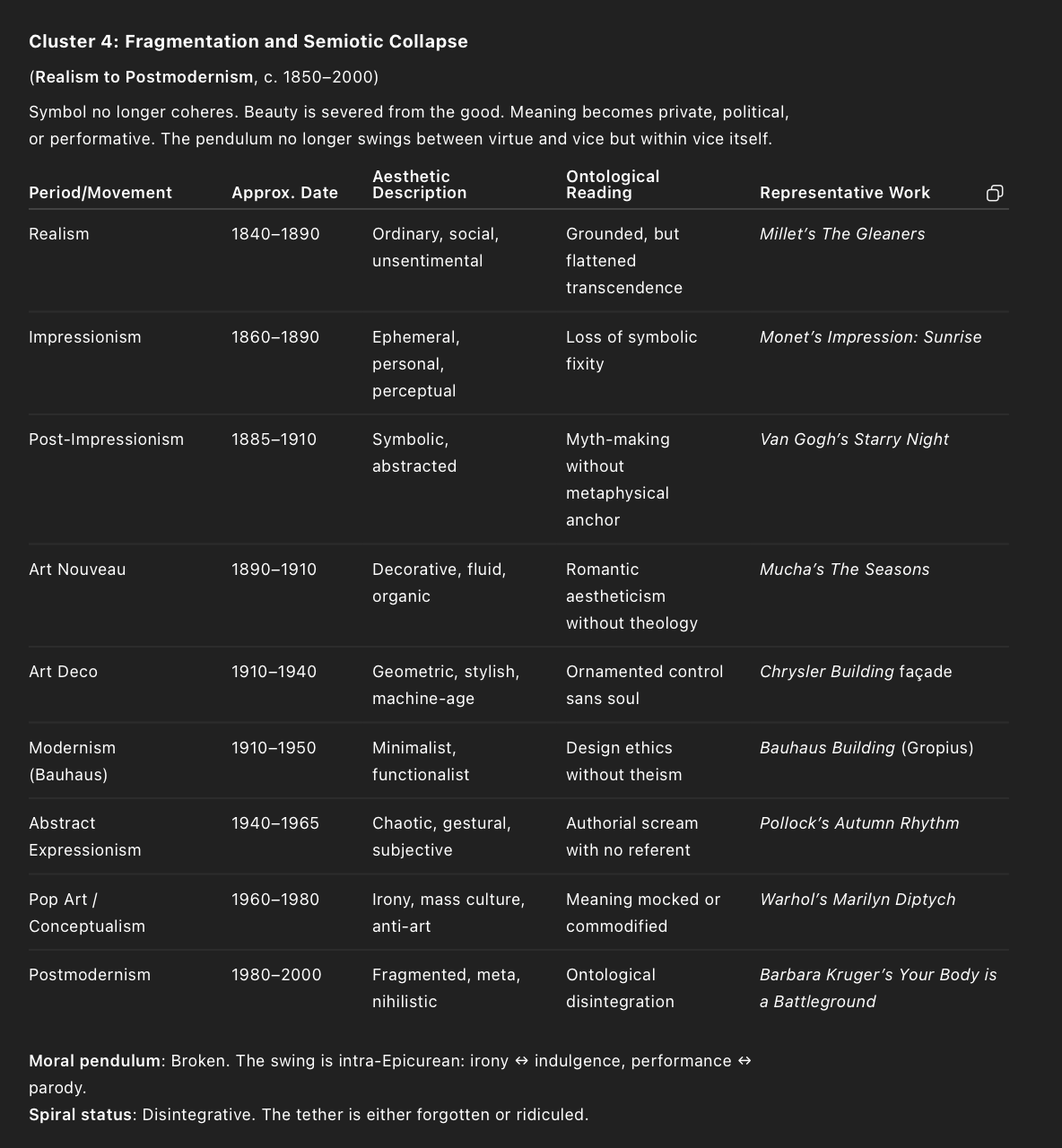

The following table offers a macroscopic survey of the major artistic movements in the Western tradition, arranged along the axis of relational alignment. It does not aim to document every regional nuance or sub-genre, nor to capture the individual brilliance of particular artists. Rather, it presents a civilizational-level pattern—a sequence of aesthetic phases that echo broader moral swings and ontological spirals.

For each movement, we provide:

Approximate date range,

Stylistic descriptors,

A relational-ontological dislocation reading,

And a representative artwork, to give visual grounding.

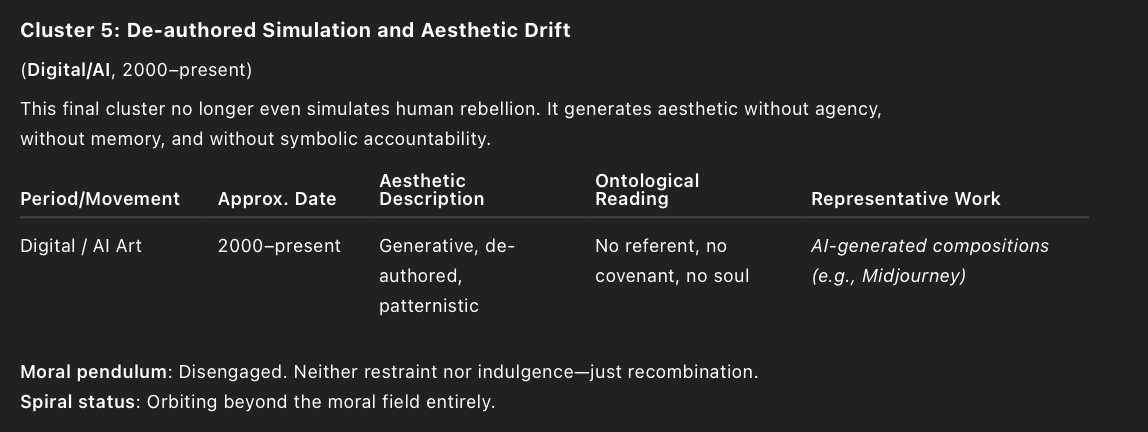

This survey is structured into five thematic clusters, each reflecting a distinct phase in the relational arc of Western art.

Having surveyed the major artistic movements in the Western tradition, we now observe a pattern beyond stylistic shifts: a moral and ontological spiral. The pendulum does not simply swing between restraint and indulgence; it widens, stretches, and accumulates. Each aesthetic phase bears the residue of the last, but loosens its tether to transcendent reference.

This spiral motion becomes most evident after the Renaissance, when Christian theology begins to lose its role as the governing reference point:

Baroque seeks to exalt divine majesty (Puritan pole), but veers toward theatrical excess (Epicurean drift).

Rococo indulges in decorative sensuality (Epicurean swing).

Neoclassicism reins in the aesthetic with rational order (Puritan correction).

Romanticism rebels with passion, nature-worship, and expressive interiority (Epicurean release).

Realism sobers the frame with moral weight (Puritan lean).

Impressionism dissolves form into perception (Epicurean loosening).

Modernism strives for ethical design (Puritan reach).

Postmodernism collapses into irony, parody, and fragmentation (Epicurean collapse).

Digital and AI-generated art no longer swings—it floats: de-authored, untethered, without memory or covenant.

This trajectory is not linear. Romanticism echoes Neoclassical form; Pop Art mimics Modernist minimalism but inverts its moral weight. Over time, the pendulum poles themselves lose coherence. Eventually, the culture no longer swings between order and rebellion, but drifts within autonomous errors—irony without reverence, indulgence without joy, fragmentation without grief.

The spiral no longer traces return. The rope has lengthened. The center no longer holds. This aesthetic entropy marks not just decline, but delay. For all its noise and novelty, art rarely leads. It gestures, reflects, and memorializes—but only once the drift has already settled into form. To understand this pattern, we must turn to art's temporal role as a lagging indicator of deeper ontological transformation.

Art does not lead ontological transformation; it follows it. It does not create new realities but rather ritualises and reflects them once they have already taken hold. Before any serious investment in the arts can take place—whether visual, architectural, literary, or liturgical—three conditions must converge within a society: geopolitical stability, economic sufficiency, and what may be called an attentional surplus.

Geopolitical stability means that the society is not in existential turmoil. It may be in moral or philosophical crisis, but it is not, in that moment, disintegrating at the structural level. Economic sufficiency ensures that resources exceed mere subsistence, allowing time, materials, and patronage to be directed toward symbolic or aesthetic activity. And attentional surplus refers to the deeper cultural bandwidth—moral, cognitive, and spiritual—that allows a people to turn their focus toward meaning, beauty, or critique, rather than being consumed by survival, vigilance, or immediate response. In this framework, attentional surplus roughly corresponds to a form of axiological–deontic–modal headroom: space to contemplate what is good, what must be done, and what is possible beyond necessity.

Without these conditions, art cannot function as a reflective instrument. It simply cannot emerge. Historically, this is why the great artistic periods do not typically arise in moments of chaos, but in the seasons that follow conquest, consolidation, or civilizational cohesion. The art may later criticise that order—but it requires the order first to even exist.

Once those preconditions are met, art begins its proper function—not as a catalyst, but as a codifier. Ontological drift begins silently, in categories and presuppositions. It migrates through language, ethics, and the recalibration of social myths. Art does not cause this drift. It arrives later, to encapsulate it—to give visual, symbolic, or poetic form to what has already become tacitly accepted. That encapsulation is always retrospective. It reflects what is now assumed—not what is being actively contested. For this reason, art is by nature a lagging indicator of cultural transformation.

This delay is especially visible in moments of major civilizational transition. While the philosophical or theological consensus is still in flux, artistic production tends to fragment: its reference points are unstable, its gestures ambiguous, its symbolism either ironic or uncertain. But once the drift congeals into myth—once a new moral and ontological order becomes normalized—art begins to mirror that stability. Whether in the form of iconostasis, propaganda murals, satirical literature, or minimalist design, art declares that the new myth has arrived, and is here to stay.

Occasionally, artistic flourish emerges even in times of broader scarcity—but this almost always occurs under conditions of localised stability or elite concentration of surplus. The Renaissance in Florence unfolded during intermittent turbulence, but the Medici concentrated enough political protection and economic wealth to create a functional zone of attentional surplus. Even in times of war or disorder, if the ruling class can offload risk and control narrative, a cultural bloom may occur in isolated pockets. But these remain exceptions that confirm the broader rule: art follows peace—or at least the impression of internal peace.

In the contemporary world, this impression can now be simulated. Modern media and narrative management introduce a new complication: the conditions of surplus—and of crisis—can be manufactured. Internal peace may be projected through consumer calm and market stability, even while the moral and ontological core of society is collapsing. Alternatively, a sense of perpetual threat may be generated by amplifying distant wars, foreign unrest, or abstract existential risks, even when the local conditions remain functionally peaceful.

This creates a distortion: art still lags, but now it may lag behind a false signal. It may reflect what a society believes itself to be enduring rather than what is ontologically true. This produces entire aesthetic movements centred on simulated crisis, manufactured exhaustion, and performative resistance—none of which require an actual collapse, only the perception of one.

So while the temporal logic remains intact—art still follows drift—the referent has become unstable. In previous eras, art reflected a real, if corrupted, consensus. In the current era, it may mirror a narrative spiral that is neither real nor honest—merely effective.

Having established why art necessarily lags behind cultural transformation, the next section will trace how this delay unfolds across the major artistic movements of the Western tradition—from classicism to modernity to the semiotic chaos of the present.

In this way, art performs a backward-looking function: it confirms what has already taken hold beneath the surface. But not all cultural expressions are retrospective. Some signals point forward—surfacing in the midst of flux, revealing drift before it settles. It is to these leading indicators that we now turn.

If art is the echo, what sets the stage for the sound? If artistic movements are the visible aftershocks, what fault lines form beforehand? This section explores the leading indicators—the cultural shifts that precede and predict aesthetic dislocation. Chief among these are the slow, often imperceptible drifts in language, law, liturgy, and myth. These changes initiate the moral and metaphysical pendulum swing long before brush meets canvas or stone meets chisel.

The Overton Window—the conceptual space of what is publicly thinkable or sayable—offers a useful diagnostic. Within every culture, certain ideas are unthinkable, others debatable, others mainstream, and finally normalized. Over time, the window shifts, pushed not by reason alone, but by subtle semiotic engineering: how words are redefined, stories are reframed, and symbolic associations are gradually decoupled from their moral referents.

At the outset of cultural drift, new codes are introduced—semantic pivots that alter the emotional or moral valence of key terms. Words like tolerance, freedom, identity, or justice become semiotically plastic. Their biblical or covenantal roots are severed, and new uses are encoded with latent inversion. What once signaled submission to divine order now signals emancipation from it.

This is followed by the planting of new myths—cultural narratives that reinforce these altered codes. These myths are not always fictional; they are lived stories, often expressed in slogans, school curricula, film, and advertising. They elevate the self, normalize rebellion, sentimentalize transgression, or romanticize fracture. At this stage, art has not yet changed. But the soil beneath it is shifting.

As these new codes and myths embed themselves in cultural consciousness, they begin to alter institutions—legal frameworks, educational systems, even ecclesiastical liturgies. What was once a theological confession becomes a negotiable statement. What was once an immutable ordinance becomes an evolving social contract.

This is the point at which epistemology collapses into anthropology—truth is no longer revealed, but assembled; not discovered, but negotiated. And from this anthropocentric epistemology comes the aesthetic inversion we later observe in visual art.

These shifts do not occur overnight. The cultural pendulum does not swing because someone pulls a rope. It swings because the tether is gradually lengthened—through language, myth, law, and liturgy—until the center of gravity itself is displaced. Then, and only then, does the art reflect what has already become normalized.

Art does not move the window. It appears after the frame has shifted.

While this essay has focused on the Western tradition—tracing its aesthetic journey from sacred orientation to semiotic collapse—it is worth briefly broadening the frame. Other civillizations have also produced extraordinary artistic legacies, often long before or independent of Christian influence. These traditions deserve recognition not just for their technical achievement, but for the ontological frameworks they reflect.

This comparative detour does not serve to assert Western superiority. Rather, it aims to sharpen the theological lens: to show how the meaning of art is inescapably tied to what a culture believes about God, being, time, and truth.

Classical Hindu art, particularly temple sculpture, reflects a deeply immanent metaphysic. Gods and goddesses are not distanced from creation but interwoven into its sensual and symbolic fabric. Erotic imagery—abundant in temples like Khajuraho—is not meant as scandal or rebellion, but as sacred fusion. The transcendent/immanent divide central to biblical ontology is not preserved. Thus, aesthetic sensuality is not ontological drift, but theological expression.

Yet this also means that art in these traditions does not display a “fall” from covenantal tether, because it was never tethered to a transcendent moral apex. Symbolic correspondence is not lost; it was never defined in those terms. The pendulum model does not apply in the same way, because the vertical axis is structurally absent.

In regions shaped by Buddhism and syncretic animism, art frequently encodes cyclical cosmology. Mandalas, bas-reliefs, and stupa carvings depict not historical movement but eternal return—patterns of being, not covenants of becoming. The art is intricate, meditative, and often symbolic, but it does not presuppose a moral apex outside the cycle. Relational fidelity—in the biblical sense—is not the governing grammar.

As a result, aesthetic dislocation in these contexts does not follow the same spiral. There may be shifts in technique, but there is no equivalent “symbolic collapse” because symbolic anchoring is already diffused into the cycle. Disintegration is not deviation; it is absorbed into the turn of the wheel.

In many traditional African and indigenous American cultures, art serves as a vessel of ancestral presence or spiritual continuity. Masks, totems, textiles, and ritual objects are not primarily visual expressions, but functional mediators of unseen forces—be they nature spirits, tribal archetypes, or ancestral energies.

Here, ontology is participatory—identity is bound to the tribe, the land, and the ancestral past. Artistic collapse, then, often arrives through external imposition (e.g. colonization, industrialization), rather than internal symbolic drift. When art dislocates, it is because the relational matrix—tribal, territorial, or spiritual—has been disrupted, not because symbolic language has unraveled from within.

In the Aboriginal cultures of Australia and the many island societies of Polynesia, Melanesia, and Micronesia, art is fundamentally interwoven with land, ancestry, and sacred story. This is not art for contemplation or critique. It is art as embedded memory, often inseparable from oral tradition, ritual function, or geographic embodiment.

The visual tradition of dot painting, rock etching, and ceremonial body design reflects the cosmology of the Dreaming (Tjukurpa)—a sacred, eternal layer of meaning believed to underlie the physical world. The Dreaming is not history or myth in the Western sense, but a metaphysical reality that continues to structure identity, land, law, and kinship.

Art is thus ontologically functional: it maps spiritual geographies, marks clan totems, and communicates memory across generations. There is no binary between sacred and secular, nor between symbol and land. But neither is there an external apex—truth is not revealed from beyond, but emerges from within the cosmological ground of the tribe and land.

From the carved tiki figures of Māori and Hawaiian cultures, to tapa cloth patterns in Tonga and Samoa, to the sacred navigation stick charts of Micronesia, these art forms are deeply tribal, relational, and ecological. They express continuity with gods, ancestors, and natural forces—not through imitation or narrative, but through rhythmic abstraction, repetition, and embodied ritual.

In both Polynesia and Aboriginal Australia, art carries sacred weight, but it is not designed to express ontological verticality. The transcendent–immanent divide does not function theologically. Art is ancestral, topological, cosmic, but not covenantal.

In cultures without a transcendent Creator, art does not rebel—but neither can it repent.It anchors, it remembers, it mediates—but it does not return to a Source beyond itself.

This comparative overview strengthens the essay’s central claim: that art is not simply aesthetic, but ontological testimony. And it makes clear that the unique drift in Western art is not due to aesthetic failure, but relational betrayal—the loss of covenantal alignment with the One who defines both form and meaning.

These traditions show that ontological misalignment takes many forms. In the West, where truth was once revealed by a personal, transcendent God, aesthetic drift appears as a betrayal—as a fall from correspondence. In cultures where ontology is cyclical, immanent, or animistic, collapse is less visible, not because it does not occur, but because symbol never stood on transcendent ground to begin with.W hat is lost in the West is symbolic covenant. What is absent elsewhere is symbolic transcendence.

This, again, reinforces the need for a theological reading of art history. For it is not technical brilliance, emotional resonance, or historical longevity that makes art significant—it is the ontological claim it either reflects or obscures.

This essay has necessarily focused on the Western tradition—not because of aesthetic preference or colonial impulse, but because the West uniquely received, and for a time retained, the theological scaffolding required for ontological correspondence. Through the Hebrew Scriptures, apostolic transmission, and Greco-Roman integration, Western art was—at its best—an echo of covenantal reality.

But this is not a claim of artistic or cultural superiority. It is a statement about ontological posture.

The West is not “greater” because its cathedrals were taller, nor are non-Western cultures “lesser” for working in wood, sand, dye, bronze, or rhythm. The issue is not the material, but the referent.

Only biblical ontology demands that beauty correspond to truth, and that symbol remain accountable to transcendent reality.

Where that theological grounding is absent, art may still flourish in power, intimacy, or symbolism—but it does not reveal holiness. It may point to sacred continuity, ecological balance, or spiritual awe, but it will not confront rebellion, or restore broken relationship with a Creator outside the created order.

Many cultures remember spirit, ritual, tribe, and cosmos. But where the Creator is not ontologically distinct, and where truth is not relationally accountable, beauty cannot heal. It cannot judge or redeem.

Thus, the critique here is not of artistic technique, nor even of spiritual sincerity. It is a diagnosis of ontological drift: a reading of whether a civilization’s art remains tethered to the relational truth that alone makes symbol meaningful.

Art does not lead rebellion, nor does it initiate revival. It does not invent our gods or our ghosts. But it does remember them. It reflects them. It reveals, with remarkable honesty, where we have already gone.

Throughout history, the dominant artistic forms of each age have borne witness to that age’s relational posture—whether aligned with the transcendent source of truth, or drifting from it in pursuit of autonomy, sensation, or abstraction. These movements are not random. They trace the arc of a pendulum, swinging between Puritan clarity and Epicurean fragmentation. But the pendulum does not simply swing—it spirals. Each oscillation may bring us not just to the opposite moral pole, but further out from the fixed center of divine relational order.

This is why art matters—not because it decorates our walls or fills our museums, but because it testifies to our ontology. It tells us whether our symbols still carry weight, whether our beauty still corresponds to goodness, whether our form still submits to truth.

And because art is a lagging indicator, it is never our first warning. By the time the canvas distorts the image, the language has already shifted, the myths have already turned, and the laws have already bent. The spiral has already widened. The pendulum has already swung.

But if we learn to read the signs—not only in what is painted, but in what is no longer possible to paint—we may still trace our path back.

Not all is decay. Even in dislocation, remnants remain. Even amid abstraction, fragments of longing persist. The way back is not through aesthetic nostalgia or cultural preservation, but through relational realignment—a return to the fixed moral apex from which all meaning flows: the holy, covenantal, personal God.

To discern art is to discern a people’s ontology. And to discern that is, in part, to discern our own.