Economics, in its conventional definition, is the study of how scarce resources are allocated among competing wants. But this seemingly neutral definition conceals a metaphysical stance: that scarcity is a universal constant, that human desires are authoritative, and that value is constructed, not revealed. Beneath its mathematical rigor and policy debates, modern economics operates on an implicit theology—one that assumes human autonomy, material sufficiency, and systemic management as the default ground of human flourishing.

This essay challenges that foundation.

From an ontological standpoint, economics is not a merely technical field; it is a moral theatre. Scarcity is not a metaphysical law but a post-fall (post-lapsarian) condition—a distortion of the abundant order originally established by God. Human desires are not sovereign indicators of value but are themselves subject to judgment. And the distribution of goods is not a neutral function of supply and demand, but a diagnostic of deeper truths: relational alignment, divine trust, and moral posture.

At its root, economics is axiological—it begins with a definition of what is good. This then unfolds into deontology—a sense of duty and relational obligation—and finally into modality—the choices and systems by which resources are distributed and acted upon. This triadic structure (axiology → deontology → modality), already foundational in the broader Submetaphysics' framework, recasts economics not as a self-contained discipline but as a downstream expression of ontological alignment.

This has radical consequences for how we interpret economic systems. Modern schools of thought—from classical liberalism to Marxist redistribution, from behavioral nudging to ecological limits—all offer competing visions of human worth, responsibility, and purpose. But rarely are these visions made explicit. We must learn to distinguish between surface-level mechanisms and the hidden anthropological and theological postures embedded in every economic framework.

This essay proceeds in six parts:

We begin by exposing the assumptions—often unacknowledged—that shape secular economics, particularly its view of human nature, scarcity, and progress.

We then offer a taxonomic overview of key economic systems, applying an ontological filter to discern their implicit moral architectures.

From there, we examine the practice of tithing—not as ritual, but as an ontological act of acknowledgment and alignment.

The fourth section establishes the non-transferable moral responsibility of the individual to act economically in relation to the vulnerable—grounded in Genesis 4, Luke 10, and Matthew 25.

The fifth section explores what economics looks like within the Kingdom of God—where scarcity is abolished, but stewardship is eternal.

Finally, we conclude with a structured contrast between secular and biblical economic frameworks—demonstrating not merely a different ethic, but a different ontology of wealth, worth, and reward.

Throughout, the analysis draws on the relational-ontological paradigm laid out in the Submetaphysics' framework, which insists that truth is not merely descriptive but relationally revealed, and that every economic act is an act of either alignment or rebellion.

Economics is not merely the management of scarcity—it is the stage on which moral beings are tested. And until this is seen, no system—however just it may seem—can be trusted to reflect the order of the Kingdom.

Every economic system—whether it claims neutrality or not—rests upon an implicit anthropology. It assumes something about what human beings are, what they desire, and how they are to relate to one another and to the world. The modern economic imagination, however varied in its branches, is largely rooted in a post-Enlightenment humanism that treats man as autonomous, scarcity as natural, and progress as inevitable. This section will unpack these assumptions, contrast them with the biblical framework, and expose the ontological inversion that underlies them.

Three foundational assumptions shape most secular economic systems:

The human being is viewed as a self-defining, preference-expressing unit. Desires are treated not as morally weighted or spiritually significant, but as sovereign indicators of utility. The consumer is king—not because he is virtuous, but because he is autonomous. In this model, there is no obligation to evaluate whether a preference is rightly ordered. Value is subjective and emergent.

This, in effect, makes economics morally agnostic. It cannot ask whether a good ought to be desired; it only tracks that it is. A factory producing pornography or weapons may be economically “efficient” so long as demand is met. The ontological weight of goods and intentions is erased.

Scarcity is presumed not as a result of rebellion or disorder, but as an ontological fixture of the cosmos. Human history is therefore viewed as a struggle against lack—an effort to stretch limited means to meet unlimited wants. This leads to either utilitarian calculus (maximize output) or zero-sum assumptions (compete for limited shares).

In this view, abundance—where it occurs—is an anomaly, a momentary exception, or a privilege. It is never seen as a theological norm disrupted by sin. Thus, the secular model enshrines a worldview in which deficiency, not divine provision, becomes the natural state of creation.

Economic advancement is measured almost entirely in material terms: increased productivity, higher consumption, technological expansion. GDP, stock market performance, and productivity gains are celebrated without reference to moral outcome or spiritual formation.

Even systems that speak of equality or justice often define success in materialistic terms: redistribution of wealth, parity of access, or elimination of poverty—but not necessarily in alignment with divine purpose, personal accountability, or covenantal stewardship.

Together, these assumptions result in what may be called an ontological inversion: economics becomes not the outflow of a moral order, but the arena in which humans construct meaning. Desire precedes duty. Survival precedes worship. Production precedes praise.

The biblical framework offers a diametrically opposite anthropology, in which economy is a test of alignment, not a neutral arena of exchange. In this model, three principles govern all economic participation:

God alone declares what is good. Value is not constructed by aggregate desire but revealed by the Creator. The imago Dei grants intrinsic worth to persons, not based on output or efficiency, but by divine decree. Goods are good insofar as they align with God's purposes; desires are valid only if they correspond to rightly ordered love.

This axiological primacy means that economics cannot be neutral: every transaction either honors or subverts the revealed hierarchy of value.

Once value is revealed, duty follows. The relational nature of creation—God to human, human to neighbour—imposes obligations. The command to love one's neighbor as oneself is not economically optional. The duty to care for the widow, the orphan, and the stranger is not an act of private charity—it is a covenantal mandate.

In this light, questions of distribution are not merely political or structural. They are moral assignments—each person is accountable for the right use of what he has been given, within the network of relationships God has established.

The method of economic action—whether investing, giving, building, or withholding—must flow from faithful stewardship, not autonomous calculation. The biblical view treats every resource as a test of trust, not as a tool for self-advancement. Wealth is not evil, but it is always expository: it reveals the posture of the heart toward God and neighbor.

In this model, the modality of economic behavior (how we act) is shaped not by efficiency or strategy, but by fidelity to God’s revealed order. This includes both material decisions and the noetic framework in which those decisions are interpreted.

The doctrine of the fall provides the theological basis for the presence of scarcity, but not its glorification. Scarcity is real—but it is a symptom, not a structure. It serves a diagnostic function: it reveals the moral dislocation between creature and Creator. It tests dependence, humility, and trust.

Whereas the secular model treats scarcity as the foundational economic reality, Scripture treats it as a temporary and revelatory pressure. The solution is not technical manipulation or aggressive accumulation, but restored relational alignment—a return to the God who provides manna, multiplies loaves, and withholds rain when justice fails.

In summary, the assumptions that undergird secular economics—autonomy, permanent scarcity, and material progress—are all the result of ontological misalignment. They cannot be corrected by better policy or more precise markets. They require a relational and theological recalibration: an ontology in which value is received, duty is relational, and action is moral.

This foundational realignment prepares the ground for evaluating historical and contemporary economic systems—not merely by their efficacy or justice, but by their underlying vision of the human and of God.

Every economic school of thought carries within it a moral vision, whether declared or denied. Each proposes not only how goods and services should be distributed, but what human beings are, how they ought to live, and what counts as a good life. These models may differ in policy and scope, but they all exhibit a hidden anthropology and latent ontology—often veiled behind charts, data, or ideological claims to neutrality.

This section applies the Deep Parsing Axiom to ten influential economic systems. For each, we identify not only their mechanisms and historical roots, but the moral structure they assume, the degree of ontological misalignment they exhibit, and any points of convergence with a biblical framework. A summarizing table will follow the extended analysis.

Founders: Adam Smith, David Ricardo, John Stuart Mill

Core Ideas: Rational self-interest; the “invisible hand”; minimal government intervention

Classical economics emerged in the Enlightenment period and retains a strong deistic flavor. It assumes a universe in which human beings, though self-interested, are capable of producing social good through decentralized action. The “invisible hand” is a proxy for providence—an impersonal mechanism through which order arises from individual choice.

Smith’s The Theory of Moral Sentiments acknowledges the role of virtue and empathy, but these are ultimately decoupled from divine command or eschatological accountability. The system functions morally only to the extent that individuals remain moderately virtuous.

Ontological commentary: The system promotes decentralization and dignity of choice, but operates without a transcendent source of value or obligation. Value is not defined by God, and moral sentiment is reduced to a soft consensus. Thus, stewardship is replaced by market-validated autonomy.

Founders: Jevons, Menger, Walras

Core Ideas: Marginal utility, mathematical modeling, equilibrium theory

This school formalized economics as a science of preferences and incentives, reducing human beings to utility-maximizing agents. Preferences are considered valid simply because they exist. “Rationality” becomes a technical term: consistent preference expression, regardless of content.

Ontological commentary: Neoclassical economics represents a further abstraction from moral ontology. It treats scarcity as permanent and preference as authoritative, regardless of whether those preferences are virtuous or destructive. The human becomes a calculating unit in a closed system. The imago Dei disappears into algorithmic behaviour.

Founder: John Maynard Keynes

Core Ideas: Government intervention in demand cycles; deficit spending for growth; full employment as priority

Keynesianism arose in response to depression and economic stagnation. It assumes that markets are not self-correcting and that the state must act as an economic agent to ensure stability and employment. Investment is socialized to offset individual volatility.

Ontological commentary: The state becomes a surrogate moral actor, replacing voluntary responsibility with enforced redistribution. Though not explicitly atheistic, Keynes was open about his secular humanism. Compassion is bureaucratized. The state simulates paternal care, but lacks the relational dimension of biblical stewardship. This creates the illusion of justice without relational accountability or covenantal duty.

Founders: Ludwig von Mises, Friedrich Hayek

Core Ideas: Praxeology (the logic of action), anti-coercion, subjective value, decentralized decision-making

Austrian economics affirms that human beings act purposefully and that free exchange respects dignity and avoids coercion. Its emphasis on voluntary interaction and property rights resonates with biblical themes of agency and consent.

Ontological commentary: Austrians defend liberty as a procedural good, but they lack a teleological anchor. Liberty is defended as an end in itself, not as the condition for covenantal stewardship. The system avoids statist coercion but also resists the idea of divinely defined moral constraints on choice. Nonetheless, its respect for agency and decentralized order offers partial consonance with biblical economics, particularly in resisting technocratic overreach.

Figurehead: Milton Friedman

Core Ideas: Monetarism, empirical market testing, economic freedom

The Chicago School shares much with Austrian economics but adds empirical rigor and data-driven validation. Friedman emphasized liberty and warned against government expansion, promoting minimal taxation and private choice.

Ontological commentary: While rhetorically strong on liberty, this system tends to reduce ethics to outcomes. If a policy increases utility or reduces inflation, it is considered good. Efficiency becomes a proxy for virtue. This utilitarian streak lacks any ontological grounding for value or purpose. The moral vision is procedural and pragmatic rather than covenantal.

Founders: Thorstein Veblen, John Commons

Core Ideas: Economic behavior shaped by social norms, habits, and institutions

This school argues that markets do not float above culture; they are embedded in institutions and social expectations. Norms, laws, and narratives shape economic outcomes, often subconsciously.

Ontological commentary: Institutionalism reintroduces semiotic realism—the idea that symbols, norms, and meaning structures govern material life. However, it stops short of affirming divine teleology. Institutions are historically contingent rather than morally anchored. Truth becomes sociological, not transcendent. Thus, the semiotic turn is helpful but lacks a divine plumbline.

Figures: Daniel Kahneman, Richard Thaler

Core Ideas: Humans are predictably irrational; cognitive biases distort choice; “nudge” strategies improve outcomes

Behavioral economics diagnoses many real-world failures of the rational-agent model. It shows that people often act against their own interest due to fear, framing, or habit. Policy-makers can use this knowledge to shape choices more effectively.

Ontological commentary: Behavioral economics recognizes fallenness but cannot name it. It sees distortion but has no doctrine of sin. Solutions are procedural: “nudge” people in better directions. But better by what standard? The system lacks a prescriptive telos. It is pastoral without a shepherd—shaping behavior without asking whether the target of that behavior is good.

Figures: Herman Daly, Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen

Core Ideas: Economy embedded in ecology; sustainability is the central constraint

Ecological economics rightly rejects the idea that growth is infinite. It emphasizes environmental boundaries, long-term sustainability, and systemic integrity. It asks us to live within limits and consider the rights of future generations. Ontological commentary: While this system recovers a stewardship impulse, it often does so without the Creator. Nature is sacred, but not necessarily created. Humans are often framed as parasites rather than image-bearers. In extreme cases, ecological economics slips into pantheism or technocratic authoritarianism—where sustainability becomes a moral end that overrides individual dignity and volition. The form of stewardship is present, but the referent is missing.

Core Ideas: Prohibition of riba (interest), zakat (obligatory giving), emphasis on moral law and distributive justice

Islamic economics frames human action within divine law (Sharia). Economic justice is pursued through a legalistic-moral system with clear boundaries around wealth accumulation, interest, and neglect of the poor.

Ontological commentary: Islamic economics affirms divine ownership and moral constraint, which gives it a stronger metaphysical foundation than secular models. However, it tends to emphasize external conformity over internal transformation. Stewardship is enforced rather than relationally awakened. The moral system is covenantal in structure, but lacks the regenerative power of grace-based transformation as revealed in Christ.

Sources: Torah, Prophets, Gospels, Apostolic Teaching

Core Ideas: Jubilee, stewardship, generosity, accountability, divine ownership

Biblical economics begins not with scarcity, but with abundance entrusted. God owns all things. Man is a steward. The purpose of wealth is not consumption or accumulation, but exempliation—faithful embodiment of God's order through relational responsibility.

Jubilee ensures that wealth does not entrench injustice.

Tithing reaffirms divine ownership and trust.

Almsgiving reflects personal moral accountability.

Parables of Jesus reveal economic behavior as spiritual exposure.

Ontological commentary: This is the only system grounded in axiological objectivity (value defined by God), relational deontology (duty based on divine image and covenant), and modal accountability (praxis as judgment). It neither sacralizes the state nor idolizes the market. It centers the moral agent in relationship to the Creator and neighbor—and treats every resource as a site of either faithfulness or rebellion.

Tithing is often treated as a financial or liturgical detail—a peripheral aspect of religious practice. But when viewed ontologically, tithing becomes a central act of moral and metaphysical realignment. It functions not merely as a rule or offering, but as a material confession of divine ownership, exposing the posture of the steward toward the One who provides. In the biblical economy, the tithe is not optional philanthropy; it is the firstfruits of trust, submission, and recognition that the earth is the Lord’s (Psalm 24:1).

At its core, the tithe declares a fundamental truth: the One True God owns everything. Human beings are not owners, but stewards. When the Israelite brought the first tenth of his harvest, he was not donating from his excess—he was acknowledging divine priority over all increase. The act of tithing placed God at the head of the economic order, not only ritually but ontologically.

“Honor the Lord with your wealth, with the firstfruits of all your crops…” (Proverbs 3:9)

This is not symbolic in the modern sense. It is typophoric—a referential gesture toward an ontological reality. The act of giving the first portion of one’s increase is not merely a sign but a participation in a deeper truth: everything comes from God, and everything returns to Him in faithfulness.

The tithe functions, then, as a covenantal reinstatement. It realigns the steward’s heart with the truth of creation and dependence. It breaks the illusion of autonomy and disrupts the false narrative that wealth is self-generated. To withhold the tithe is not merely stingy—it is an ontological denial of divine ownership.

Critics sometimes argue that tithing is obsolete because it is not reaffirmed as law in the New Testament. But this reveals a misunderstanding of biblical continuity. The proper hermeneutic is this:

Any principle rooted in creation, covenant, or ontological order remains binding unless it is explicitly revoked or fulfilled in Christ.

Tithing, like the Saturday-Sabbath and stewardship, is not first a legal provision—it is a creation-order acknowledgment of divine primacy. Abraham tithed to Melchizedek long before Sinai (Genesis 14:20), and Jacob vowed a tithe to God in Genesis 28. These acts precede law and suggest a pre-Mosaic recognition of God’s claim.

Jesus’ reference to tithing in Matthew 23:23 affirms the practice: “You should have practiced the latter [justice, mercy, faithfulness], without neglecting the former [the tithe].” His concern is not with the tithe per se but with its moral emptiness when unaccompanied by weightier matters.

Thus, the absence of re-legislation in the epistles does not imply abolition. Rather, it reflects a covenantal intensification: New Testament giving is marked by joyful generosity and radical surrender—not less than a tithe, but more. The early believers gave houses, fields, and entire inheritances (Acts 4:32–37). But that which is offered freely must still be grounded in relational accountability—and the tithe remains the foundational gesture of alignment.

In biblical logic, the tithe comes before distributive decision-making. Before allocating to the poor, investing, or consuming, the steward reaffirms who the Owner is. This is essential, for without ontological grounding, generosity can become paternalism, or even idolatry—elevating the recipient or the giver rather than submitting to the Giver of all.

This priority reflects the hierarchical structure of economic faithfulness:

Acknowledge divine ownership (tithe);

Engage in relational generosity (alms, support);

Exercise wise management (investment, growth, inheritance).

Tithing therefore functions not only as obedience, but as cognitive and moral recalibration. It frames every economic decision that follows.

Scripture consistently links God’s provision to the posture of obedience. The promise in Malachi 3:10 is paradigmatic:

“Bring the full tithe into the storehouse… and see if I will not open the windows of heaven…”

This is not a vending-machine prosperity gospel. It is a relational offer of faith-confirming provision. The blessing attached to tithing is not measured solely in surplus—it includes peace, sufficiency, protection, and a recalibrated vision of contentment. The tithe invites the steward into a posture of restful dependency, where God is trusted to multiply what remains.

Those who tithe often testify that the remaining 90% carries further than the full 100%. This is not mystical but ontologically coherent: when one aligns with God’s design, material sufficiency is often a byproduct of moral alignment. The miracle of provision is not always abundance, but adequacy anchored in trust.

The parables of the talents (Matthew 25) and the pounds/minas (Luke 19) are often misread as market parables or productivity fables. But their true focus is moral accountability in delegated stewardship.

Each servant is entrusted with resources—not to consume or hide, but to act. The ones who multiply are not praised for their return, but for their faithful initiative. The one who withholds acts from fear and suspicion—betraying his moral disalignment from the master’s character.

“Well done, good and faithful servant... You have been faithful with a few things; I will put you in charge of many things.” (Matthew 25:21)

This parable reveals the teleological function of economics: it is not an end in itself, but a test field. Earthly economics becomes the proving ground for eternal stewardship. The true reward is not wealth—but increased participation in divine governance: “You shall rule over ten cities.”

Thus, the tithe is the starting point of this stewardship journey—not the end. It opens the door to faithful responsibility, where every decision—however small—becomes an act of moral revelation.

One of the most distinctive features of biblical economics is its insistence on personal moral accountability. Where modern systems often delegate economic compassion to institutions, states, or statistical policies, the Kingdom economy insists that the individual soul is the primary economic agent—not in terms of productivity alone, but in terms of relational responsibility. Economics is not a mechanism for efficiency alone; it is a medium for faithfulness, and faithfulness cannot be automated.

In contemporary discourse, care for the poor is typically framed as a systemic issue to be addressed through public policy, taxation, welfare programs, or institutional charity. While such mechanisms may play supportive roles, the biblical model treats such delegation as incomplete unless it flows from a rightly ordered personal heart. There is no biblical precedent for outsourcing one’s duty of compassion to a governing body and thereby absolving oneself of direct responsibility.

Institutional aid is not invalid, but it is never the primary mode of faithfulness. The moral economy of the Kingdom begins with persons—not programs.

This is not to argue for libertarian individualism, nor to reject collective structures, but to reaffirm the principle that personal economic morality cannot be collectivized. Institutions may amplify mercy, but they cannot replace the soul's encounter with the neighbor in need.

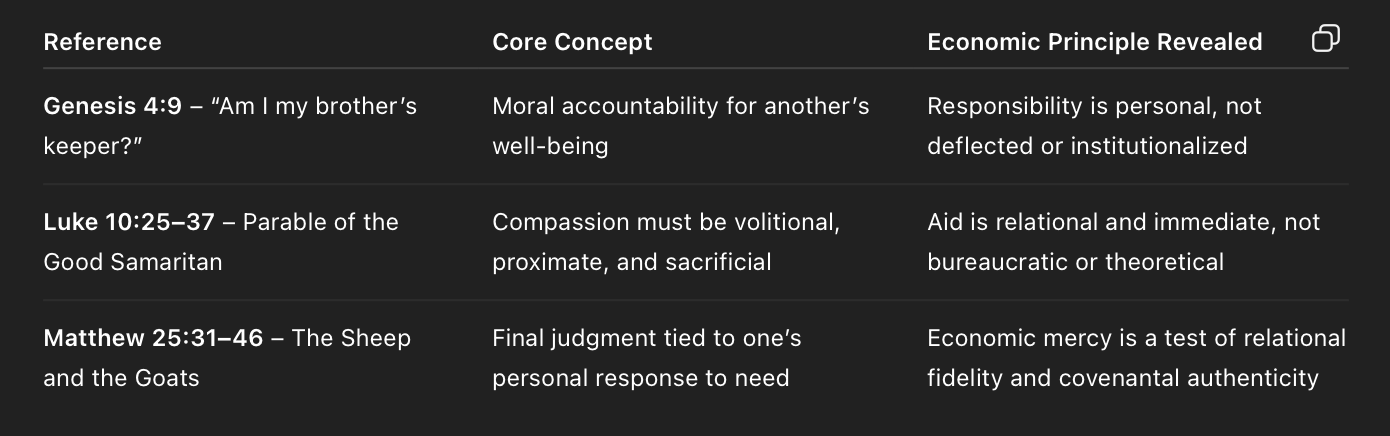

This principle emerges most powerfully through a triangulation of three Scriptural texts, which—when placed side by side—form a coherent theology of personal economic duty:

These three texts represent progressive intensification:

These three texts represent progressive intensification:

Genesis 4 sets the foundational moral principle: one is indeed his brother’s keeper. The denial of that truth (by Cain) results in exile and divine confrontation.

Luke 10 shows what being a “keeper” looks like in action. The Samaritan interrupts his journey, uses personal funds, and takes on risk—demonstrating that true neighbourliness is not theoretical, but enacted.

Matthew 25 elevates the principle to eschatological seriousness: judgment is rendered on the basis of personal, practical mercy. The standard is not doctrinal alignment, but economic fidelity toward the least.

These are not “social gospel” texts. They are ontological disclosures. They reveal what is eternally true: that relational faithfulness is inseparable from economic responsibility.

Within the biblical framework, caring for the needy is not simply commendable—it is ontologically necessary. It is a manifestation of alignment with divine order. The image of God in man demands recognition of the image of God in others. Economic mercy is a moral test, not a social preference.

Hence the striking absence of economic indifference in Jesus’ teachings. Nowhere does He affirm that one may simply “support good policies” or “vote for the right programs” while remaining materially disengaged. The relational economy of the Kingdom demands participation, not proxy.

Moreover, biblical charity is not premised on entitlement or merit. The Samaritan aids a stranger. The sheep minister to “the least of these.” These acts are not merely benevolent—they are typophoric gestures, enacting fidelity to the image-bearing worth of the other and gesturing toward the steward’s alignment with the Father.

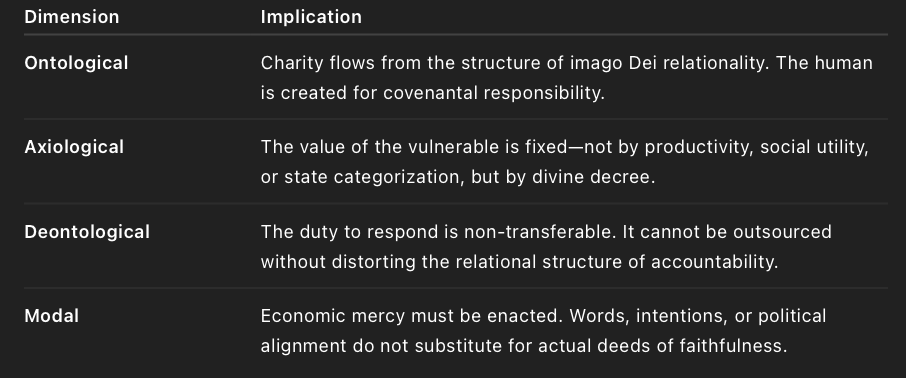

To clarify the theological weight of this principle, we summarize its implications across four ontological dimensions:

This paradigm corrects two common distortions:

Against collectivism, it insists that systems cannot replace personal moral action.

Against atomized individualism, it insists that responsibility flows toward the neighbor, the brother, the stranger—not only the self.

The early church did not treat generosity as peripheral—it was central. Acts 2–5 depicts believers selling property, sharing resources, and treating nothing as their own. This was not early communism, nor mandated redistribution. It was relationally triggered faithfulness in response to the presence of the Spirit and the demands of love.

True charity is not merely almsgiving—it is exempliation. It makes visible the moral fidelity of the steward to the Giver.

In this light, charity is not a good deed, but a moral performance—an enactment of trust, humility, and ontological awareness. To give is to declare: “I am not my own. What I have is not mine. And this person before me is a bearer of worth I am bound to honour.”

If earthly economics is the moral proving ground of stewardship under conditions of scarcity and distortion, then the economy of the Kingdom of God represents the full unveiling of the divine order—an order in which scarcity is abolished, yet moral responsibility remains. The economic life of the believer does not end with the dissolution of sin’s effects. It is transformed, elevated, and brought to fulfillment in a reality where abundance no longer tempts, and poverty no longer hides moral failure.

This section explores the eschatological economy of God’s Kingdom, where eternal stewardship replaces temporary ownership, and where faithfulness—not accumulation—is the eternal metric of honor.

One of the striking features of the biblical vision of the new creation is that material lack is no more:

“They shall build houses and inhabit them; they shall plant vineyards and eat their fruit… They shall not labor in vain.” (Isaiah 65:21–23)

“They shall hunger no more, neither thirst anymore…” (Revelation 7:16)

Yet this removal of scarcity does not eliminate the structure of moral agency. As in Eden, where Adam was called to “work and keep” the garden in the absence of lack (Genesis 2:15), so too in the renewed creation the structure of stewardship remains. Stewardship is not a temporary response to sin but an eternal vocation grounded in creaturehood and proximity to God.

This means that economics is not abolished in the Kingdom—it is redeemed and revealed. The economy of Heaven is not transactional but participatory. It is no longer shadowed by competition or fear but illuminated by joyful accountability. Though scarcity is abolished, this does not mean that liberty or property vanish as categories. Rather, they are ontologically requalified: no longer shielded against theft or injustice, but joyfully exercised within a shared structure of trust. Property remains, but not as exclusion; liberty endures, but not as autonomy. Both are restored as instruments of faithful stewardship. See Appendix E5 for a review of Authority, Rights, and the Kingdom: An Ontological Analysis of Human Government.

Jesus’ parables are not merely didactic stories or moral illustrations. They are ontological mirrors—designed to reveal the hidden structure of the Kingdom by exposing the heart, testing alignment, and forecasting eschatological outcomes. In the realm of economics, these parables unveil the spiritual weight behind resource stewardship and expose the relational metrics by which reward is ultimately measured. They do not describe a transactional economy but a covenantal one, where heart posture, moral fidelity, and response to entrustment determine one’s proximity to the Master.

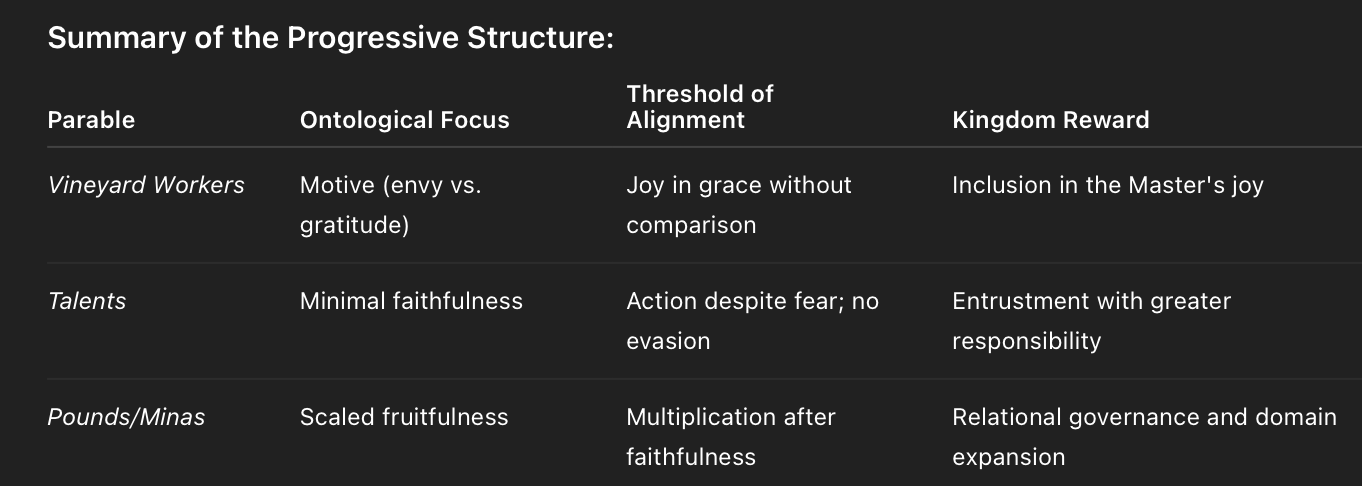

The following three parables form a progressive triad:

Laborers are hired at various times throughout the day, yet all receive the same wage. Those who labored longest object—not because of injustice, but because of comparison. The master replies:

“Friend, I am not being unfair to you… Are you envious because I am generous?”

This is not a parable about labor rights or wage fairness. It is a diagnosis of motive. The Kingdom economy is grace-based, not merit-driven. The metric is not effort but the spirit in which reward is received. The complaint of the early workers reveals that comparison poisons gratitude and resentment disqualifies joy. The parable establishes the first ontological principle of Kingdom stewardship: no amount of labor entitles a soul to envy another's mercy.

Thus, motive—the posture of gratitude vs grievance—is the first filter of reward.

Here, three stewards are entrusted with differing amounts, each “according to his ability.” Two multiply what they are given; one hides his gift and offers back only what was entrusted. His rationale? Fear and suspicion of the master:

“I knew you were a hard man…”

The master condemns this servant—not for failure, but for inaction driven by mistrust. The rebuke is sharp:

“You wicked and lazy servant.”

This parable introduces the universal mandate of stewardship: every person, regardless of capacity, is expected to act. The threshold is not success but movement in faith. Relational alignment demands participation; fear does not excuse evasion. This is not a parable about return on investment—it is about ontological fidelity under delegated trust.

Thus, faithfulness—the willingness to act on entrustment—is the second filter of reward.

Similar to the talents, this parable depicts stewards entrusted with equal resources (a mina each). Upon the master’s return, their yield varies: one has multiplied tenfold, another fivefold. The master responds:

“Well done… You shall rule over ten cities.”

This parable introduces the principle of proportional reward: after motive is purified and minimal faithfulness is demonstrated, the degree of fruitfulness becomes the basis for expanded governance. This is not meritocracy but relational capacity matched to demonstrated trust. The more faithfully a steward aligns with the master’s aims, the more deeply he is invited into shared authority.

Thus, fruitful multiplication—flowing from right motive and active fidelity—is the third and final filter of reward.

Together, these parables present a Kingdom economy where:

Motive must be purified first (gratitude over envy),

Action must be taken faithfully (no paralysis under fear),

Yield then determines relational entrustment (not in merit, but in trust confirmed).

This is not an abstract theology of work—it is the ontological logic of the eschatological economy. Stewardship is not optional. Participation is demanded. But reward is relational, scaled not by input or worth, but by the intersection of faithfulness and grace.

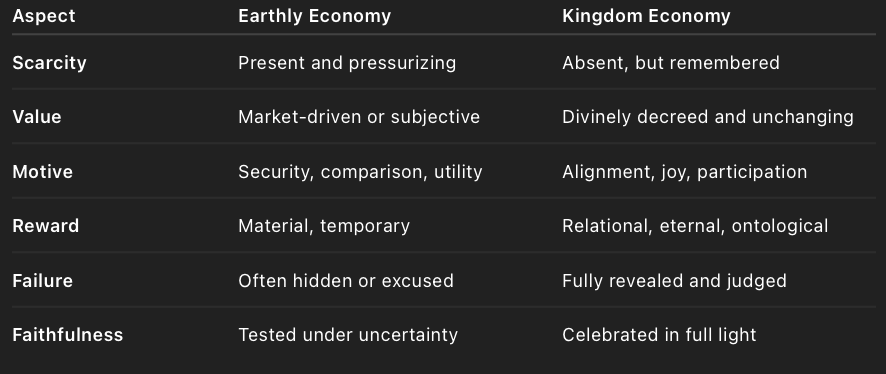

The deepest distinction between earthly and heavenly economics is this: the former is shaped by scarcity and security; the latter is governed by alignment and joy. In the Kingdom:

Accumulation is meaningless. There is no envy, theft, or moth to destroy.

Consumption is unneeded. All satisfaction flows from God.

Exchange is obsolete. Nothing is bought or sold; all is shared in covenant.

Yet none of this abolishes moral responsibility. Rather, it intensifies the visibility of alignment. With temptation removed, the soul’s posture is no longer concealed. Heaven reveals—not erases—what was forged in hidden stewardship on earth.

“If then you have not been faithful in the unrighteous wealth, who will entrust to you the true riches?” (Luke 16:11)

This is the ontological center of the Kingdom’s economy: the use of unrighteous wealth (temporal, perishable, test-based) is the proving ground for entrustment with true riches—those which cannot be corrupted, compared, or lost.

The preceding sections have exposed the deep structural differences between secular and biblical economic systems—not only in mechanism or policy, but in ontological posture. At its core, the divergence is not merely ideological but metaphysical. It concerns the origin of value, the legitimacy of desire, the nature of responsibility, and the very purpose of material goods.

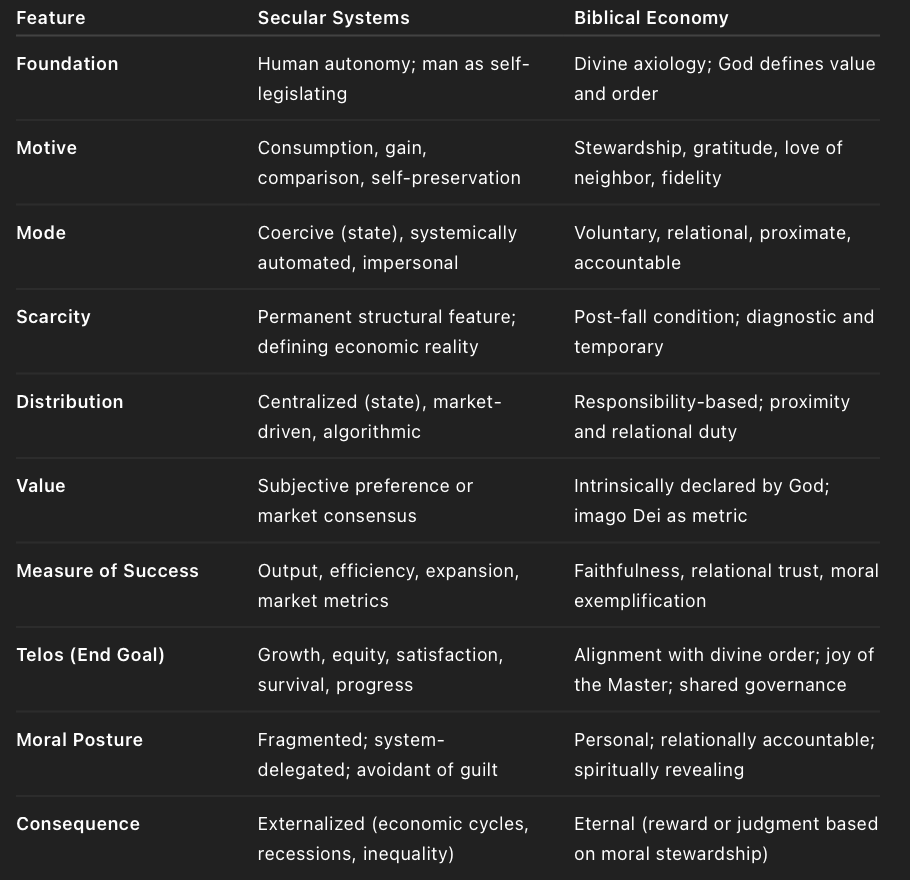

To close, we present a structured contrast between secular economic systems (across the spectrum) and the biblical economy of covenantal stewardship, drawing together the thematic threads of the entire essay.

This table does more than summarize—it uncovers the spiritual DNA of each system. What secular systems treat as technical, the biblical model treats as moral. What others systematize, Scripture personalizes. What others hide in abstraction, God exposes in relationship.

At the center of all biblical economics stands a person, not a policy—a steward accountable to a relational God. Systems may aid or hinder, but they can never absorb this responsibility. All attempts to abstract, defer, automate, or dilute this calling are, ultimately, forms of moral evasion.

This is why Scripture does not spend its energy defining optimal tax rates or growth strategies. It spends its energy confronting hearts. The widow’s mite is worth more than the treasury of the wealthy. The rich fool is condemned not for wealth, but for storing it apart from divine purpose. The Samaritan—not the Levite or the priest—is declared faithful, not because of theory, but because of costly, proximate, enacted mercy.

Economic justice in the Kingdom is not a matter of structure, but of alignment.Not how much was given, but how much was surrendered.Not how much was earned, but how it revealed the soul’s posture.

Economics, then, is not a neutral discipline. It is a moral and metaphysical field in which the true alignment of the soul becomes visible. Every coin given, withheld, spent, or invested becomes a token of alignment or rebellion.

This truth transforms the economy from a site of anxiety into a site of worship. It redefines wealth not as danger or blessing, but as exposure. It recasts poverty not as failure, but as a potential site of divine encounter. And it calls every believer not to activism alone, but to radical accountability under the eyes of the God who gave all.

“You have been faithful with a few things…Enter into the joy of your Master.” (Matthew 25:23)

This is the final verdict of the Kingdom economy. Not efficiency. Not comparison. Not profit.But faithfulness, joy, and presence.