This appendix continues directly from Appendix E6 , which traced the divine architecture of justice: the fourfold pattern of moral accountability (motive, intent, act, outcome) and the sevenfold pattern of divine reckoning (epideictic, elenctic, restorative, and eschatological). Here we examine what occurs when that structure is abandoned. We trace the regression of human justice systems—from relational repair to bureaucratic containment, and finally to symbolic performance divorced from truth. The consequence is not merely administrative failure, but ontological collapse: justice without persons, punishment without repentance, restitution without repair.

Modern legal systems are widely regarded as triumphs of civilisation—systems that have, over centuries, evolved from vengeance to impartiality, from tribalism to universal rights, from emotional retribution to rational procedure. They are celebrated as symbols of moral progress, embedded with checks, balances, and codified protections that earlier societies lacked.

And yet this narrative is deeply misleading.

What is commonly presented as progress is often, in fact, a profound displacement. Justice has not been clarified—it has been abstracted. It has not become more personal—it has become more systemic. And above all, it has lost its ontological anchor: the grounding in reality, personhood, and moral truth that once gave justice its weight. The modern system simulates justice—invoking its language, preserving its ritual—but severed from relational encounter and moral repair, it no longer enacts what it claims to preserve.

The shift is subtle but devastating. Where earlier systems—however rudimentary—still required the offender to answer to the person harmed, modern law frames the crime as an offense against the state. Where earlier redress involved tangible restitution, modern remedies often route through fines and incarceration, neither of which restore what was lost. The victim is repositioned as a witness. The community becomes a bystander. The offender is absorbed into a bureaucratic machine that disciplines without reconciling, punishes without exposing, and moves on without repairing.

This is not simply moral drift. It is ontological inversion: justice redefined not by its purpose—moral redress and relational restoration—but by its function: institutional legitimacy, social order, and procedural containment.

This appendix continues directly from Appendix E6 , which outlined the fourfold human template of justice (motive, intent, act, outcome) and the sevenfold divine architecture of moral reckoning. There we saw how biblical justice moves beyond appearances into exposure, restitution, and reconciliation. Here, we follow the trajectory in reverse: how human systems have lost not only access to divine justice, but even to the relational clarity that once governed human redress.

But this is not merely a historical or theoretical concern. When justice is abstracted from ontology, it no longer protects the vulnerable, confronts the guilty, or reconciles the alienated. It ceases to be just. It becomes a performance—a simulation of justice enacted within a typological void.

Our analysis begins by briefly reestablishing the structure of relational justice in its fourfold biblical and historical form, before tracking its displacement through abstraction, the emergence of simulation, and the systemic collapse that follows. The aim is not nostalgia for imperfect systems, but a clear-eyed reckoning: justice without truth, without personhood, without covenant—is not justice at all.

Before justice was institutionalised, it was interpersonal. Long before legal systems were codified into state machinery, communities—biblical, tribal, civic—understood wrongdoing as a rupture in relationship. Justice was not the cold neutralization of threat, but the moral pursuit of alignment: between persons, truth, and the moral order. And central to this pursuit was the recognition that not all wrongs are equal, nor all intentions alike. Moral responsibility, if it was to be just, had to be structured—not merely in consequence, but in the logic of guilt itself.

This structure, as outlined in Appendix E6 , can be traced in the fourfold moral template that undergirds biblical and early legal models of justice:

Motive – the hidden disposition of the heart, whether rooted in envy, greed, malice, fear, or indifference.

Intent – the formed purpose to act, which reveals whether the deed was planned, reckless, negligent, or accidental.

Act – the concrete event, the physical or verbal execution of the will in time and space.

Outcome – the tangible or intangible consequences borne by the victim or community.

This fourfold sequence is not artificial—it arises naturally in all moral reasoning. It is the logic behind the biblical distinctions between murder and manslaughter, theft and restitution, negligence and malice. For example, in Exodus 22, restitution varies not only by object stolen but by context—whether it was returned, lost, or destroyed. In Leviticus 6, guilt offerings are accompanied by repayment plus a fifth, signalling that sin is not erased by repayment alone but must also be acknowledged before God.

Importantly, these systems did not treat harm as purely transactional. Restitution was relational. The wrongdoer had to return to the one harmed, to face them, and to acknowledge the breach—not just to balance accounts but to reopen the moral ledger that had been violated.

This same structure echoes across early Anglo-Saxon law, where the wergild (“man-price”) required compensation directly to the kin of the harmed or slain. The amount was not arbitrary—it reflected the social and moral weight of the breach. And in many frontier communities, where no overarching government existed, justice was negotiated within the community—sometimes harshly, but almost always with the victim and offender in view of each other.

These systems were undeniably imperfect. They bore the inequities of caste, gender, and social power. But they retained something which the modern system, for all its sophistication, has forfeited: they preserved the relational grammar of justice. The breach was personal. The repair had to be personal. And the confrontation of wrong could not be outsourced to symbols or paperwork.

To be clear: the goal is not to restore primitive law, but to recover the logic embedded in it—the recognition that true justice must be morally structured, relationally grounded, and responsive to the full shape of wrongdoing. When this fourfold architecture is abandoned or obscured, justice loses its ability to see.

It is this moral blindness that we now trace—not merely in contrast with divine justice, but as the necessary prelude to its loss.

If the fourfold structure of justice allows for human moral accountability, the sevenfold pattern revealed in Scripture discloses God’s ontological justice—a justice not merely responsive to harm, but exposing of all that is hidden, all that resists the truth, and all that stands in need of full repair. Where human systems necessarily stop short—limited by evidence, memory, or procedural reach—God’s justice sees all, names all, and restores or condemns with final clarity.

In Appendix E6 , we outlined this sevenfold framework not as an abstraction but as the revealed logic by which God confronts evil. It is worth recalling briefly:

Acknowledgment of Value Lost – What was desecrated—person, truth, relationship—is not forgotten but named.

Consequences Fully Traced – The web of harm, including unseen victims and long-term effects, is drawn into the light.

Intent Exposed – Not only what was done, but what was willed, is revealed; hidden malice does not remain hidden.

Ripple Effects Revealed – The structural and collateral damage—to institutions, communities, generations—is confronted.

Truth Publicly Disclosed – The record is opened; the narrative reclaimed; the moral facts laid bare before the onlooking community.

Relational Reckoning Clarified – The moral and covenantal distance between the offender, the offended, and God is brought to account.

Restitution Multiplied and Completed – Not symbolic compensation but full ontological reversal: either through redemptive grace or retributive judgment.

This sevenfold structure is not reducible to any human model. It is not a judicial process. It is a revelatory act—a divine confrontation in which every layer of reality, hidden or denied, is reconciled to the truth. Its purpose is not merely to assign guilt or dispense consequence, but to restructure moral reality around God's righteousness.

This is what makes divine justice unbearable to those who resist it, and unshakably beautiful to those who long for the truth. It does not simply answer the question “What happened?” but also “Why did it happen?”, “Who was harmed?”, “What was lost?”, and ultimately, “What will be made whole?”

Such justice is not procedural. It is ontological and relational. It restores not only what was taken, but what was hidden. It does not leave falsehood standing. And unlike all human systems, it cannot be deceived.

It is important to grasp this before we continue: God’s justice is not merely greater in magnitude, but fundamentally different in kind. It is personal, universal, and incorruptible. It neither depends on nor is limited by human systems. And while the fourfold model enables communities to pursue partial redress, even at their best, these systems cannot enact sevenfold justice. They can only participate in its shadow—or, more often, simulate its language while excluding its reality.

In the next section, we will trace how this simulation begins—not with malice, but with the loss of relational equity and the gradual substitution of procedure for truth.

The collapse of modern justice did not occur in a vacuum. It was the result of a long, deliberate reconfiguration—an ontological displacement concealed behind the rhetoric of progress. At the heart of this shift lies a largely forgotten but foundational principle: that justice, historically and biblically, was structured not to satisfy the state, but to restore the person harmed. When this was displaced—quietly, and then systematically—what followed was not moral refinement, but relational erasure.

In the biblical model, the locus of restitution is unequivocal. The thief, the defrauder, or the negligent party is required to make redress directly to the one harmed. Exodus 22 outlines a scale of repayment: double for theft, fourfold or fivefold for livestock, restitution with added compensation in cases of loss. Leviticus 6 affirms that even where guilt offerings to God are involved, they must follow full material restoration to the injured party:

“He shall restore what he took violently away… and shall add the fifth part more thereto, and give it unto him to whom it appertaineth.” (Lev. 6:5)

This was not symbolic. It was the ontological logic of moral repair: the one who breached must answer to the one who suffered.

This logic echoed throughout pre-modern jurisprudence. The early Anglo-Saxon codes (e.g., the Laws of Æthelberht and Alfred) contain detailed wergild tables—monetary compensations scaled to the status of the injured, from freemen to nobility. In every case, the assumption was clear: the harm required personal recompense, not abstract punishment. The crime did not simply violate order—it violated someone, and that someone must be repaid.

Similarly, Roman law, particularly under the Lex Aquilia, treated injury and property damage as requiring direct restitution to the victim or their kin. Even the Justinian Digest preserves this structure:

“Where a slave or a quadruped is wrongfully killed, the killer is bound to pay the owner.” — Digest, Book 9

In these traditions, justice was not nationalised. It was not litigated in the name of the empire, but in the name of the wronged.

Even into the Enlightenment era, legal scholars such as William Blackstone affirmed this historical architecture. In his Commentaries on the Laws of England, he distinguishes between public crimes and private wrongs, explicitly stating:

“A civil injury is an infringement or privation of the civil rights which belong to individuals… and are remedied by the particular suffering party.” — Commentaries, Book III, Ch. 1

This model—a relational, restorative model—was not merely ancient. It was normal. It was the assumed grammar of justice across millennia of legal history. Its disappearance from public consciousness is not incidental. It has been deliberately overwritten.

With the rise of monarchic and later statist authority, the structure of justice was slowly redefined. Harm was no longer a breach between persons, but a violation of public order. The crown, and later the state, positioned itself as the primary victim. In doing so, it transformed the logic of redress:

Restitution to the victim was displaced by fines to the state.

Moral accountability was replaced by loyalty to sovereign order.

The offender’s guilt was mediated through a system, not answered to a person.

This shift was gradual, but total. By the time modern legal frameworks had matured, the victim had been fully repositioned—from participant to observer, from recipient of restitution to passive symbol. Offenders were sentenced not in view of the harm they caused, but according to categories of “offense against the people,” “violation of statute,” or “disturbance of order.”

The Chancery courts in England—originally formed to counterbalance this drift—sought to preserve moral discretion. Their motto was explicit:

“Justice according to conscience, not merely code.”

But over time, even these courts were subsumed into the machinery they once restrained. Equity became standardised. Conscience was proceduralised. And the judge who once mediated between persons became a technician of precedent.

Justice, as once understood in biblical and early legal frameworks, began with the assumption that all wrongdoing was first and foremost relational. A wrongdoer stood in breach not only of divine expectations but of covenantal integrity between persons. The act of theft, fraud, slander, or injury was not primarily an infraction against a code, but a rupture of trust, an ontological wound that demanded restitution to the person harmed—and acknowledgment before the God who saw.

The early legal codes reflected this architecture. In ancient Israel, justice required that the wrongdoer restore what was taken:

“He shall restore what he took violently away… and give it unto him to whom it appertaineth” (Leviticus 6:5).The wrong was not against a statute; it was against a person, in the presence of God. Similarly, in Roman law, even under imperial centralisation, the Lex Aquilia bound the wrongdoer to the injured party—compensation flowed to the victim, not the state. And in Anglo-Saxon common law, the system of wergild(“man-price”) assigned calibrated compensation for harm, measured person to person. The entire logic of justice presupposed relational fracture and relational remedy.

But over centuries, through a subtle and often unacknowledged sequence of displacements, this relational architecture was redirected. What began as a moral breach between persons, overseen by God, was reinterpreted—first as a violation against the Church’s spiritual order, then as a violation of the state’s public order. In both cases, the true referents of justice were substituted. The relational victim was displaced. The Creator was bureaucratised. And justice, though still cloaked in moral and theological language, was now performed through institutional proxies.

This did not occur by public decree, but by a semantic drift, a shift in emphasis so gradual it passed unnoticed. The key redirection took place at the level of ontological referent:

The Church claimed authority to mediate divine law.

The State claimed authority to mediate public peace.

And conscience—once awakened by direct encounter with the person harmed—was gradually sedated by procedural closure.

The sleight of hand was enabled by a redefinition of sin itself. In early Augustinian theology, sin came to be framed less as a covenantal rupture or relational defection, and more as a transgression of divine law. This paved the way for the Church to become custodian of that law, dispensing absolution through sacramental mechanisms: confession, penance, excommunication. In this model, the victim became incidental. What mattered was whether the wrongdoer had submitted to ecclesiastical process and been ritually absolved.

When the authority of the Church began to wane, the same logic was transferred to the monarchic state. The crime was no longer against God directly, nor against the injured party, but against “the king’s peace”. The sovereign—whether crown or republic—became the recipient of justice. Trials retained the forms of biblical judgment: witnesses, guilt, verdict, consequence. But the subject had shifted. The victim became a witness, occasionally a petitioner, but no longer the principal. The offender became an object to be disciplined, not reconciled.

This marked a profound ontological reversal. Justice, which had once been a moral reckoning before God and neighbour, was now a symbolic transaction between citizen and institution. The actual relational rupture was no longer addressed. Instead, harm was reclassified as disorder, and the agent of redress became the mechanism of the state.

The relational became procedural.The covenantal became forensic.The personal became systemic.

Yet the vocabulary remained unchanged. “Justice,” “guilt,” “restitution,” “law,” and even “repentance” continued to circulate—but their referents had been re-routed. The Church spoke of the Body of Christ, the Crown of the Realm, the Republic of the People. In each case, the collective absorbed the wound, and the institutions interposed themselves between offender and victim—between man and man, and man and God.

This was not merely a change in jurisdiction. It was a simulated continuity—the retention of sacred vocabulary divorced from sacred function.

It became possible to serve time without making amends. To be exonerated by procedure without encountering the person harmed. To be ritually cleansed through sacrament or sentencing, while the original moral fracture remained unacknowledged.

This is the great juridical reversal: a transference of moral reality from relation to institution, from presenceto process, from conscience to code.And it is this reversal that prepares the way for the full collapse of equity and the emergence of justice as simulation.

Once the ontological referent of justice had been displaced—from neighbour to institution, from God to proxy—the outer structures of equity could remain intact while their inner logic dissolved. Courts still convened. Oaths were still sworn. Verdicts were still pronounced. But the telos of justice had quietly shifted. Where once it sought to restore what had been broken between persons before the sight of God, it now sought to preserve the order of the system, to reinforce institutional legitimacy, and to manage risk.

This is what makes the collapse of equity so difficult to detect: it is camouflaged by continuity. Nothing appears to have been removed. But everything has been reassigned. The forms remain, but they now serve different ends.

Even those institutions once explicitly tasked with moral discernment—the courts of equity—eventually succumbed. The Court of Chancery, founded to temper the rigidity of common law with appeals to conscience, was gradually proceduralised. Over time, equity itself was codified. Discretion became doctrine. Mercy became mechanism. Conscience—once an active principle—became a rhetorical placeholder.

But this was not merely a shift in jurisprudence. It was an ontological collapse. For equity, at its core, is not a legal supplement. It is a moral posture: a willingness to enter into the reality of the other, to weigh not just the act but the heart behind it, and to seek not merely compliance but restoration. When that posture is replaced with algorithmic fairness, with distributive calculus, or with impartial process, the name may remain—but the substance is gone.

A just system without justice is not a paradox. It is a simulation.

Victims are told they have been “heard,” though nothing has been restored. Offenders are “held accountable,” though no one has been reconciled. Courts are declared fair, though the wounded remain invisible and the penitent untransformed. In such systems, equity is not abolished; it is performed—a moral gesture hollowed out by institutional abstraction.

At its worst, this becomes self-justifying: the more procedure is perfected, the more conscience is suppressed. The more neutral the mechanism, the more absolute its claim to moral authority. And so the collapse proceeds under the guise of progress.

But beneath this procedural smoothness lies a silence—the silence of moral fracture unacknowledged, of victims displaced, of guilt unreckoned with.

For equity to exist, it must see the person.For justice to be real, it must name the breach.For restoration to occur, the moral structure must remain intact.

We no longer live within that structure. We live in its architectural shadow. The names have not changed—but their meanings have been severed from their roots.

This is the collapse of equity: not merely a breakdown in fairness, but the loss of ontological vision. Justice has become a choreography—ritualised, abstracted, and remote—where neither God, nor neighbour, nor moral consequence is any longer visible in the courtroom. The light of restoration has been replaced with the glow of legitimacy. The voice of conscience with the verdict of compliance.

And in this collapse, justice becomes the prelude to simulation—a performance whose success is measured not by restoration, but by how convincingly it can imitate what once was real.

Once the relational core of justice is severed—once the victim is proceduralised, the wrongdoer is abstracted, and the presence of God is displaced—the system does not acknowledge this loss. It compensates. It must still command legitimacy. It must still appear to function. And so it simulates. The language of justice is preserved. The gestures remain. But their referents have vanished.

This creates what we have elsewhere termed the typophoric void. In biblical and moral usage, typophora describes a gesture or utterance that points toward a real, ontologically grounded category. True justice is typophoric because it refers to—and participates in—a relational moral reality: it acknowledges the breach, names the wrongdoer, honours the image of God in the victim, and calls all parties into moral exposure under divine order.

But once that moral ontology is displaced—once justice no longer seeks restitution between persons, nor restoration before God—the gestures remain, but their reference collapses. The courtroom declares that “justice has been served,” but there is no relational repair. No restitution. No reconciliation. The act becomes a voided sign—a typophoric shell gesturing toward a vanished reality.

This is not mere error. It is effigiation: the projection of moral form without moral substance.Like a statue of justice held aloft in a society that no longer believes in truth, the system preserves the image to secure public trust, while deliberately excluding the reality that once gave it meaning.

In such a system, justice is not distorted. It is replaced. Not broken, but substituted. The structure is intact. The rites are observed. But the soul is gone. The courtroom becomes a stage where moral gestures are reenacted for the sake of legitimacy. Yet behind the gavel, the robes, and the solemn language, no one is being restored. No one is being made whole. And no one is answering to the God who sees.

This is not merely legal evolution. It is ontological simulation—the reenactment of justice as a public performance whose meaning has been internally reassigned.

The simulation of justice is most easily seen not in its philosophical articulation, but in its institutional application—where harm remains unrepaired, conscience is unengaged, and closure is pronounced without exposure. What follows are two cases—one systemic, one personal—that illustrate how typophoric gestures are retained even as relational repair is excluded.

A multinational corporation knowingly releases toxic waste into a rural water system. Crops fail. Illness spreads. Families are displaced. Years later, after media pressure and legal investigation, the company is fined a substantial amount by a regulatory agency. The funds are absorbed into the national treasury. No direct restitution is offered. No apology is issued. No moral hearing occurs between offender and victim.

And yet, the press releases declare: “Justice has been served.”

But nothing has been restored. The people harmed remain unseen. The funds do not reach them. The act is treated not as a relational breach, but as a violation of regulatory order. The fine is not a reckoning; it is a transaction. The victims are not reconciled; they are procedural background. The ritual of penalty is observed—but the ontological structure of justice is gone.

This is effigiation: the projection of moral legitimacy in place of moral reality. The phrase “justice has been served” functions as a typophoric simulation, gesturing toward an order it no longer enacts.

A man’s identity is stolen and used to commit widespread financial fraud. His credit is destroyed. His job prospects collapse. His family suffers. Eventually, the offender is caught, tried, and sentenced. But at no point in the legal process is the victim named. No restitution is ordered. No apology is given. No confrontation occurs. The courtroom never hears his voice.

The system declares closure. The wrong is “accounted for.” The offender is punished. But the breach remains unrepaired. The man is still alienated from the life he once lived. The court acted upon the crime, but not upon the injury. It satisfied itself, but not the wronged.

This is not simply negligence. It is the substitution of process for person. The victim was not forgotten—he was rendered irrelevant to the simulation. What mattered was that the machine ran, not that the man healed.

These simulations are not anomalies. They are the design logic of a system that has decoupled its moral language from its moral referents. A legal order that no longer seeks relational repair must offer symbolic closure in its place. It must speak justice even when it no longer performs it. And so it performs.

The courtroom becomes a stage—not in the cynical sense of mere theatre, but in the more haunting sense of liturgical mimicry: a rite observed in absence of the Presence it once served. The robes are worn. The verdict is read. The language of justice is intoned. But there is no confrontation of the soul. No restitution to the injured. No exposure before God.

The system must keep the forms because it has lost the truth.It must retain the gestures, because it cannot afford to reattach them to their original demands.

In this frame, justice becomes a grammar detached from meaning. Words like “due process,” “equity,” “accountability,” and “reform” are still spoken—but they function within a closed semantic system. They no longer point outward to covenant, conscience, or divine order. They point inward—to the self-preservation of the institution.

This is not merely procedural drift. It is an ontological mutation. The very possibility of justice as moral restoration has been replaced by the satisfaction of institutional requirements. The court no longer sees persons. It sees evidence, precedent, admissibility, exposure risk. And so, without seeing, it renders judgment. Without hearing, it pronounces closure.

And yet, the conscience of the public must still be managed. The simulation persists because it is institutionally necessary. Without it, the system would collapse under its own contradiction. It must be believed to be just—even when it no longer heals the breach it claims to remedy.

Thus, modern justice becomes ritual without reckoning. The typophoric shell is preserved. The language is curated. But the referent—the divine gaze, the moral wound, the neighbour harmed—is nowhere present. The system performs justice without relation, without presence, without truth.

This is not justice corrupted. It is justice transfigured into effigiation. Not the failure of equity, but the hollowing of its core. Not the absence of structure, but the absence of God.

What remains is not justice—but the choreography of its simulation. Modern jurisprudence no longer asks who was harmed, what was violated, or what must be restored. It asks only what can be proved, who has standing, and whether a procedure has been satisfied. In this silence, the very premise of justice is lost. The law no longer points beyond itself. It no longer trembles before a transcendent Judge. It speaks of burdens of proof and admissible evidence while refusing to name the burdened or the wounded. It secures verdicts while the truth is left bleeding by the roadside. What began as covenantal repair has become forensic containment. And in doing so, the legal system reveals its final betrayal: not that it fails to deliver justice, but that it no longer even believes justice is real. It believes only in itself—while still claiming, in abstraction, to serve the 'greater good.

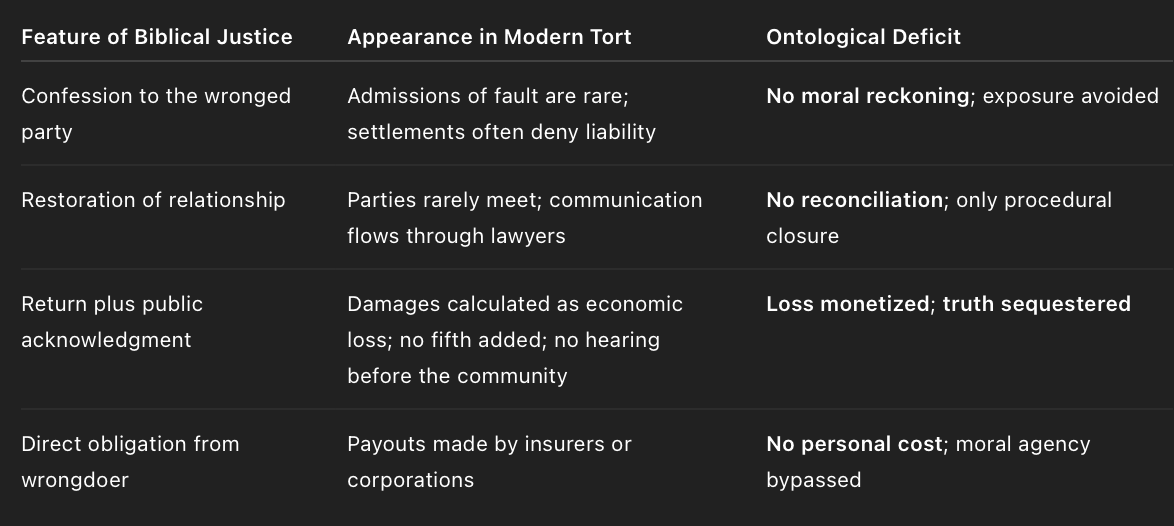

At first glance, tort law appears to preserve what most of the legal system has lost: a direct grievance brought by the injured party against the one who caused the harm. There is no abstraction into crimes against the state, no prosecutor standing in place of the victim. The wronged person initiates the complaint. The accused is named. A judge or jury renders a verdict. Compensation is ordered. Of all the remnants of ancient justice still visible today, this is the one most likely to be cited in defense of the system’s legitimacy. But beneath the surface, even tort law has undergone an ontological deflation.

Tort law does not restore covenant. It converts injury into liability, then liability into dollars. Its function is not relational repair but economic closure. The language of restitution may be borrowed, but its referents are systematically redefined.

Even when tort achieves partial justice—through financial compensation, deterrent judgment, or precedent-setting remedy—it does so behind a veil. The human confrontation is managed. The legal process substitutes representation for presence, transaction for repentance, settlement for restoration. Confidentiality agreements and gag orders often prevent the victim from ever speaking freely about what happened. Restitution is achieved, if at all, in silence.

This is not to say that tort is worthless. In many cases, it is the only tool available to prevent impunity. It can recover real costs, check corporate negligence, and offer victims a symbolic acknowledgment. But symbol is not substance. A cheque, however large, cannot substitute for relational repair. A verdict, however just, cannot confront the soul.

Thus, even in the best-case scenario—where a plaintiff prevails and is paid—the system delivers a facsimile of justice without the encounter that justice requires. Civil court, once the last frontier of victim-driven remedy, now functions within the same simulation architecture: controlled exposure, procedural substitute, institutional closure. It preserves the form. But not the fellowship. Not the wound. Not the truth.

What remains is not justice—but the choreography of its simulation. Modern jurisprudence no longer asks who was harmed, what was violated, or what must be restored. It asks only what can be proved, who has standing, and whether a procedure has been satisfied. In this silence, the very premise of justice is lost. The law no longer points beyond itself. It no longer trembles before a transcendent Judge. It speaks of burdens of proof and admissible evidence while refusing to name the burdened or the wounded. It secures verdicts while the truth is left bleeding by the roadside. What began as covenantal repair has become forensic containment. And in doing so, the legal system reveals its final betrayal: not that it fails to deliver justice, but that it no longer even believes justice is real. It believes only in itself.

The failure of modern justice is not merely the result of poor implementation, political bias, or bureaucratic bloat—though all of these exist. Its failure is systemic, because it is ontological: it no longer rests on a truthful account of what a human is, what a wrong is, and what repair demands. It has ceased to deal in real things, and now traffics primarily in abstractions.

This deeper structural breakdown can be understood through the framework of the Tetradic Constrain of Ontology (TCO) , previously developed to expose all evasions of moral and metaphysical truth. Every evasion—whether in law, ethics, or philosophy—can be traced to the suppression or distortion of one or more of four ontological pillars: Reality, Perception, Reason, and Personality. In justice systems, these distortions map with particular clarity.

Justice must begin with recognising what happened—the actual harm done, to real persons, in real situations. But modern systems frequently retranslate reality into legally acceptable categories, reducing nuanced moral wrongs into administrative boxes.

If a woman is psychologically terrorised in a non-physical way, but no specific statute recognises it, there may be no legal case—even though the moral reality is obvious to all who observe it. Conversely, a minor procedural violation (e.g., a regulatory technicality) may receive disproportionate attention, simply because it fits the system’s grid.

What is ontologically real is not necessarily what is legally legible. The truth of the event is displaced by the structure of what can be processed.

Once reality is displaced, perception becomes institutionalised. That is, the system is built to perceive only what it is structured to detect. It cannot “see” moral injury that is spiritual, relational, or covenantal. It can quantify damages but cannot discern defilement. It can assign penalties but cannot recognise betrayal.

Victims whose experiences fall outside the grid often feel this acutely. Their trauma is minimised not because no one believes them, but because no one is authorised to see it. The perception of justice becomes filtered through a frame that hides moral meaning while claiming neutrality.

In earlier models of justice, especially biblical and classical ones, reason was tethered to conscience. Proportionality, equity, and relational responsibility were discerned by moral wisdom, not merely by precedent or sentencing guidelines.

Modern systems, by contrast, replace wisdom with calibration. Sentences are computed, not reasoned. Restitution is capped or standardised. The logic that once sought reconciliation now protects consistency. And consistency, severed from ontological reality, becomes a substitute for truth.

The system reasons inwardly—for procedural coherence—not outwardly, for moral alignment.

Perhaps the most tragic collapse is here. Justice is, at its core, a moral encounter between persons—a recognition that one image-bearer has violated another, and that something must be done to make it right. When this is replaced with impersonal process, justice loses its heart.

In modern systems:

The offender becomes a case file, not a soul.

The victim becomes a party, not a person.

The courtroom becomes a theatre, not a place of confrontation.

Face-to-face encounters—where repentance might be awakened or truth might be spoken—are systemically discouraged. Moral exposure is replaced by representation. And the language of “closure” replaces the reality of reconciliation.

These four breakdowns are not isolated. They are interlocked—a failure of perception leads to a distortion of reason, which enables the displacement of reality, and culminates in the erasure of personality.

This is why the failure of justice is not episodic. It is not merely the result of bad actors or corrupt judges. It is structural. The system is built to fail, because it has been designed around evasion of moral truth. And wherever justice is no longer anchored in ontology—no longer beholden to what is real—it becomes performative by necessity.

In the next section, we will examine the cascading consequences of this ontological collapse: the erasure of moral debt, the concealment of moral agency, and the insulation of the system from moral feedback. In short, what happens when the ledger is lost.

These four breakdowns are not isolated. They are interlocked—a failure of perception leads to a distortion of reason, which enables the displacement of reality, and culminates in the erasure of personality.

This is why the failure of justice is not episodic. It is not merely the result of bad actors or corrupt judges. It is structural. The system is built to fail, because it has been designed around evasion of moral truth. And wherever justice is no longer anchored in ontology—no longer beholden to what is real—it becomes performative by necessity.

In the next section, we will examine the cascading consequences of this ontological collapse: the erasure of moral debt, the concealment of moral agency, and the insulation of the system from moral feedback. In short, what happens when the ledger is lost.

The ledger is one of the most ancient images of justice: a moral record in which wrongs are remembered, debts are tallied, and repair is sought. In biblical thought, God keeps such a ledger—not as a punitive tally sheet, but as a reflection of moral reality. Every harm, every act of repentance, every cry of the oppressed is inscribed. This is not metaphor. It is the theological claim that nothing morally real is lost or hidden.

But in a system that has displaced reality, obscured perception, fragmented reason, and anonymised personhood, the ledger is no longer kept. It is replaced with procedural equivalents: case numbers, sentencing reports, financial settlements. These may resemble moral records, but they are quantifications of process, not registers of truth. The system does not forget—because it never truly knew.

The result is a threefold disappearance: of the victim, the offender, and the moral community. Each is severed from the relational structure that justice demands. Each is left in a different kind of exile.

In modern justice, the victim often becomes a spectator to their own case. They may be called to testify, but they are not the primary concern. Their healing is not the goal. Their restitution is rarely direct. In criminal law, they may receive no material repair at all. Even in civil proceedings, the compensation may be delayed, negotiated down, or symbolic.

Worse still, the moral weight of their harm is filtered through systems designed to neutralise emotion, suppress narrative, and avoid confrontation. A woman whose dignity is violated, a family whose reputation is destroyed, a community whose trust is shattered—all may have their stories reduced to filings and rulings.

The ledger of their harm is not denied, but it is misfiled. It exists somewhere in the system’s archive, but not in its conscience.

Victims often walk away feeling unseen. Not because the system failed to document their loss, but because no one looked at it with moral eyes.

The modern offender is not invited into confrontation with the one they harmed. They are advised, managed, and processed. A plea deal is struck. A sentence is assigned. They are coached on how to avoid incriminating themselves, but rarely challenged to acknowledge their guilt. At no point is the victim’s face placed before them, nor the reality of the harm pressed into their conscience.

In older systems—especially biblical ones—this was not possible. A thief repaid double to the person harmed. A murderer fled to a city of refuge in view of the family he had wronged. Even pagan codes required reckoning between persons, not simply between subject and sovereign.

But modern systems create distance—buffering the offender from the weight of exposure. They are punished without being confronted. And in many cases, they are punished without even being revealed—their true motives, their spiritual posture, their moral blindness remain intact, unchallenged.

Without elenxis—without the unveiling of guilt—there can be no repentance. And without repentance, punishment becomes hollow: a consequence without a reckoning.

In the absence of relational repair, the system must preserve its own authority. It cannot admit failure without risking collapse. So it builds in self-reinforcing mechanisms: appeals processes, review boards, official statements, media protocols. All designed not primarily to correct, but to contain. It cannot grieve. It cannot repent. It cannot be shamed.

This is the ultimate irony: the institution designed to confront wrong becomes the institution least able to face its own.

No one within the system is accountable for the system. No one stands in the place of the community, speaking on behalf of victims long ignored, or judgments wrongly made. The community is invited to trust the process, but never to challenge the process from within a higher moral order.

And so, the ledger—once the sacred record of moral account—is replaced by a managed archive. The reality of harm is stored, redacted, and processed—but never truly answered.

In the next section, we will turn toward the possibility of recovery—not through institutional reform, but through a return to moral ontology: where justice begins again with persons, truth, and God. Where the ledger is reopened, and the repair of what was lost becomes thinkable once more.

If the modern justice system is characterised by abstraction, simulation, and ontological displacement, then recovery is not simply a matter of reforming procedures or increasing efficiency. It requires something far deeper: a return to truth, personhood, and covenantal moral reality. It requires justice to be re-grounded—not in sentiment, not in precedent, not in power—but in God.

Biblical justice offers this recovery—not merely as a theological ideal, but as a revealed structure in which persons are known, wrongs are confronted, and relationships are repaired. It is a justice that speaks to what was broken, not just what was unlawful. And it makes possible what modern systems no longer attempt: restitution that is moral, relational, and real.

In the biblical frame, justice is never merely about punishment. Nor is it reducible to balance. It is about alignment—a right ordering of persons, actions, and relationships under God. This means that:

The victim is not sidelined; they are honoured by being seen, heard, and acknowledged.

The offender is not merely punished; they are confronted with the truth of what they have done.

The community is not managed; it is called to participate in covenantal reckoning.

This differs from modern justice in both aim and effect. The modern court seeks resolution. Biblical justice seeks reconciliation—or, when reconciliation is refused, public exposure and separation.

As described in Appendix E6, biblical justice begins with a fourfold human framework:

Motive

Intent

Act

Outcome

But it does not end there. It moves toward a sevenfold divine reckoning, including:

Public truth-telling

Exposure of hidden intent

Recognition of ripple effects

Multiplied restitution

Final relational realignment under God's judgment

Where human systems increasingly deny even the fourfold framework, biblical justice restores both. It reclaims the moral contours of wrongdoing and carries them all the way into either restoration or judgment. It sees what was lost, demands what is due, and offers what no court can: a truth that reaches into the conscience and out into eternity.

To be clear, not every modern system is equally blind. There are echoes—sometimes faint, sometimes profound—of relational justice even within secular legal contexts:

New Zealand’s Family Group Conferences have shown how face-to-face dialogue between victim and offender can break cycles of recidivism and restore dignity.

South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission provided public moral reckoning in the wake of national trauma—imperfect, but rare in its willingness to name harm.

Yet even these efforts, noble as they are, remain vulnerable to the same simulation dynamic unless they are grounded in a true ontology. Without an account of the image of God in both victim and offender, without a recognition of sin as moral breach—not merely policy violation—these structures risk becoming performance again. They borrow the language of justice while lacking its anchoring point.

At the heart of all biblical justice is this truth: no system can replace the moral burden of the person. No institution, no policy, no code can do the work of a conscience that sees and a soul that repents.

This means that justice will always begin—and end—with persons who are willing to:

Speak truthfully even when systems incentivise silence.

Acknowledge guilt even when they could be shielded by process.

Restore what was taken, even when the law demands less.

A judge may uphold truth in a corrupt institution. A peasant may repent and restore more than was stolen. A victim may forgive—not because the system demanded it, but because the Spirit revealed the ledger in their heart.

Justice is not first a matter of structure. It is a matter of posture. And until moral agents—regardless of role or stature—bend their posture toward the truth, no system, however reformed, can enact true justice.

In the final section, we will draw these threads together and restate the foundational claim: that justice severed from ontological reality is not merely insufficient—it is inverted. It becomes injustice under the sign of justice.

Justice is not an administrative achievement. It is a moral act—a confrontation between persons, before God, grounded in what is real. When justice becomes untethered from ontology—from the real categories of truth, personhood, and moral consequence—it does not merely degrade. It inverts. It becomes a lie enacted in public, under the banner of righteousness.

This is the final tragedy of modern justice: not that it fails occasionally, but that it persists in symbolic performance while actively resisting the very thing it claims to serve. It invokes the language of truth while institutionalising avoidance. It declares restitution while delivering containment. It names equity while protecting power. And in doing so, it creates a world in which injustice flourishes under the cover of justice’s forms.

This is not merely hypocrisy. It is simulation sustained by typological theft. The forms of justice—courts, rituals, verdicts—are held up as sacred while their content is hollowed out. The typophoric referent (true justice, grounded in God’s moral order) is gone, yet the gestures continue. The result is not neutral. It is actively corrosive.

Without typological anchoring, justice becomes injustice.Without truth, even lawfulness is deception.

The recovery of justice, then, will not come through revision of systems alone. It will come through a return to the ontological order revealed by God:

Where personhood is real, because it bears divine image.

Where guilt is real, because conscience cannot be legislated away.

Where harm is real, because covenant is not a construct.

Where restoration is real, because grace is not a metaphor.

This recovery begins with moral agents who are willing to name truth at cost, to restore without demand, and to reckon with what they owe—not only before others, but before the God who keeps the final ledger.

“He hath shewed thee, O man, what is good; and what doth the Lord require of thee,but to do justly, and to love mercy, and to walk humbly with thy God?”—Micah 6:8

That verse is not sentimental. It is the prophetic collapse of all simulation. It summons each soul into the terrifying and glorious exposure of real justice. And it will stand as a witness against every system that claimed justice, but refused to enact it.