The Hegelian Dialectic did not emerge in a vacuum. It was conceived as a philosophical response to the rupture left by Immanuel Kant, who had severed reality into two realms: the phenomenal, which could be perceived, and the noumenal, which could not. In doing so, Kant left human knowledge fundamentally unmoored—capable of organizing appearances, but incapable of accessing truth in itself. Morality, too, was exiled into abstraction: obligatory, but disconnected from ontological grounding.

Into this vacuum stepped Hegel. His dialectic was not merely a speculative method—it was a moral substitute. Rather than restoring fixed revelation, he proposed that truth unfolds historically, through a triadic process: thesis, antithesis, and synthesis. Contradiction was no longer something to be judged or repented of—it was something to be subsumed, retained, and reframed within a greater conceptual unity.

This innovation carried profound consequences. Evil could now be interpreted not as rebellion, but as tension on the way to progress. Historical trauma became raw material for historical ascent. In this way, the dialectic became a secular theodicy: it preserved the appearance of moral seriousness while removing the burden of moral confrontation. The judgment seat was replaced by the process wheel.

Underlying it all was a desire to escape divine reckoning without discarding the aesthetic of transformation. The dialectic promised development without rupture, resolution without repentance, meaning without metanoia. It absorbed sin into system, and in doing so, it became an ontological evasion—a structure that mimics repentance while permanently postponing it.

What began as a metaphysical patch has become a cultural reflex. Today, the Hegelian pattern is everywhere:

Even conspiracy discourse echoes this logic with the formula: Problem → Reaction → Solution. What unites all these is the absorption of tension into process, not submission to truth. The dialectic functions as an anti-repentance machine: it simulates moral development while shielding the conscience from divine confrontation.

This appendix therefore contends that the dialectic is not just philosophically flawed—it is theologically subversive. It replaces covenant with cycle, crisis with recursion, truth with trajectory. And if it is not exposed, it will continue to shape how cultures evade God while believing they are maturing toward Him. As we will see, the impulse to neutralize moral tension through synthesis is not new. Scripture records several attempts—political, religious, and conceptual—to bypass divine confrontation through staged agreement, reframed conflict, or structural ascent. The dialectic simply codifies what fallen humanity has long attempted: reconciliation without repentance.

At its core, the Hegelian dialectic operates through a triadic mechanism:

Thesis + Antithesis → Synthesis

This structure is not merely chronological but conceptually recursive. Contradiction is not a crisis to be judged—it is the engine of progress. The synthesis does not resolve opposition in a moral sense; it elevates it to a new abstraction, preserving elements of both thesis and antithesis without repenting of either. Hegel used the term Aufhebung—“to cancel, preserve, and lift”—to describe this process of negate-and-retain.

In this model, tension is not eliminated but subsumed. There is no true resolution—only progressive recursion. And this is precisely where the danger lies: the dialectic simulates reconciliation without requiring transformation. It offers the comfort of movement without the cost of repentance.

In Daniel 11:27, we are given a striking picture of this mechanism at work: “Both these kings’ hearts shall be to do mischief, and they shall speak lies at one table; but it shall not prosper: for yet the end shall be at the time appointed.”This is not an accidental alliance—it is a theatrical one. Each party maintains contradiction internally while performing strategic unity. The table becomes a stage, not for truth, but for managed tension and narrative manipulation. It is a perfect biblical type of dialectical absorption: the opposition is preserved, not judged—suspended within a structure that postpones divine reckoning.

The same impulse is evident in Genesis 11, the account of Babel. The people unify in a synthetic project that bypasses divine order: “Let us build us a city and a tower, whose top may reach unto heaven; and let us make us a name…”(Genesis 11:4). Here, antithesis is not repented of—it is sublimated into a civilizational synthesis. Difference is flattened into unity, and tension is reconfigured as progress. But this tower is not ascent—it is evasion. The dialectic is exposed by divine descent: “The LORD came down to see the city and the tower…” (v.5), and judgment comes not by dialogue, but by disbanding.

These biblical accounts unmask the structural fraud of the dialectic: it rehearses moral categories without covenantal demand. It speaks of conflict and growth, of breakdown and resolution—but always within a frame where the self is not exposed, only reframed. It is not the conscience that is awakened—it is the concept that is advanced.

This yields a powerful ontological consequence:

The dialectic does not require the Cross—it mimics its structure while denying its necessity. Where the gospel calls for death and resurrection, the dialectic calls for iteration and reinterpretation.

In this way, the dialectic becomes a closed algorithm: it keeps moving forward, but never downward—never to the altar, never to the ground of contrition. It preserves the shape of moral movement, while replacing its substance. The dialectic resolves nothing; it reorganizes everything.

Hegel called this process Aufhebung—often translated “sublation”: to cancel, preserve, and elevate simultaneously. But functionally, this is not resolution but absorption: contradiction is not removed; it is retained and recontextualized. Sublation is the mechanism; absorption is its moral consequence.

The Hegelian dialectic does not merely manage contradiction—it reinterprets it as productive. What Hegel proposed was not a method but an ontological swap: contradiction ceases to judge the agent and instead becomes the motor of conceptual ascent.

In biblical ontology, contradiction demands resolution through judgment or repentance. But in the dialectical model, contradiction is redefined as necessary tension—a catalyst for synthesis. The clash of opposites is no longer the sign of rebellion; it is reframed as the raw material for conceptual ascent.

This is the ontological swap: contradiction ceases to be a crisis and becomes the engine of convergence. Evil is not opposed by holiness—it is repurposed within a structure that promises transformation without rupture. Truth is no longer a dividing line—it becomes a developmental trajectory. This inversion disables moral discernment. What should be named and forsaken is now retained and reframed.

We see a foreshadowing of this inversion in Mark 12, when Jesus asks the religious leaders: “The baptism of John, was it from heaven, or of men?” (v.30). Their response is not to seek truth, but to manage optics: “If we shall say, From heaven; he will say, Why then did ye not believe him? But if we shall say, Of men; they feared the people…” (vv.31–32). Their refusal to choose exposes the dialectical instinct: preserve both positions, avoid exposure, and maintain the illusion of synthesis. But Jesus does not allow dialectic; He forces disambiguation: “Neither do I tell you…” (v.33). Silence replaces synthesis. The game is judged.

Likewise, in John 18–19, we see a dialectical theater unfold around Christ’s trial. Pilate seeks to avoid moral commitment by oscillating between thesis and antithesis: “What is truth?” (John 18:38), he asks—then proceeds to declare Jesus innocent while authorizing His death. The religious leaders invoke Caesar while denying their Messiah. The crowd cries “We have no king but Caesar” (19:15), synthesizing the unthinkable to preserve their position. Here, contradiction is not resolved—it is collaged. But the cross exposes every evasion. Divine judgment pierces the dialectic.

This is why the dialectic is not just a model—it is an ontological danger. It replaces submission with synthesis. It teaches the soul to reinterpret moral tension instead of repenting of it. The agent is no longer called to bow—he is invited to reframe.

Thus:

This is not sanctification—it is simulation. It retains the outer form of transformation but removes the inner work of surrender. In so doing, it offers the pattern of moral progress without the Person who alone grants it.

To accept contradiction as fruitful is to renounce the call to cruciform judgment. The dialectic says, “Transform through convergence.” The gospel says, “Die, and be made new.”

A crucial distinction must be made explicit in order to understand why the Hegelian dialectic does not merely err, but structurally evades truth. This distinction is between constraint conditions and boundary failure modes.

A constraint condition is a non-negotiable limit imposed by reality itself. It marks what cannot be the case, what may not be affirmed, and what must be refused regardless of narrative, intention, or process. Ontological constraints delimit what can exist; epistemic constraints delimit what can be known; moral constraints delimit what may be enacted. In a constrained ontology, contradiction is not productive tension but evidence of misalignment. It demands judgment, correction, or repentance.

A boundary failure mode, by contrast, is not a limit but a symptom. It is what becomes visible when a constraint condition is violated or denied. Cognitive dissonance, moral incoherence, abstraction escalation, and pseudo-resolution are not boundaries themselves; they are the experiential or systemic consequences of crossing boundaries that reality does not relax. Boundary failure modes expose refusal, but they do not define reality’s limits.

The defining operation of the dialectic is the systematic collapse of this distinction. Rather than allowing constraint violations to count as refusal, the dialectic reclassifies boundary failure modes as legitimate developmental inputs. Contradiction is not treated as a signal that something must be rejected, but as evidence that a higher synthesis is required. The boundary does not refuse; it merely “pressurizes” the system toward further abstraction.

This reclassification explains why the dialectic cannot exclude anything in principle. Because constraint conditions are never allowed to function as limits, nothing can finally fail—only reposition itself within the process. Error is not eliminated but absorbed. Falsehood is not judged but reframed. Rebellion is not named but metabolized. What should function as ontological refusal is converted into procedural momentum.

In biblical ontology, boundary failure is meaningful precisely because constraints are real. Contradiction signals not creative tension but moral rupture. Truth confronts; it does not synthesize with its negation. Repentance, not incorporation, is the path to restoration. The dialectic reverses this grammar entirely: it preserves contradiction by neutralizing the very category of refusal.

Seen in this light, the dialectic is not a worldview competing with others, but an abstraction engine that dissolves all worldviews by disabling constraint. It does not ask whether a claim aligns with reality; it asks only whether it can be incorporated without collapsing the system. The result is not reconciliation, but unlimited admissibility—motion without judgment, coherence without truth.

The greatest danger of the dialectic is not its complexity—it is its capacity to soothe the conscience while bypassing repentance. It offers a counterfeit version of conviction: emotional movement without moral rupture. The agent is not confronted but absorbed. Guilt is not exposed and healed—it is reframed and deferred. The dialectic offers relief, not reckoning.

In this system, moral language is retained while its ontological demands are emptied. Justice becomes developmental. Holiness becomes aspirational. Evil becomes pedagogical. The soul is taught to think in terms of progress rather than purity, in phases rather than confrontation. In this way, the dialectic performs a conceptual anesthesia—a softening of the moral register under the guise of intellectual growth.

This mirrors the accusation in Isaiah 59: “Justice is turned back, and righteousness stands afar off; for truth is fallen in the street, and equity cannot enter” (v.14). The prophet describes not merely the absence of virtue, but its systemic distortion—where categories remain, but their referents are displaced. Truth is not denied—it is neutralized. Conscience is not slain—it is sedated.

A similar mechanism appears in Matthew 4, where Satan offers Jesus the kingdoms of the world without the cross. He proposes a shortcut—an ontological synthesis: retain the appearance of dominion without the cost of obedience. It is the dialectic in its most distilled form: glory without suffering, resolution without rupture, ascent without descent. But Christ does not negotiate—He rebukes. The contradiction is not managed; it is cast down.

This exposes the theological counterfeit at the heart of the dialectic. It mimics sanctification while excluding its necessary elements: confrontation, confession, and covenantal submission. It produces the form of brokenness but avoids its implications. The dialectic is not the path of crucifixion—it is the escalator of reinterpretation.

Thus:

This is not maturation—it is deferral. It offers the vocabulary of growth without the grammar of surrender. The dialectic becomes a theological sedative, inoculating the conscience against the urgency of divine voice: “Today, if you hear His voice, do not harden your hearts” (Hebrews 3:15). The dialectic is not the resolution of contradiction but the refusal to let contradiction accuse.

By perpetually interpreting rather than repenting, the soul is left in an intellectual rehearsal of transformation, never touched by grace. The dialectic says: “Synthesize your tension.” The Spirit says: “Repent and live.” The Cross is not a synthesis; it is a judgment. It does not reconcile contradiction by reframing it but by crucifying it.

The dialectic did not die with Hegel—it metastasized. Modernity did not adopt Hegelian terminology; it adopted Hegelian reflexes. Adopted by Marx, stylized by continental philosophy, and absorbed into Western consciousness, the triadic pattern became the structural reflex of cultural formation. It no longer needed to be invoked explicitly. It was simply enacted.

In modern protest movements, contradiction is preserved for dramatic tension, not resolved by submission to truth. Opposition is stage-managed. Outrage is aestheticized. The dialectical cycle thrives not by achieving moral clarity, but by converting polarization into spectacle—controlled synthesis masquerading as social evolution.

This same pattern can be traced back to Genesis 11. The Tower of Babel was an act of convergence—“Come, let us build… lest we be scattered.” It was a synthetic unity based not on truth or covenant, but on self-preservation and technocratic ambition. The people did not repent—they fused. The judgment of God came not for disorder, but for simulated order: a false unity that defied ontological distinction. Babel is not the chaos of contradiction—it is the pseudo-resolution of it.

In the New Testament, the dialectical logic reappears in John 18–19. Pilate, confronted with Christ—the Truth incarnate—tries to synthesize opposing forces: public pressure, Roman authority, his own unease. He seeks resolution through ritual: “Behold the man… Shall I crucify your king?” The crowd answers with its own dialectical inversion: “We have no king but Caesar.” In this moment, divine judgment is not denied but reframed as political expediency. The confrontation of righteousness is neutralized through institutional synthesis.

Mark 12 presents yet another echo: when Jesus is questioned by Pharisees and Herodians—an unlikely alliance—He unmasks their dialectical trap. They pretend to pose a moral dilemma about taxes, but their aim is not truth, but entrapment. Christ does not negotiate the antithesis—He exposes the premise. “Render unto Caesar… and unto God…”He splits their synthetic gesture by reasserting ontological priority.

These examples show that the dialectic is not just a theory—it is a counterfeit liturgy of history. It absorbs truth into performance, contradiction into process, and moral crisis into cultural choreography. It becomes the operating system of spectacle: protest as branding, repentance as vibe, justice as commodity.

Even modern theology has not escaped. The rise of the “radical middle”—balancing conviction and relevance, holiness and inclusion—is often a dialectical fusion rather than a return to fidelity. The Cross becomes a backdrop, not a crossroads. The gospel is not denied—it is recast as a mood.

In all these cases, the dialectic offers the comfort of tension without the offense of truth. It choreographs conflict into convergence without confrontation. It baptizes the crowd’s desire to feel unified while shielding it from the summons to kneel.

The result is not peace—but sedation. Not reformation—but recursion. The dialectic persists not because it is true, but because it flatters every institution that fears moral rupture.

It is not the grammar of Gethsemane—but the grammar of consensus. And it leaves the conscience unpierced, though surrounded by ritual.

The Hegelian dialectic frames contradiction as a generative tension—a necessary polarity from which truth emerges. But this reframing is not neutral. It is a reprogramming of reality. For in the biblical and submetaphysical view, contradiction is not the womb of synthesis—it is the evidence of moral rupture. It signals a crisis demanding confrontation, not recursion.

Scripture consistently treats contradiction as exposure. When light confronts darkness, the result is not fusion—it is judgment (John 3:19–21). When Elijah faces the prophets of Baal, there is no synthesis—there is fire. When Jesus declares He came not to bring peace but a sword (Luke 12:51), He affirms that truth disambiguates. It divides the soul from its self-justifying strategies. It does not blur—it separates.

Submetaphysically, contradiction is a test of posture. It reveals whether the agent will submit to ontological reality or reframe it through cognitive recursion. In this sense, the dialectic is not merely an epistemological error—it is an ontological rebellion. It replaces the crisis of truth with the comfort of process. It reassigns the role of judgment from God to history.

But moral growth does not occur through synthesis. It occurs through rupture—repentance, surrender, death to self. Contradiction, rightly understood, should bring the soul to the brink—not to a conceptual elevation, but to the threshold of repentance. This is why biblical confrontation is so disruptive: it does not offer perspective-shifting—it demands allegiance.

The dialectic, by contrast, anesthetizes. It allows the agent to feel sophisticated while avoiding submission. It retains the tropes of development—transcendence, elevation, evolution—while evacuating the cost of truth. It turns judgment into pedagogy, righteousness into aspiration, sin into tension.

Submetaphysics restores the fundamental coordinates:

In light of this, the dialectic must be unmasked not simply as a mistaken method, but as a counterfeit metaphysical grammar. It reassigns the deep structures of being—reality, perception, rationality, and personhood—into an algorithm of infinite delay. It simulates moral movement while tethering the conscience to an ever-receding horizon of “progress.”

This is not growth. It is evasion. And unless the agent bows before the dividing Word—“sharper than any two-edged sword” (Hebrews 4:12)—the cycle will continue. Syntheses will pile upon syntheses, but no judgment will come. Until at last, it does.

For in the end, there is no dialectic at the Judgment Seat. There is no synthesis—only truth.

The Hegelian dialectic is not merely an intellectual framework—it is a spiritual sedative and a cultural algorithm. It absorbs moral contradiction into conceptual progression, shielding the soul from divine confrontation while simulating transformation. It reframes evil as developmental, judgment as premature, and repentance as unnecessary. In doing so, it offers the comfort of movement without the cost of surrender.

But biblical truth does not spiral—it divides. It does not synthesize—it severs. “Do not think that I came to bring peace,” said Christ, “but a sword” (Matthew 10:34). The sword of truth does not accommodate contradiction—it exposes it. The dialectic, by contrast, reinterprets rebellion as necessary tension, and replaces the summons to kneel with the invitation to reframe.

This appendix has shown that the dialectic is not a neutral tool—it is an ontological counterfeit. It offers reconciliation without rupture, healing without holiness, synthesis without sacrifice. And for this reason, it must not merely be understood—it must be unmasked.

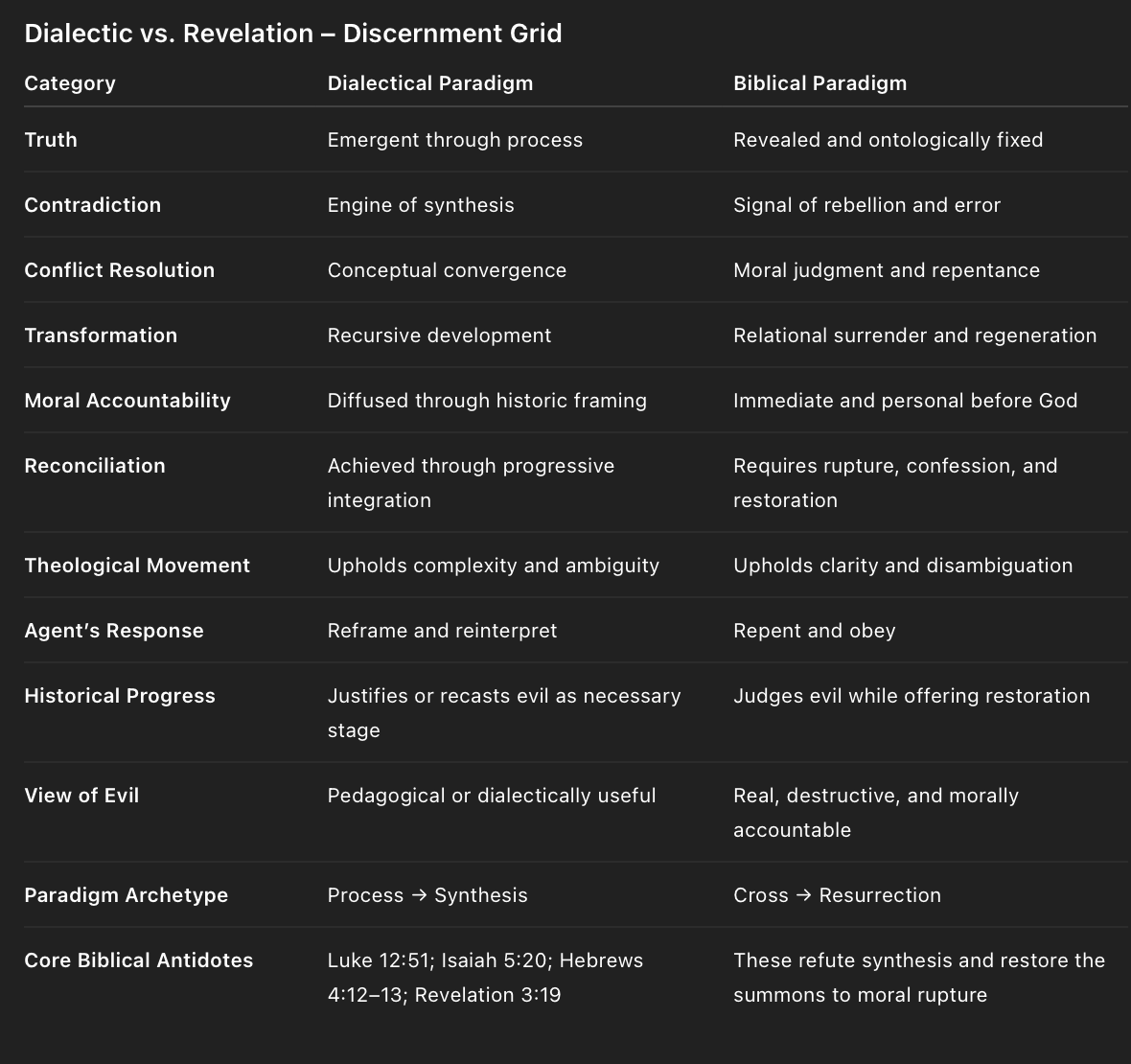

To aid the reader in this task, a Discernment Grid is provided at the close of this appendix, summarizing the contrast between the dialectical paradigm and biblical revelation. It is offered not as a philosophical exercise, but as a spiritual safeguard—for the soul that still hears the voice saying, “Today, if you hear His voice, do not harden your heart.”

Legend:

Dialectical Column:

Represents the interpretive and moral logic of the Hegelian dialectic, in which contradiction is assimilated

and moral categories are dissolved through process.

Biblical Column:

Represents the ontological and covenantal structure of divine revelation, in which contradiction is exposed, judged,

and resolved through repentance and submission.

Each row contrasts a core epistemic or ontological category to show how the dialectic subtly inverts or neutralizes biblical demands. How to use: This grid is not exhaustive, but diagnostic. It is designed to assist readers in identifying dialectical patterns—whether in culture, theology, or personal reasoning—that simulate transformation while avoiding surrender.

Footnote

Modern politics is not governed by conviction or truth-alignment, but by a dialectical logic in which positions exist to generate tension, coalitions exist to absorb contradiction, and allegiance matters more than belief.