Most Christian explanations of the cross begin at the level of effect. They speak of what Christ’s death accomplished—how “through death he might destroy him that had the power of death, that is, the devil” (Hebrews 2:14); how it “abolished death, and hath brought life and immortality to light through the gospel” (2 Timothy 1:10); or how it “reconciled the world unto God” (2 Corinthians 5:19). Yet these describe the fruits, not the fountain, of redemption. Valid as they are, they concern what followed from Calvary, not what made it necessary.

To understand why Jesus had to die, we must look beneath events to the very order of being and government—to the nature of God, the moral architecture of His creation, and the disorder introduced by sin. The answer cannot rest in divine fiat, “for God is not a man, that he should lie” (Numbers 23:19), nor could He arbitrarily choose blood instead of pardon, for “the LORD is righteous in all his ways, and holy in all his works” (Psalm 145:17). The necessity rests in the nature of holy love—that indivisible harmony of justice, mercy, and truth by which God sustains both His being and His government. “Justice and judgment are the habitation of thy throne: mercy and truth shall go before thy face” (Psalm 89:14).

While the language of being and government describes the structure of reality, Scripture itself reveals that structure through covenantal and moral terms—righteousness, faithfulness, mercy, and truth. These are not abstractions but the living fabric of divine life, by which God both governs creation and discloses His nature in redemption.

This harmony forms the moral foundation of the universe. God’s rule must remain transparently righteous before every moral intelligence, “that thou mightest be justified when thou speakest, and be clear when thou judgest” (Psalm 51:4). The rebellion of sin therefore raised not only a human crisis but a cosmic question: Can divine love remain holy without permitting moral disorder? Could mercy be shown without unseating justice? In short, could the divine government stand vindicated before unfallen worlds and angelic hosts (cf. 1 Peter 1:12; Revelation 5:11–13)?

Thus, by hypothetical necessity—that is, necessity consequent upon God’s will to redeem without violating His holiness or undermining the confidence of unfallen intelligences—only the divine yet unfallen, law-transcendent, and impartial Son could restore both creation and moral order. His death was not an episode of wrath but the ontologically and judicially coherent act wherein love and justice met without contradiction: “mercy and truth are met together; righteousness and peace have kissed each other” (Psalm 85:10).

The cross therefore concerns more than man’s salvation: it upholds the integrity of God’s throne and the moral intelligibility of the universe. Our task is to discern, in the structure of being and of divine government alike, why there was no other way.

In this essay Godhead denotes the plenitude of divine nature (theotēs, Col 2:9) rather than the Nicene concept of three co-equal persons. The Son shares the Father’s divine kind through begetting, not co-eternal symmetry—substantive ontohomogeneity with distinct ontorelationality. See Appendix A for a detailed discussion.

Sin, in its essence, is more than the breaking of a commandment; it is the rupture of being. Scripture declares, “All we like sheep have gone astray; we have turned every one to his own way” (Isaiah 53:6). This turning from the Life-Giver is not merely moral rebellion—it is the sundering of the creature from the very Source of life. The act of disobedience in Eden did not simply incur penalty; it altered ontology. God had warned Adam, “In the day that thou eatest thereof thou shalt surely die” (Genesis 2:17). The words were not threat but description: separation from the Creator would of itself dissolve the created order of life.

Thus, death is not first a judicial sentence; it is the natural and ontological outcome of rebellion. “For the wages of sin is death” (Romans 6:23). The soul that departs from God departs from life. Sin carries within itself the principle of dissolution; it is entropy within the moral fabric of creation. Humanity, designed for communion, became inwardly fragmented—disconnected from God, from one another, and from the harmony of creation itself.

This rupture reverberated through the entire moral universe. The fall of man did not merely corrupt the earth; it introduced a principle of doubt regarding the righteousness of divine government. If the first created beings could sin under a perfect ruler, what assurance had the unfallen hosts that the divine order was incorruptible? Satan’s accusation—implied in his rebellion—was that God’s law was arbitrary, that His government was self-serving, and that love and justice could not coexist.

Hence, forgiveness by mere decree could not resolve the question. To simply overlook sin would have confirmed the adversary’s charge that God’s law was flexible or unjust. The universe required demonstration that divine mercy did not annul divine order. “The LORD is righteous in all his ways, and holy in all his works” (Psalm 145:17). If moral order was to be restored, it must be done from within the fallen realm, by One who could both share the consequences of rebellion and yet remain untainted by it. Such a work demanded a Mediator who could reach across the ontological chasm between Creator and creature, bringing back into harmony what sin had torn apart.

To understand why only the death of the Son of God could accomplish this restoration, we must first grasp what may be called the Divine Double Prerogative—the Father’s exclusive rights as both Author of Being and Governor of Moral Order. (See Ontology part I for a detailed discussion).

Auctoritas Essendi — the Authority of Being. “For with thee is the fountain of life” (Psalm 36:9). God alone possesses underived existence: “For as the Father hath life in himself; so hath he given to the Son to have life in himself” (John 5:26). Every created life is contingent upon His will. When the creature severs itself from God, it forfeits the conditions of its own being. No created agent can restore what only the Source of life can bestow.

Auctoritas Instantiandi — the Authority to Reinstantiate Moral Reality. God alone can call into existence new moral order or reconstitute a defiled one. “See now that I, even I, am he, and there is no god with me: I kill, and I make alive; I wound, and I heal” (Deuteronomy 32:39). This prerogative belongs to none but the Creator. Therefore, after sin entered, no creature—however penitent—could re-create righteousness within itself or the universe.

The problem of restoration thus transcends human guilt; it reaches into the integrity of God’s own rule. The universe could not be reconciled through mere indulgence without violating the very principles on which divine government rests. Justice must remain unbending, for “righteousness and judgment are the habitation of thy throne” (Psalm 97:2). At the same time, love yearned to redeem the lost, “not willing that any should perish, but that all should come to repentance”(2 Peter 3:9).

Only one could reconcile these two prerogatives: the begotten Son, who shares the Father’s nature and authority yet is capable of entering creation as man. “For there is one God, and one mediator between God and men, the man Christ Jesus” (1 Timothy 2:5). As divine, He exercises the Father’s power to re-create; as human, He represents the fallen race in filial obedience. His incarnation is therefore not an afterthought of mercy but the ontological bridge between holiness and compassion.

In Him, both prerogatives meet. The Father’s right to sustain being and the Father’s right to govern righteousness are manifested in filial form. The Son, as the living expression of divine government, must enter the very domain where rebellion had erupted, bearing within Himself the full truth of God’s justice and the full mercy of His love. That union could be consummated only through death—for the disorder of sin had penetrated to the roots of being, and only by yielding life itself could it be undone.

If sin shattered the fabric of being, the repair must proceed in two directions—Godward and manward—for the breach lay between Creator and creature. Scripture joins these movements under the twin realities of propitiation and expiation.

Propitiation (Godward)

“Whom God hath set forth to be a propitiation through faith in his blood, to declare his righteousness for the remission of sins that are past” (Romans 3:25). The Son offers Himself as the filial and priestly gift that honours the Father’s holiness, satisfies divine justice, and vindicates the rectitude of His government before all intelligences. “It became him, for whom are all things, and by whom are all things, … to make the captain of their salvation perfect through sufferings” (Hebrews 2:10). “He is the propitiation for our sins: and not for ours only, but also for the sins of the whole world” (1 John 2:2; cf. 1 John 4:10). This is not placation of anger but the public revelation that mercy operates only within the truth of righteousness.

Expiation (Manward)

The same blood that upholds God’s honour cleanses man’s defilement: “How much more shall the blood of Christ, who through the eternal Spirit offered himself without spot to God, purge your conscience from dead works to serve the living God?” (Hebrews 9:14). Expiation removes not merely guilt but corruption; it purges the conscience and re-enables communion with God. Thus humanity is made a vessel fit for the indwelling life of the Spirit.

Integration of both

Propitiation restores divine order; expiation restores creaturely capacity. The two are one act: the cross displays before heaven and earth that “the LORD is righteous in all his ways, and holy in all his works” (Psalm 145:17), while simultaneously making sinners righteous through participation in that holiness.

Priestly–covenantal bridge

Christ fulfils and transcends the Levitical pattern. “We have such an high priest, who is set on the right hand of the throne of the Majesty in the heavens” (Hebrews 8:1). In His blood the old covenant finds completion, and the new is ratified: “This is my blood of the new testament, which is shed for many for the remission of sins” (Matthew 26:28).

For such a sacrifice to possess redemptive sufficiency, the Offerer Himself must meet conditions that no created being could fulfil.

Pre-incarnational non-subjection to law

Before His incarnation the Logos stood above the moral economy He had Himself ordained. He was the Law-giver, not the law-bound: “For the LORD is our judge, the LORD is our lawgiver, the LORD is our king; he will save us”(Isaiah 33:22). In assuming human nature, “made of a woman, made under the law, to redeem them that were under the law” (Galatians 4:4–5), He voluntarily entered a system to which He owed no obedience. Because His life was not forfeit, His obedience carried ontological surplus value—it was not remedial but creative, the founding act of a new humanity.

Incarnation as legitimate representation

Scripture forbids one man to bear the iniquity of another: “The soul that sinneth, it shall die. The son shall not bear the iniquity of the father” (Ezekiel 18:20). Likewise, “None of them can by any means redeem his brother, nor give to God a ransom for him” (Psalm 49:7). Human substitution is morally inadmissible; every accountable being must answer for itself. Therefore, if redemption were to occur, it required a Person who was truly human, to stand within the race, yet free from its indebtedness, to act as its representative. This is the mystery and necessity of the incarnation: God entering humanity so that, as man, He might justly bear what no other man could.

Sinlessness and unfallen humanity

“For such an high priest became us, who is holy, harmless, undefiled, separate from sinners” (Hebrews 7:26). Though “in all points tempted like as we are, yet without sin” (Hebrews 4:15), He never incurred guilt. Thus He could bear sin vicariously without sharing its culpability.

Filial authority and representational legitimacy

As the begotten Son He possesses the Father’s prerogative over life and being: “For as the Father raiseth up the dead, and quickeneth them; even so the Son quickeneth whom he will” (John 5:21). As the Son of Man He lawfully stands in Adam’s stead: “For as in Adam all die, even so in Christ shall all be made alive” (1 Corinthians 15:22). Only the incarnate Son unites divine authorship and human accountability in one Person.

Summary

Incarnation is therefore the indispensable condition of legitimate substitution. No mere creature could die for another when “the soul that sinneth, it shall die” (Ezekiel 18:20); but He who became man without ceasing to be God could stand in man’s place without transgressing the moral order He came to uphold. In Him, representation is no fiction—it is ontological reality.

Even a perfect offering would fail if its motive were self-referential. The moral beauty of the cross lies in the impartiality of its love.

Disinterested benevolence

“Greater love hath no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends” (John 15:13); yet Christ’s love reached beyond friendship to enmity: “While we were yet sinners, Christ died for us” (Romans 5:8). His self-giving was neither tribal nor selective; it flowed from divine nature itself—love acting from fullness, not from need.

Freedom of motive

Because He was under no compulsion—“No man taketh it from me, but I lay it down of myself” (John 10:18)—His sacrifice was morally free and universally fitting. Love and liberty met in one voluntary act.

Ontic significance of love

“God is love” (1 John 4:8); therefore love is not sentiment but substance—the very form of divine being. In the cross, that being is made visible: the eternal nature expressing itself through self-emptying. Hence the atonement is ontologically beautiful because it is morally pure.

Impartial origin and particular application

The motive is universal—“God so loved the world” (John 3:16)—but its administration is historically particular, extending covenantally to those who believe. The impartiality secures the justice of His government; the particularity preserves the reality of faith and repentance (Acts 17:30; Romans 3:26).

Having entered humanity as its rightful representative, the Son must carry the act of obedience to its uttermost—unto death. For the moral breach of sin had penetrated to the roots of being; life itself must be yielded to reverse the corruption of life itself.

The life is in the blood

The divine principle is plain: “For the life of the flesh is in the blood: and I have given it to you upon the altar to make an atonement for your souls: for it is the blood that maketh an atonement for the soul” (Leviticus 17:11). In biblical idiom, blood represents life offered back to God. To heal a rupture of being, being itself must be surrendered in filial trust.

Why death, not mere suffering, was required

Suffering may reveal obedience, but death consummates it. “He became obedient unto death, even the death of the cross”(Philippians 2:8). Since “the wages of sin is death” (Romans 6:23), restoration demanded that the innocent Life voluntarily enter the domain of death and there undo its hold. “Without shedding of blood is no remission” (Hebrews 9:22). Death is not incidental to atonement; it is its very form.

Necessity qualified

This was not metaphysical compulsion upon God, but what the older theologians called necessitas consequentiae: once God wills to save sinners without falsifying His holiness, the cross becomes the only act consistent with His nature. “It became him, for whom are all things, … in bringing many sons unto glory, to make the captain of their salvation perfect through sufferings” (Hebrews 2:10).

Covenantal ratification

Death is also the covenantal seal: “For where a testament is, there must also of necessity be the death of the testator”(Hebrews 9:16). Thus the blood of Christ inaugurates the New Covenant—“This is my blood of the new testament, which is shed for many for the remission of sins” (Matthew 26:28).

Through death, therefore, Christ satisfies both the ontological necessity of life yielded and the juridical requirement of covenant ratification. The cross is the hinge of both being and government.

1. The Veiling of Deity

Some have reasoned that divinity and death are incompatible—that if Christ truly died, He could not have been God. Yet this rests on a categorical confusion: it mistakes the conditions of divine participation for the loss of divine nature. The incarnation was not the abdication of deity but its veiling within humanity: “Forasmuch then as the children are partakers of flesh and blood, he also himself likewise took part of the same” (Hebrews 2:14).

In assuming human nature, the eternal Word did not cease to be God; He entered the domain where death reigned, that through death He might abolish it. Death reached His humanity, not His Godhead. The Life-Giver could not die in essence, but in true union with human nature He could yield that life in form, allowing mortality to exhaust itself upon what is immortal. Thus, the cross is not evidence of divine absence but the theatre of divine presence—the infinite stooping to heal the finite from within.

2. The Emptying of Prerogative and the Curriculum of Temptation

Here the mystery of kenōsis and tapeínōsis is revealed in full. He “emptied Himself” (Philippians 2:7) not by divesting Himself of deity, but by expressing it through self-giving love. He “humbled Himself” (Philippians 2:8) not by ceasing to reign, but by translating sovereignty into obedience. In kenosis, divine fullness consents to limitation; in tapeinosis, divine majesty consents to suffering. Both are not negations but manifestations of what God eternally is: love acting in truth.

To enter our condition fully, He also emptied Himself of divine prerogatives—the independent exercise of power and the immunity of omniscience. He chose instead to live as man under the Spirit’s guidance, submitting to the same moral curriculum that confronts every soul. “Though he were a Son, yet learned he obedience by the things which he suffered” (Hebrews 5:8). Tempted in all points as we are, yet without sin (Hebrews 4:15), He proved that holiness can subsist under human limitation when wholly dependent upon the Father. His victory was not by exemption but by trust; not by inherent advantage but by perfect faith. Thus the kenosis was complete—not the emptying of divinity, but the refusal to exploit it.

3. The Authority to Lay Down Life

Yet even in this descent, the Son acted not under compulsion but by right. “No man taketh it from me, but I lay it down of myself. I have power to lay it down, and I have power to take it again. This commandment have I received of my Father” (John 10:18). The cross was therefore not only the consent of humility but the exercise of divine permission. The Son’s authority to yield life flowed from the Father’s own auctoritas essendi—the authority of being—shared with Him in filial trust. Thus, the obedience of Christ was never servile; it was sovereign submission—the lawful self-offering of the Life-Giver within the bounds of divine government.

In Him, freedom and obedience, authority and surrender, were perfectly one. The kenotic and tapeinotic acts together constitute the ontological revelation of divine nature under the conditions of finitude. What appeared humiliation was in truth manifestation—the eternal love of God shown not above suffering, but within it.

4. The Garb of Humanity and the Revelation through Concealment

In the language of faith, divinity was “veiled with humanity.” Scripture affirms that “the Word was made flesh, and dwelt among us” (John 1:14), and that “in Him dwelleth all the fulness of the Godhead bodily” (Colossians 2:9). The veil was real, but it concealed glory—it did not subtract it. As the ancient sanctuary hid the shekinah behind a curtain of woven fabric, so the humanity of Christ covered divine majesty that it might draw near without consuming. The “garb of humanity” was therefore the form through which infinite holiness could be revealed to finite sight. In Him, concealment was revelation—the light of God shining through the humility of man.

Thus, the death of Christ does not contradict His deity—it discloses it. Only God could so descend without ceasing to be Himself; only omnipotence could so fully consent to weakness without forfeiting power. Were He not God, His death would be defeat; because He is God, it becomes victory—the Life entering death, truth entering falsehood, light entering darkness, and in so doing, consuming them. The cross is therefore the final unveiling of divine prerogative within human form: majesty revealed as meekness, power as peace, and sovereignty as self-giving love.

Once the ontological necessity was fulfilled in death, the Father answered with resurrection—the divine ratification and public vindication of the Son’s work. What follows are not causes of redemption but its fruits and demonstrations.

Resurrection as ontological ratification

“Who was delivered for our offences, and was raised again for our justification” (Romans 4:25). The resurrection proves that the atonement satisfied the claims of both law and life. It is the visible affirmation that righteousness has prevailed and the curse is reversed. The resurrection is not an appendix to the cross; it is its unveiling in light.

Destruction of Satan’s dominion

“That through death he might destroy him that had the power of death, that is, the devil” (Hebrews 2:14). The adversary’s jurisdiction rested upon accusation—law broken, justice unsatisfied. “Blotting out the handwriting of ordinances that was against us … nailing it to his cross” (Colossians 2:14). When the incarnate Son fulfilled every demand, that ground was removed, and the accuser was silenced. “Having spoiled principalities and powers, he made a shew of them openly, triumphing over them in it” (Colossians 2:15).

Deliverance of captives

“When he ascended up on high, he led captivity captive, and gave gifts unto men” (Ephesians 4:8). Those once bound under death’s dominion are reclaimed under the authority of the risen Christ. Resurrection proclaims liberty to the captives; it is the lawful exodus of the redeemed.

Abolition of death

“Our Saviour Jesus Christ … hath abolished death, and hath brought life and immortality to light through the gospel” (2 Timothy 1:10). Death, now under Christ’s keys (Revelation 1:18), becomes temporary sleep for the believer—no longer domain of separation but vestibule of resurrection.

Headship of the new creation

“Who is the beginning, the firstborn from the dead; that in all things he might have the preeminence” (Colossians 1:18). The risen Christ is both the pattern and the power of renewed existence. What was accomplished in Him ontologically will be extended eschatologically to His body, the Church.

Thus the resurrection is God’s public declaration that His government remains righteous, His love victorious, and His creation secure.

The cross reconciles what human reasoning cannot—justice and mercy, truth and love—because it arises not from external decree but from the inner nature of God.

Harmony of divine attributes

“Justice and judgment are the habitation of thy throne: mercy and truth shall go before thy face” (Psalm 89:14). At Calvary, these attributes converge. Justice is not suspended for mercy; mercy operates within justice. The law is not relaxed but fulfilled.

Integration of atoning dimensions

Propitiation restores Godward order, declaring His righteousness before the universe.

Expiation heals human participation, purging conscience and enabling communion.

Qualification ensures legitimacy—the Offerer is both divine and human.

Impartial love ensures moral fitness—the act is disinterested and therefore universal.

Resurrection seals and displays the accomplishment.

Together these dimensions reveal the unity of divine government and the restoration of ontology.

Rebuttal of cosmic accusation

The cross answers every question raised by rebellion: whether divine government is just, whether love can coexist with law, whether God can forgive without contradiction. In Christ all such doubts expire. “That thou mightest be justified when thou speakest, and be clear when thou judgest” (Psalm 51:4).

Perfection of moral government

The universe now beholds that God’s rule is neither arbitrary nor lenient but self-consistent. Calvary stands as the eternal demonstration that the throne of God is founded upon righteousness and maintained by love.

In the light of the cross, ontology and government, being and justice, holiness and mercy, form one indivisible truth: “God is light, and in him is no darkness at all” (1 John 1:5).

When all is seen in the light of revelation, the death of Christ appears not as the tragedy of an age but as the inevitable expression of divine love under moral necessity. The cross stands where the structure of being and the order of government converge—where mercy and justice meet in unbroken harmony.

The Scriptures bear united witness that God’s purpose was neither arbitrary nor reactive. “Known unto God are all his works from the beginning of the world” (Acts 15:18). The plan of redemption was foreseen because love is the foundation of all divine action: “God is love” (1 John 4:8). Yet love cannot act lawlessly without ceasing to be holy. When rebellion entered the moral universe, love must either deny itself or fulfil its own righteousness through self-sacrifice.

It was not without divine sorrow that the Father gave His only-begotten Son, nor without filial willingness that the Son accepted the charge. The Father “spared not his own Son, but delivered him up for us all” (Romans 8:32); and the Son declared, “Lo, I come to do thy will, O God” (Hebrews 10:7; cf. John 6:38). Thus, the cross was neither imposed nor resisted—it was the voluntary union of the Father’s holiness and the Son’s obedience, the only act consistent with the righteousness of God and the stability of His government.

In that act, every question raised by sin found its answer. The adversary had charged that divine government was self-seeking and unjust; Calvary revealed a God who would rather suffer wrong than inflict it unjustly. “Hereby perceive we the love of God, because he laid down his life for us” (1 John 3:16). The integrity of the law was vindicated; the goodness of the Law-giver was unveiled. The universe beheld that truth and love are not opposing forces but one eternal reality manifest in the Son.

The necessity of the cross is therefore ontological—rooted in the nature of God Himself. Once the divine will purposed to redeem without violating holiness, there remained only one path: the way of self-giving love. It was the necessitas consequentiae of holiness and mercy in perfect union. “For it became him, for whom are all things, and by whom are all things, … to make the captain of their salvation perfect through sufferings” (Hebrews 2:10). Only such an act could restore the harmony of the universe and secure the allegiance of all moral intelligences throughout eternity.

Therefore the cross is not a symbol of defeat but of divine sovereignty. It upholds the throne of God as both righteous and gracious, fulfilling the ancient psalm: “Mercy and truth are met together; righteousness and peace have kissed each other” (Psalm 85:10). Every redeemed being, every unfallen world, every angelic host now beholds that the government of God is founded upon self-sacrificing love and maintained by incorruptible justice.

In this light, the declaration of Christ gains eternal weight: “And I, if I be lifted up from the earth, will draw all men unto me” (John 12:32). The cross is the gravitational centre of moral reality, drawing the universe back into alignment with its Creator. There, divine prerogative and human participation are reconciled; there, love proves itself the law of life.

Henceforth all being rests secure in the knowledge that God’s rule is not tyranny but truth, not compulsion but communion. Calvary stands as the everlasting witness that holy love governs the universe, and that in the Son’s obedience unto death, being itself has been healed. What began as question ends as revelation:

“Worthy is the Lamb that was slain to receive power, and riches, and wisdom, and strength, and honour, and glory, and blessing” (Revelation 5:12).

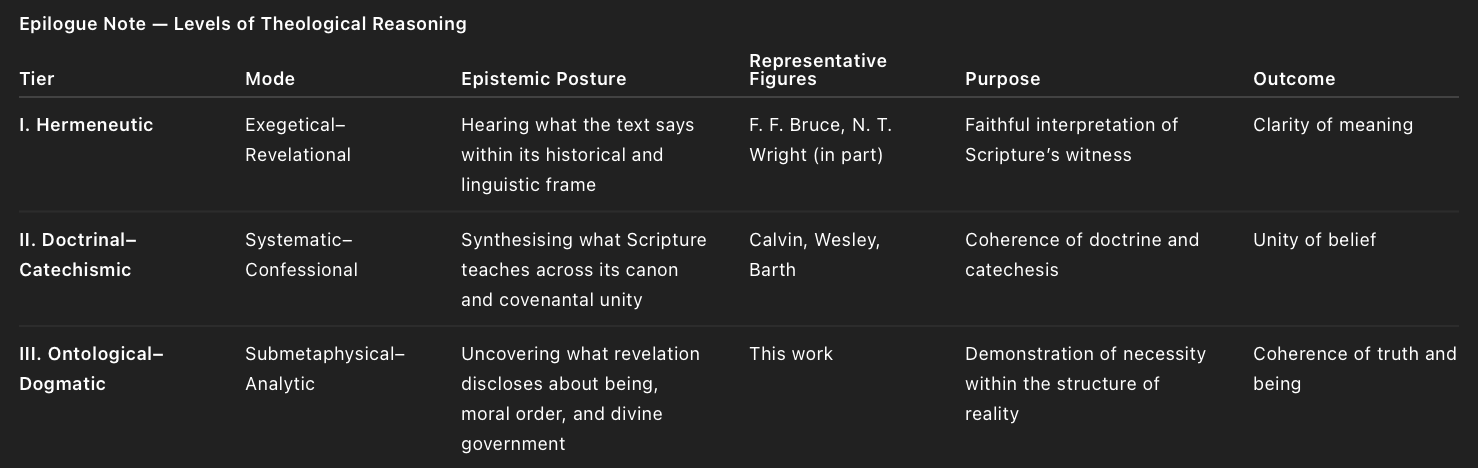

The argument advanced in this essay proceeds beyond description to demonstration. It assumes the labours of the exegete, who establishes what Scripture says, and of the theologian, who harmonises what it means. Yet its distinct task has been to uncover what Scripture reveals about the structure of being itself—why divine love, justice, and government could meet in no other act than the cross.

This movement from text to truth, from revelation to ontology, does not transcend Scripture but clarifies its internal architecture. Where the historical theologian secures the fidelity of meaning, the ontological analyst secures the coherence of reality—showing that redemption is not merely possible but necessary within the moral fabric of the universe.

This study operates at the third tier. It presupposes the hermeneutic and doctrinal labours of earlier levels but moves to a dogmatic ontology—showing not only what is true, but why it must be so. The exegete hears revelation; the theologian systematises it; the ontologist discloses its structural inevitability. Thus, the argument that Christ had to die is not speculative metaphysics but the final articulation of revelation’s own inner logic—where Scripture’s moral realism becomes ontological necessity.