Across centuries of commentary, theologians have handled David’s fall with a peculiar gentleness.Catholic, Protestant, and modern devotional writers alike tend to veil the event in the language of repentance and divine mercy, as though the sincerity of David’s tears could offset the gravity of his crimes. Even within the most conscientious expository traditions—including those that pride themselves on moral accountability—this story is treated as a model of forgiveness rather than as a mirror of judgment.

Yet this interpretive softness comes at a cost. It domesticates the scandal, converting a moral outrage into a sentimental reassurance. The emphasis on repentance—however genuine—has obscured the deeper architecture of the narrative: that David was spared not because God was lenient but because God was bound. The survival of his throne was not the triumph of grace over justice but the display of a justice postponed for the sake of covenantal continuity.

In many denominational readings, including those that trace a lineage to the Reformation and its later movements, David’s story is invoked to exemplify divine mercy extended to the repentant sinner. But this is an inadequate lens. It explains the psychology of forgiveness while ignoring the ontology of divine fidelity—the fact that God’s commitment to His own word, not David’s contrition, kept the monarchy alive.

This essay therefore sets out to expose the moral and theological evasions surrounding David’s preservation. It does so not to diminish repentance but to restore proportionality to the divine narrative. Grace, properly understood, is not a sentimental pardon; it is the costly endurance of a God who refuses to contradict Himself. What follows is an attempt to read the story as it stands—without euphemism, without theological cosmetics, and without the illusion that David’s greatness lies anywhere but in the God who refused to erase him.

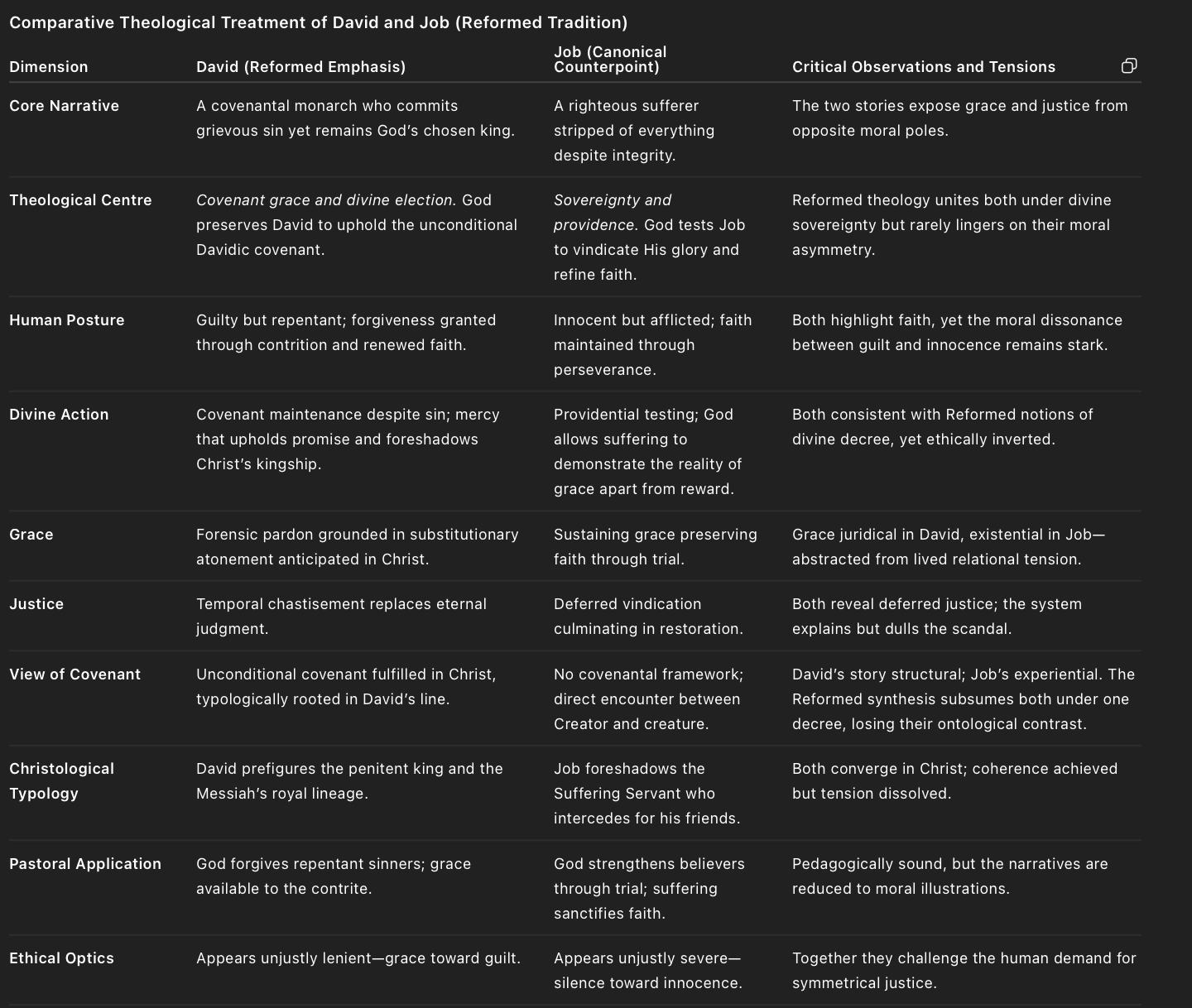

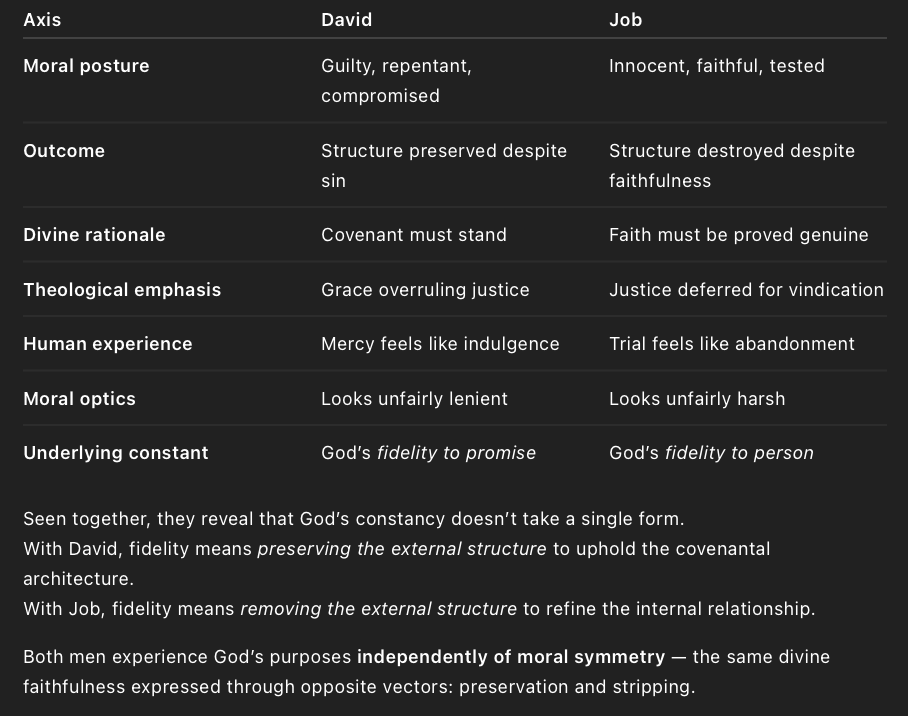

The following comparative section situates this essay within the broader theological landscape of Reformed interpretation.Reformed theology, with its robust doctrines of covenant and sovereignty, regards the stories of David and Job as complementary manifestations of divine constancy—one revealing grace through guilt, the other justice through suffering. Both figures are enlisted to illustrate the immutability of God’s will. Yet in achieving doctrinal symmetry, this system often conceals the narrative asymmetry Scripture itself preserves: the scandal that divine fidelity may appear indulgent in one case and cruel in another.

The comparison below does not reject Reformed theology but exposes the ontological core it too easily rationalises—the reality that God’s faithfulness is not a moral balancing act but a manifestation of His being. What unites the two narratives is not psychological experience or moral proportion, but the same ontological constant: divine self-consistency expressed through radically different forms of human fortune.

iii. Analytical Commentary — Ontological Reading

iii. Analytical Commentary — Ontological Reading

Read together, David and Job reveal not two gods but two dimensions of the same divine constancy. The Reformed tradition correctly sees both stories as theatres of sovereignty, yet in its quest for logical symmetry it often abstracts God’s fidelity into decree, losing its ontological weight.

In David, fidelity preserves structure—God remains true to His word despite moral collapse.In Job, fidelity preserves relationship—God remains true to His being despite human bewilderment.One is the architecture of promise; the other, the crucible of personhood.Their convergence discloses an ontological symmetry: God never ceases to be Himself.

But it also exposes a moral asymmetry: divine constancy does not manifest in ways that satisfy human fairness. Grace may appear indulgent; justice may appear cruel; yet both are expressions of the same immutable faithfulness. The difference lies not in divine temperament but in divine purpose. God’s being is consistent; His methods are not symmetrical.

Reformed theology preserves the structure of sovereignty but too often explains away the scandal that gives it texture. The true insight of these twin narratives is not that God governs all things, but that He bears the cost of doing so—upholding His word through moral ruin and His righteousness through undeserved suffering. This is the ontology of fidelity: a constancy so absolute it can inhabit contradiction without ceasing to be holy.

What follows applies this same constancy to the most unsettling of cases—the preservation of a compromised king.

There is no way to varnish what David did.He saw a woman bathing, summoned her, lay with her, and when the web of deceit threatened to unravel, he arranged her husband’s death. It was adultery sharpened by power, murder masked by statecraft, and cowardice wrapped in privilege. Yet this man, whose conscience slept while others bled, remains in Scripture’s memory not as a cautionary tale but as a hero—the “man after God’s own heart.” His psalms fill our hymns; his repentance is praised as exemplary.

That dissonance demands confrontation. How can a God of justice leave such a stain on the throne and still call the dynasty blessed? Why should Saul lose his crown for an ill-timed sacrifice while David retains his after calculated betrayal? The story offends our moral sense precisely because it should. It exposes the scandal at the centre of sacred history: a holy God who refuses to un-choose an unholy man.

The thesis of this essay is therefore simple and severe. David was spared, not because he was righteous, but because God had already bound Himself by promise. His survival is not the triumph of repentance but the endurance of divine fidelity; a covenant upheld at the cost of moral symmetry. Grace here does not comfort—it convicts.

To see the crime clearly, one must strip away the devotional haze that centuries of commentary have thrown over it. David’s sin was not a private lapse of passion; it was the exploitation of power by a sovereign who treated human life as expendable collateral.Uriah was not merely a husband wronged but a loyal soldier sacrificed to protect the king’s image. Bathsheba, summoned to the palace, possessed little real agency; consent under royal command is never free. The ensuing cover-up, deceit, and orchestrated death make the narrative read less like romance and more like indictment.

The prophet Nathan’s parable of the ewe lamb pierces the veil. In a few strokes he exposes the moral obscenity: the rich man who takes the one lamb of the poor because he can. David’s sudden self-condemnation—“the man who has done this deserves to die”—is the only moment of justice in the story, and it comes too late.

Repentance, however sincere, cannot restore Uriah’s life or Bathsheba’s dignity. The psalms of contrition reveal a conscience reborn, not a world repaired. David’s repentance restores his relation to God, but not the victims of his sin. The moral debt remains unpaid, absorbed into history by divine patience rather than human restitution.

Here the outrage deepens. Saul disobeys a ritual command and is stripped of kingship; David violates every commandment in one sordid sequence and keeps his crown. From the human standpoint it is inequity bordering on mockery. The law that should condemn him instead appears to bend around him.

David’s record leaves little room for romanticism. His moral breaches form a litany of power abused: the adultery with Bathsheba and the engineered death of her husband Uriah (2 Samuel 11 : 2 – 17); the unlawful census taken in defiance of divine command, bringing judgment upon Israel (2 Samuel 24 : 1 – 15); and, at the very close of his life, the extrajudicial sanctions he delivered to his son Solomon — ordering the executions of Joab, who had fled to the altar, and Shimei, despite previous oaths of clemency (1 Kings 2 : 1 – 9, 28 – 46). Even his leniency toward Amnon after the rape of Tamar (2 Samuel 13 : 1 – 21) and his fractured dealings with Absalom (2 Samuel 14 – 18) show a ruler increasingly ruled by circumstance. The biblical record does not disguise these acts; it preserves them as witness that the covenant endured not because the king was just, but because God would not forswear His own word.

To later readers this looks like the theology of privilege—divine monarchy mirroring earthly impunity. Yet the narrative itself offers a different explanation, one that turns favouritism on its head. David is not spared because he is special; he is spared because God’s word is. The covenant spoken in 2 Samuel 7 — “Your house and your kingdom shall be established for ever before Me” — cannot be revoked without God ceasing to be truthful. The promise, once uttered, becomes the trap of divine fidelity.

Thus the asymmetry is not indulgence but consistency: God upholding His own integrity even when it means carrying a compromised vessel. The preservation of the throne is the price of a promise that God refuses to break. What looks like mercy to David is, in reality, the burden of divine constancy — justice postponed until it can be transfigured in another Son of David who alone will bear it rightly.

The pattern of indulgence and divine patience extends beyond David into Solomon, his heir and instrument of covenant continuity. Solomon inherits not only the throne but the unresolved moral asymmetry of his father’s reign. The same fidelity that preserved David’s kingdom now preserves Solomon’s, even as he multiplies the very transgressions Israel’s law forbids.

1. Political Assassinations and Vengeance (1 Kings 2:5–46) In David’s final commands, the dying king enjoins Solomon to execute Joab and Shimei—extra-judicial acts cloaked as justice. Solomon’s compliance marks the monarchy’s descent from moral restoration to realpolitik, turning paternal repentance into dynastic consolidation.

2. Diplomatic Idolatry and Syncretism (1 Kings 3:1; 11:1–8) Solomon marries Pharaoh’s daughter, builds shrines for foreign deities, and accommodates the cults of his many wives. Wisdom coexists with apostasy: revelation entwined with expediency.

3. Economic Exploitation and Conscription (1 Kings 5:13–18; 12:4) His monumental building projects rely on forced labour, echoing Egypt’s oppression—the very bondage from which Israel was delivered. Covenant history folds back upon itself in tragic symmetry.

The narrative logic remains identical: divine fidelity persists through moral erosion. The kingdom stands, not because the king is righteous, but because the word once spoken cannot be withdrawn. Solomon’s splendour and decline mirror David’s sin and survival—two halves of the same covenantal contradiction.

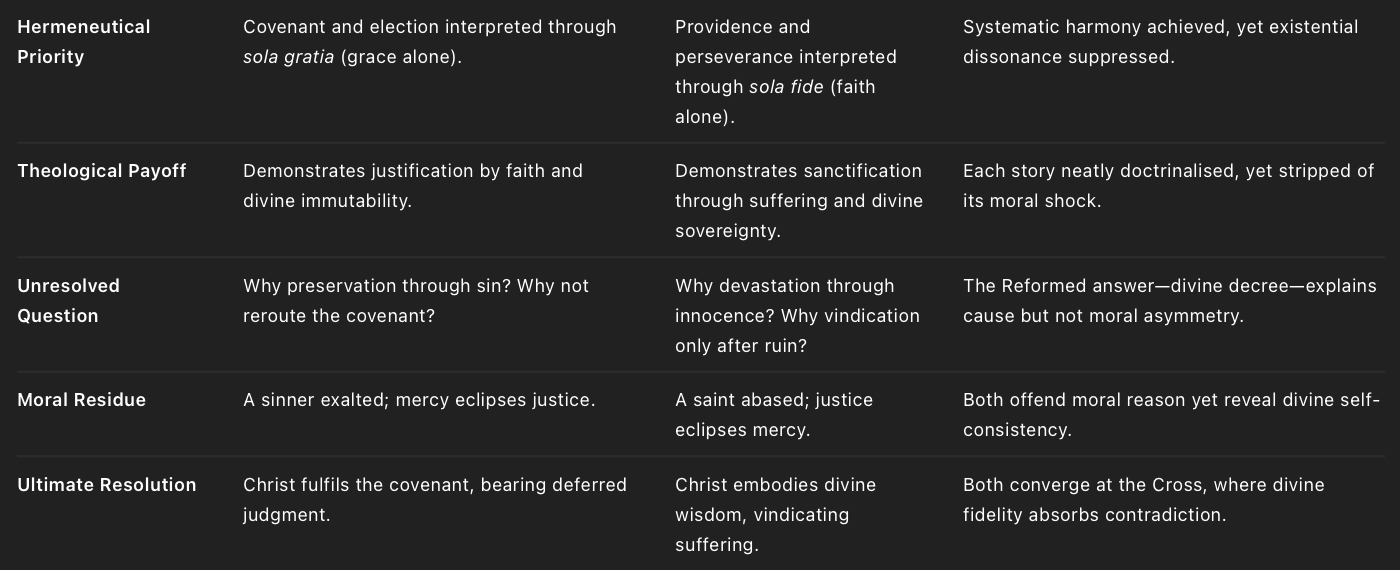

The pattern of divine treatment across Scripture reveals a striking asymmetry. When moral collapse occurs inside the covenantal structure, judgment is delayed; when it occurs outside, it is immediate. The difference is not divine partiality but divine architecture: once God has bound Himself to a public covenant, His own word stands between offender and retribution. Fidelity itself becomes the restraining force.

David’s psalms overflow with gratitude for mercy received, yet his praise remains experiential rather than architectural. He feels the tenderness of forgiveness without discerning the structure that made forgiveness possible. What he names as compassion is in fact divine self-restraint: God’s fidelity absorbing guilt to preserve His own word. David’s doxology is true in tone but incomplete in comprehension—the gratitude of a man spared by love, unaware that the mercy he celebrates already presses upon the boundaries of justice. His songs give voice to grace as emotion; the covenant reveals it as ontological endurance.

Each of these men commits acts that would have destroyed an ordinary life.

Moses kills an Egyptian (Exod 2:11–15), an impulsive act of vengeance that anticipates his later failure at Meribah (Num 20:7–12). Yet he remains the mediator through whom the law and the covenant are given. His discipline is severe—barred from Canaan—but his vocation remains intact. He dies under judgment yet in intimacy, buried by the God he offended (Deut 34).

David commits adultery and murder (2 Sam 11–12) but retains the throne. His personal disgrace becomes the means through which divine fidelity is displayed to history.

Solomon, though gifted with wisdom, descends into syncretism and exploitation (1 Kgs 11). His reign endures, and judgment waits until after his death.

In all three, divine judgment is deferred within relationship. God disciplines but does not displace; He bears the contradiction Himself so that the covenant’s structure remains unbroken. Their preservation is vocational, not moral—the covenant must outlast its carriers.

Those standing outside the covenant encounter unmediated justice.

Pharaoh’s defiance ends in ruin (Exod 14).

Saul’s impatience costs him the kingdom (1 Sam 15).

Nebuchadnezzar’s pride collapses into humiliation (Dan 4–5). No structural promise stands between them and divine response. Once their function is fulfilled, judgment falls without delay.

The closer one stands to the covenant’s centre, the slower the judgment falls—not because God is indulgent, but because His fidelity to His own word restrains His hand.

Covenantal incumbency thus creates insulation without exoneration. The nearer the role to the architecture of redemption, the longer God endures its failure for the sake of continuity. Moses is disciplined within intimacy; David and Solomon are preserved within disgrace; Pharaoh, Saul, and Nebuchadnezzar are exposed without buffer.

From Job’s blameless endurance at one pole to David’s and Solomon’s preserved guilt at the other—and from Moses’s disciplined mediation to Pharaoh’s immediate ruin—Scripture traces a spectrum of divine response. Justice is never absent but manifests differently according to proximity to covenantal purpose. The paradox is stark: innocence undone, guilt sustained, holiness compromised yet not revoked. The moral imbalance that emerges here will find its resolution only where covenant and fairness finally meet—in the self-bearing fidelity of God Himself.

The turning point of the story lies not in David’s character but in God’s speech.Before the Bathsheba affair, God had sworn an oath through Nathan: “I will raise up your offspring after you… and I will establish the throne of his kingdom for ever.” With those words, divinity entered into a form of self-obligation. The promise was unconditional; the architecture of the kingdom became a mirror of God’s own constancy.

When David fell, God faced a paradox that no human court could contain. To revoke the covenant would be to contradict His own nature; to uphold it would seem to condone evil. In that impossible space, grace becomes the mechanism of divine self-consistency. God does not approve the man; He preserves the word. The same faithfulness that will one day bring the Messiah into the world forces Him, for now, to sustain a throne occupied by a murderer.

This is the scandal at the heart of covenant theology: the Holy One binds Himself to the unholy and refuses to tear the bond apart. The cost of that fidelity will not vanish; it will accumulate across generations until it is finally paid in blood by the only Son who can bear both justice and promise without contradiction.

David’s preservation, then, is not reward but burden. The sinner becomes the conduit of salvation, his disgrace transformed into a structural necessity. Bathsheba, too, is drawn into this grim irony. The very union that embodied betrayal becomes the channel through which Solomon is born and the covenantal line continues. The scandal is not concealed; it is woven into the fabric of redemption so that no future generation can mistake the dynasty for a monument to human virtue.

Had God chosen another of David’s wives, the line might have looked respectable, the story forgettable. Instead He chooses the one name that cannot be mentioned without recalling sin. In doing so He declares that His purposes will advance through human ruin, not by pretending it never happened. Every genealogy that traces Christ’s descent through “the wife of Uriah” repeats the confession: grace is sovereign, merit is irrelevant.

The Ark of the covenant once symbolised divine presence resting among a holy people; now the covenant itself rests on a broken man. What began as the privilege of election has become the humiliation of being used. David is not celebrated; he is conscripted. His throne endures because God refuses to abandon His own design, not because the occupant deserves the honour of maintaining it.

To uphold a promise in the face of betrayal is to suffer for one’s own truthfulness. Every time God preserves the unworthy, He bears the moral weight that justice would otherwise demand from them. The preservation of David’s line is therefore an act of divine self-wounding: God absorbing into His own reputation the shame that rightfully belongs to another.

History will remember the “house of David,” but heaven records the cost in the patience of God. The covenant’s endurance tarnishes His name before it vindicates it. Israel’s prophets will spend centuries lamenting a kingdom corrupted from its root, yet through that corruption the messianic promise keeps breathing. Grace here is not leniency; it is endurance. It is the willingness of God to be misunderstood as partial so that His faithfulness may one day be seen as perfect.

When the promise finally reaches fulfilment, the scandal that began on a rooftop will converge on another: a cross. There, divine fidelity meets its own consequence, and the justice postponed in David’s day is executed in full. The mercy that once looked like favouritism is revealed as the costly consistency of a God who keeps His word even when it tears His own heart apart.

Even David’s psalms, though fervent in thanksgiving, reveal an incomplete gratitude. They magnify the mercy that rescued him, yet they do not apprehend the deeper wonder—that God upheld His own word in spite of David’s collapse. The praise rises from personal deliverance, not from awe that divine fidelity remained unbroken amid human failure. In his psalms, grace is experienced as pardon, not yet recognised as God’s unwavering constancy to His covenant. His hymns thank the God who forgave him, but not the God who remained faithful to Himself while doing so.

The preservation of David’s line is not the annulment of justice but its relocation. The sword never departs from his house; every generation bears a splinter of his guilt. Yet the covenant persists until the day justice and promise meet in the same body. The paradox of redemption is that grace does not cancel justice—it fulfils it in another key.

When the genealogy of Matthew names “the wife of Uriah,” it refuses to let the scandal die. Tamar, Rahab, Ruth, Bathsheba—each stands as a witness that God does not curate history to protect His reputation. He writes salvation through the compromised and the outcast so that redemption can be traced, line by line, through human ruin. What began as the embarrassment of divine patience becomes the proof of divine sovereignty: a holiness that can inhabit contamination without becoming contaminated.

Thus the “grace that overrules” is not sentimental. It is justice displaced forward, held in suspension until it can be borne by One whose righteousness is sufficient for both sinner and system. In Christ, the covenant’s deferred sentence is served in full. The line of David is simultaneously condemned and redeemed; the throne that once sheltered guilt becomes the emblem of a kingdom founded on unbreakable mercy.

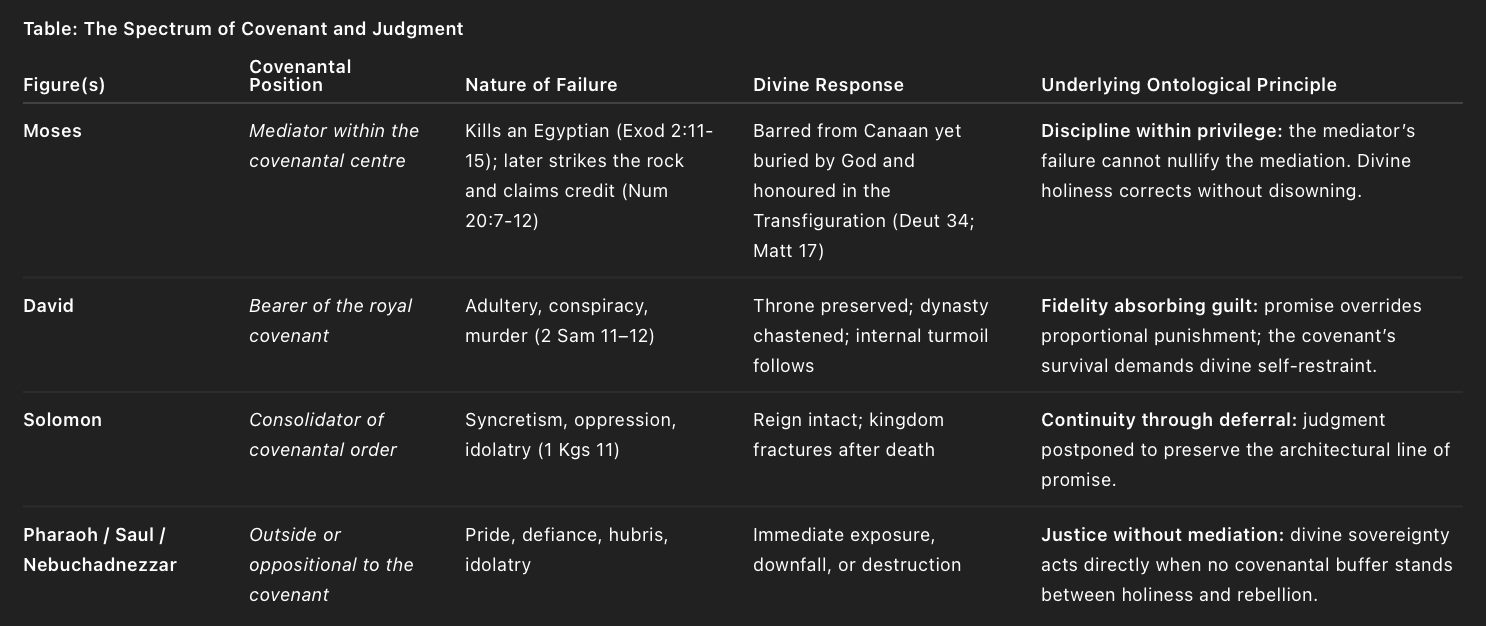

If David’s story is the scandal of guilt preserved, Job’s is the scandal of innocence destroyed. One man keeps the kingdom despite sin; the other loses everything despite righteousness. Yet both belong to the same spectrum already traced in Scripture: from Moses’s disciplined mediation, through David’s and Solomon’s deferred judgment, to Job’s dismantled integrity on one end and Pharaoh’s, Saul’s, and Nebuchadnezzar’s exposure on the other. Each station on that spectrum reveals a different aspect of divine constancy—discipline within covenant, preservation within failure, dismantling within faith, and destruction outside grace.

In David, faithfulness takes the form of architectural preservation; in Job, it takes the form of relational stripping. Grace works outward in the king and inward in the sufferer. To David, divine constancy feels indulgent; to Job, it feels cruel. Yet each demonstrates the same ontological symmetry: God remaining true to Himself even when fairness collapses in human sight. The nearer one stands to the covenant’s centre, the longer the patience of God endures; the farther one stands, the swifter His holiness acts.

Together they disclose the mystery that justice and mercy are not alternate moods of God but concurrent dimensions of His being. One preserves the structure of promise; the other purifies the heart of trust. David’s spared guilt and Job’s tested innocence are opposite faces of the same fidelity—one structural, one existential, both absolute.

Divine fidelity extends beyond the preservation of covenants and the testing of saints; it shapes individuals for appointed purposes. Scripture consistently depicts humanity not as static recipients of grace but as material under formation. Isaiah’s potter (Isa 64:8), Peter’s living stones (1 Pet 2:5), and Paul’s image of the body “fitly framed together” (Eph 4:16) all describe a God who works as craftsman rather than curator. The blows of circumstance, the abrasion of loss, and the heat of trial are His chisels and furnaces.

Malachi speaks of the Lord who “sits as a refiner and purifier of silver,” while Zechariah hears God promise, “I will bring the third part through the fire… they shall call on my name, and I will answer them.” These images are not punitive but teleological: fire and hammer exist to prepare, not to destroy. In the quarry of time each life is cut to measure, its edges honed until it fits within a design known only to the Architect. What feels like arbitrary suffering is the discipline of precision—the shaping of material for a structure yet unseen.

Thus fidelity to purpose is the quiet corollary of fidelity to promise and to person. God remains consistent not only in what He has spoken and whom He has loved, but also in what He is making. The same constancy that sustained David’s line and vindicated Job’s endurance continues to refine all who are drawn into His workmanship, that they might one day stand—fitted, tempered, and enduring—within the architecture of His final dwelling.

David’s name should not be spoken without shame. He violated covenant, corrupted power, and cloaked murder in prayer. His repentance may have been genuine, but repentance does not erase consequence. The glory of his story lies not in his recovery but in God’s refusal to revoke His word. The throne endured because God’s integrity could not be broken, not because the king was worth keeping.

Through David’s disgrace and Job’s affliction, the same revelation emerges: God’s faithfulness does not depend on human success or failure; it depends on His own nature. Sometimes that faithfulness preserves a dynasty; sometimes it dismantles a life. In both cases it moves history toward a redemption no mortal deserves.

Yet divine fidelity is not exhausted by history’s great figures. The same constancy that sustained David’s line and vindicated Job’s endurance continues to shape ordinary lives with the precision of an unseen craftsman. Scripture’s images of the potter’s wheel and the refiner’s fire reveal a purpose that works through adversity as surely as through promise. Each soul is a stone cut, chiselled, and tempered for its appointed place in a structure still under construction. The heat of trial and the abrasion of loss are not divine neglect but divine workmanship—the slow perfection of a design we rarely glimpse. Fidelity to purpose means that no pain is wasted, no discipline arbitrary, no obscurity meaningless.

Grace, then, is not divine softness—it is divine endurance. It bears the contradiction between justice and promise until the contradiction can die in Christ. The scandal remains the frame through which fidelity is seen. From every human vantage, David simply got lucky—he stood inside a covenant that could not break. Yet what we call luck, Scripture calls fidelity: the strange mercy of a God who keeps His word even when it exposes His holiness to scandal, and who still refines His people with the same relentless care until they fit the architecture of His eternal design.

The shame is David’s; the constancy is God’s; and the story endures because truth Himself refused to break His own word.

In the end there is no moral arithmetic that satisfies; there is only endurance in the trust that God’s purposes remain good, even when they appear grotesquely uneven.