This section addresses the collapse of secular moral reasoning and the recovery of moral coherence through what this framework calls the axiological–deontic–modal taxonomy. Modern ethics retains the vocabulary of value, duty, and freedom, but detaches these from ontological grounding—reducing moral life to abstraction, consensus, or utility. In contrast, the biblical model restores value as what God deems good, obligation as what God requires, and possibility as what God makes necessary or permissible—each embedded in a structure of revealed moral order. The aim is not to construct morality, but to recover the intelligibility and coherence of moral life within the covenantal reality of God’s created order.

Morality is not a matter of personal conviction, social consensus, or behavioral compliance. It is the visible manifestation of a deeper orientation: the soul's response to the presence of truth. Before it is about action, morality is about alignment—a posture toward divine reality that either yields or resists. In this framework, moral evaluation is not the classification of external deeds, but the discernment of relational fidelity or suppression.

Secular models fail at this root. The therapeutic model reduces morality to psychological wellness. The legal model reduces it to rule violation. The evolutionary model reduces it to cooperative advantage. Each begins not with divine order, but with the human subject as its own point of reference. As such, they may describe behavior, but they cannot diagnose rebellion.

The biblical framework begins elsewhere. It sees morality not as self-referential or utilitarian, but as covenantal participation in the moral order embedded in creation—an order that reflects the character of God. Moral truth is not abstract, but ontologically real, and always relationally disclosed.

Thus, moral taxonomy is not a system for labeling sins, but a grammar of ontological rupture. It distinguishes between failures of value (iniquity), failures of volition (transgression), and failures of action or inaction (sin)—each corresponding to a structural breakdown in the soul’s alignment to truth. These categories are not arbitrary; they are discerned by their proximity to the moment of divine confrontation and the soul’s response.

To name these rightly is to call the soul back to reality.

This section is titled Moral Taxonomy not as a gesture toward systematization for its own sake, but to recover the act of right naming and right classification of moral deviation within an ontological and relational frame. In contrast to therapeutic models that reduce wrongdoing to emotional dysfunction, or legalistic models that quantify sin by behavioral codes, this taxonomy identifies moral failure according to its relational root, its ontological distortion, and its moral posture.

The term taxonomy signals that moral categories are not interchangeable labels but structurally differentiated realities. Just as biology distinguishes between genus and species based on ontological traits, this framework distinguishes between iniquity (axiological disorder), transgression (volitional breach of relationship), and sin (modal execution of disordered action). Each category reflects not merely what was done, but where the failure lies within the person’s alignment to God’s order.

To classify morally is to diagnose truthfully. This taxonomy thus serves both an epistemic and restorative function—identifying where relational reality has been suppressed or distorted, and how that distortion maps back to the moral architecture embedded in creation and conscience. This taxonomy does not restrict itself to rare or extreme actions. All moral acts reveal the moral agent's noetic posture (the volitional and affective internal orientation of the soul toward revealed or known moral truth)—none are neutral—but not all acts carry equal epideictic weight. Some signal subtle trajectory; others serve as decisive moments of moral confrontation. The most theologically significant acts—those most sharply named by this taxonomy—are those that arise when the will is confronted with truth and chooses either suppression or fidelity. These are not merely behaviors; they are epideictic disclosures—relational moments in which the soul's moral alignment is summoned into the light. In this sense, taxonomy is not merely classification after the fact, but the ontological naming of volitional response to divine summons in time.

Classical virtue ethics and biblical covenant alike assumed that duty (deon) flowed organically from purpose (telos). Morality was participatory: the good life meant aligning with the divinely ordered reality that defined one’s nature and end. For Aristotle, habituated virtue fulfilled a natural telos; for Scripture, obedience expressed relational fidelity to the Creator whose character the law reveals (“Be ye holy, for I am holy”). Value, obligation, and purpose therefore formed a single ontological braid.

Late-medieval voluntarism ruptured that braid. William of Ockham located moral authority in sheer divine fiat, severing command from character and leaving duty potentially arbitrary. Early modern ethics secularized the split: Kant grounded law in autonomous reason, banning telos from moral calculus, while utilitarianism flipped the scheme—pursuing outcomes without intrinsic duty. What began as a theological bid to protect divine freedom ended in a landscape where obligation is hollow and purpose collapses into sentiment or power.

Thomas Aquinas had called Natural Law “participation in the Eternal Law,” harmonizing reason with revelation. Enlightenment thought kept the legal vocabulary but dropped the source, recasting Natural Law as a freestanding rational consensus. Thus justice became procedural (Kantian formalism, Rawlsian fairness), and praxis was secularized—measured by social utility, biological inclination, or psychological wellness. Rights-language persisted, yet its ontological anchor was cut; moral discourse now floats, autonomous and abstract.

Bridge to the next section These three moves—voluntarist fiat, procedural rationalism, and the secularized Natural Law project—emptied modern ethics of its ontological core. What follows examines the fallout of that hollowing and the path to recovery.

As §§ I.B–I.C demonstrated, severing duty from purpose, exalting will above being, and detaching natural law from divine revelation evacuated the moral order of its ontological core. What survives is only the language of value, duty, freedom, and right—now unmoored from the covenantal ground that once gave it coherence.

Section II therefore shifts from genealogy to diagnosis, mapping the philosophical fragmentation that this hollowing has unleashed.

he collapse of moral coherence in the modern era is not merely a clash of values or cultures. It is the fallout of the ruptures traced above: duty severed from purpose, natural law estranged from divine law, and moral ontology removed as the ground of ethical life. Ethics has become a patchwork of deontological formalism, utilitarian calculus, and emotive expressivism, each attempting to govern moral life without reference to divine design, ontological reality, or teleological destiny.

This section names and diagnoses the fourfold fragmentation of modern moral thought:

Axiology, what is “good,” has been severed from any fixed moral telos. Classical and biblical frameworks understood value as the expression of divine character or intrinsic alignment with one's created nature. But modern theories treat values as either expressions of will (Nietzsche), emotive responses (Ayer, Stevenson), or self-generated meaning (Taylor). The self, rather than God or nature, becomes the final arbiter. Axiology is no longer discovered or revealed, but performed; no longer discovered, but invented. What was once the recognition of divine worth is now reduced to sentiment, taste, or power.

Kant’s categorical imperative attempted to ground obligation in rational universality. But in doing so, it divorced duty from relational or ontological content. One must act out of duty—but duty to what? The moral law becomes a formal procedure, not a lived allegiance. Subsequent theorists such as Rawls abstracted justice even further, imagining hypothetical starting points or neutral procedural conditions. But the result is the same: a moral architecture without moral substance. These systems provide mechanisms, not meaning. Obligation becomes negotiable, impersonal, and ultimately vulnerable to ideological manipulation.

Utilitarian ethics inverted the Kantian framework—preserving telos, but sacrificing obligation. In this view, the moral worth of an act is measured not by its alignment with the good, but by its effectiveness in achieving desirable outcomes (pleasure, preference satisfaction, social utility). Right and wrong are judged by results, not by righteousness. As Foucault noted, such frameworks often disguise systems of control under the language of care. Ethics becomes a tool for shaping populations, not sanctifying persons. In the absence of a fixed moral referent, ends are manufactured by regimes of consensus, not revealed by the order of being/kinds.

Where earlier systems at least debated what should be done, the postmodern turn has collapsed the question of “ought” into the realm of “can.” What is technologically feasible or psychologically tolerable becomes de facto permissible. Authenticity, self-expression, and subjective coherence are elevated to moral goods, while any claim to objective or external moral order is treated as oppressive. Freedom is no longer defined as the capacity to live in alignment with truth, but as the ability to dissolve all constraint—even ontological. Modality becomes untethered from obligation—possibility is mistaken for permission, and permission mistaken for truth.

These divergent frameworks—subjectivism, proceduralism, utilitarianism, and postmodern relativism—converge in their rejection of ontological grounding. Each preserves fragments of the moral structure: value, duty, telos, or freedom—but none can reunite them. The result is not ethical pluralism, but ontological incoherence: rules without a rule-giver, imperatives without authority, values without truth, and freedom without form.

This model does not attempt to construct morality anew. It seeks rather to recover its intelligibility through realignment with moral reality as revealed by God. Value must once again flow from divine character. Obligation must arise from participation in divine order. Possibility must be governed by what God enables or forbids. The moral crisis, at root, is a crisis of being: a rejection of moral ontology in favor of procedural substitutes. What follows exposes the full scope of the loss before turning to its remedy.

Where modern ethical frameworks disintegrate under the weight of autonomy, abstraction, and utilitarianism, the biblical model offers not an alternative theory, but a relational and ontological restoration. Morality is not invented, constructed, or deduced; it is relationally revealed, ontologically grounded, and covenantally encountered—rooted in God’s character and made intelligible through moral participation.

Yet this restored moral order is not only external or conceptual. It is encountered and experienced within the moral agent, in what we may call the phenomenological space: the interior arena where duty presses, value confronts, and possibility is weighed. This space is not merely psychological—it is morally structured. It is where the soul becomes conscious of its confrontation with truth, and where the Deontic–Modal (DM) unit is registered, received, resisted, or obeyed.

The DM unit represents the divine imprint of moral structure within the human soul—an ontologically fixed framework that discerns obligation (deontic) and possibility or necessity (modal), always present by virtue of image-bearing and design (Jer. 31:33; Heb. 8:10; Ezek. 36:26–27; Rom. 2:14–15). This DM unit is the internal moral structure where divine truth is either received or resisted (suppressed). The rubrics of the DM unit are inspired by and reflect the Creator’s character and axiology. It does not evolve—it is either yielded to or suppressed. This internal moral unit is confronted, and in that confrontation, the noetic posture is revealed: the volitional and affective disposition of the soul toward revealed or known moral truth.

The law “written on the heart” (Jer 31:33; Rom 2:14-15) surfaces in human experience along a full interior arc—knowing → valuing → willing → acting. Each stage can break down, and together they span every way a moral agent can resist or comply with truth: (1) Noesis names the cognitive grasp of what God requires; error here is ignorance or self-deception. (2) Posture captures the affective valuation of that known requirement; failure is dislike, dread, or indifference toward the good. (3) Disposition registers the settled inclination that follows valuation—either humble assent or proud antagonism; here the will begins to tilt. (4) Volition is the executive choice that translates inclination into concrete intention and action. Because every moral response must first be understood, then appraised, then embraced or resisted, and finally chosen, these four loci exhaust the places where alignment can break—nothing can be omitted without leaving a gap, and nothing can be added without redundancy.

The Deontic–Modal unit names the internal moral architecture by which God confronts the soul with responsibility. It includes:

These are not abstract ethical categories—they are covenantal disclosures, grounded in God’s authority and inscribed upon the conscience. They operate within all humans, though often suppressed, and are brought into clarity and power through regeneration. They do not override the will, but summon it. They are not culturally variable, but morally invariant, even when misperceived or resisted.

In a pre-regenerated individual, the DM unit is acknowledged partially; its claims are submitted to in some areas and suppressed in others, according to the moral agent’s volitional (noetic) posture. In a spiritually regenerated individual, there is an increasing surrender to its claims—a graduated process, manifest as integrity maintained across circumstances, animated by relational fidelity and enabled by grace.

The phenomenological space is thus where the soul stands before God—internally confronted, morally summoned, and enabled to respond. Moral realignment begins not with better comprehension, but with submission within this space to the One who is good, commands good, and makes good possible.

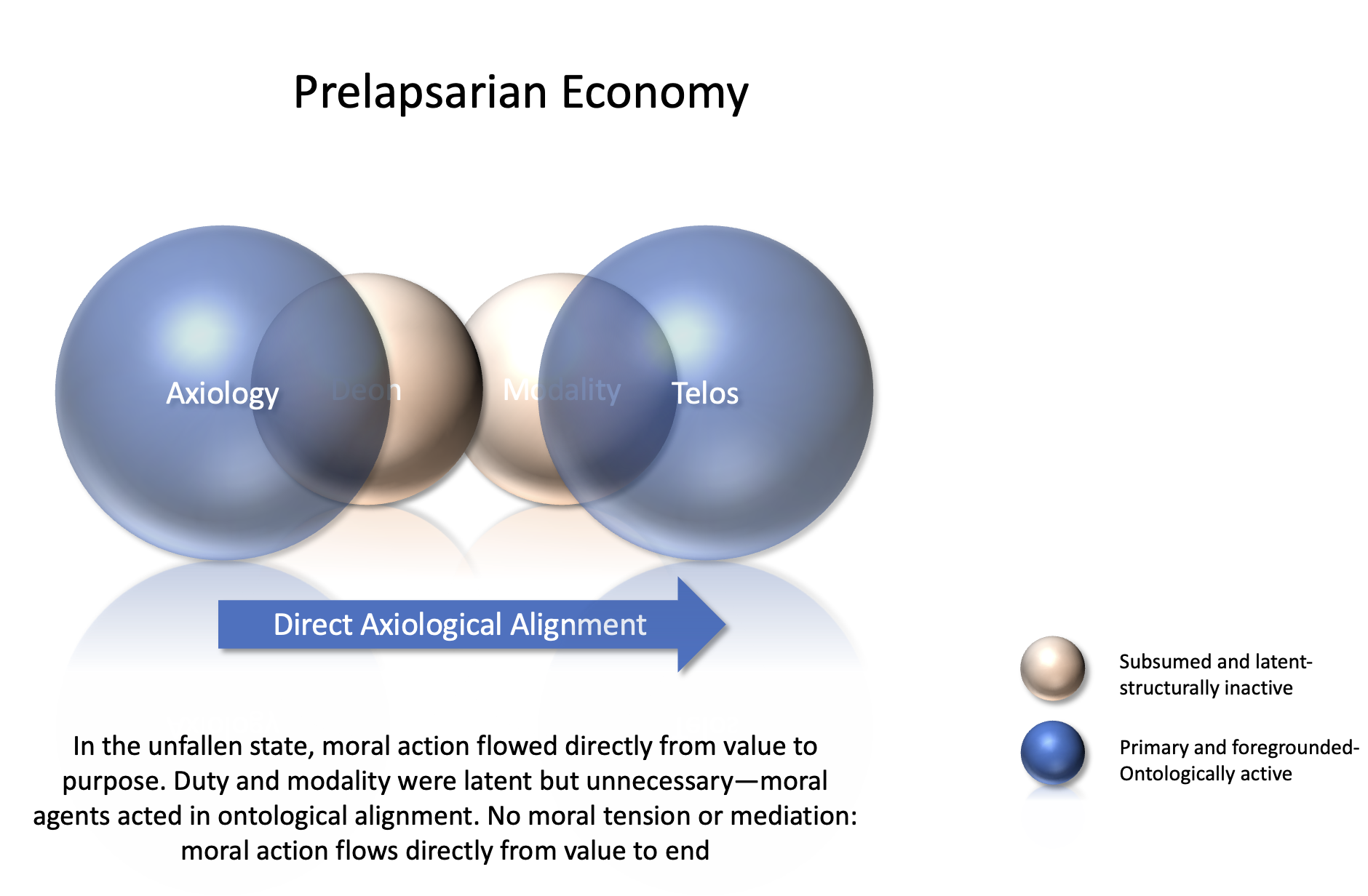

The critical difference between the prelapsarian and postlapsarian moral economy: prior to the Fall, the soul was ordered toward the good: telos was both known and desired, and duty flowed effortlessly from a heart already aligned. The DM structure was not merely present—it was joyfully operative and fully in harmony with divine axiology and will ('...thy will be done on Earth as it is in Heaven...' Matt 6:10)- to the extent that its presence was even unregistered. Moral ontology was neither obscure nor resisted; the phenomenological space was coherent, unfractured, and covenantally responsive.

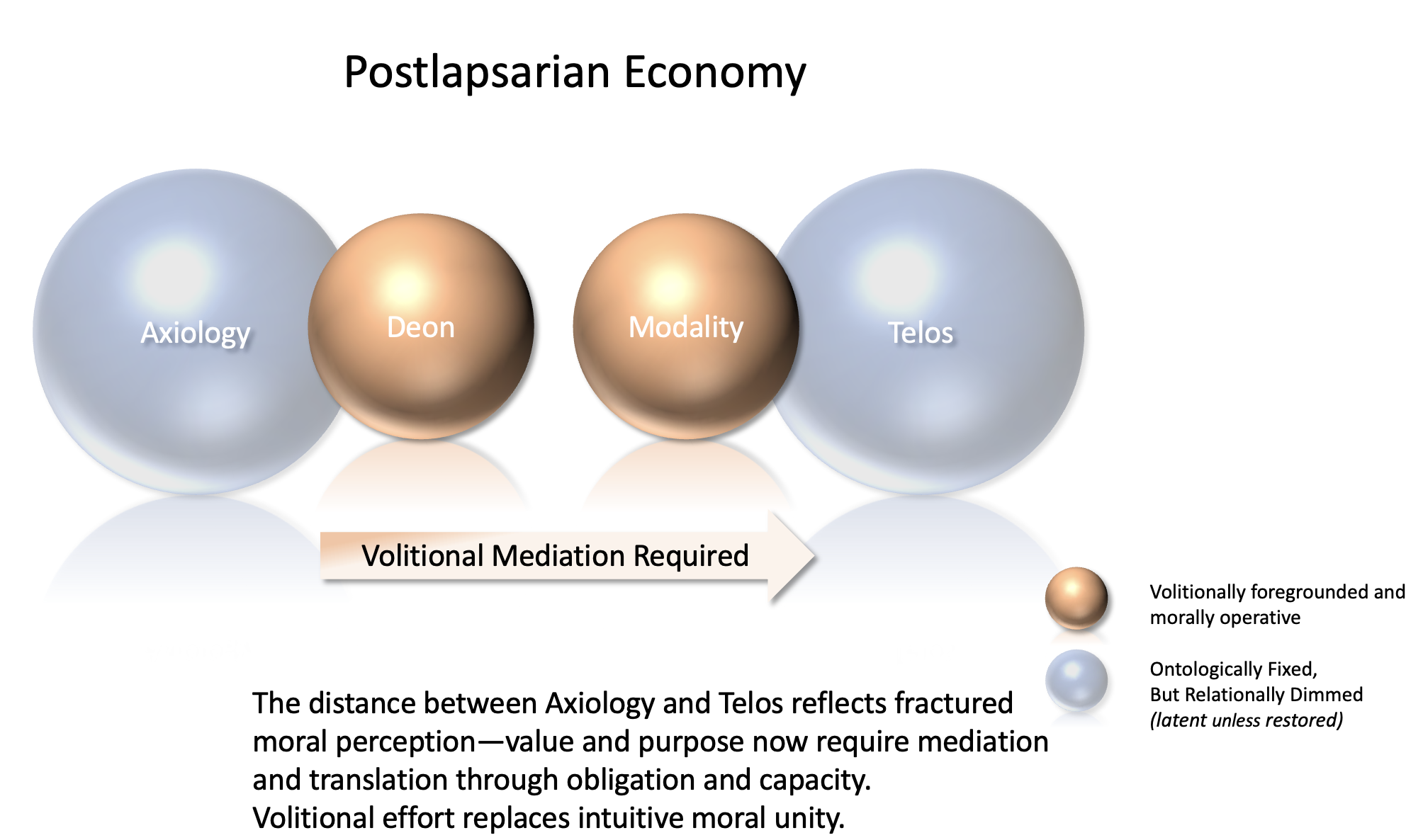

But after the Fall, the will became disordered. Telos was no longer desired with clarity, and duty no longer flowed from delight. The DM structure remained structurally intact—its moral logic was not erased—but its reception became conflicted, resisted, or ignored. In this fractured condition, the structure persists functionally, volitionally suppressed to varying degrees, no longer relationally foregrounded. The soul still perceives glimpses of value and duty, but often suppresses or sidelines them (cf. Romans 1:18). The conscience continues to operate, but its signals are misinterpreted, seared, or confined to certain domains.

It is in this context that God seeks to summon to realignment through deontic confrontation—not because duty is ontologically prior to purpose, but because the soul must now be summoned before it can comprehend. In the postlapsarian condition, deon becomes the first structure re-encountered, not by design but by necessity: conscience is pierced by obligation before desire is reawakened. Duty leads, not to displace telos, but to recover it through submission.

This inversion is not a reversal of divine order, but a gracious concession to moral fragmentation. God meets the soul where it has collapsed—in conscience (the noetic disposition in the phenomenological space)—and invites it back into relational coherence. The DM unit, then, is not only a structural imprint of God's moral architecture, but a covenantal pathway of recovery. It names both what remains in the soul and how the soul is summoned back to fidelity. Its suppressed presence explains moral discomfort; its partial operation explains selective moralism; and its awakened function marks the beginning of covenantal moral regeneration.

This recovery of telos through deontic summons presupposes that goodness itself remains fixed—anchored not in human intuition but in divine nature. Axiology, then, is not redefined post-Fall; it is merely re-encountered through mediated obedience.

Axiology—what is good or the values of the Kingdom—is not a product of consensus or cultural intuition. It is the expression of God's prerogative to define what is worthy, beautiful, and true. God alone defines what is worthy, beautiful, and true—not by fiat, but because these qualities flow from His being. The creature may respond, but never originate. Human beings are structured to recognize and respond to value, but not to generate it.

Axiology precedes and inspires deontology. What God deems good forms the basis for what He commands; what He forbids flows from what violates His nature. This is why the law is not an arbitrary code, but an ontological mirror of divine moral reality. The good is not invented, but revealed—and it is embodied supremely in His Son.

Divine value does not hover above creation as a detached ideal; it instantiates itself by shaping each ontological kind toward a fitting end. Because every creaturely telos is a concrete expression of that intrinsic worth, duty is simply the moral agent’s obligated alignment with value-in-act—the “ought” generated by value embodied in form. In short, axiological gravity exerts deontic force: what is supremely good necessarily calls forth what ought to be done.

In this restored moral framework, value, duty, and possibility are held together in divine coherence:

This trifold structure resists legalism (duty without love), antinomianism (freedom without duty), and relativism (value without truth). It reestablishes freedom as fidelity and choice as covenantal response. In this context, the moral life is not a burden, but the unfolding of restored reality. Choice becomes covenantal response, not arbitrary preference.

This structure is not merely conceptual—it is embodied. Scripture affirms that the moral law is written on the heart (Jer. 31:33; Rom. 2:15). The deontic–modal unit is experientially active within conscience, even prior to full covenantal awareness. It bears witness, convicts, and interprets reality morally—even when suppressed, it persists—often manifesting as unease, conflict, or crisis within the self. This unrest is not merely psychological—it is the moral aftershock of ontological dissonance.

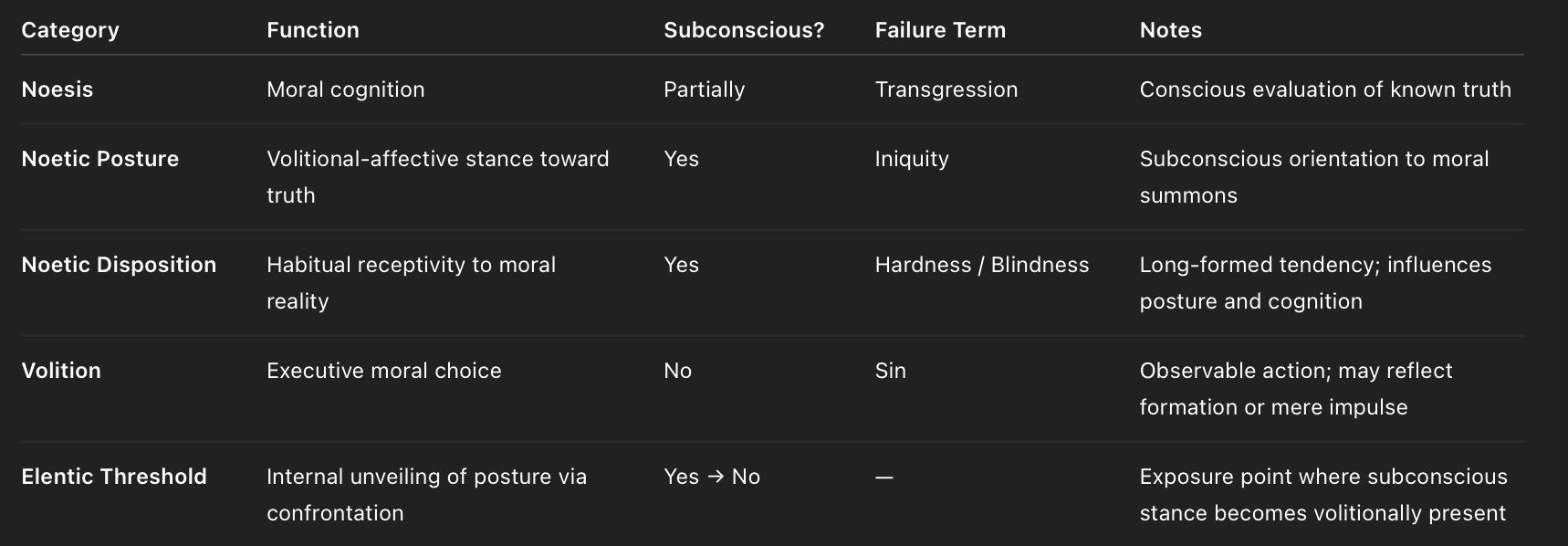

This internal witness locates the moral struggle in the phenomenological space: where duty confronts desire, where truth presses upon resistance, and where grace invites alignment. Within this morally structured interior arena—where the soul is brought into relation with revealed truth—four interrelated dynamics must be distinguished for conceptual and diagnostic clarity: noesis, noetic posture, noetic disposition, and volition.

Noesis refers to the act of moral cognition: the conscious apprehension, evaluation, and weighing of revealed or known moral truth. It occurs when value is perceived and judged in light of conscience. Deliberate moral failureat this level—whether by omission or distortion—is properly termed transgression.

Noetic posture refers to the subconscious volitional-affective orientation with which the soul receives or resists moral truth. It is not the act of reasoning, but the underlying stance—whether humble, evasive, indifferent, or eager. It governs the receptivity of the conscience even before conscious deliberation. Scripture calls this deep moral orientation iniquity.

Noetic disposition names the broader, habitual subconscious configuration of the soul’s moral receptivity. It reflects a cultivated tendency over time—formed through repeated responses to truth. It frames and shapes both noesis and posture, rendering the soul either tender or hardened toward reality. This explains how persons may be morally blind long before a specific act of sin.

Volition denotes the executive act of the will: the conscious choice to obey, delay, suppress, or simulate. It is the praxeological manifestation of internal alignment or misalignment and becomes visible in conduct. Reflexive or impulsive moral failure here—absent volitional resistance—is properly termed sin.

These four components form the diagnostic backbone of the moral agent. But to account for the moment of exposure, one more interface is essential:

Elentic exposure names the moment—typically following epideictic confrontation—when the subconscious noetic posture is brought into conscious awareness. It is not a new cognition, but an internal unveiling of the soul’s volitional stance in light of divine truth. At this elentic threshold, the will is arrested and summoned to respond: either through surrender or suppression. The soul becomes ontologically exposed to itself. What had been latent, masked by ambiguity or autonomy, is now rendered undeniable.

It is critical to distinguish these two modes of moral revelation:

Epideictic confrontation is external—a divinely initiated disclosure of reality, typically through law, gospel, conscience, or testimony.

Elentic unveiling is internal—the soul’s self-disclosure in response to that confrontation.

The former reveals divine order; the latter unveils volitional posture in response to it.

Together, they form the double movement of divine moral summons: truth made plain, and the heart laid bare.

Summary table below.

Case studies in epideictic confrontation and elentic unveiling are presented in the

Appendices

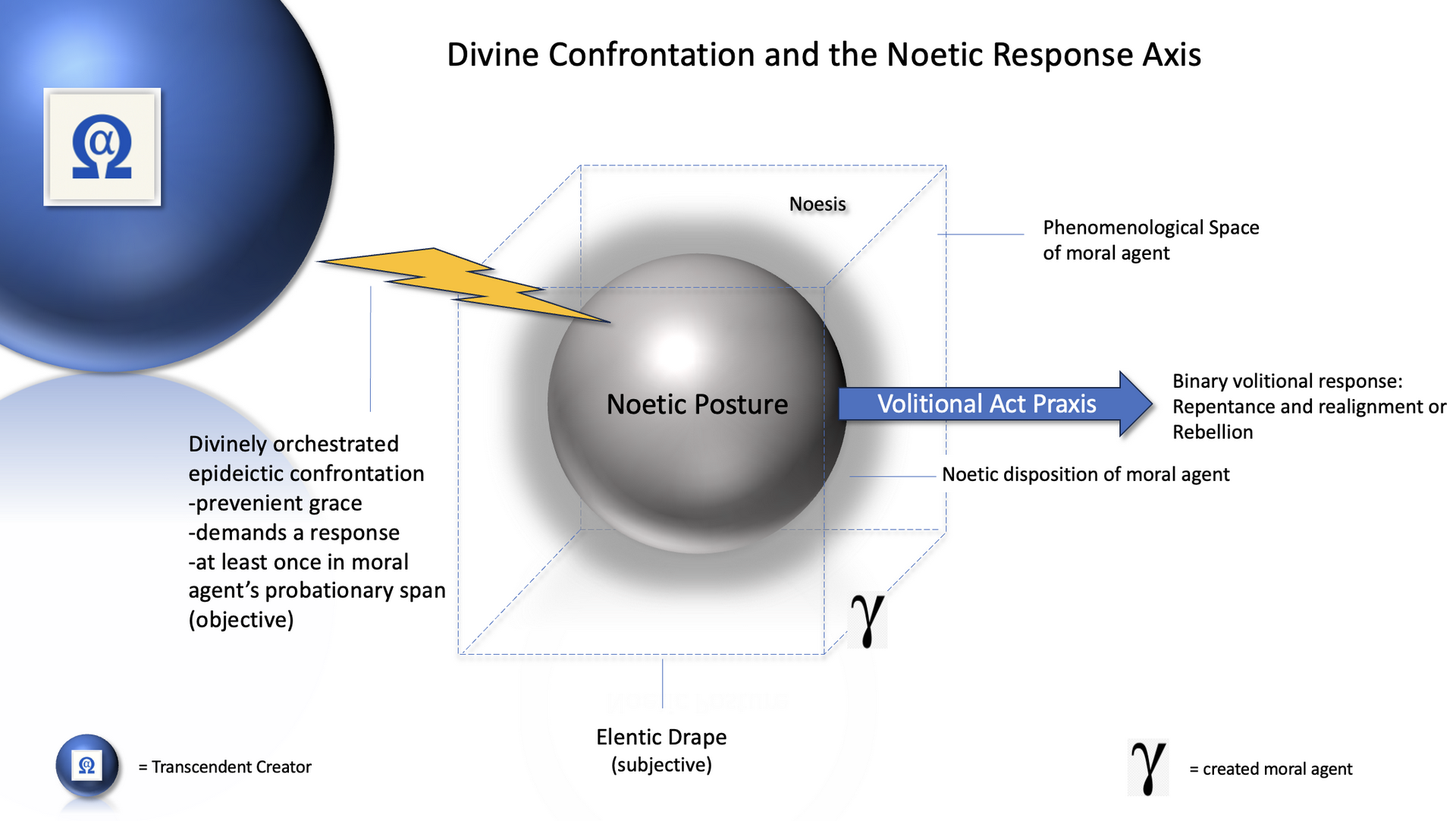

Depicting Divine Confrontation to Exposure: Diagramming the Epideictic–Elentic Moral Axis

The following diagram visualizes the theological structure and phenomenological sequence by which moral truth confronts the human soul. It maps the interplay between noesis, noetic posture, disposition, and volition within the bounded arena of human experience. Framed by prevenient grace, this axis captures the double movement of revelation: the epideictic act by which divine reality breaks in, and the elentic moment in which the agent’s true posture is unveiled. Together, they constitute the moral crisis to which every soul is summoned during its probationary span.

This diagram depicts the moral drama of a human agent’s encounter with divine truth. The Transcendent Creator (α—Ω) initiates a divinely orchestrated epideictic confrontation, an act of prevenient grace that occurs at least once during the moral agent’s probationary span. This confrontation is not merely informational but morally invasive—summoning a response from the agent’s inner orientation. The confrontation enters the phenomenological space of the moral agent, represented by the bounded transparent cube.

Within this space, five interrelated dynamics define the soul’s structure and response. Noesis is the cognitive act of morally perceiving and evaluating truth. Located at the top of the agent’s space, it governs awareness but is influenced by deeper dispositional currents. Noetic Posture refers to the volitional-affective orientation of the agent toward truth. It is the core stance of the soul—receptive or resistant—prior to conscious reasoning. Noetic Disposition is the habituated tendency of the soul toward moral truth, built over time through repeated responses. It frames posture and colors perception, making the agent more tender or more hardened before new confrontation even arises. Volitional Act / Praxis is represented by the outward arrow; it is the executive action of the will—the manifestation of posture into behavior. It leads to either repentance and realignment or rebellion and suppression. Elentic Drape is the moment of internal unveiling. Following the epideictic strike, the agent becomes aware of their own posture: either convicted and drawn, or exposed and hardened. This is where the soul is ontologically exposed to itself. Together, these dynamics illustrate the double movement of divine moral summons: Epideictic, the external revelation of God’s order; and Elentic, the internal disclosure of the agent’s response. The epideictic confrontation is the core revelatory event—the moral summoning of the soul by divine initiative. Yet this confrontation is not monolithic in its form. It is qualified by two further dimensions: Modal Confrontation refers to the tone, force, and manner of divine engagement. Some are confronted with quiet heart-opening (e.g., Lydia), others with dramatic interruption (e.g., Saul). This dimension ranges from gentle invitation to arresting severity. Temporal Confrontation refers to the timing of the encounter relative to the agent’s probationary time. Some receive prolonged illumination (e.g., Nicodemus), others are met at the brink of death (e.g., the thief on the cross). This dimension underscores the urgency or duration of divine allowance within probation. Thus, while the epideictic confrontation defines the event itself, its modal and temporal character shape its form and impact. Divine confrontation is not a singular formula but a calibrated act of moral summoning—tailored to the agent’s posture, history, and horizon. This model affirms that truth is not merely received but confronts; and that the soul’s response is not merely intellectual but ontological—disclosing not just what one thinks, but who one is.

The distinction between epideictic confrontation and elentic exposure is not only philosophically and rhetorically sound, but also textually rooted in Scripture. Several key passages model this twofold moral summons:

Luke 15:17 – “And when he came to himself...”

Elentic threshold: “He came to himself” signals a turning inward, where the soul sees itself truly—not informationally, but ontologically exposed to its own moral condition→ Epideictic exposure leads to elentic awakening.

Romans 1:18–21 → 2:15

Elentic exposure (unveiling): The conscience “accusing or else excusing” (2:15) shows the internal realization of posture—the response to the revealed moral law→ External truth confronts; internal conscience reacts.

Acts 2:37 – “Now when they heard this, they were pricked in their heart…”

Elentic: The people are “cut to the heart”—not merely convinced, but internally ruptured, leading to the question, “What shall we do?”→ External proclamation leads to internal volitional crisis.

Hebrews 4:12–13 – “...all things are naked and opened unto the eyes of him with whom we have to do.”

Elentic: The agent is naked and exposed before God—the soul sees itself in light of divine scrutiny → God's Word discloses truth and unveils the self.

Faith, biblically, is not primarily a cultivated virtue but a response to divine confrontation. It is “the gift of God” (Eph. 2:8, KJV), not the outcome of neutral deliberation. When God confronts, the human agent is summoned into crisis: to yield in reverent humility or to suppress the truth in unrighteousness. This confrontation is ontological, not merely epistemic. It discloses reality as it is, and demands allegiance before it can be systematized.

Thus faith functions as ontological disclosure. It is not an arbitrary leap into the void but a relational unveiling of the order God has already spoken into being. The individual, when confronted, does not construct meaning but is summoned into alignment with meaning already given. Surrender does not invent ontology; it participates in it.

Yet this confrontation plays out differently at personal and structural scales. At the personal level, faith retrofits prior experience: what was once interpreted autonomously is re-seen as disclosure, re-aligned to God’s order. Past perceptions are not discarded but transfigured, integrated into a new ontological coherence. At the civic or national level, however, retrofitting is nearly insurmountable. Systems that begin in rebellion ossify around false ontologies, and reform attempts collapse unless the underlying allegiance is shattered. Grace may reorient individuals by converting their posture, but nations that refuse God’s order cannot simply be “adjusted” by neutral procedure; they must either be reborn through radical alignment or decay under their own fraud.

Newborn estrangement

From the first moment of life the infant inherits Adamic alienation—an ontological posture outside filial communion. Yet the divine image and an embryonic imprint of God’s moral law are already present (Rom 1:19-20; 2:14-15). This latent witness, though unconscious, means the child is estranged but not devoid of God-oriented capacity; separation is real even before words or choices appear.

Non-culpability during latency

Because neurological and moral faculties are not yet awake, the newborn cannot suppress that witness (Rom 1:18) or form intent (mens rea). Alienation therefore carries no personal blame. The child is rightly called a “sinner” ontologically, yet remains non-culpable for lack of conscious rebellion. Scripture confirms that a crooked disposition is woven into the human heart from the earliest stages of life (Prov 22 : 15), underscoring that alienation is not merely acquired behaviour but an ingrained posture in need of redemptive correction.

Awakening and possible suppression

As cognition matures, the innate sense of God progressively rises to awareness; only then does the capacity emerge either to honour or to stifle the truth. At this developmental threshold, epideictic confrontation (God’s self-display in law or gospel) meets elentic unveiling (the Spirit’s exposure of posture) at God’s appointed moment within the agent’s probationary span. Confrontation does not add information; it compels the agent to recognise what was always there. Here moral accountability comes to full term: the heart must bow in humble assent or ratify estrangement by conscious denial—the decisive turn on which culpability pivots.

With the estranged posture unmasked and conscience summoned, we can now trace how the regenerated agent enters willing participation in the moral order.

Even in regeneration, moral agency is preserved. God restores the capacity to obey but does not override it. The regenerate will must consent to moral reality—to allow God’s axiology to define what is good, His commands to frame what is right, and His Spirit to enable what is possible. The soul is invited not to mechanical compliance but to relational fidelity—receiving God’s value, obeying His command, and walking in His enablement.

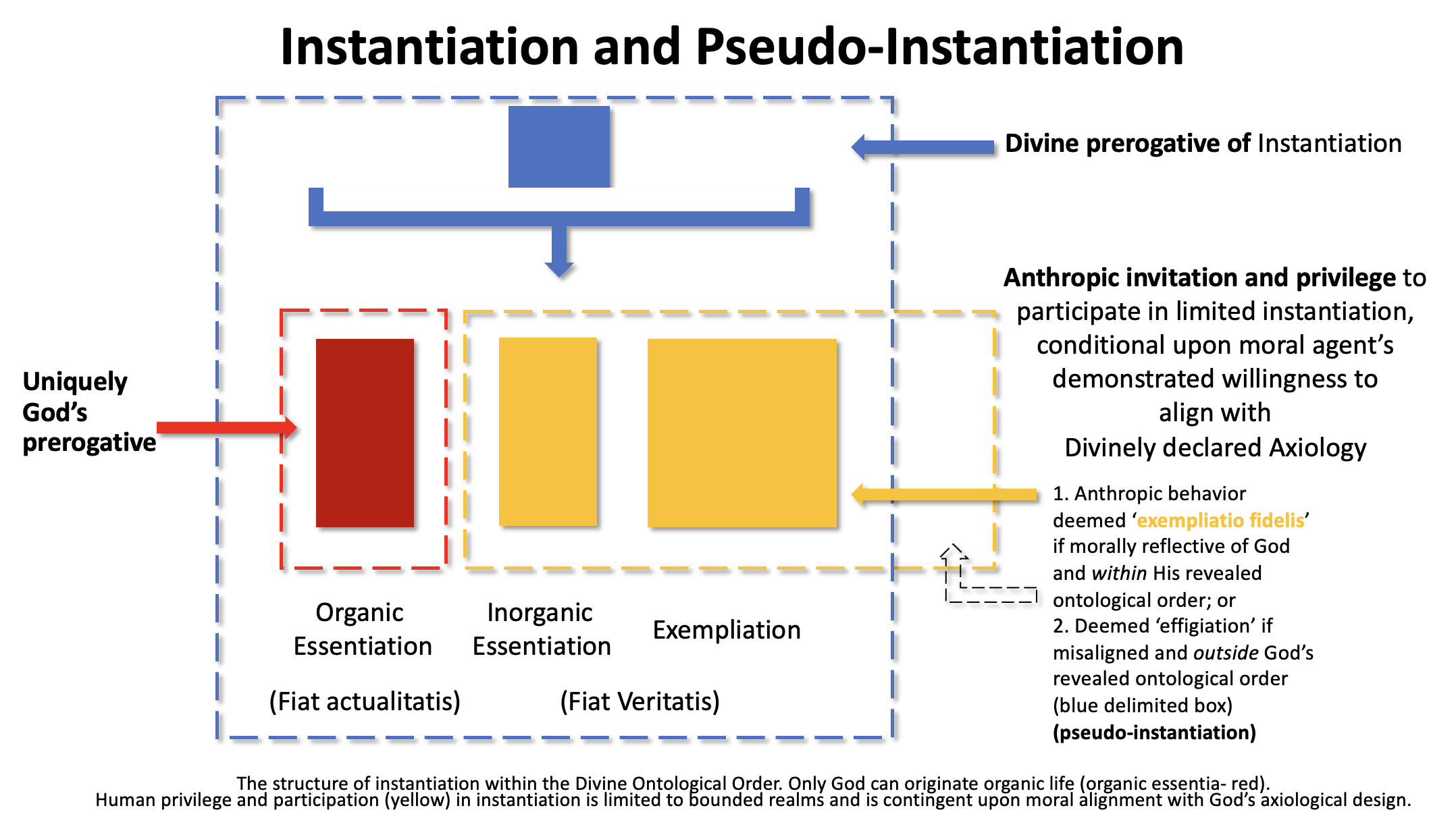

Moral formation, then, is not the internalization of rules, but the progressive noetic and volitional alignment with divine instantiation—God’s sovereign right to define, authorize, and sustain moral reality. This is embodied most fully through exempliation: the faithful instantiation of moral types in personal and relational life (behaviour). In this, the regenerate agent becomes a living witness to divine design—not merely a moral actor, but a mirror of divine character. But fidelity is not limited to individual obedience. It is also expressed through reverence for inorganic essentiation—the ordering of moral reality in structures, roles, and limits. These too reflect divine prerogative and must not be simulated, overridden, or redefined.

Thus, moral formation involves a dual movement: an internal fidelity that aligns with divine summons, and an external reverence that honors God's modal boundaries across all ontic domains. Moral agency is the freedom to respond—to participate or to effigiate, to obey or to simulate. Fidelity, in this light, is not mere correctness but ontological submission to God’s revealed order.

The moral architecture restored through grace does not override the will—it summons it. This relational summons must be met noetically: received as form (alignment of moral perception), intentioned in noēsis (deliberate moral resolve), and expressed in praxeological conduct (embodied moral act).

God remains sovereign, but regeneration still requires consent: “Ye have obeyed from the heart that form of doctrine which was delivered you” (Rom. 6:17). Moral agency, then, is preserved within covenantal obedience; and divine formation is not imposed, but relationally inhabited.

The horizon is where this dynamic is lived: the phenomenological space—the terrain of perception, desire, resistance, and response- has been alluded to above. In this space, the soul must receive moral truth; it cannot manufacture it. Only when rightly related to the One who is can the moral self regain its coherence.

This is not ethics imposed on a neutral anthropology, but a moral articulation of restored ontology. In this model, moral agency is not autonomous construction, but responsive participation in God's design: freedom not to define the good, but to walk in it.

A coherent causal hierarchy of moral action can be conceptualised (post-lapsarian state):

Axiology → Deontology → Modality → Teleological Praxis

This is not a loose association but a moral logic of instantiation: each layer depends on the integrity of the one before it. If value is redefined (axiological fraud), then duty becomes distorted (deontological inversion), which in turn corrupts what is perceived as possible or permissible (modal inflation), leading ultimately to praxis unmoored from value—resulting in ontological fraud (effigiation)

Where secular frameworks collapse or reverse this order—placing praxis first or grounding value in consensus—the biblical model begins with divine value, proceeds through revealed duty, is bounded by God-given possibility, and issues in faithful moral action. This taxonomy is not merely descriptive but causally ordered, revealing how misalignment at any point produces distortion downstream. In a world of moral reconstruction and ideological simulation, only a framework that restores value, obligation, and possibility to their relational, ontological, and covenantal source can yield a coherent moral life. This axiology-to-praxis structure is not a schema imposed on reality, but a map of how reality speaks—revealing both who God is, and who we are called to become in Him

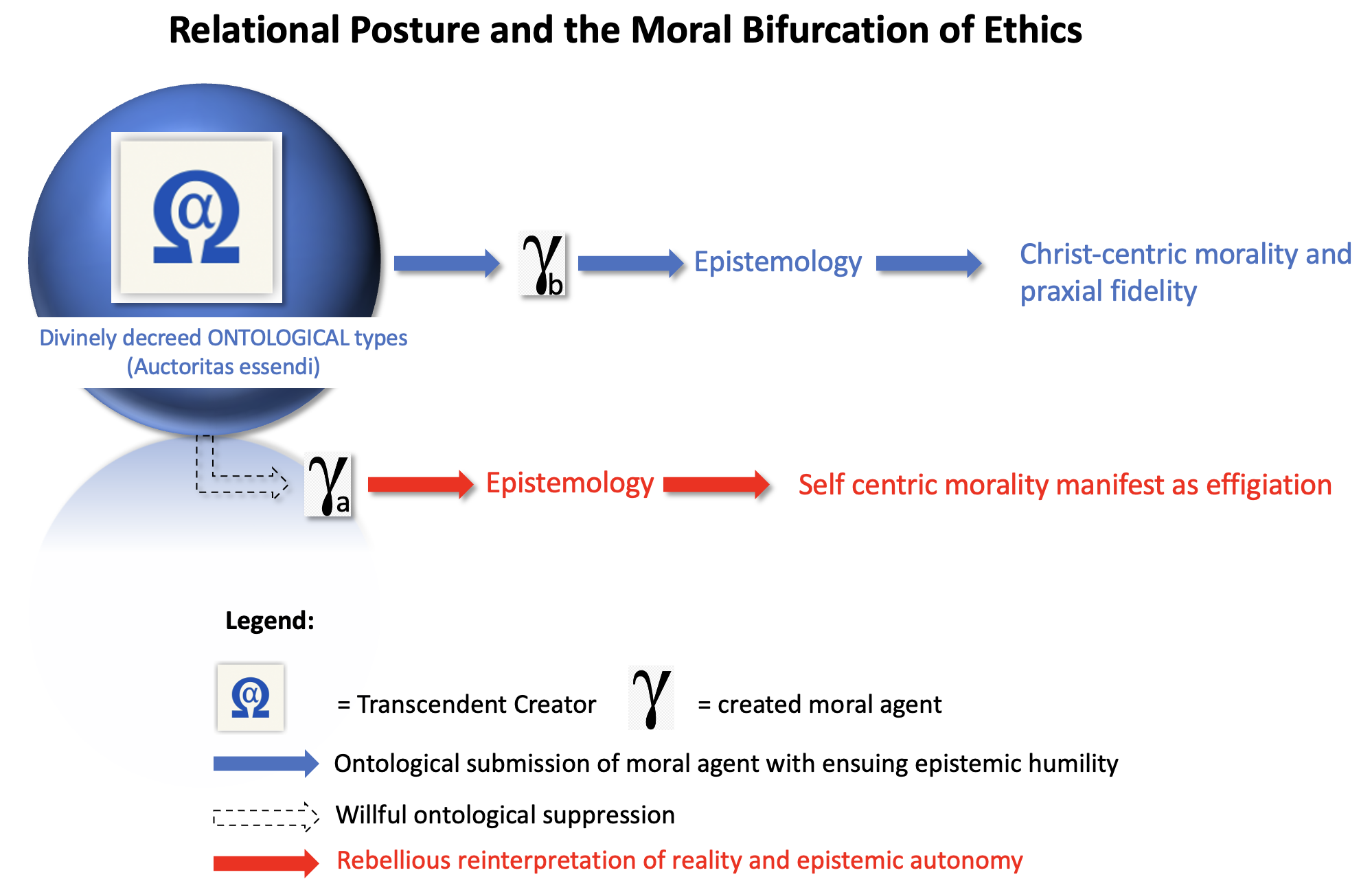

The above diagram illustrates how relational posture toward divine ontological types (γ_a vs. γ_b) determines not only epistemic orientation but the form of morality that ultimately manifests. Ontological submission results in epistemic humility and culminates in Christo-centric morality and praxial fidelity. Wilful suppression leads to epistemic autonomy and ends in self-centric morality, manifest as effigiation. This bifurcation reflects not two parallel systems, but two divergent responses to reality—only one of which aligns with what God has truly instantiated.

Since DM moral structure defines the relational architecture of moral reality, then moral failure is not merely behavioral deviation, but ontological misalignment—a rupture in one’s participation in the order God has defined and authorized. Sin is not just the breaking of a rule; it is a failure to participate rightly in the moral order that God has defined and instantiates. When one suppresses divine axiology, rebels against moral duty, or simulates modal possibilities not given by God, the result is not just disobedience—it is ontological misalignment, a form of moral distortion that bears fruit in simulated praxis.

This distortion can be described in terms of effigiation: the projection of a form that mimics the appearance of moral action, but is unrooted in the ontological reality God has authorized. Effigiation is not mere error—it is moral simulation. It offers the form of goodness, justice, or virtue while severed from the ontological root that makes them real. It is the projection of appearance without participation—an aesthetic counterfeit of obedience divorced from divine authorization.

This moral simulation emerges not suddenly, but through a progression of suppressed axiological confrontation in a non-regenerate moral agent. The soul does not leap into effigiation without first evading the known noetic demands of moral alignment. Effigiation is not the origin of rebellion but its terminus—the common final pathway of resistance. It presupposes a structure already partially resisted, selectively evaded, or progressively sidelined. Even where the DM unit is not fully relationally awakened (pre-confrontation), its ontological presence is not dormant—it is disregarded in part, muted by preference, or partitioned by volitional design.

As such, effigiation is the culmination of suppressed noesis. It flows from postural deviations like suppression, avoidance, compartmentalization, neglect, and finally simulation.

Suppression – Active rejection of moral truth; a conscious pushing down of known obligation (cf. Rom. 1:18);

Avoidance – Indirection or delay in response to moral clarity; evasive deferment rather than outright rejection (cf. Jonah 1:3);

Compartmentalization – Divided moral domains where certain areas are surrendered and others retained in self-rule (cf. Matt. 23:23–28);

Neglect – Passive disregard of truth; failure to heed moral summons due to sloth, apathy, or habituated disengagement (cf. Heb. 2:3);

Effigiation – Simulation of virtue without ontological fidelity; outward moral performance divorced from submission to divine instantiation (cf. 2 Tim. 3:5; Isa. 29:13);

Suppression differs from avoidance in timing: suppression fights a known duty, whereas avoidance sidesteps duty before conviction takes hold. Compartmentalisation is a deliberate partitioning of life-spheres; neglect is merely apathetic decay.

These are not simply psychological evasion tactics; they are ontological refusals. They represent postures that attempt to preserve moral self-rule while avoiding full confrontation with divine fidelity. Suppression, then, is not merely intellectual evasion—it is moral rejection of light. As Paul declares, “they received not the love of the truth, that they might be saved” (2 Thess. 2:10). This implies more than epistemic hesitation; it names a volitional posture—a refusal to cherish what convicts. The soul is not condemned for ignorance, but for recoiling from the invitation to see. Suppression is not only the silencing of duty but the rejection of the One who discloses it. Hence, moral collapse begins not with cognitive error, but with the refusal to love truth—because truth demands surrender.

At the heart of effigiation is pseudo-instantiation: the arrogation of divine prerogatives in the absence of divine authorization. This can occur along all three axes of the DM unit:

Such pseudo-instantiations do not merely diverge from God's will—they parasitize His moral categories, co-opting His language to cloak ontological rebellion in the garb of righteousness. They are not acts of ignorance but simulations of fidelity—efforts to instantiate moral reality without submission to its Source. Effigiation emerges downstream of axiological distortion, deontological inversion, and modal inflation. It is not the beginning of rebellion but its final form—where misalignment crystallizes into simulated praxis.

Instantiation and pseudo-instantiation are depicted in the digram below.

Effigiation mimics the moral shape of fidelity but lacks its root. It creates a moral counterfeit that may appeal to public virtue, institutional legitimacy, or psychological sincerity—but which ultimately stands condemned by its ontological dislocation.

Effigiation is not an accidental feature of modern moral decay—it is its operative mechanism. In a culture that retains moral vocabulary but has severed it from ontological grounding, the ethical landscape becomes populated by pseudo-virtues: compassion without truth, justice without judgment, freedom without fidelity. These are not deficient approximations of goodness—they are structural counterfeits: rhetorically legitimate, but ontologically void.

Effigiation enables and sustains:

Axiological Reversal – the moral inversion warned of in Isaiah 5:20: “Woe unto them that call evil good, and good evil.” Here, value is not merely confused—it is reversed, made to serve antithetical ends while retaining moral labels.

Deontological Inversion – the repackaging of rebellion as obligation, where it becomes a “moral duty” to oppose what God has commanded. Here, counterfeit imperatives cloak opposition in the language of virtue.

Modal Inflation – the presumption of permission under the banner of possibility. What God has not enabled is treated as morally valid simply because it is psychologically plausible or technologically feasible.

What masquerades as moral progress is often ontological simulation: a reconfiguration of moral tokens detached from the source that gives them truth. Effigiation replaces the imperative to obey with the imperative to appear righteous, making fidelity performative rather than participatory.

In contrast to effigiation, fidelity is not mere sincerity—it is ontological allegiance: a faithful participation in the order God has defined, commanded, and enabled. It is covenantal obedience in which:

Value is not felt but revealed and received—a recognition of God's axiological prerogative.

Duty is not constructed but submitted to—a yielded response to divine deontology.

Possibility is not presumed but enabled—a Spirit-governed participation in true moral modality.

Fidelity is not passive assent. It is relationally active obedience, animated by grace, structured by truth, and ordered by love. It is the moral agent’s yes—not to an abstract code, but to the living reality of God's moral kingdom. In fidelity, the soul does not simulate righteousness; it exempliates it.

Within the fallen order, the moral architecture revealed in the DM unit is necessary to mediate the rift between what is good, what is commanded, what is possible, and what is done. Each layer—axiology, deontology, modality, and praxis—emerges in response to the fractured condition of moral disalignment and ontological rebellion against the One True God.

But this scaffold is provisional, not permanent. It reflects a state of moral probation, where the will is divided and conscience must intervene to govern fractured desire.

In a fully regenerated state—whether anticipated in the eschatological horizon or increasingly realized in sanctified life—the original moral ordering is restored. When the axiological core is perfectly aligned to divine love:

The deontic unit becomes redundant, for love and law are no longer distinct.

The modal unit collapses into immediacy, for all that is possible is already harmonized with what is good.

Praxis flows without negotiation, not from duty, but from delight.

This is not the erasure of moral agency—it is its redemption. What was once conscious, deliberative, and strained—scrutinized through commandments and weighed against capacity—becomes subconscious again, as it was in Eden. The soul acts freely not because it is unbound, but because it is perfectly bound to what is good.

"Thy will be done in earth, as it is in heaven." (Matthew 6:10)

In heaven, God's will is not resisted—it is rejoiced in. The moral architecture is ontologically preserved, but phenomenologically dormant. Not abolished, but transfigured—its lines no longer traced, but lived. This is not the abolition of ethics, but the consummation of moral being. Dormant does not mean absent. Moral agency persists—now effortless rather than contested. The will remains free and accountable, but obedience flows spontaneously from perfected desire (cf. Rev 14:5; 1 John 3:2).

Even now, all true moral alignment involves not only external obedience but internal exempliation—expressed both in noetic posture (contrition, trust, humility) and praxeological fidelity. In a fully regenerated state, this exempliation becomes subconscious, animated not by compulsion or calculation, but by congruence with divine love.

What began as a scaffold for judgment is transfigured into the invisible architecture of love. The DM unit remains as a map—but the regenerate will, realigned to divine axiology, no longer consults the map. It walks the path by heart.

The diagrams below compare and contrast the pre- and post-lapsarian economies.

From Intuitive Flow to Mediated Duty

In the Prelapsarian order (top slide), moral agents operated in direct axiological alignment: purpose flowed seamlessly from value without tension.In the Postlapsarian economy (bottom slide), however, moral unity is disrupted—requiring volitional engagement, obligation, and modal navigation to recover moral clarity.

Morality, within this framework, is not merely behavioral compliance or social convention—it is ontological fidelity to divinely delimited kinds. Each moral claim or act can be refracted through the seven ontotype criteria:

Fixity affirms that moral good is not fluid or evolving, but grounded in immutable kinds.

Integrity binds action to motive and kind, exposing dissonance between external behavior and internal orientation.

Parsimony guards against inflated or artificial moral constructs not warranted by revelation.

Typological Convergence ensures that righteous action harmonizes with other divine kinds—truth, justice, mercy, holiness.

Modal Implication recognizes that every moral act is not merely behavior but a possible or necessary instantiation of a divine kind.

Telic Vector orients moral action toward God's redemptive ends, never toward self-referential virtue.

Divine Assignment reminds us that only God defines the good, and all moral claims must submit to His revealed order.

In short, morality is not conceptually constructed—it is ontologically disclosed, covenantally assigned, and relationally inhabited. Any ethic not rooted in this structure is a pseudo-type—externally persuasive, but ontologically void.

Once ontology is properly aligned as the foundational ground of truth, the debate between moral relativism and moral absolutism is automatically resolved. This follows from the integral relationship between being and truth, where the divine nature of reality serves as the unchanging reference point for all moral standards. The key points are as follows:

Moral Truth is an Ontological Kind Grounded in the Divine: Moral truth is not subject to human perception, cultural norms, or individual experiences. Instead, it is rooted in the divine nature of reality, which is unchanging and objective. Since God's nature is inherently good, just, and holy, the moral order becomes an ontological kind—a necessary, intrinsic category of being. Therefore, moral laws are absolute and universal, grounded in the ontological essence of the One True God—it isn’t just a human construct, but an inherent part of the ontological fabric of the universe.

Moral absolutism is the necessary consequence of ontological absolutism, as moral truths are not malleable or relative to the observer but are objectively fixed and intrinsically aligned with the unchanging nature of being. Morality is not arbitrary; it is a reflection of God's eternal and unchanging nature.

Epistemology Recedes into Discernment: Once the ontological framework is rightly established, epistemology recedes in importance (see Epistemology essay). Epistemology becomes a tool for aligning human understanding with the objective, revealed moral truth, rather than constructing or shaping it. Moral truth is revealed in the divine order, not constructed by human perception.

Therefore, the subjectivity and uncertainty that give rise to moral relativism are nullified because they stem from a flawed epistemological foundation. With epistemology subordinated to the ontological truth, moral relativism has no ground to stand upon.

Moral Relativism Becomes Incoherent: Since moral truth is objectively anchored in the divine and immutable nature of God, moral relativism—whether it is cultural relativism, moral subjectivism, or contextual moralism—becomes philosophically incoherent. It cannot hold up in a framework where truth is ontologically fixed, and all perspectives, values, or judgments are ultimately subordinate to divine revelation.

The argument that "truth is relative" collapses, as epistemic relativism—rooted in the subjective shaping of truth—becomes untenable once truth is anchored in ontological absolutes. As a result, moral relativism loses its viability, and there is no longer any epistemic space where morality can be arbitrarily shaped or adjusted.

Morality does not need a new system to patch the old ones; it needs its lost ground. Ethics is participatory before it is procedural, ontological before it is performative. The Deontic-Modal imprint is no abstract scaffold but the creaturely reflection of divine order. Effigiation is therefore not a harmless variation—it is ontological fraud. Fidelity is more than sincerity; it is the yielded self rightly aligned to the One who defines what may be.

Within our fallen economy duty must precede comprehension, not because deon outranks telos, but because purpose is rediscovered only through obedient posture. Yet this sequence is provisional. In the restored order—prefigured in Eden and promised in glory—duty and purpose converge. The soul no longer obeys to understand; it understands because it is already aligned.

There, deon and telos are synchronous, not sequential: a single harmony of moral being. Participation is no longer a matter of calculation or compliance but of effortless congruence with divine life.

Such is the recovery of moral existence: ethics no longer imposed from without, but ontology restored from within.

Summary

In this section, we traced the collapse of moral coherence from its historical roots—the fracture of duty from purpose, the false dichotomy between divine and natural law, and the rise of moral constructs divorced from ontology. Against this background, we recovered a biblical moral framework rooted in divine axiology, deontic obligation, and modal enablement. We presented the ADM structure as the relational architecture of moral life, grounded in God's character and sustained through grace. Finally, we exposed the ontological distortion of moral effigiation and affirmed fidelity not as moral performance, but as participatory alignment with divine instantiation—exempliative and creational. The moral life, then, is not merely about doing good, but about being rightly aligned with what God has willed to be real.