(A Biblical Exposition on the Corollary of Annulment)

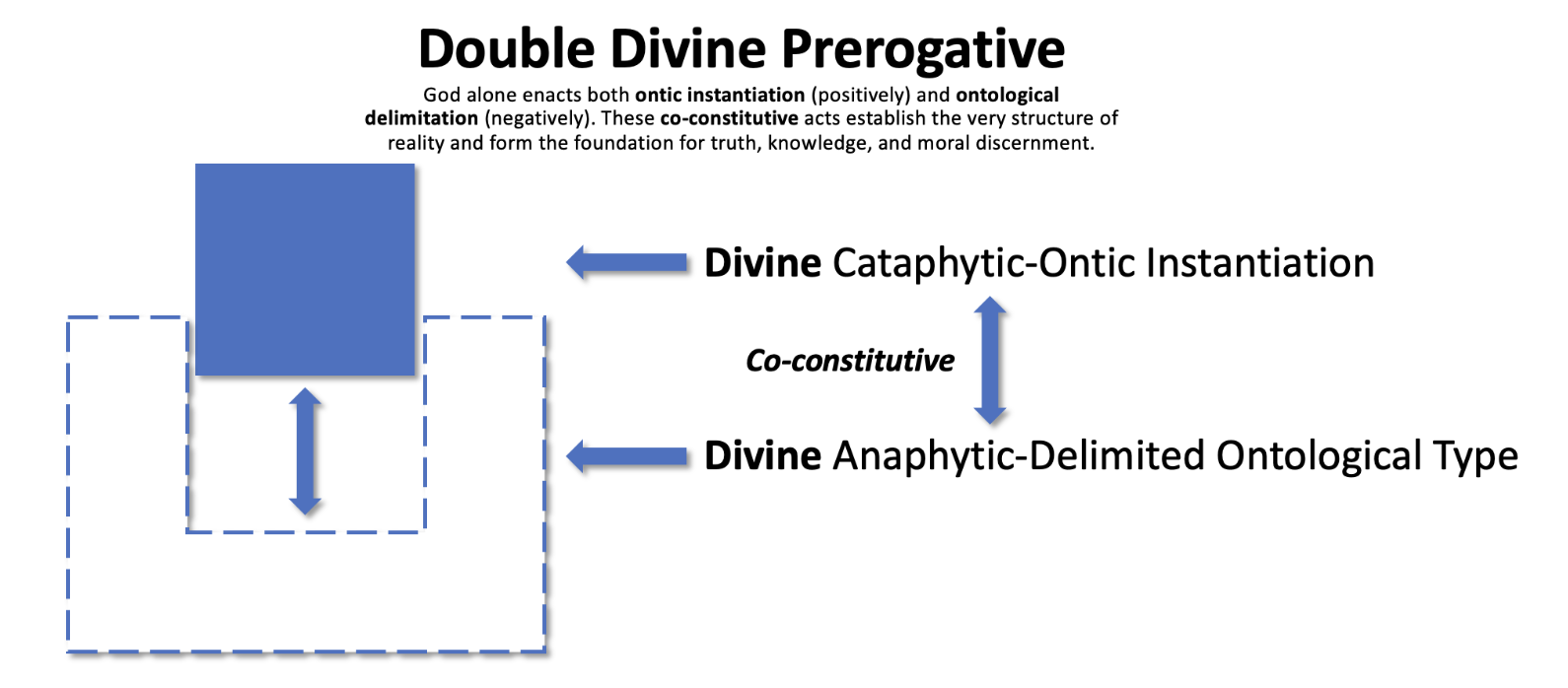

This Supplementum extends—but does not alter—the established doctrine of the Divine Double Prerogative (DDP)- see Ontology Part I . Scripture discloses that the prerogative by which God defines (auctoritas essendi) and instantiates (auctoritas instantiandi) all being necessarily entails a third: the prerogative to annul (auctoritas annullandi) —to withdraw existence that has willfully rebelled against truth.

This insight emerges directly from Christ’s teaching on judgment. It reveals that divine judgment is not arbitrary punishment but ontological rectification—the withdrawal of life from that which refuses correspondence with divine order—the seven-fold justice of God that restores rather than retaliates (cf. Appendix E6 ). The resulting triadic symmetry—definition, instantiation, and annulment—completes the moral ontology of divine governance and clarifies the distinction between God’s ontological jurisdiction and humanity’s relational jurisdiction.

Two sayings of Jesus seem, at first reading, to stand in opposition:

“Judge not, that ye be not judged.” (Matt 7 : 1)

“You shall know them by their fruits.” (Matt 7 : 16)

The first forbids judgment; the second requires it. The tension dissolves when we recognise that Scripture differentiates between relational–personal discernment and judicial–final adjudication. The former is creaturely participation within divine order; the latter is divine prerogative over being itself. (See Appendix E6 ).

Relational–personal discernment operates within the sphere of moral stewardship. It is the vigilance by which believers remain in the world yet not of it—testing spirits, discerning truth from error, and recognising fruit without usurping divine authority (1 Thess 5 : 21; John 17 : 15–18). This is judgment in its relational mode: the recognition of correspondence and the preservation of purity within fellowship. Here the believer “walks in the Spirit,” allowing moral discernment to restore rather than condemn (See Appendix C2 ).

Judicial–final adjudication belongs solely to God, “for the Father has given all judgment unto the Son” (John 5 : 22). It is the right to pronounce ultimate worth or condemnation—to sustain or to withdraw being itself. When humans condemn, they cross from relational discernment into ontological presumption, attempting to exercise auctoritas annullandi.

Thus, Christ’s two injunctions are not contradictory but complementary. “Judge not” preserves reverence toward divine jurisdiction; “know them by their fruits” preserves relational fidelity within creaturely vocation. Together they describe the posture of covenantal faithfulness: to perceive truly without presuming divinity.

This distinction may also be visualised as a two-axis hierarchy of judgment. The divine mode is vertical—judicial and ontological—flowing from Creator to creation. In God Himself there is no information asymmetry: His knowledge of being is immediate and entire. Yet divine judgment is manifestationally investigative—not to discover, but to disclose; not because God learns, but because creatures must see. The investigative phase is therefore revelatory: it confronts creation with the moral transparency of its own state. The human mode is horizontal—relational and moral—operating among finite persons within time. Here, information asymmetry is inevitable; we perceive partially and must discern humbly. The vertical governs being; the horizontal governs fellowship. Moral coherence is preserved only when these axes remain distinct yet aligned, intersecting at the point of covenantal obedience where humility meets truth.

For the sake of conceptual precision, this framework extends the vocabulary first employed by Van Til, who spoke of anaphatic delineation and cataphatic instantiation as complementary poles of divine communication. See Ontology part I.

Here a third, apophatic disannulment, is proposed—not as revision but as completion—acknowledging that the same God who defines and affirms being also reserves the right to withdraw its corrupted instance. The triad thus provides a full grammar of divine speech: definition, affirmation, and rectification.

The biblical motif of dispersion reinforces this harmony. God scatters His people among the nations (Gen 11; Acts 8 : 1; 1 Pet 1 : 1) that they may witness through presence without conformity. In dispersion the community must continually discern its environment while resisting the urge to condemn it. Discernment guards identity; mercy guards love. Thus, the Church in exile enacts on the human plane what God demonstrates on the divine: relational awareness within time, final judgment reserved to eternity. When institutions attempt to enforce a pseudo-universal “greater good” they risk collapsing these axes—converting horizontal prudence into a counterfeit vertical prerogative (See Appendix E9 ).

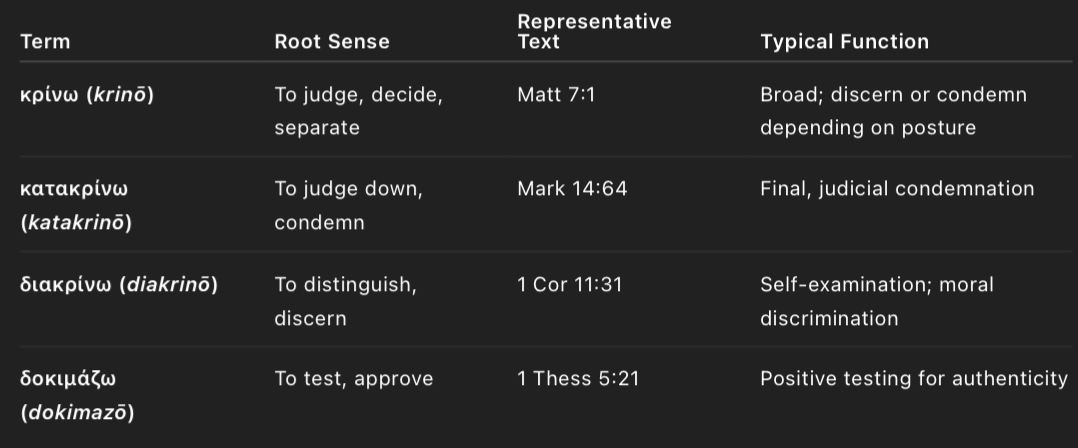

The New Testament employs several related verbs for “judging,” each carrying a distinct shade of meaning. Understanding their nuance is essential to grasp Christ’s teaching:

In the Sermon on the Mount, Christ’s use of krinō approaches the condemnatory sense of katakrinō—the usurped act of final judgment. Yet elsewhere believers are commanded to diakrinō and dokimazō: to discern and to test. The issue, therefore, is not the act of judgment itself but the jurisdiction of the judge.

Human beings are called to dokimazō—to test all things and approve what is good. Only God may katakrinō—to pronounce final condemnation and withdraw being. Confusing these levels produces either moral paralysis (when discernment is suppressed) or spiritual arrogance (when annulment is presumed). The proper exercise of discernment is thus both an act of humility and an act of obedience.

he same pattern appears in Scripture’s epideictic and elentic moments—when the law exposes rather than condemns (Appendix C2 ; Appendix E6 )—illustrating diakrinō and dokimazō in practice.

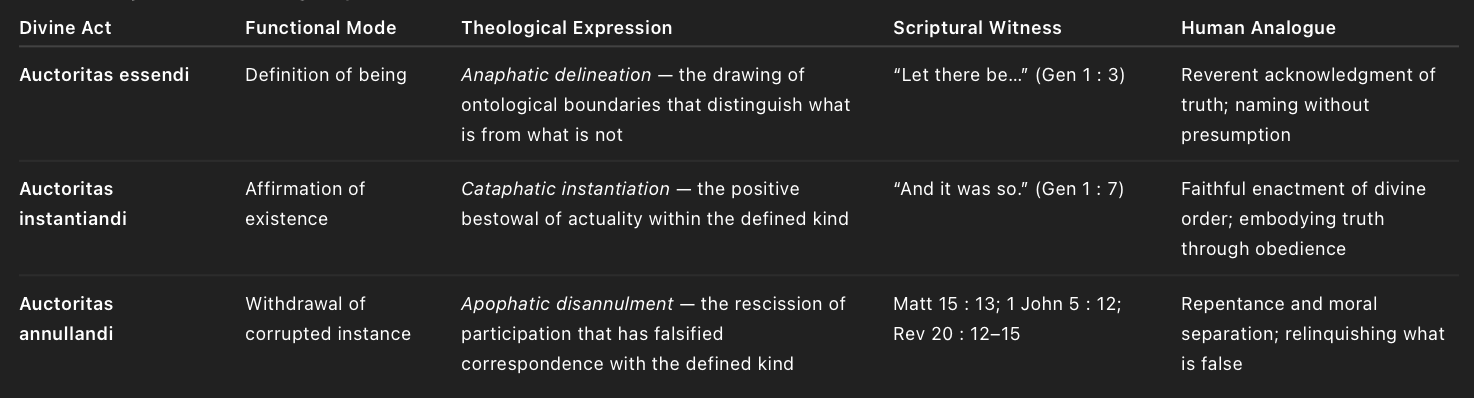

The biblical narrative itself unfolds the sequence of divine prerogatives. Each expresses a distinct aspect of the Divine Authority by which reality is spoken, sustained, and, when necessary, rectified.

Auctoritas essendi — the authority to define what is.

“Let there be …” (Gen 1 : 3)

God alone determines essence and category; definition is His creative word, an act of anaphatic delineation—the drawing of boundaries that separate being from non-being and order from chaos.

Auctoritas instantiandi — the authority to make real what He has defined.

“And it was so.” (Gen 1 : 7)

God alone confers actuality upon what He declares; existence is participation in His will. This is cataphatic instantiation—the positive affirmation of being into form and function.

Auctoritas annullandi — the authority to withdraw rebellious being.

“Every plant which My heavenly Father hath not planted shall be rooted up.” (Matt 15 : 13)“

He that hath not the Son hath not life.” (1 John 5 : 12)

Annulment is not destruction for its own sake but the rectification of reality—the removal of existence that has willfully severed correspondence with divine order. While auctoritas annullandi is eternally inherent in divine sovereignty, it is not exercised as a matter of course. God’s right to annul is constant; His act of annulment is selective and rectificatory—invoked only when continued allowance of rebellion would perpetuate disorder. Scripture portrays a patience that is neither weakness nor delay but purposeful restraint: “The Lord is not slow to fulfil His promise … but is patient toward you.” (2 Pet 3 : 9) Yet divine toleration, forbearance, and mercy must, justly, give way to justice. When the moral crisis of rebellion has ripened beyond remedy, mercy itself demands rectification. At that point God’s sovereign patience yields to decisive judgment—not as reaction, but as the final act of ontological fidelity.

These three prerogatives correspond to the three modalities of divine utterance: anaphatic delineation, by which God defines what is; cataphatic instantiation*, by which He affirms it into being; and apophatic disannulment, by which He withdraws existence that has falsified correspondence with the defined kind. In this act of withdrawal, God does not destroy the kind itself—definition remains inviolate—but removes the corrupted instance that has ceased to participate in truth. Annulment therefore purifies ontology rather than negates it: it rescinds the counterfeit without erasing the category, restoring creation to correspondence with its archetype.

These three prerogatives—definition, instantiation, and annulment—thus form the triptych of divine sovereignty: the articulation, realization, and purification of being. Creation issues from truth, participation abides in truth, and annulment purifies from rebellion.

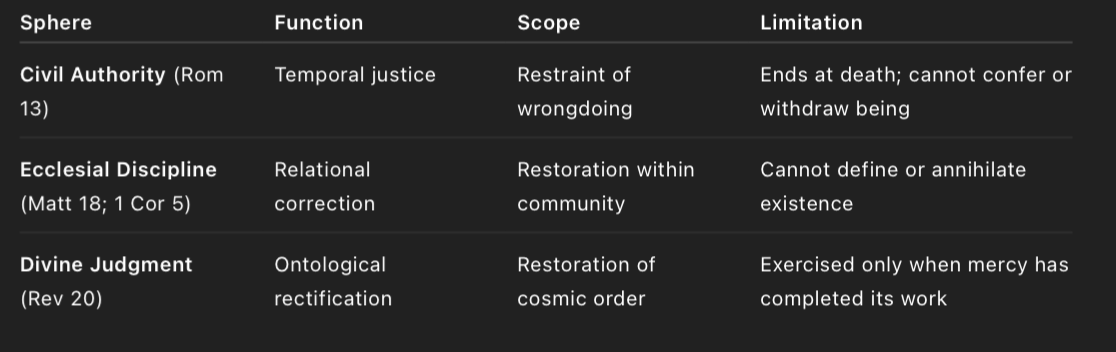

Scripture consistently distinguishes relational boundary from ontological annulment. Human communities may act within the sphere of relationship—correcting, separating, restoring—but never within the sphere of being itself.

Ecclesial discipline (Matt 18 :15–18; 1 Cor 5:5–7) establishes boundaries for the sake of restoration. “Handing one over to Satan,” in Paul’s idiom, exposes rebellion to its consequences that repentance might be born. Such measures are relational correctives, never metaphysical sentences; they regulate fellowship, not existence.

Civil judgment (Rom 13:1–4) restrains injustice within temporal society. The magistrate bears the sword for order, not for ontology. His power ends with life’s threshold.

Modern institutions often claim to act for the “greater good,” but such calculus frequently oversteps the bounds of relational jurisdiction. As Appendix E9

observes, when the state or collective presumes to define or annul personhood in pursuit of abstract utility, it imitates the divine prerogative illegitimately. The moral community must therefore distinguish relational correction from ideological effigiation—the human simulation of divine authority.

The measure of holiness, therefore, lies not in dominion but in proportion—acting where relation permits, and yielding where being belongs to God alone.

Divine annulment, by contrast, transcends both. It addresses not behaviour but being: the withdrawal of life-participation itself when rebellion has become ontologically incoherent.

Believers scattered among the nations enact this same principle of proportionate jurisdiction. Their presence is mandated; their conformity forbidden. The Church dispersed (Gen 11; Jer 29; Acts 8:1; 1 Pet 1:1) must discern its surroundings without condemning them. In its social posture—in the world but not of it—the community mirrors the divine rhythm: patience preceding judgment, witness preceding withdrawal. The call to holiness is therefore not an invitation to isolation but to rightly scaled jurisdiction—governing conduct, not essence.

Because God’s act of annulment is selective and rectificatory, Scripture portrays it in two temporal modes: proleptic and eschatological.

Proleptic Withdrawal God sometimes allows rebellion to disclose its own futility within time.

“God gave them over to their desires.” (Rom 1 :24–28)Such episodes are judgments of exposure, not extermination—moments when divine forbearance momentarily recedes so that self-chosen separation may reveal its emptiness. Likewise, “this is the judgment, that light has come into the world, and men loved darkness” (John 3 :19). These unveilings are anticipatory: they demonstrate within history what final separation will entail, yet they remain reversible through repentance.

Eschatological Annulment Ultimately, a definitive act of rectification awaits:

“A day is fixed when He will judge the world in righteousness.” (Acts 17 :31)“The dead were judged… and anyone not found written in the book of life was cast into the lake of fire.” (Rev 20 :12–15)Here divine toleration, forbearance, and mercy, having completed their redemptive work, give way to justice fulfilled. Annulment at the end is not arbitrary annihilation but the formal restoration of ontological harmony—the removal of rebellion from the order of being. It consummates what patience began: the full purification of creation.

Thus, in both temporal and final forms, annulment manifests the same divine fidelity—mercy that has reached its righteous terminus.

This two-fold temporal rhythm mirrors the distinction between four-fold human restitution and seven-fold divine rectification (Appendix E6 ): the first restores relation within time, the second restores ontology beyond it. The proleptic exposures of history—moments when light reveals darkness (John 3:19)—echo the epideictic function described in Appendix C2 , disclosing posture before final judgment.

Perceive fruit. (Matt 7 :16) Observe conduct and outcome.

Test confession and practice. (1 John 4 :1) Compare profession with deed.

Establish relational boundaries. (Gal 6 :1; 2 John 10–11) Guard fellowship without presumption.

Refrain from final verdict. (1 Cor 4 :5) Leave judgment to God’s appointed time.

Seek restoration. (2 Cor 5 :18–20) Every act of discernment aims toward reconciliation.

This sequence embodies the creature’s proper posture: active moral perception joined to ontological humility.

See Appendix E9 for applied analysis of how institutional or political appeals to the “greater good” risk transgressing these jurisdictional boundaries.

Human judgment is relational and provisional; divine judgment is ontological and final.The first protects the integrity of fellowship; the second restores the integrity of creation.To blur their boundaries is to commit the primal sin of presumption—to attempt the government of being rather than obedience within it.

The Divine Triadic Authority

Essendi — to define what is.

Instantiandi — to make it real.

Annullandi — to withdraw being that willfully rebels against divine order.

In every act of divine governance, anaphatic delineation fixes the bounds of reality, cataphatic instantiation confers existence within those bounds, and apophatic disannulment purifies the field of being from falsified embodiment. God does not erase the kind He defined; He removes the instance that has betrayed its correspondence. Thus, judgment is not annihilation but rectification—mercy brought to justice, restoring the harmony of creation to its archetype.

For the moral creature, the same triadic rhythm becomes the pattern of obedience:

to discern rightly (acknowledging divine definition),

to embody faithfully (enacting divine affirmation), and

to renounce falsity (yielding to divine purification).

All human judgment remains relational and provisional; only the Creator may call being forth—or call it back.

The Triadic Authority discloses not only the structure of divine action but the vocation of the creature within it. Every movement of faithfulness—whether spoken in confession, embodied in obedience, or expressed in repentance—rehearses in miniature the same rhythm by which God governs being.

Anaphatic Confession — The Human Response to DefinitionTo confess is to acknowledge the boundaries that God has drawn: to name light as light, truth as truth, life as life. In confession the believer mirrors anaphatic delineation, accepting the distinctions that sustain order and refusing the semantic drift of rebellion. This posture restores reality through speech that corresponds.

Cataphatic Obedience — The Human Response to InstantiationTo obey is to enact what has been confessed. Obedience participates in cataphatic instantiation—the positive embodiment of divine order in conduct and vocation. Here, truth becomes lived form: moral reality translated into time and action. Such obedience is not mechanical compliance but the joyful consent of being to its source.

Apophatic Repentance — The Human Response to DisannulmentTo repent is to allow God to withdraw what is false within oneself. Repentance analogically reflects apophatic disannulment: the purging of corrupted participation so that life may be restored to correspondence. The believer does not annihilate what was created good but surrenders the falsified instance—the mis-formed act, the counterfeit motive—to divine rectification.

Thus, confession, obedience, and repentance together form the covenantal rhythm of sanctification—the human echo of divine speech. Each moment of integrity or surrender participates in the same cosmic grammar: delineation, instantiation, purification.

When divine toleration, forbearance, and mercy finally, and justly, give way to justice, that act will not contradict the character of God but fulfil it. For the same love that sustains creation will, at the end, also purify it. The hand that formed being will not hesitate to heal it, even through judgment; the voice that once said “Let there be” will say at last, “Be no more”—not in anger, but in truth.

Thus the Supplementum closes not with speculation but with symmetry:

Being begins in mercy, endures by mercy, and is judged by mercy.

The authority to define, instantiate, and annul belongs to God alone; the duty to discern, embody, and repent belongs to His creatures.

In that ordered relationship lies the peace of creation and the hope of its restoration.

Footnote*

The terms anaphatic delineation and cataphatic instantiation are used here in a formalised sense extrapolated from Van Til’s distinction between negative and positive theology. Van Til himself employed the anaphatic–cataphatic polarity chiefly in the epistemic domain; this framework extends the same logic into the ontological register for the sake of structural completion.