This appendix addresses key theological controversies and interpretive tensions that naturally arise in dialogue with the relational-ontological framework presented throughout this project. It is not intended as a polemic, but as a clarification of contrasts—with particular attention to doctrines such as prevenient grace, moral agency, divine judgment, and predestination. By examining these issues in light of relational accountability and scriptural justice, the aim is to preserve both the coherence of divine action and the integrity of human response. Each section proceeds thematically, engaging contrasting theological positions while grounding responses in scriptural and ontological analysis. This appendix also provides philosophical structure beneath prior theological themes.

This section sets up the core problem: how competing systems handle grace, volition, and judgment—and whether God’s justice holds up under scrutiny.

Question: In the parable of the Prodigal Son, what does the Arminian model posit is happening during the period of rebellion—especially at the “swine trough” moment—and how does this differ from the relational-ontological framework proposed here?

In classical Arminian theology, prevenient grace is conceived as a universal divine influence extended to all people, functioning primarily to:

Offset total depravity by softening the heart;

Restore moral and rational capacity;

Enable a free response to God—though not guarantee it.

In this framework, the “swine trough” moment (“he came to himself,” Luke 15:17) represents a self-generated realization, made possible by this restored capacity. The moment is not generally understood as a divinely orchestrated or referential confrontation, but as the point at which the moral agent begins to act upon their awakened faculties.

Grace here is ambient and permissive—it surrounds the will with possibility but does not directly impose crisis. It makes response possible, but does not summon or obligate it.

Volition is seen as naturally free once grace has lifted the disabling effects of depravity. The moral weight of the moment lies not in a specific referential truth confronting the soul, but in the soul's use of its restored faculties. Confrontation, if it occurs, is typically seen as a byproduct of awakening—not its cause.

In contrast, the relational–ontological framework presents prevenient grace not as a general enabling influence, but as God’s sovereign prerogative to confront the soul with ontologically instantiated truth—truth established by Him and relationally aimed at the moral will. This grace:

Is not merely permissive, but places the soul under obligation;

Is not ambient or dispositional, but referential, covenantal, and morally charged;

Does not wait passively, but culminates in a providentially timed moral summons.

The “swine trough” moment (Luke 15:17) is therefore not an emotional nadir or a self-generated realization. It is an epideictic disclosure—a divinely initiated unveiling in which the soul is shown the truth of its condition and confronted with the memory of what is good, ordered, and lost. The phrase “he came to himself” does not signal internal authorship, but marks a kairotic rupture: a moment of volitional arrest, when relational truth is disclosed and moral obligation imposed.

In this model, the will is never passive. Even in rebellion, it is active in suppression (Rom. 1:18). Prevenient grace does not merely make right choice available—it precipitates a reckoning by rendering truth morally unavoidable. Once truth is epideictically revealed, the soul enters the elentic threshold: a morally clarified state of exposure in which the subconscious noetic posture is brought to light. Here, the will must either align with unveiled truth or suppress it anew.

This is not coercion, but confrontation; not manipulation, but moral summons—an invitation to reconstitution through surrender, not compulsion.

Thus, prevenient grace is not “irresistible” in a deterministic sense, but inescapable in its confrontation—a divine prerogative that brings every soul to the crisis of recognition. The pigpen does not regenerate; it unmasks. It does not sanctify; it exposes. And this epideictic exposure cannot be sidestepped—it must be answered. The will, caught in the light, faces its own condition. That response—yielding or resisting—is the elentic moment. The threshold is not epistemic, but ontological and moral.

The divergence between the Arminian and relational-ontological models carries significant theodictic weight—raising the question: On what grounds does God judge justly?

In the classical Arminian framework, prevenient grace enables the possibility of response but does not necessarily entail an epideictic confrontation with ontologically grounded truth. The soul may be morally awakened, but not necessarily summoned by a referential crisis. This opens the theoretical possibility that a person might drift into condemnation without encountering a decisive volitional threshold—a risk that raises procedural questions about the fairness of judgment (cf. Matthew 25:24–27, where the condemned servant pleads ignorance, yet is held accountable for neglect).

By contrast, the relational-ontological model affirms that prevenient grace culminates in a morally and referentially fitted confrontation: a providentially appointed crisis in which the will is not merely enabled, but summoned and obligated [i.e., epideictic exposure yielding an elentic threshold]. Here, judgment is not anchored in what one could have done hypothetically, but in the soul’s actual response to relationally instantiated truth.

This secures the coherence of divine justice: no person is judged apart from a moment of volitional summons; no soul is condemned for abstract failure, but for willful misalignment with truth when relationally confronted.

In this framework:

Condemnation is never arbitrary—it flows from active suppression, not passive ignorance.

Grace is never coercive—it initiates, confronts, and clarifies, but never overrides.

Judgment is not informational but relational—rendered according to posture, not propositional familiarity.

The relational-ontological structure thus safeguards the righteousness of divine judgment and the freedom of the human will. Grace confronts. The will responds. And the judgment rendered is not procedural abstraction but a morally fitting consequence of ontological exposure.

Before the moment of divine confrontation initiated by prevenient grace, the creature is not abandoned but permitted to act according to the trajectory of their own will. This period unfolds under the governance of God's antecedent and consequent will, in which the person’s choices begin to manifest the soul’s latent moral orientation. As Psalm 81:12 states, “So I gave them up unto their own hearts’ lust: and they walked in their own counsels.”

This is not divine indifference, but a form of judicial restraint and relational testing, wherein:

The soul’s inclinations are exposed;

Suppression of truth may deepen (Rom. 1:18);

And a moral pattern emerges—not assumed, but traced—by providence.

This preparatory window preserves the justice of God’s later confrontation. The volitional summons that comes through prevenient grace is not imposed upon a passive agent, but directed toward a will already in motion—a moral will that has resisted, deferred, or sought autonomy. The confrontation, when it arrives, is not arbitrary; it is epideictic, relationally and judicially fitted to the soul's prior trajectory.

In this way, God's justice is upheld without suppressing agency. Divine confrontation becomes not an intrusion, but a climactic disclosure—a morally fitted unveiling of what the soul has become, and what it must now answer to.

Both Arminian and relational–ontological theology affirm that sanctifying grace—the grace by which the soul is conformed to the divine moral order—does not begin its transformative work until volitional consent is given. However, the nature and function of prevenient grace differ substantially across theological frameworks, shaping how each system understands moral responsibility, transformation, and divine judgment.

In classical Arminian theology, articulated by Jacobus Arminius (d. 1609) and the Remonstrants (1610), prevenient grace is understood as universal, enabling, and resistible. It is extended to all people as a means of offsetting the effects of total depravity, thereby restoring the capacity to respond to the gospel. However, it is not equivalent to regeneration, nor does it carry the weight of direct moral confrontation. It merely prepares the will to respond, but does not bind it to a decisive ontological summons. Sanctifying grace is acknowledged within Arminian thought, but is typically treated as a continuation of saving grace after justification—without being defined as a distinct ontological phase or volitional moment of reckoning.

Wesleyan theology, following the work of John Wesley (1703–1791), further develops these categories, offering a triadic schema: prevenient grace, justifying grace, and sanctifying grace. In his model, prevenient grace awakens the soul; justifying grace (forensically) pardons and reconciles; and sanctifying grace purifies and conforms. However, even within Wesleyan Arminianism, the grace that precedes faith remains resistible, and the transitions between stages are often articulated in pastoral or experiential terms, rather than through a precise ontological or judicial architecture.

By contrast, Calvinist theology rejects the concept of prevenient grace altogether. In the Calvinist model, grace is given only to the elect, and it acts irresistibly to regenerate the heart prior to faith. Sanctification is viewed not as a covenantal consequence of volitional consent, but as the necessary outworking of sovereign regeneration. The will is not invited to respond, but is transformed as an effect of unilateral divine choice.

The relational–ontological model presented here offers a clarified and covenantally coherent alternative. Prevenient grace is not ambient or merely enabling; it is defined as a divinely initiated epideictic confrontation with ontologically instantiated truth. It is not resistible prior to confrontation, nor is it coercive upon arrival—it unveils truth, confronts the soul with moral clarity, and initiates the elentic threshold, where the subconscious noetic posture is exposed and the volition summoned.

At this point, the Deontic–Modal Unit (DM Unit)—always suboperative—is no longer ignored or suppressed. Its claims are epideictically unmasked, and the person stands volitionally accountable—not abstractly, but ontologically and relationally, in full moral awareness.

This moment marks not a mechanical activation, but a categorical shift: from suppressed ignorance to exposed obligation; from passive orientation to moral summons. It is the moment between confrontation and decision, where the soul either resists or yields.

Sanctifying grace, within this framework, begins only after volitional consent is given and the soul aligns with disclosed moral truth. It is the transformative grace by which the will—now covenantally bound—is gradually conformed to God’s moral nature. It does not override the will, but works through it—honoring the surrender and sustaining the soul’s trajectory of moral restoration.

This sequential clarification:

Preserves covenantal logic;

Ensures that transformation never bypasses volition;

Safeguards the procedural coherence of divine judgment.

Grace remains truly grace: unmerited, relationally initiated, and non-coercive—but also morally binding when it discloses truth, evokes elentic recognition, and calls the soul to yield.

In the relational–ontological model, divine confrontation is universal, though not uniformly doctrinal. Some are confronted explicitly—through Scripture, gospel proclamation, or theological engagement. Others are confronted implicitly—through conscience, moral crisis, or the embodied witness of kingdom ethics (cf. Matthew 25:40; Romans 2:14–16). These are the “Christian Unawares”—souls who respond to divine presence without formal religious categories.

The decisive factor is not the medium of instruction, but the ontological reality of truth confronting the will: a moral summons epideictically initiated, not merely taught or inferred. Whether through text, trial, or testimony, the soul is brought to the elentic threshold—confronted not with abstract propositions, but with truth instantiated and volitionally aimed. The demand is not cognitive assent, but relational surrender.

In this way, divine justice remains impartial: it does not judge by informational access or doctrinal precision, but by the volitional posture the soul assumes when truth is disclosed.

The Deontic–Modal Unit, always latent as a sub-operative faculty of moral response, is not newly activated in these moments—but epideictically unmasked and morally re-centered. What had been suppressed or misaligned is now brought to ontological clarity. The soul, no longer buffered by ambiguity, stands volitionally accountable.

Judgment, then, is not procedural or propositional, but ontological and relational—rendered not by what one knows, but by how one responds when truth appears. Whether through conscience, suffering, Scripture, or embodied witness, the confrontation is real—and the elentic exposure of the subconscious noetic posture clarifies the only two moral options: alignment or resistance.

See Deontic Modal Unit for further discussion.

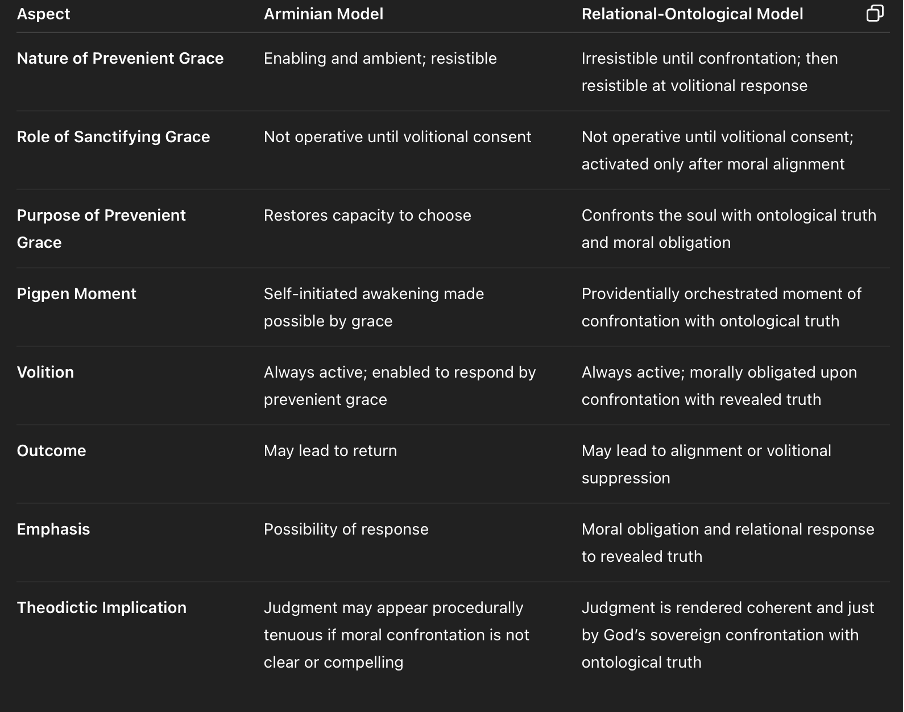

The following comparative grid summarizes the key distinctions outlined above and underscores the logical consequences of each position on grace, volition, and judgment.

The repeated declaration in Exodus that “God hardened Pharaoh’s heart” has long posed a theological challenge—especially for models that seek to uphold both divine righteousness and human moral accountability. Within the relational-ontological framework, this event is not viewed as an instance of divine coercion or arbitrary reprobation, but as a paradigm of:

Divine confrontation;

Volitional exposure; and,

Judicial hardening

…all occurring within the layered structure of God’s providence and moral prerogative.

Author’s Note on Terminology:

Several of the terms used in this appendix—such as antecedent and consequent will or the layered types of providence—originate in classical theological discourse, particularly within post-Reformation Arminian and Wesleyan traditions. However, within this project, such terms are recontextualized to articulate the moral-relational architecture of divine self-disclosure and judgment. They are employed not to reaffirm traditional systems, but to illuminate the ontological logic of how God confronts, exposes, and judges the will in a way that preserves both sovereignty and creaturely accountability.

Pharaoh was created under creative providence—formed with purpose and endowed with moral agency, like all human souls. This was followed by sustaining providence, which continually upholds creation. God’s antecedent will for Pharaoh, as for all persons, was that he should not perish (cf. Ezek. 18:23), and specifically, that he would acknowledge God’s authority and release Israel. Pharaoh was not created as a reprobate, but as a responsible agent situated within a covenantal narrative.

Yet governing providence superintends the outcome of human decisions in alignment with God's redemptive intent (Lam. 3:37). This expresses God’s consequent will, in which Pharaoh’s role—whether in submission or rebellion—is incorporated into the divine plan. This is not determinism, but the sovereign orchestration of morally contingent realities toward an ultimate good.

Pharaoh’s rebellion emerges from his own volitional agency—a freely chosen trajectory of suppression. By permissive will, God allows this path to unfold. Through concurrent providence, He sustains and cooperates with human action without becoming its moral author. God remains the effector of circumstances (plagues, signs, delays, confrontations), yet never the cause of sin.

This divine cooperation is not tacit approval but a form of restrained governance—directing events without overriding agency. Pharaoh’s will is not overruled; it is revealed.

To say “God hardened Pharaoh’s heart” does not imply compulsion. It discloses God's foreknowledge of upcoming judicial consequences: as Pharaoh repeatedly resists, God intensifies confrontation, withdrawing restraint and escalating exposure. This makes the moral summons inescapable—not through force, but through relational insistence.

This aligns with the pattern of Romans 1:24–28, where God “gives them over” to their wilful volitional suppression. In this model, hardening is not divine causation of rebellion but divine judicial amplification of what has been relationally disclosed. God confronts; the soul either yields or suppresses. When suppression continues, confrontation intensifies—thereby crystallizing the soul’s posture and sealing its trajectory.

Hardening, then, is not God disabling Pharaoh’s will, but exposing it—through escalating truth-confrontation. The more the light intensifies, the more the posture is revealed. This discloses a foundational principle: every moral choice invites divine response—either deepening grace or intensifying judgment.

This framework acknowledges a vital distinction often overlooked in deterministic theologies: the difference between God’s antecedent will and His consequent will.

God’s antecedent will reflects His benevolent desire that all should be saved, act justly, and walk in the truth (cf. Ezek. 18:23; 33:11; 1 Tim. 2:4; 2 Pet. 3:9). It is the will of God in creation, covenant, and calling—a will grounded in love, not decree.

God’s consequent will, by contrast, is what He justly permits in light of creaturely response. It takes into account the actual posture of the will, the response to revelation, and the persistence or repentance of the moral agent. This is not passive resignation but sovereign orchestration—God allowing the outcomes of free moral agency while integrating them into His redemptive governance (cf. Lam. 3:37–38; Rom. 9:17–22).

Pharaoh’s case illustrates the distinction between God’s antecedent and consequent will. God’s antecedent will was that Pharaoh would humble himself and release Israel. This was not a manipulative design, but a genuine moral invitation—a summons to alignment and obedience. But Pharaoh’s repeated suppression and rebellion shifted the relational context: from invitation to exposure, from opportunity for salvific blessing to occasion for judgment. The resultant hardening was not a predetermined override, but a relational outcome—God’s consequent will responding to what Pharaoh’s will had already chosen. In this model, hardening is not coercion but confrontation intensified—the moral revelation of a volitional trajectory already fixed by defiance.

This distinction not only safeguards God's moral integrity—it also enhances His sovereignty. For true sovereignty is not the manipulation of predetermined outcomes, but the wisdom to govern freely chosen moral trajectories without compromising human agency, divine justice or love. God’s consequent will demonstrates and exposes a deeper form of sovereignty: one that confronts, responds to, and integrates human agency into the arc of redemptive history without nullifying freedom or moral responsibility. It is precisely because God does not need to override the will that His rule is more majestic, more patient, and more righteous than systems of coercive determinism allow.

This twofold will also preserves the moral consistency of God’s character. He does not will sin, but He permits it. He does not coerce evil, but He confronts it. He does not bypass moral agency, but He governs through it. In this way, divine justice is not abstract or mechanical—it is relational, responsive, and morally proportionate, rooted in the revealed posture of the soul rather than imposed by decree.

God’s statement that He raised up Pharaoh (Ex. 9:16; Rom. 9:17) and the concept of a “vessel of destruction” (Rom. 9:22) are often read as indicators of predestined reprobation. However, in this framework, taking into account the gradualness and fullness of scriptural revelation, these are understood relationally: God created Pharaoh, knowing all possible outcomes (omniscience), and allowed Pharaoh’s chosen resistance to reach maturity under divine pressure (judicial exposure). Thus:

In this sense, God “takes responsibility” for Pharaoh’s role in redemptive history—not as the author of rebellion, but as the one who permitted it, enabled it (via concurrent providence), and judged it without compromising His benevolence or ultimate purposes (consequent will), nor Pharaoh’s moral agency and accountability.

A common hermeneutical failure in discussions of Pharaoh, election, or judgment is the tendency to draw theological conclusions from isolated texts rather than interpreting them within the full and entire narrative structure of biblical revelation. God’s dealings with Pharaoh—like all divine judgment—unfold within a relational sequence of truth, confrontation, volitional response, and moral exposure. The broader biblical witness—including Dan 7, Rom 1, Eze 18, Matt 24–25, 2 Thess 2:10–12, and Rev 20—affirms a coherent divine justice program, not a deterministic decree. The relational-ontological model emphasizes that God's righteousness is discerned across the canonical arc, not in isolated proof texts or extracted fragments. Where some traditions treat Exodus or Romans 9 as doctrinal endpoints, this model treats them as relational disclosures, intended to be read in light of God’s consistent and complete scriptural self-revelation as just, confrontational, and covenantally faithful.

This model preserves the coherence of divine justice, the freedom of the creature, and the integrity of providence:

Pharaoh’s story illustrates how grace confronts, how the will resists, and how judgment follows not from decree, but from the relationally revealed state of the soul. In this, Pharaoh becomes not a scapegoat of divine fiat, but a mirror held up to the soul: to resist light is to incur judgment, not because one is predetermined, but because truth refused becomes the agent of its own exposure.

This section evaluates competing systems that threaten or distort relational justice—including Calvinism (section III.1) and Adventism (section III.2)—not to attack, but to clarify.

The doctrine of double predestination, associated with classical Calvinism, asserts that God eternally and unconditionally elects some individuals to salvation and others to reprobation—apart from foreseen faith or volitional response. While historically intended to uphold God’s sovereignty, this doctrine raises substantial theological tensions when placed alongside Scripture’s consistent witness to divine judgment, moral agency, and relational accountability.

The relational-ontological framework approaches this topic not to dispute for its own sake, but to evaluate how well such a view aligns with the biblical pattern of divine confrontation, human response, and covenantal judgment. A God who confronts souls with ontological truth, records their responses, including the moral posture of the soul under confrontation, and judges in light of those revealed postures offers a more coherent account of justice and grace than one based on fixed decree alone.

The biblical testimony affirms that God evaluates creatures based on their deeds—not arbitrarily, but relationally. This process assumes genuine response, volitional capacity, and moral exposure.

These verses point to a real-time evaluation, not a retrospective confirmation of a prior eternal decree—but a judgment based on observable conduct and relational posture. In a relational model, judgment reflects interaction, not imposition.

Throughout Scripture, divine judgment is tied to the recording and remembrance of moral deeds. This imagery suggests investigation and accountability—not predetermination.

If destinies were fixed apart from moral conduct, the recording of deeds would lose theological meaning. But the consistent he emphasis on record-keeping and divine remembrance affirms not merely forensic accountability, but relational exposure—truth confronting the will and bearing witness to its revealed posture.

The eschatological vision of Revelation reinforces this principle: verdicts follow volitional history—that is, the unfolding trajectory of the will under divine confrontation and grace. If destinies were fixed apart from moral conduct, the recording of deeds would lose theological meaning. But the consistent emphasis on record-keeping and divine remembrance affirms not merely forensic accountability, but relational exposure—truth confronting the will and bearing witness to its revealed posture.

This culminates in the solemn declaration of Revelation 22:11:

“He that is unjust, let him be unjust still… and he that is righteous, let him be righteous still.”

This is not fatalism—it is finality. At the close of redemptive history, the moral record does not just inform judgment; it discloses what the soul has become. Truth, once invited and resisted, becomes sealing; if embraced and internalized, becomes salvific.

Salvation is never earned—but neither is it imposed without consent. Scripture affirms that the righteous are cleared, not created righteous by fiat.

Hebrews 12:23 –“To the general assembly and church of the firstborn, which are written in heaven, and to God the Judge of all, and to the spirits of just men made perfect."

Luke 21:36 –“Watch ye therefore, and pray always, that ye may be accounted worthy to escape all these things that shall come to pass, and to stand before the Son of man.”

This worthiness is not self-derived, but neither is it an imposed status. It is relationally assigned—the fruit of gradual ontological alignment and yielded posture not the product of works nor the result of arbitrary decree.

When double predestination is placed under relational and moral scrutiny, several key tensions emerge:

These tensions suggest that double predestination functions more as a metaphysical assertion than a relational or moral reality.

This model offers a restorative framework in which:

Justification is dynamic and covenantal—initiated by grace, sustained by relational fidelity, and always vulnerable to volitional rejection. Apostasy is not a failure of grace, but a revelation of sustained moral resistance. This is exemplified in the fall of Demas (2 Timothy 4:10), the rejection of Saul (1 Samuel 15:23), the corruption of Balaam (2 Peter 2:15), and the sober warning of wilful sin after receiving truth (Hebrews 10:26–29).

Scriptural Reinforcement of Moral Vigilance—The call to guard the will's responsiveness is echoed in Ecclesiastes 12:1: “Remember now thy Creator in the days of thy youth…” This is not mere nostalgia—it is an exhortation to establish early moral orientation, because the trajectory of the heart will later crystallize. This aligns with the broader biblical principle of guarding the inner life. Pro 4:23 – “Keep thy heart with all diligence; for out of it are the issues of life.” Ecc 11:9 – “...walk in the ways of thine heart, and in the sight of thine eyes: but know thou, that for all these things God will bring thee into judgment.” Matt 6:22–23 – “The light of the body is the eye… if therefore thine eye be evil, thy whole body shall be full of darkness.” Philip 4:8 – “Whatsoever things are pure… think on these things.”

These passages affirm the importance of disciplining the intake and meditations of the heart, as both reflective and determinative of ontological alignment.

While the intent behind double predestination may be to preserve divine sovereignty, it does so at the cost of relational justice, volitional integrity, and biblical judgment theology. A relational-ontological account retains God’s initiative and rule, while upholding moral gravity, scriptural coherence, and the true meaning of grace and judgment.

“The Lord is known by the judgment He executes.” (Psalm 9:16)

Before Eden: Divine Pedagogy in the Angelic Fall. See the standalone footnote for a full discussion of the angelic rebellion, the epidectic–elenctic arc, and its pedagogical bearing on human judgment.

While the relational-ontological model is not derived from Adventist theology, it does share several important convictions—particularly regarding volitional accountability, covenantal responsibility, and the integrity of divine judgment. However, there are also significant refinements and structural differences that distinguish this model, especially in its formal articulation of grace, conscience, and relational confrontation. This section outlines those points of convergence, enhancement, and divergence. These clarifications are offered not to replace Adventist theology but to expand the philosophical clarity of shared convictions.

The following foundational convictions are held in common between the relational-ontological framework and historic Adventist theology (particularly as reflected in the writings of Ellen White and post-Reformation Adventist systematic thought):

While congruent in many areas, the relational model deepens and formalizes certain Adventist insights in ways that are structurally and philosophically clarified:

Several important distinctions separate the relational-ontological model from conventional Adventist systematic categories:

Together, these divergences underscore that while the relational-ontological framework honors the moral insights within Adventism, it systematizes them at the ontological and semiotic levels, offering broader coherence without dependence on denominational categories or inherited systematic constraints.

The relational-ontological model, while rooted in covenant theology, has consequences far beyond intra-Christian soteriology. It exposes the ontological impossibility of religious neutrality and exposes the philosophical incoherence of syncretism—the attempt to blend divergent religious systems into a unified or tolerant whole. If theology misfires by ignoring volition, justice, and covenant: philosophy misfires by assuming neutrality, equivalence, or cultural relativism in matters of worship.

Syncretism is often defended on cultural or moral grounds: a conciliatory gesture of inclusion, humility, or peace. But under a relational ontology of truth, worship is not a neutral act—it is an ontological alignment with a being, a moral order, and a revelatory claim. As such, worship is never merely cultural or symbolic; it is covenantal. To participate in rituals directed to referents or beings not ontologically revealed by the One True God is not merely mistaken but a form of ontological misalignment (cf. 1 Corinthians 10:20, Deuteronomy 32:17).

Thus, syncretism does not represent humility, but category confusion. It treats incompatible referents as if they were metaphysically exchangeable. This is not only theologically false but logically incoherent, violating both the law of non-contradiction and the moral logic of allegiance.

Modern theology often assumes that religious sincerity or shared ethical aspiration renders all systems functionally equivalent. But sincerity cannot transmute falsehood into truth. Paul does not reduce non-covenantal worship to mere ignorance; he locates it in communion with ontologically counterfeit referents—spiritual realities or projected constructs that rival divine authority. He affirms that such sacrifices, however devout, represent misdirected spiritual allegiance (1 Cor 10:20). This is not rhetorical hyperbole, but an ontological verdict: where the One True God is not acknowledged, another will be enthroned—whether a concept, a spirit, or a projection.

Within this framework, no religious system is spiritually neutral. All worship either aligns with revealed truth or enters into communion with a counterfeit. The “grey zone” presumed by pluralism is a conceptual illusion.

Even atheism, often presented as a non-position or rational default, functions typologically as a misdirected allegiance—denying ontological truth by constructing a counter-framework of meaning and moral grounding. The relational-ontological model exposes this as not a posture of neutrality, but an implicit rejection of relational confrontation. Like all religious alternatives, it reflects an allegiance—only this one is framed as unbelief. Atheism is veiled allegiance.

Biblical worship is exclusive not because of tribalism, but because of ontology. The self-revealing nature of the One True God creates a binary pressure: either one responds to divine relational summons (prevenient grace and moral confrontation), or one remains in a misaligned system—however dignified, ancient, or aesthetically beautiful.

Thus, the rejection of pluralism and syncretism is not a sectarian claim but the logical entailment of a worldview in which:

To attempt to blend worship of the One True God with systems that reference ontologically invalid or non-instantiated beings—whether ancient mythologies, modern spiritualities, or hybrid philosophies—is not inclusive. It is a breach of ontological coherence and a rejection of revealed relational order.

In the relational-ontological framework, worship is not culturally symbolic but covenantally real. Every act of devotion or rejection represents ontological alignment—either with the One True God or with an alternative, however implicit. Syncretism is not merely theological confusion, but ontological misalignment—a fusion of mutually exclusive referents resulting in covenantal breach; pluralism is not open-minded neutrality but ontological incoherence. Whether through ritual, ideology, or negation, every soul is engaged in a relational moral trajectory. There is no neutral ground: to worship truly is to respond rightly to divine self-disclosure; to evade or conflate is, in effect, to enthrone a substitute. In this way, truth, worship, and judgment converge, and the myth of religious neutrality is decisively collapsed.

Footnote

^Before Eden: Divine Pedagogy in the Angelic Fall.

Before the human drama began, a rebellion erupted among non-corporeal moral agents in heaven (Rev 12:7-9). A rational being sowed distrust in divine authority through persuasion and misrepresentation rather than brute force (John 8:44; Isa 14:12-14; Ezek 28:12-17). Chosen from a platform of perfect clarity, that first act demonstrated that free allegiance can be withdrawn even in a sinless realm.

Instead of extinguishing the revolt, God allowed it to ferment until one-third of the host committed themselves and were expelled (Rev 12:4; 2 Pet 2:4). This restraint inaugurated an epidectic–elenctic theodical arc—a display-and-exposure process in which God’s character is publicly vindicated (epidectic) while rebellion’s self-destructive logic is allowed to reveal itself (elenctic). The same principle governs human history, though with an essential adjustment: humanity now sins from an impaired platform (Rom 5:12). To preserve moral significance, God interposes remedial light and grace—law, prophets, incarnation, Spirit—so that every person encounters sufficient revelation to disclose an informed posture (John 1:9; 3:19-21).

This angelic phase framed Earth’s probationary theatre: angels witnessed creation (Job 38:7) and continue observing redemption’s unfolding wisdom (1 Cor 4:9; Eph 3:10). Scripture is silent on whether fallen angels can ever reverse allegiance (cf. Heb 2:16); that uncertainty does not alter the arc itself but simply marks another boundary of revelatory restraint.

Those familiar with The Great Controversy (EG White) will recognise this pre-Adamic stage as the opening act in the cosmic conflict—a standing exhibit of God’s resolve to reveal rather than coerce moral allegiance. Angelic ontology therefore remains largely undisclosed and peripheral to the human covenantal narrative, yet their rebellion endures as the primordial witness to divine pedagogy. For readers unfamiliar with the origins of the Great Controversy theme, see Spiritual Gifts, Vol. 1 (1858), available for download here

.

A reference guide to the theological-ontological terminology used throughout this section

Antecedent Will God’s original, benevolent intention for creation and each creature. It reflects His desire for righteousness, repentance, and relational harmony. E.g., God wills that none should perish (2 Pet. 3:9).

Consequent Will God’s responsive will, accounting for human free agency. It incorporates the creature’s choices—whether of obedience or rebellion—into His sovereign plan without negating freedom. E.g., Pharaoh’s rebellion integrated into Israel’s deliverance.

Reactive or Judicial Will God’s volitional response to persistent suppression of truth. It includes handing people over to their desires (Rom. 1:24), confirming hardness of heart, or intensifying delusion as a consequence of moral resistance.

Creative Providence God’s act of bringing all things into existence, including persons with moral agency and potentiality. It implies God’s foreknowledge of the creature’s possible paths without determining them.

Sustaining Providence God’s ongoing upholding of the created order, ensuring the persistence of being and order, even amidst rebellion.

Permissive Providence God allows creaturely will to act freely, even in sin. This permission is never passive—God is not a spectator—but is part of His wise governance and moral restraint.

Concurrent Providence God cooperates with the creature’s choices—empowering actions, sustaining outcomes—without endorsing sin. He is the effector of events, but not the author of rebellion.

Governmental Providence God governs all things toward His purposes. It includes the orchestration of free choices—righteous or rebellious—into a coherent plan of redemption and justice.

Judicial Providence God acts righteously in response to sin, including the intensification of delusion, the hardening of the will, or removal of restraint. It is not punitive decree, but righteous exposure of the soul’s chosen trajectory.

Grace is not a monolithic substance or sentiment but a structured, covenantal sequence of divine action within a moral universe. In this framework, grace functions in multiple distinct phases, each morally and ontologically ordered.

Prevenient Grace

The initiating grace by which God confronts the soul with ontologically real truth. It is not merely ambient or enabling, as in classical Arminianism, but constitutes an irreversible moral summons up to the point of volitional response. Once the confrontation occurs, the person must either align with revealed truth or suppress it. This confrontation activates the DM Unit and renders the person morally accountable.

Sanctifying Grace

The transformative grace that begins only after volitional consent is given. It is not merely ethical improvement but the relationally driven reconstitution of the will into alignment with God’s moral order. It follows prevenient grace but does not precede it. Unlike Calvinist regeneration, it does not bypass the will. Unlike Arminian treatments, it is not a generalized post-conversion atmosphere, but a covenantal force contingent on consent.

Judicial Grace

A grace extended even in restraint or delay—when judgment is withheld to allow volitional response. It reflects God's patience and long-suffering, especially prior to full confrontation. While not transformative, it is preservative and consistent with God's moral character.

Common Grace

In Reformed theology, common grace refers to God's general benevolence toward all humanity (e.g., rain, societal order). This framework does not dispute such mercy, but reframes it as providential restraint rather than a grace that prepares the will for salvation.