In this section, we examine the moral consequences of regeneration—not merely as an event, but as an ongoing realignment of the whole person to divine reality. Having explored the internal structure of conscience and the volitional threshold of response, we now turn to the lived implications of that response: the transformation of posture, perception, and embodiment. This is not a further development of the DM unit itself (alluded to in the Moral Taxonomy section), but the ontological and phenomenological alignment that unfolds as the will entrains to sanctifying grace. Moral structure becomes moral rhythm; conscience becomes character.

Contemporary moral psychology and philosophical ethics often acknowledge the inner conflict of conscience. Thinkers such as Freud (superego and guilt), Nietzsche (ressentiment and slave morality), and Charles Taylor (the moral sources of the modern self) all attempt to explain this moral tension. Yet despite their insights, these accounts lack a transcendent referent.

For Freud, conscience is pathology—an internalization of social constraints.

For Nietzsche, it is self-deception—an expression of weakness and resentment.

For Taylor, it is expressive tension—a byproduct of competing moral sources in a secular age.

These models may exhibit psychological plausibility, but they are metaphysically non-compulsory. Their internal coherence does not entail moral obligation.They describe experience, but cannot ground it. The conscience becomes either evolutionary residue or cultural reflex—never covenantal encounter.

By contrast, the biblical framework treats conscience not as a psychological remnant, but as an ontological echo of divine law—a site where grace confronts the fallen self with moral reality. What secular models merely interpret, Scripture grounds: the inner war is not simply psychological, but covenantal, ethical, and relational.

Before delving into the Deontic-Modal (DM) unit, as previewed in the Moral Taxonomy section, it is important to recognize that the structure we propose—while distinct—bears resemblance to established cognitive frameworks such as Kant’s a priori categories, Chomsky’s universal grammar, and Piaget’s schema theory. These secular models all assume that human cognition operates within pre-configured structures that shape how we perceive, categorize, and interpret experience. Piaget’s schemata, for instance, can be seen as ontological scaffolds populated through interaction with the world—frameworks for interpreting meaning that are tacitly acquired and recursively adapted. But while these models capture something of the structural readiness of the human mind, they typically flatten or secularize the deeper moral architecture that underlies such readiness.

By contrast, the Deontic–Modal unit is not a mere formal template or cognitive instinct. It is a morally charged, ontologically grounded framework, embedded within the phenomenological space of the person. It does not simply help interpret data—it confronts the soul with moral responsibility.

It does not diagnose, it summons.

It does not override the will, it addresses it.

It does not categorize reality, it calls for alignment with reality as defined by God.

Unlike Piaget’s schema or Haidt’s intuitionism, the Deontic-Modal (DM) unit is not merely biologically encoded or culturally conditioned—it is, suboperative: universallypresent, morally active, and awaiting full resonance through covenantal surrender. It is not universal grammar, but a universal internal-conscience confrontation—an internal covenantal structure echoing God’s revealed will, summoning the soul to fidelity.

Secular models describe the shape of cognition; the DM unit discloses the weight of conviction. It does not override freedom, but summons the will to align with moral reality. This resonance is not learned from culture or abstracted by deduction—it is relationally awakened. The assent to align—whether through repentance, obedience, or resistance—is not automatic, but volitional.

In this way, moral clarity is offered, not imposed. Where the offer is received, the entire phenomenological space becomes gradually suffused with ethical coherence—internally in the conscience, externally in praxis—enabling moral discernment across all domains of life.

The DM unit is ontologically installed and morally operative even in the unregenerate, yet it seldom governs the whole of life. Most people answer its summons selectively, suppressing some demands while conforming to others—an issue of uneven submission, not functional absence. Consequently, the unregenerate moral experience is marked less by blankness than by conflict. As Paul observes, “the work of the law is written in their hearts, their conscience also bearing witness, and their thoughts accusing or else excusing one another” (Rom 2:15). This is no mere social reflex; it is conscience as ontological resonance—the internal reverberation of the Deontic-Modal imprint placed in God’s image-bearers, morally structured, covenantally designed, and phenomenologically alive to divine order.

Full relational awakening occurs when divine confrontation presses the entire moral field into view, calling not for incremental improvement but wholehearted surrender (Gal 5:24). Should a soul persist in shielding regions of darkness, God may ratify that posture by “giving them over” to the path they insist upon (Rom 1:24; 2 Thess 2:10-12). Such judicial withdrawal does not abandon justice; it honours creaturely agency by allowing the chosen trajectory to unfold.

To avoid ambiguity, we now refer more precisely to the DM structure as the internal imprint of obligation and modality—always present but variably heeded—and the axiological horizon as the divine value-reality that interprets, awakens, and aligns that imprint. Without alignment to this revealed horizon, the DM structure may still function, but it will be misdirected—co-opted by counterfeit goods or reduced to effigiated virtue. True moral activation requires not only the presence of moral architecture, but its resonance with God's axiological order. From this realignment emerges moral praxis—not as reactive behavior or imposed compliance, but as relational fidelity. In this view, praxis is the exempliation of rightly ordered values through the freedom of the regenerate will, responding to the divine moral order with personal and volitional alignment.

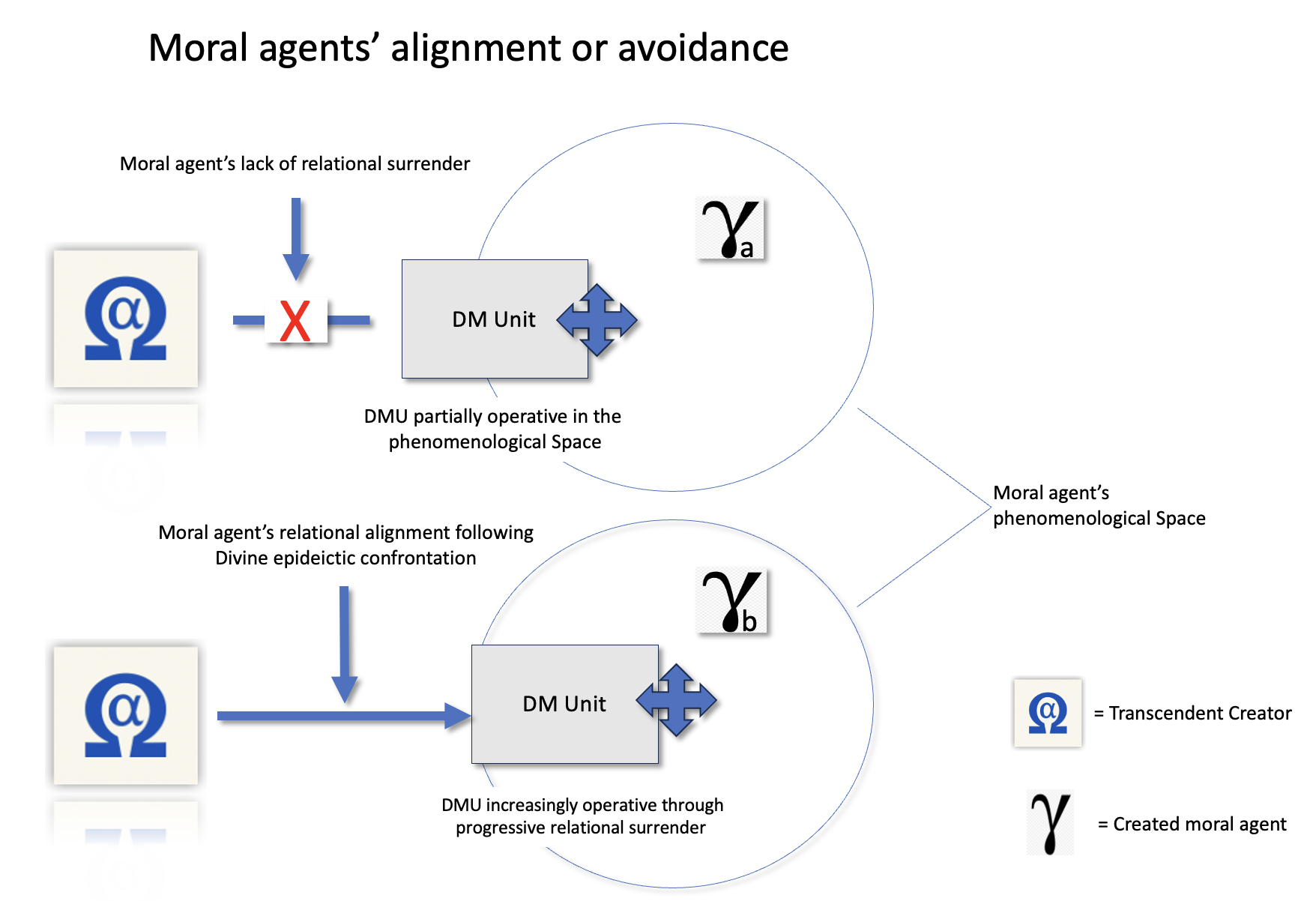

The slide below depicts alignment or avoidance as discussed.

In this framework, divine confrontation is not manipulative, but revelatory. Modern notions of “provocation” often suggest coercion—stimulating response by overriding reason, emotion, or will. But God does not provoke rebellion; He reveals noetic disposition. His confrontation of the soul is diagnostic, not deterministic: it exposes what already resides within, without altering or compelling it. The agent’s response does not disclose divine causation but human posture. This form of revelatory unveiling—epideixis—preserves moral agency while vindicating divine justice.

This understanding of confrontation positions the model over and against the two dominant theological paradigms:

Unlike Calvinism, it rejects the notion of irresistible grace that overrides the will through unilateral election.

Unlike Arminianism, it does not reduce grace to a passive or universally available offer awaiting human initiative.

Instead, prevenient grace is understood as sovereign epideictic confrontation—a morally charged unveiling that confronts each soul at least once^ in their lifetime with the weight of divine truth. This is the “swine trough” moment (Luke 15:16–17), where the illusion of autonomy collapses—an end of self under the pressure of moral reality.

This confrontation intensifies the resonance of the inscribed DM unit, summoning the moral agent to reckon with the full extent of their immediate accountability—not compartmentalized or deferred, but brought to ontological clarity in the light of divine truth. The soul is not merely given options, but summoned into a moment of ontological exposure.

This epideictic unveiling of truth initiates an elentic moment—not in the classical rhetorical sense of external refutation, but as the internal exposure of noetic posture. The soul is revealed to itself in relation to divine goodness, and the contradiction (or confirmation) becomes undeniable. The will must now respond—not merely to a proposition, but to what has been shown. The will is neither bypassed nor coerced—it is called to choose in the light of unveiled reality.

This is not determinism. The response remains volitional, conditioned by the soul’s noetic posture. Yet the awakening is ensured: the confrontation is divinely initiated, not self-generated. God retains the prerogative to summon each soul to reckon with truth—not by psychological manipulation, but by moral epiphany (Joshua 24:15). This summons is not abstract invitation but a decisive confrontation, as when Joshua declared, “Choose you this day whom ye will serve.” The will is not overruled but awakened, and the agent stands before a revealed horizon that demands moral response.

The conscience, thus stirred, does not act in abstraction, but as the interface of relational reality. The soul sees not only what is right, but what it has become. God seeks covenantal assent, not mechanical compliance. Yet He does not abandon His initiative in the drama of redemption. In confronting every soul with unveiled truth, God both honors moral freedom and vindicates His justice.

This is the epideictic work of grace: the prodigal recalls not merely bread, but belonging—ordered goodness from which he has fallen. The prodigal does not merely recall bread, but belonging; not just provision, but the ordered goodness from which he has fallen. This recollection is not emotionally conjured but ontologically catalyzed—a confrontation with relational reality that shatters illusion and initiates repentance.

This is epideixis: a revelatory unveiling in which the soul is confronted not simply with past choices, but with the beauty, coherence, and moral structure it has rejected. It is here that the Moral Causation Hierarchy—Axiology → Deontology → Modality → Praxis—is not reactivated as if absent, but pressed into conscious alignment. What had been suppressed is now made clear: not abstractly, but personally.

Axiology re-emerges as the memory of divine goodness.

Deontology reasserts itself as the soul perceives its true relational obligation.

Modality becomes intelligible as the will glimpses what must now be chosen or forsaken.

Praxis is no longer neutral—it becomes morally decisive: not merely action, but turning.

In this epideictic moment, the conscience is not bypassed but reoriented. The soul is no longer buffered by ignorance or moral haze—it stands before unveiled truth. The confrontation does not offer options; it imposes clarity. And that clarity initiates the elentic threshold: the inward unveiling of the noetic posture.

The result is not behavioral adjustment, but relational crisis—a call to repentance born of unveiled contrast. The elentic response does not emerge from mere introspection, but from the moral shock of divine goodness revealed. It is here, at this inner unveiling, that the will must act—to yield in contrition or suppress in self-preservation.

The DM unit is ontologically installed and morally operative even in the unregenerate, yet it seldom governs the whole of life. Most people answer its summons selectively, suppressing some demands while conforming to others—an issue of uneven submission, not functional absence. Consequently, the unregenerate moral experience is marked less by blankness than by conflict. As Paul observes, “the work of the law is written in their hearts, their conscience also bearing witness, and their thoughts accusing or else excusing one another” (Rom 2:15). This is no mere social reflex; it is conscience as ontological resonance—the internal reverberation of the Deontic-Modal imprint placed in God’s image-bearers, morally structured, covenantally designed, and phenomenologically alive to divine order.

Full relational awakening occurs when divine confrontation presses the entire moral field into view, calling not for incremental improvement but wholehearted surrender (Gal 5:24). Should a soul persist in shielding regions of darkness, God may ratify that posture by “giving them over” to the path they insist upon (Rom 1:24; 2 Thess 2:10-12). Such judicial withdrawal does not abandon justice; it honours creaturely agency by allowing the chosen trajectory to unfold.

Christianity has long been described—especially in the Wesleyan tradition—as an experimental religion: one in which spiritual truths are not merely believed, but tested, proven, and embodied. This framework affirms that emphasis while grounding it more deeply in ontological reality. The DM unit provides the moral architecture by which God confronts the soul—not through abstract doctrines, but through relationally charged choice sets.

Under sanctifying grace, these choices test whether the regenerate heart truly loves and obeys God. As Christ said, “If ye love me, keep my commandments” (John 14:15). Such moral testing is not incidental; it is essential to theodicy. God’s justice is vindicated not in theory, but in the soul’s real-time response. Regeneration is not confirmed by profession alone, but by volitional fidelity.

Even where the DM unit is not fully awakened, its ontological presence persists. Disuse is not innocence. The soul remains morally confronted by glimpses of duty and traces of divine goodness, which it may sidestep without outright rejection. But evasion itself reveals posture. Resistance may appear not as rebellion but as deferral, compartmentalization, or passive disregard—yet all such responses are morally charged. “This is the condemnation,” said Jesus, “that light is come into the world, and men loved darkness rather than light... for everyone that doeth evil hateth the light... lest his deeds should be reproved” (John 3:19–20).

Thus, the DM unit deepens the experimental nature of faith: not only is truth revealed and grace offered, but the soul is held accountable for how it responds—whether in fidelity or in evasion.

What, then, of those who have never encountered formal gospel proclamation or ecclesial instruction? Christ anticipates this concern in the parable of the sheep and goats (Matt. 25:31–46), where some are welcomed into the kingdom without knowing they had served Him: “Lord, when saw we thee…?” (v. 37). These are the “Christian-unawares”—those whose moral response to divine confrontation was real, though they lacked explicit theological categories. Their deeds revealed covenantal posture. This affirms that God’s prevenient grace is not limited to ecclesial exposure, but reaches every soul through conscience, crisis, or hidden hospitality (cf. Rom. 2:14–16). What matters is not institutional affiliation, but volitional response to God’s moral will as it epideictically confronts the soul demanding an elentic response that either aligns with truth or evades it. Dogma, doctrine, catechesis culture, are all irrelevant: but as duty embedded and choice presented is paramount.

In this light, the universally present DM unit functions as the lowest common denominator of moral accountability. It is universal, ontologically impartial, and morally responsive. Thus, divine judgment is not arbitrary or elitist; it is grounded in universal moral confrontation, proportionate to the truth encountered and the conscience stirred. This preserves the coherence of a universal divine theodicy: every soul will have been summoned to choose, regardless of material circumstances.

Notwithstanding the universality affirmed in section II.F., it must be stated: those who have received the explicit testimony of Christ—through Scripture, doctrine, or participation in the visible church—will not be judged by moral fidelity alone, but by their volitional response to the fuller revelation entrusted to them. 'To whom much is given, much shall be required,' (Luke 12:48). The same DM unit is active, but the field of moral accountability expands proportionally with the degree of light received and the covenantal claims professed.

Formal believers, then, are assessed not only by their adherence to moral duty, but by their faithfulness to revealed doctrine and ecclesial stewardship. This is exemplified in Christ’s warning: “Whosoever shall deny me before men, him will I also deny before my Father” (Matt. 10:33). Such denial is not doctrinal ignorance—it is moral collapse at the moment of relational exposure. Even doctrinal fidelity, when rightly understood, is a moral act: to confess Christ under trial is not mere orthodoxy, but covenantal allegiance.

In sum, the Deontic–Modal Unit is not a speculative faculty, but a covenantal mirror—revealing the soul’s moral trajectory in response to divine grace. It does not merely register ethical awareness; it discloses allegiance. Across a lifetime—through every encounter, choice set, and volitional act—the soul’s noetic disposition is both formed and unveiled. This is the basis upon which divine judgment is rendered—not as arbitrary decree, but as the relational consequence of how revealed truth has been received or resisted.

This unveiling unfolds along what may be called the epideictic–elentic axis:

Epideictic confrontation initiates the moment of divine disclosure—where goodness, duty, and possibility are brought into view.

Elentic exposure follows, marking the internal self-revelation of the soul’s moral posture in response to what has been shown.

The DM Unit mediates this axis: it receives divine confrontation, translates it into moral resonance, and issues a volitional summons. It is not a neutral processor of input, but a morally attuned architecture—structurally calibrated to divine order and relationally responsive to ontological presence.

An elentic response is not optional—it is demanded by unveiled truth. Once the soul is confronted by ontological reality, neutrality collapses. The will must respond—not to abstraction, but to a revealed moral horizon that now defines the terms of relational existence.

To love the truth is to align with the One who is Truth; to suppress it is to declare ontological independence from the only source of moral coherence. In this light, the DM Unit is not merely a faculty of moral perception—it is an instrument of divine discernment. It does not merely assess behavior; it reveals whether the soul stands in fidelity or defiance.

Note on Diagnostic Alignment: The Deontic–Modal (DM) unit does not itself require analysis through the sevenfold ontotype criteria, as it is not a conceptual field but an applied structure—a covenantal mechanism by which relationally aligned beings translate God-defined kinds into moral action. Yet its proper function presupposes ontological integrity. The axiological core must affirm fixed divine goods; the deontic layer must obligate what God has assigned; and the modal expression must operate within the bounds of legitimate instantiation. In this sense, the DM unit is not exempt from the sevenfold standard—it enacts it.

Footnotes

*

Clarifying the use of “Prevenient Grace” in this relational-ontological framework: Unlike the classical Arminian view, which frames prevenient grace as passive enablement, this relational-ontological model understands prevenient grace as active confrontation with ontologically real truth—truth instantiated by God. It does not merely remove moral incapacity but places the soul under covenantal obligation, summoning a volitional response. Grace here is not ambient or abstract, but referential, morally charged, and relationally inescapable. This formulation preserves human agency while grounding divine justice: no soul is judged without having been directly confronted. This distinction is crucial to any coherent Divine Theodicy—each soul is summoned to choose, not in ignorance, but in the light of revealed truth. An optional deeper dive into this topic is presented in

Appendix C.

Paul as a case study is presented in

Appendix C1.

**Note the coordinating conjunction “and” here is intentional and morally loaded: it binds kingdom loyalty to the pursuit of righteousness as co-equal in priority. One without the other is incomplete in God’s order.

^Though prevenient grace requires at least one decisive moral confrontation, Scripture testifies to the mercy of repeated appeals—whether through conscience, crisis, providence, or prophetic voice. God is not obligated to confront more than once; He is just in a single summons, yet merciful in many; “I spake unto you, rising up early and speaking, but ye heard not; and I called you, but ye answered not” (Jer. 7:13); “the LORD hath sent unto you all his servants the prophets, rising early and sending them; but ye have not hearkened” (Jer. 25:4). Hosea portrays God as a nurturing Father who persistently draws Israel with “bands of love,” yet they turn away (Hos. 11:1–4). Christ’s lament—“how often would I have gathered thy children... and ye would not” (Matt. 23:37)—echoes this same divine persistence. Even the hardened Pharaoh was confronted ten times (Exod. 7–12); each plague served not only as judgment, but as an epideictic appeal to release Israel. Likewise, Paul appeals to God’s “goodness and forbearance and longsuffering” that leads to repentance (Rom. 2:4), and Peter affirms that “the Lord is... longsuffering... not willing that any should perish” (2 Pet. 3:9). Perhaps most explicitly, Job declares: “God speaketh once, yea twice, yet man perceiveth it not” (Job 33:14)—a universal pattern of divine outreach despite suppression. Repetition is mercy, not obligation.

Summary

In this section, we have transitioned from the activation of moral structure to the enactment of relational transformation. The conscience, once awakened, does not rest—it must either yield or retreat. For those who yield, sanctifying grace initiates a rhythm of regeneration that saturates not just judgment, but perception and desire. This is not a mechanistic process, but a relational realignment: the volitional entrainment of the self to the moral order of God. The DM unit now serves not as an object of analysis, but as the ground upon which new life is walked out.