The twentieth century witnessed a profound shift in the landscape of philosophical inquiry: from metaphysical realism to phenomenological description, from ontological grounding to subjective constitution. Philosophers like Husserl, Heidegger, Sartre, and Merleau-Ponty emphasized the first-person structure of experience, the priority of intentionality, embodiment, mood, and world-disclosure. These thinkers did not deny that reality exists, but they redefined reality as something encountered through phenomenological horizons rather than through ontological participation.

This turn offered helpful descriptive insight into the structure of lived experience, but it came at a cost: the slow but steady dislocation of truth from being, of meaning from reality, of communication from shared referents. By privileging perception over ontology, experience over structure, and interpretation over correspondence, modern phenomenology has dissolved the foundations on which meaning, morality, and mutual understanding depend.

What began as a philosophical refinement of subjective experience has metastasized into epistemic relativism, moral constructivism, and referential instability—cultural symptoms now visible in education, ethics, politics, and technology. The rise of simulation (in media, AI, and social interaction) is not a technological anomaly—it is the downstream consequence of the philosophical abandonment of ontological anchoring.

At the heart of this untethering is a simple but devastating inversion: reality is no longer the referential ground for perception, but the product of perception. Where earlier thinkers sought to align thought with what is, many modern systems assume that what is only emerges through thought—or worse, through narrative, body, culture, or will.

But meaning cannot float freely. If there is no fixed structure to reality—if all perception is contingent, all cognition emergent, and all selfhood constructed—then truth becomes whatever can be asserted, and communication disintegrates into manipulation or echo. Without a stable ontological order, no shared experience, no intersubjective reference, no moral alignment is possible.

This essay begins with the unapologetic affirmation:

Truth presupposes ontology. And ontology presupposes structure. That structure must be discovered, not invented.

The failure of modern models lies not in their description of experience, but in their refusal to submit to the ontological architecture that makes experience possible in the first place.

This essay proceeds by applying what has already been established in Ontology, Part 2—namely, that any viable model of experience, knowledge, and moral agency must uphold four irreducible ontological constraints:

These are not theoretical postulates, but discovered ontological necessities. They form the fixed structural ground for intelligibility, reference, communication, and moral judgment. The present analysis will use them not as ideas to be explained, but as axiomatic criteria by which other philosophical models will be adjudicated.

For a full treatment and justification of these four constraints—including their divine grounding and moral implications—see Ontology, Part 2 : Structural Prerequisites for Meaning and Agency in the main framework.

Intersubjectivity—the capacity of two or more agents to refer to the same object, truth, or reality—is often taken for granted in philosophical discourse. Yet it is precisely this shared access to meaning that modern phenomenological models systematically undermine. Whether in language, perception, or moral judgment, intersubjective coherence requires more than social convention or interpretive empathy. It requires a stable ontological framework—a real world, shared perceptual faculties, aligned cognitive architecture, and accountable persons.

Without this foundation, reference cannot be shared, meaning cannot be stabilized, and communication devolves into either solipsistic projection or interpretive negotiation. If one person's concept of "justice," "truth," or even "object" arises from developmental construction (as in Piaget), intentional subjectivity (as in Husserl), or embodied orientation (as in Merleau-Ponty), then the basis for shared reference fragments. In such frameworks, meaning becomes internal, contextual, and performative—detached from ontological givenness.

In contrast, true intersubjectivity presupposes ontological correspondence. That is:

Anything less than this yields only functional coordination, not referential truth. Two subjects can coordinate behavior around a social signal (like money or ritual) without agreeing on what it truly is. But such coordination is pragmatic, not ontologically grounded—and is always vulnerable to collapse when the shared fiction is no longer reinforced.

Once any of the tetradic constraints are abandoned, referential stability begins to erode.

This is not an abstract concern. These denials are now active and visible:

Modernity’s disintegration is not accidental—it is the natural consequence of abandoning ontological coherence.

Many modern models attempt to preserve one or two aspects of intersubjectivity. For example:

But intersubjective coherence is not a matter of degree. It is binary. Without all four tetradic constraints working in tandem, the communicative act loses its referential integrity.

A message with no stable referent is a gesture. A sentence with no shared structure is a code only to oneself. A speaker with no moral agency is not accountable to truth.

In this light, the tetradic constraints function not as a helpful model but as an ontological minimum. If any are absent, truth folds into relativism, persuasion, or simulation. But if all are present—grounded in divine design and relational moral structure—then shared meaning is not only possible but morally required.

The following sections will test the models of Kant, Chomsky, Piaget, Husserl, Heidegger, Sartre, and Merleau-Ponty against these constraints. The goal is not mere critique, but clarity: to show which systems preserve the possibility of shared meaning—and which, despite their sophistication, render truth impossible. The tetradic constraints outlined above are not merely diagnostic categories; they function as meta-adjudicative instruments. They do not simply evaluate whether individual philosophical claims are coherent or plausible in isolation, but whether the entire framework possesses the ontological and epistemic architecture necessary to sustain truth, reference, and moral accountability.

What follows, then, is not an exegetical or historical survey, but a structural assay: a testing of systems at the level of their capacity to preserve meaningful discourse, shared moral agency, and ontological coherence. Only those models that meet all four constraints can support the weight of intersubjective truth.

Noam Chomsky’s theory of Universal Grammar (UG) challenged both behaviorism and constructivism by asserting that language acquisition is not the result of habit, imitation, or cultural transmission, but rather the unfolding of an innate cognitive architecture. His poverty of the stimulus argument demonstrated that children acquire complex syntactic rules despite incomplete and imperfect input, suggesting that grammar is not learned—it is triggered.

Chomsky’s model places cognition not at the mercy of environment, but in possession of a deep structural scaffoldingthat precedes experience. Language, in this view, is not a social construct but a manifestation of a pre-structured capacity embedded in the human mind.

"The language faculty is like an organ—it develops according to internal design, given minimal input." — Chomsky, various

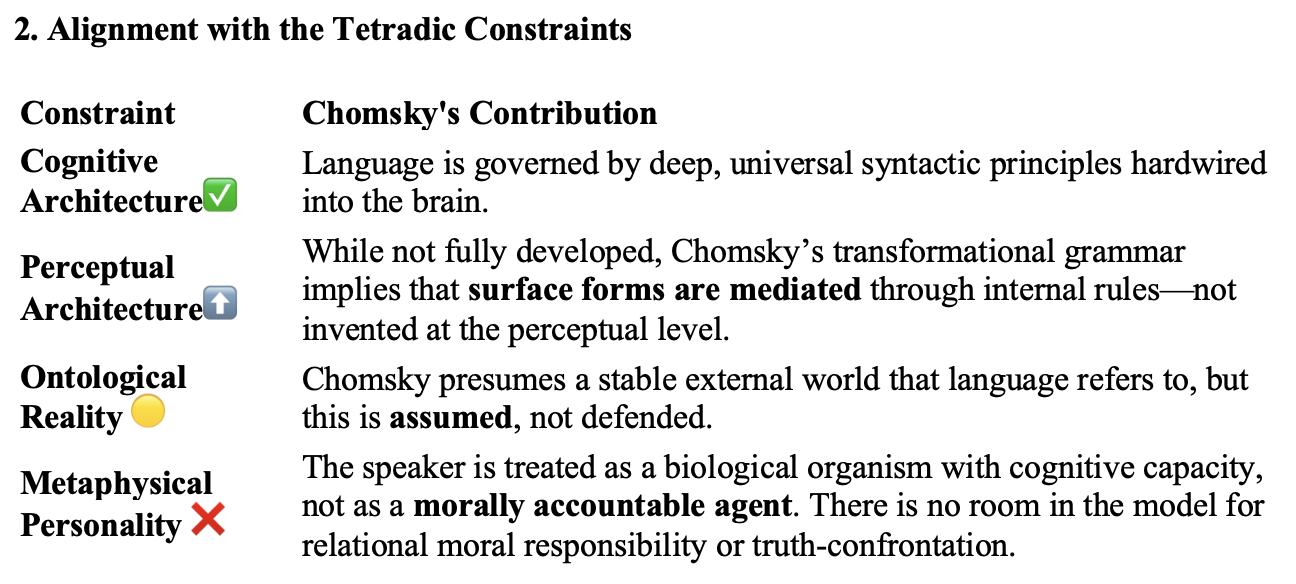

In doing so, Chomsky restores one of the most essential tetradic pillars: the Cognitive Architecture.

Chomsky therefore gives us a powerful confirmation of structural necessity within cognition but leaves perceptual grounding and moral agency undeveloped. His model is formally rational but ontologically thin.

Strengths:

Limits:

Chomsky’s contribution is crucial because it reverses the cultural narrative that language is a malleable, social product. His work implicitly rebukes postmodern linguistics, showing that there is a fixed architecture within which language must operate.

However, because he avoids metaphysical commitments, his work is often co-opted by systems that retain structure but evacuate meaning—i.e., AI simulation, formalism without accountability, or linguistic determinism.

Chomsky’s work confirms that cognitive structure is not optional—but it does not explain why that structure exists, who is responsible for truth within it, or how it is morally constrained.

For these answers, one must proceed beyond Chomsky to an ontological grounding of cognition in metaphysical personhood—which the relational-ontological model provides.

1. Core Contribution: The Mind Structures Experience A Priori

Immanuel Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason (1781) revolutionized modern philosophy by arguing that the mind does not passively receive experience; rather, it actively structures it through a priori categories and forms of intuition (space and time). These categories—such as causality, substance, quantity, and necessity—are not derived from experience; they are the preconditions for experience to be intelligible at all.

Kant’s move was to place the conditions of knowledge within the subject, but not as subjective opinion or construct. These were universal cognitive structures shared across all rational agents. Without these, no experience could be synthesized, no objects could appear, and no judgments could be formed.

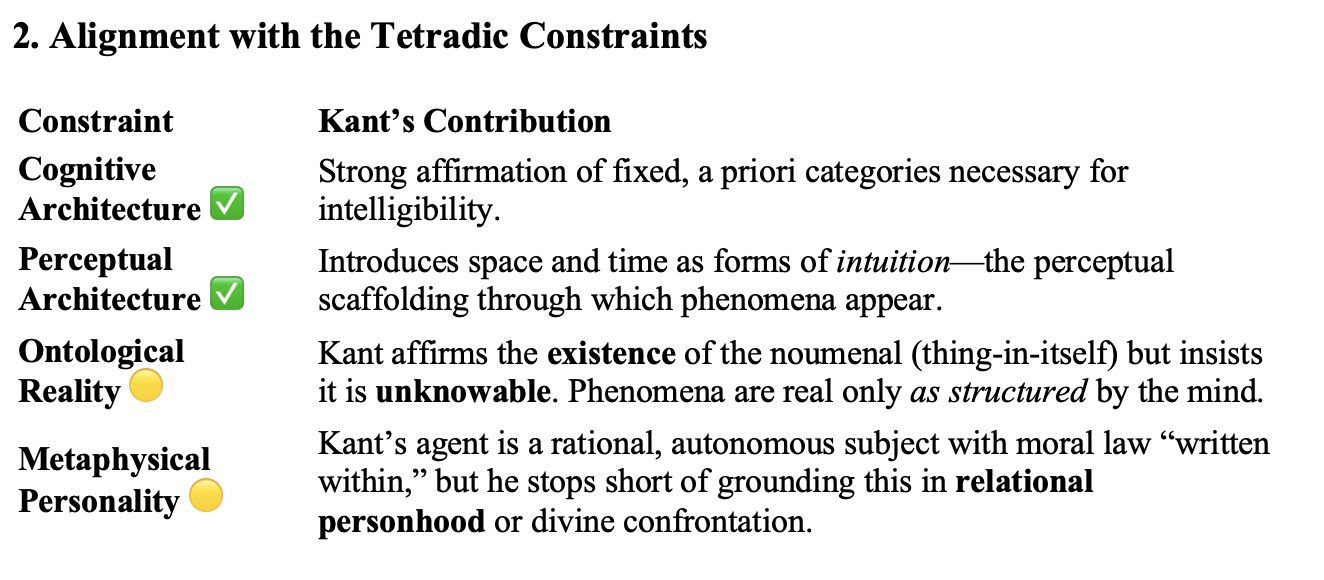

This philosophical architecture directly affirms the necessity of cognitive form—providing a powerful theoretical basis for the Cognitive Architecture in the tetradic model.

Thus, Kant gives us a transcendental framework that confirms the necessity of structure, but he inverts ontology, locating all access to meaning within the filtering mechanism of the subject, not within relational alignment to objective being.

3. Strengths and Limits

Strengths:

Limits:

4. Relevance to the Collapse

Kant is both a bulwark against collapse and a harbinger of its inevitability.

He safeguarded the necessity of cognitive form and the universality of moral reasoning, rescuing both from relativism and subjectivism. His system shows why structure is indispensable—why the mind must be equipped to receive and organize experience. But by confining knowledge to phenomena and denying access to noumenal reality, Kant ultimately severs truth from ontological participation. His framework preserves necessity without correspondence, structure without referential grounding, and moral law without relational accountability. Kant preserves structure, but leaves truth suspended above being; he rescues logic, but disconnects it from reality; he secures duty, but abstracts the person.

Only by restoring ontological correspondence and moral personhood—as the relational-ontological model does—can the strength of Kant’s structure be preserved without dissolving into formalism or idealism.

With Chomsky and Kant, we now have two vital pillars:

But both stop short of grounding these structures in a divine, relational, ontologically fixed order.

We now turn to the thinkers whose models reject or invert one or more tetradic constraints—beginning with Jean Piaget.

[Piaget The Construction of Reality in the Child (1955)]

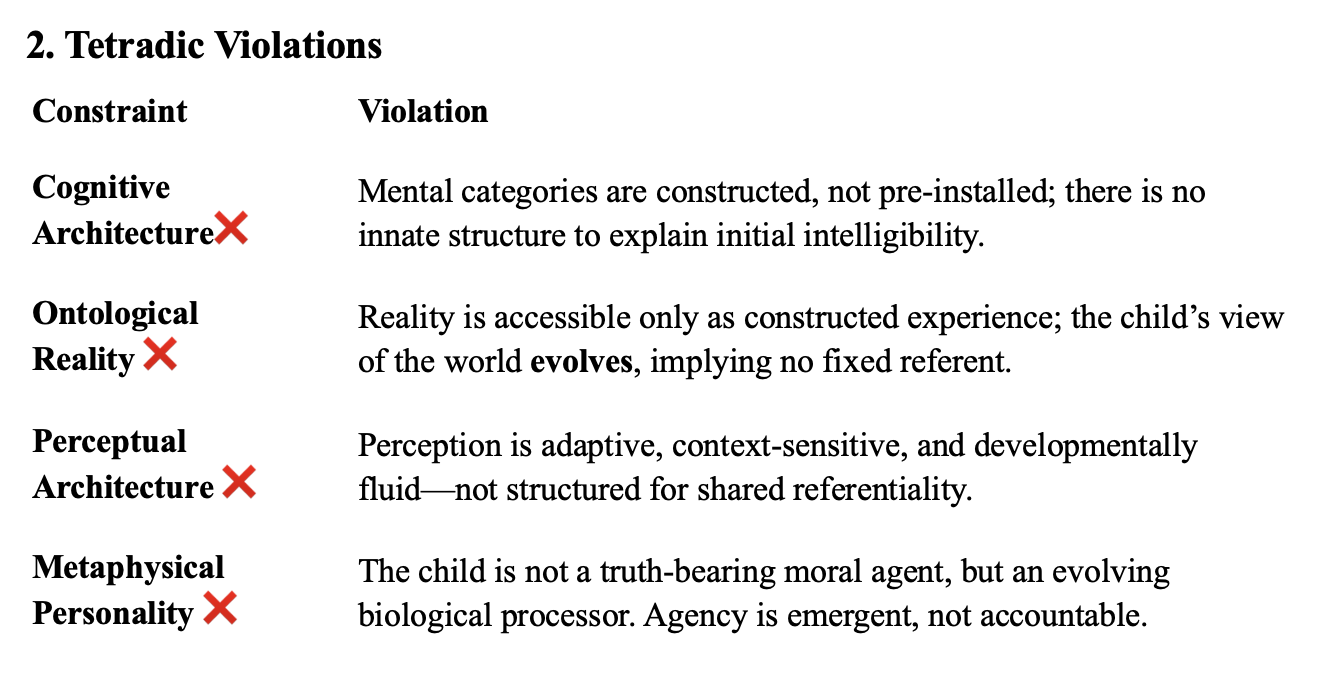

1. Core Claim: Cognition Emerges Through Developmental Construction

Piaget's constructivist epistemology proposes that children actively build categories of knowledge through interaction with their environment. Through a sequence of developmental stages—sensorimotor, preoperational, concrete operational, and formal operational—the child progresses toward abstract reasoning, spatial awareness, and moral understanding.

For Piaget, concepts such as causality, time, number, and object permanence are not innate—they are emergent outcomes of adaptive equilibration. Mental structures are built from the ground up, not installed from above.

3. Consequences of Collapse

Language loses referential fixity—words point only to internally constructed categories, not real-world entities.

Truth becomes developmental—not correspondent, but stage-relative.

Moral reasoning becomes sociocognitive adaptation, rather than a response to ontological good.

Intersubjectivity becomes behavioral synchronization, not referential alignment.

The child becomes a constructor, not a participant in divine order—truth is not received, but fabricated through interaction.

4. Final Adjudication

Piaget’s framework fails all four tetradic constraints. Though descriptively useful in educational psychology, his model cannot sustain truth, reference, or moral accountability. He confuses cognitive maturity with ontological discovery, and reduces knowledge to functional adaptation, rather than alignment with reality. Piaget does not describe how we come to know what is— He describes how we come to construct what functions. This dissolution of ontology into development makes him philosophically and theologically incompatible with the relational-ontological model.

[Husserl Ideas (1913)]

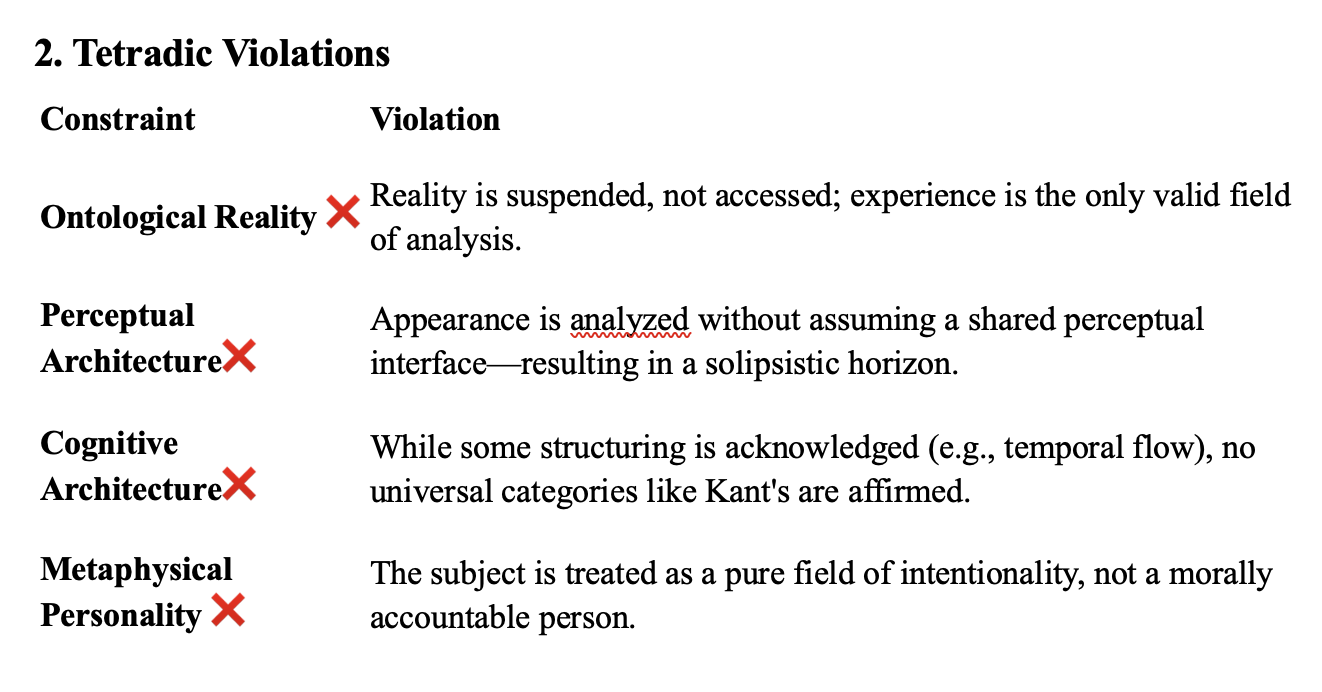

1. Core Claim: Intentionality as the Structure of Consciousness

Husserl’s phenomenology redefined consciousness as inherently intentional—always directed toward something. His method of epoché (bracketing) suspends all ontological commitments in order to analyze the structures of lived experience. The aim is not to deny reality, but to set it aside, focusing instead on how things appear to consciousness. Though Husserl sought a rigorous foundation for experience through a “science of appearances,” his method brackets ontology so completely that the result remains epistemically isolated and metaphysically inert.*

3. Consequences of Collapse

Truth is reduced to description of experience, not correspondence with being.

Intersubjectivity becomes an inferred structure, not a shared encounter with reality.

Reference becomes phenomenally conditioned—language no longer binds us to what is, but to what appears.

There is no ontological weight to conscience, perception, or logic—they are experiences, not obligations.

4. Final Adjudication

Husserl folds ontology into subjectivity. He suspends the real in pursuit of structural clarity, but thereby loses truth as confrontation. His analysis is introspective, not relational; structured, but not anchored. The world, in Husserl, becomes a mirror of intention, not a reality to which the person is morally bound. Thus, his model fails all four tetradic constraints, rendering it structurally elegant, but ontologically non-committal.

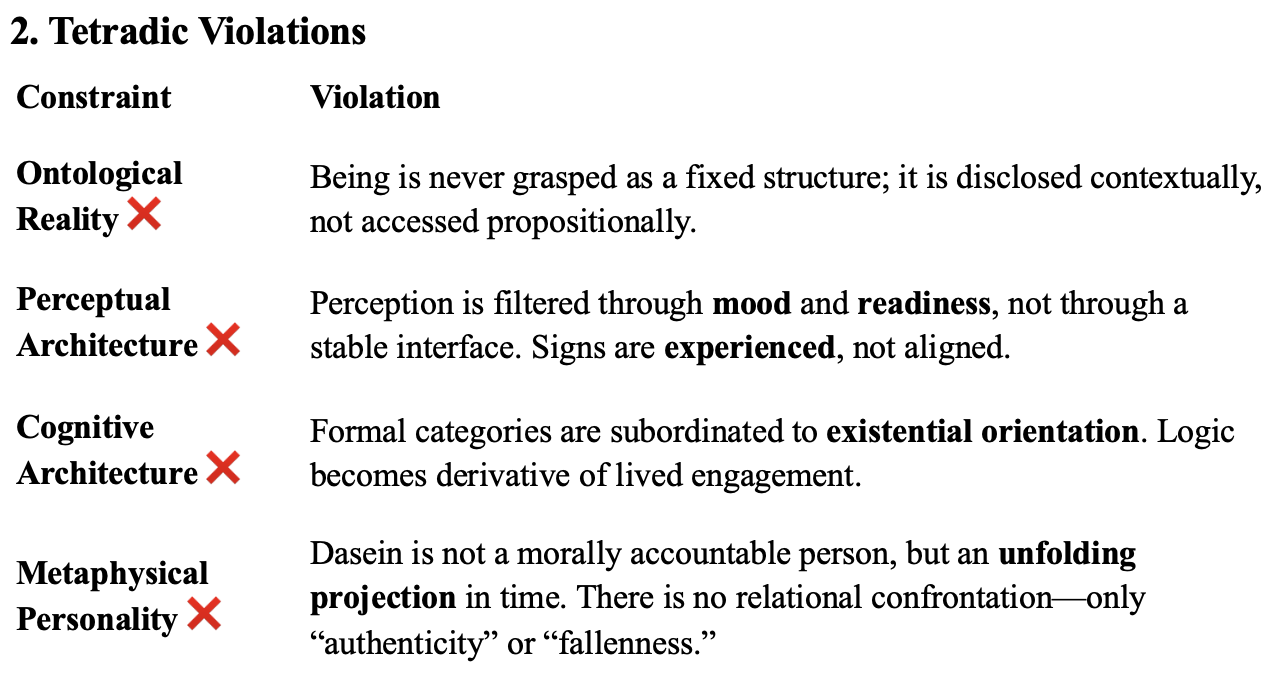

[Heidegger Being & Time (1927/1962)]

1. Core Claim: Being is Disclosed, Not Defined

Heidegger rejected both traditional metaphysics and subject–object epistemology in favor of a radically existential account of being. For him, the human being—Dasein—is not a neutral observer but a being-thrown-into-the-world, already embedded in mood, history, culture, and care. Rather than seeking knowledge about the world, Dasein exists in a pre-theoretical relation of attunement and disclosure.

Heidegger replaces objectivity with disclosure—things “uncover” themselves through use, mood, and readiness-to-hand. There is no fixed referential center. Instead, being is experienced situationally and temporally, not as substance but as flow and orientation.

3. Consequences of Collapse

Language becomes poetic disclosure, not referential speech. Naming becomes evocative, not propositional.

Moral responsibility is replaced with authenticity—a subjective relation to one's own finitude.

Truth is no longer correspondent—it is aletheia: un-concealment within a context, with no absolute referent. Even if un-concealment is a mode of access, it lacks moral anchoring or ontological fixity

The agent is not judged by truth, but by whether they are "authentically situated" in their being.

4. Final Adjudication

Heidegger dissolves structure into encounter, but the encounter is ungrounded. His vocabulary gestures toward seriousness—being, death, finitude—but without a stable referent, these become existential shadows.

Heidegger names the void with reverence but never crosses into truth. The world becomes meaningful, but never real. The self becomes situated, but never accountable.

Heidegger fails all four constraints. His work is poetically forceful but metaphysically evasive, leaving experience untethered to reality, and agency unmeasured by truth.

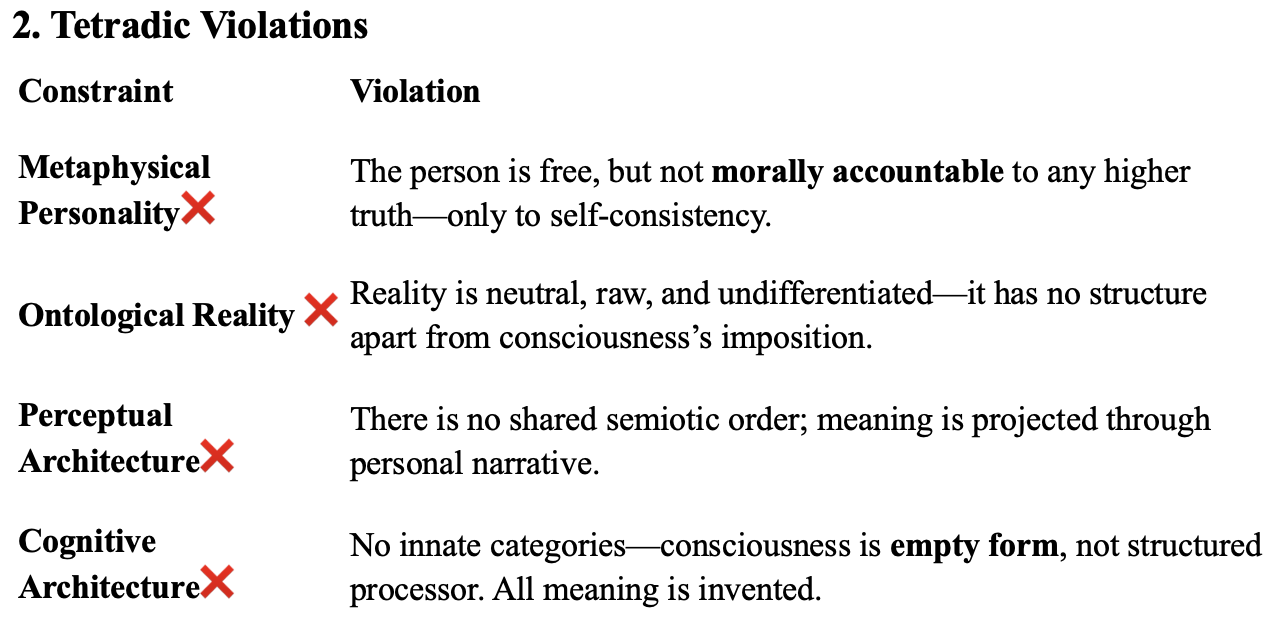

[Sartre Being & Nothingness (1943/1956)]

1. Core Claim: Consciousness Is Negation; Meaning Is Projected

Sartre's existentialism begins with the idea that existence precedes essence—there is no human nature, only human freedom. Consciousness is a nothingness, a pure negation that defines itself only in relation to what it is not. The human being is condemned to be free, thrust into existence without given meaning, and left to construct meaning through choice.

Unlike Heidegger’s attunement, Sartre’s subject is detached and sovereign, but also homeless and unmoored. There is no pre-existent structure, no divine call, no shared order—only individual projection.

3. Consequences of Collapse

Truth becomes authenticity to self—a project, not a standard.

Language is an act of freedom, not a response to reality.

There is no referent—only the meaning one chooses to impose.

Even the self is unstable, defined only by negation of what it is not.

4. Final Adjudication

Sartre is the logical endpoint of autonomy severed from ontology. His subject is free—but free to invent, not to align. Moral acts have no ontological weight. Truth is a story told to oneself.

Sartre gives the will total freedom, but removes the world to which it could be accountable.

His model destroys all four tetradic pillars—it is freedom without architecture, negation without grounding, consciousness without creation.

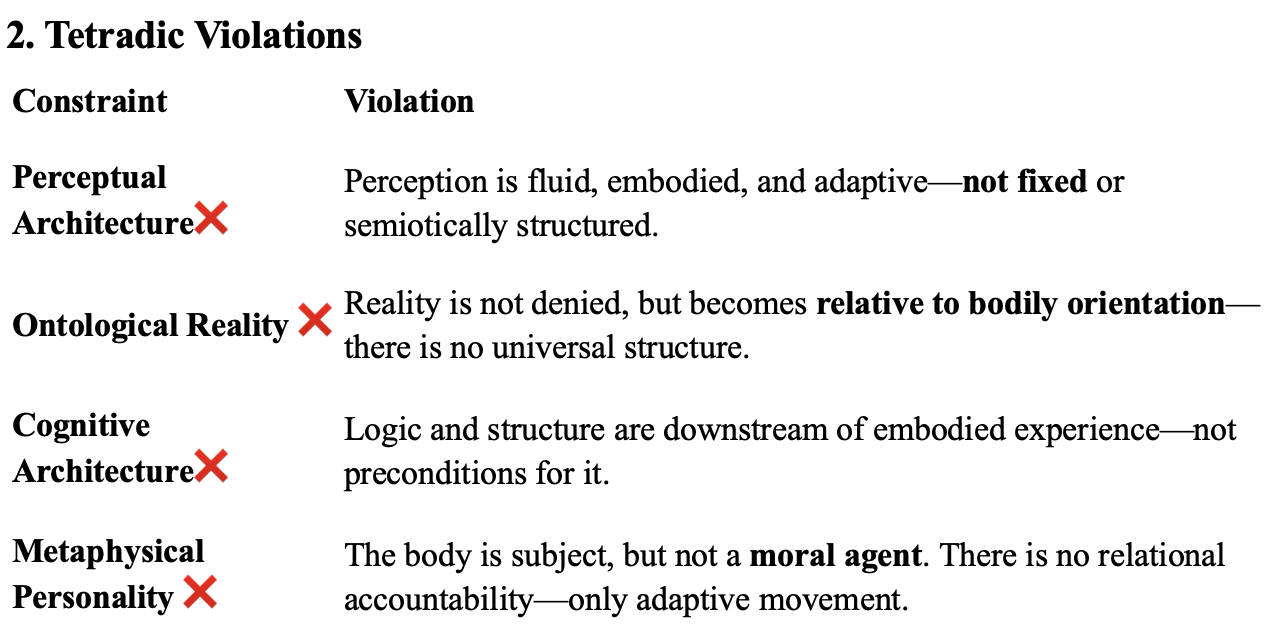

[Merleau-Ponty Phenomenology of Perception (1945/1962)]

1. Core Claim: Perception Is Embodied, Pre-Objective, and Emergent

Merleau-Ponty’s phenomenology centers on the body as subject, not object. Perception is not a detached act of cognition, but a lived, bodily engagement with the world. We do not stand above or apart from experience—we are immersed in it.

In contrast to Cartesian dualism or Kantian categories, Merleau-Ponty affirms a pre-objective layer of meaning that arises from our sensorimotor being-in-the-world. Meaning is discovered in interaction, not by abstraction.

3. Consequences of Collapse

Truth becomes lived coherence, not objective correspondence.

Communication becomes gesture, not proposition.

The body becomes the ground of meaning—but meaning is dynamic, not stable.

Shared reference is possible only in proximity, not universality.

4. Final Adjudication

Merleau-Ponty re-enchants perception but unmoors it from structure. His affirmation of embodiment is important—but without fixed categories, objective reality, or moral agency, perception becomes flux.

He recovers sensation, but loses reference. He honors the body, but cannot explain the truth. His subject is present, but not responsible.

His model violates all four constraints, though it is perhaps the most sympathetic failure—because it grasps something real, but refuses to anchor it ontologically.

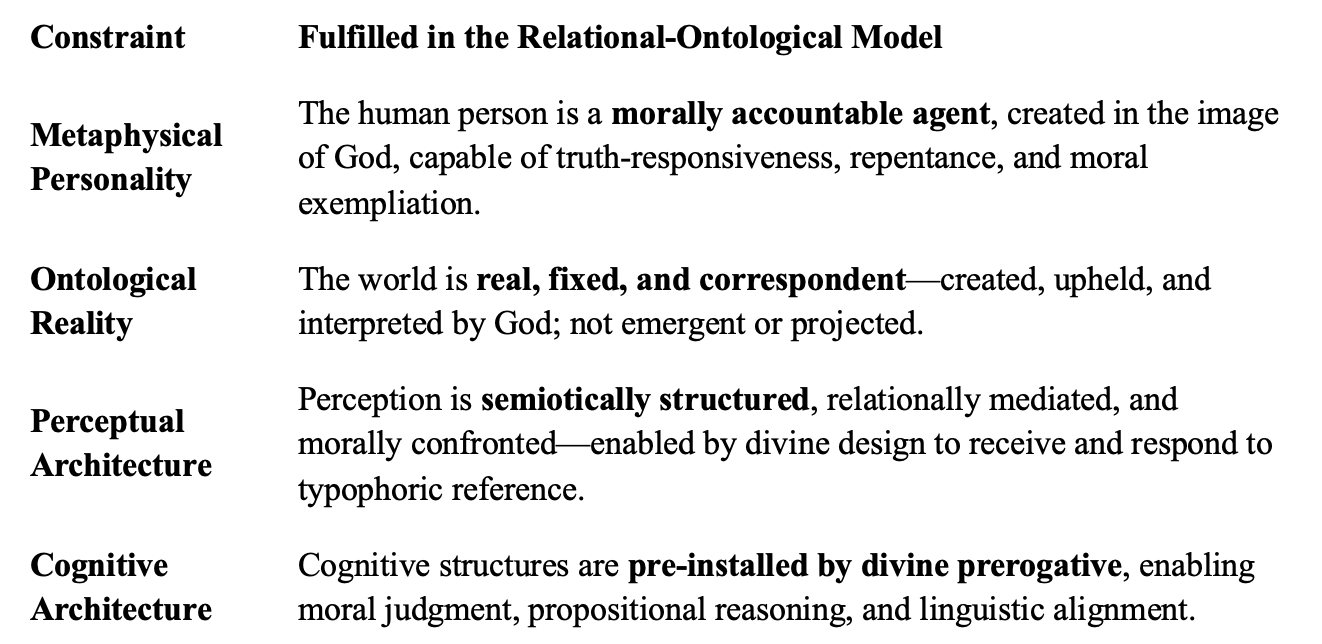

The preceding analysis has revealed that no modern phenomenological model—apart from limited aspects of Kant and Chomsky—successfully preserves the full set of tetradic constraints. Whether by bracketing reality (Husserl), dissolving structure into projection (Sartre), or reducing perception to adaptive embodiment (Merleau-Ponty), each system ultimately abandons one or more of the necessary ontological grounds for stable reference, moral agency, or cognitive coherence.

These failures are not peripheral. They are structural. The absence of any one constraint leads not to a weaker philosophy, but to philosophical and moral destruction. Without all four, communication becomes manipulation, perception becomes solipsism, and truth becomes preference.

The Relational-Ontological Model answers this collapse not by retrieving each constraint independently, but by showing that they are unified in divine moral architecture. They are not abstract categories; they are structural realities rooted in the being and will of God, and reflected in the moral design of humankind.

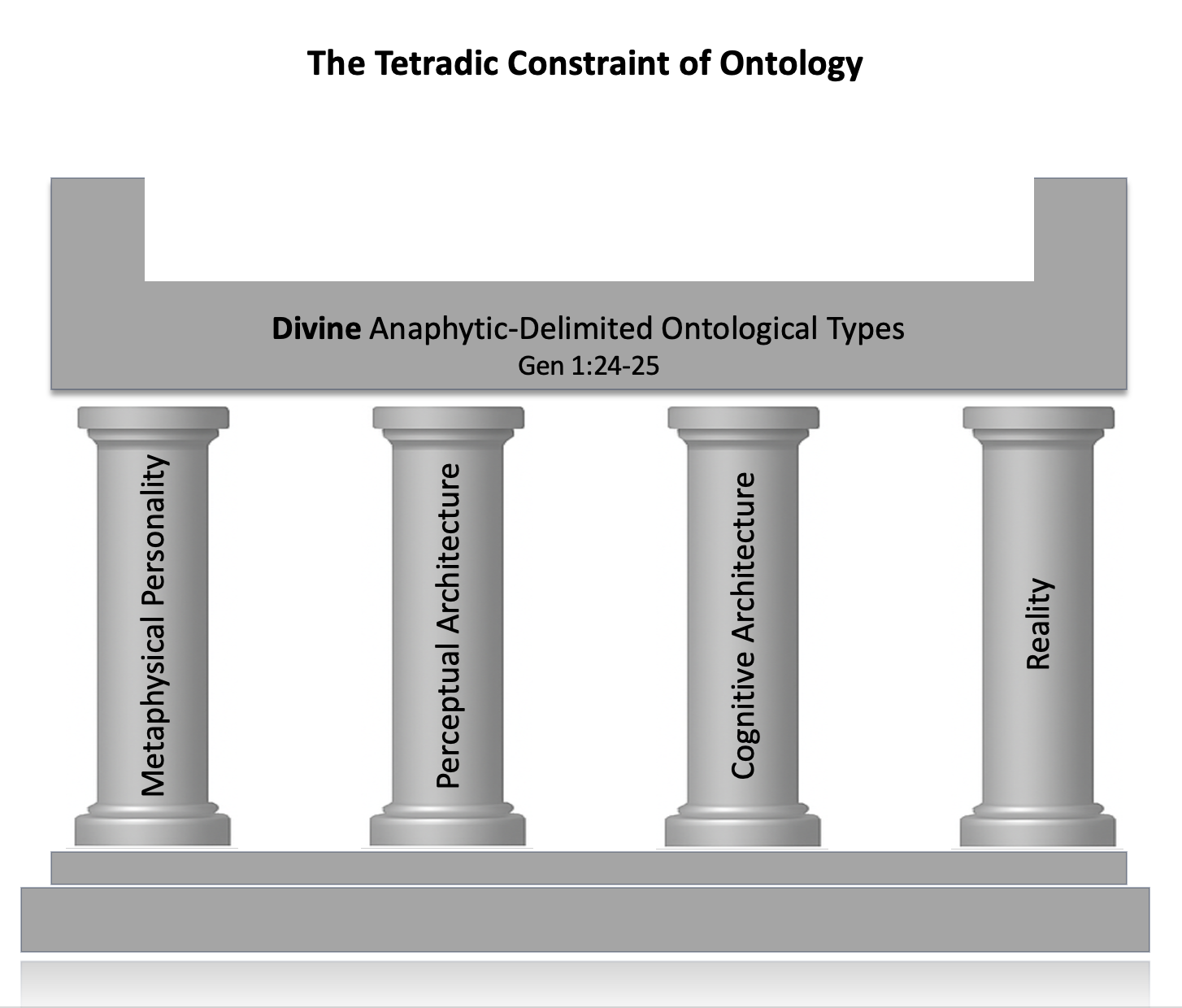

These four are not layered accidents of evolution or emergent symmetries of subjectivity—they are necessary components of a morally ordered creation. The following digram is reproduced from the Ontology Part 2

essay.

Legend: The Tetradic Constraint of Ontology

These four pillars represent the minimal ontological preconditions for any stable referent. Together they define the divine-anaphytic boundaries of creaturely being:

Metaphysical Personality – Moral and volitional distinctiveness rooted in divine image-bearing.

Perceptual Architecture – Sensory design enabling external apprehension.

Cognitive Architecture – Internal logic enabling interpretation and judgment.

Reality – The ordered, kind-differentiated world, instantiated by divine fiat.

Any genuine ontological type must exist within these four constraints.

Attempts to redefine, relativize, or bypass them are self-invalidating, as they presuppose the very conditions they deny.

This is not a descriptive model—it is a preconditional frame for all being, knowing, and naming.

Ontology cannot be dismantled without collapsing the platform of intelligibility itself.

The models we examined earlier attempt to simulate coherence while severing it from its ground. They retain rhetoric, sensation, or intentionality—but without ontological reference or moral weight.

In contrast, the relational-ontological model insists that truth is not an emergent agreement, nor a cognitive projection, nor a poetic unveiling—it is a relational confrontation. It comes from outside the self, requires moral humility to receive, and binds the agent to its implications.

Truth confronts the soul with the demand to align—not just to perceive, but to submit. This makes truth not just a feature of cognition, but a matter of moral posture.

Only a model that begins with ontological givenness, proceeds through relational design, and ends in moral accountability, can:

Sustain shared reference (intersubjectivity),

Ground truth-telling in obligation, not expression,

Explain why semiotic coherence is necessary and meaningful,

Preserve the unity of being, knowing, and speaking,

And resist the collapse into simulation, relativism, or existential drift.

It succeeds precisely where the others fail—because it does not begin with the self. It begins with divine initiative, ontological design, and the invitation to covenantal participation.

In the relational model, epistemology is not the construction of meaning, but the response to meaning already embedded in reality. To know is to be confronted—by the object, by the Word, by conscience—and to either align or rebel.

This epistemology has moral dimensions:

It distinguishes authentic reference from pseudo-instantiation.

It anchors deixis, implication, and typophora in real ontological types.

It enables real intersubjective discourse grounded in a common frame.

Knowledge becomes not possession, but fidelity; not imposition, but alignment.

The modern phenomenological tradition—however nuanced or well-intentioned—has failed to safeguard the conditions necessary for truth, reference, and meaning. Its pivot toward the self, embodiment, projection, or intentionality may offer rich experiential texture, but none of these paradigms can support intersubjective coherence unless they are grounded in ontological reality and moral structure.

What began in Kant as an attempt to rescue knowledge from metaphysical chaos ended, by the time of Merleau-Ponty and Sartre, in a diffused dissolution of truth itself. Without metaphysical personality, perception becomes persuasion. Without ontological reality, language becomes simulation. Without perceptual and cognitive architecture, all structure is either fabricated or retrofitted for convenience. Collaborations like LIGO¹ presuppose ontological fidelity—precisely what the tetrad secures.

The Relational-Ontological Model, by contrast, does not simply reassert dogma or reverse the Enlightenment. It rebuilds the structure from the ground up, showing that:

Being is real and ordered,

Cognition is structured for reception and alignment,

Perception is morally shaped for typophoric discernment,

And personality is the locus of accountability to truth.

Truth does not emerge from synthesis. It confronts the agent—personally, ontologically, and relationally. The tetradic constraints are not theoretical options; they are existential preconditions for coherence in speech, thought, and moral life.

Only when these constraints are restored—not merely observed—can the unravelling of language, meaning, and moral agency be reversed.

What remains, then, is not only critique, but invitation:

An invitation to return from simulation to substance,

From structural drift to ontological fidelity,

From disintegrated perception to moral encounter.

Recovery is not a function of theoretical elegance but of ontological repentance- here meaning turning from ontological self-authorship to receptivity before divine order. The failure of the modern mind is not intellectual—it is relational. And the way forward is not just structural repair, but relational submission to the One who authors reality, structures cognition, sustains perception, and confronts the soul.

The tetradic constraints are not abstractions. They are signatures of the divine. And they are the foundation upon which a meaningful world—and faithful knowledge—can be built again.

Footnotes:

*Husserl’s phenomenology was not intended as a metaphysical denial but as a preparatory discipline—a “science of appearances” (Wissenschaft von den Erscheinungen)—focused on the structures of consciousness rather than external reality. However, by permanently suspending ontological commitment through epoché, his system forfeits the very grounding needed to secure stable reference or moral accountability.

¹ LIGO (Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory) is a multinational physics collaboration that achieved the first direct detection of gravitational waves in 2015. Its success depends on precise instrumentation, intersubjective calibration, and moral accountability to empirical truth. As such, it tacitly presupposes the tetradic constraints: an ontologically real cosmos, a cognitive-perceptual apparatus structured for correspondence, and morally responsible agents committed to epistemic fidelity.