Part I diagnosed the fracture in modern ontology; Part II puts that fracture under a forensic lens. Here we ask not merely what has collapsed, but how the collapse is perpetuated and concealed. The answer is rarely innocent. Many contemporary frameworks operate as evasive mechanisms—suppressing the real, displacing the Source, and masking divine referentiality.

This section therefore traces the recurring strategies by which ontological rebellion sustains itself: nominalist dissolution, ontological flattening, constructivist substitution, antiteleological drift, and—most subtly—the covert borrowing of divinely grounded a priori categories. These tactics are weighed against biblically anchored criteria for legitimate kinds—criteria that are not speculative abstractions but moral entailments of God's prerogative to define and instantiate being.

To uncover and assess these evasions, we first introduce several foundational concepts:

The seven ontotype criteria, which provide a structured rubric for recognizing legitimate kinds;

The Tetradic Constraint of Ontology (TCO), which outlines the four structural preconditions that make denial thinkable even as they render it incoherent; and

The diagnostic lens of Parasitic Cognition, which reveals how every act of ontological rebellion depends on what it seeks to overthrow.

These concepts provide not only a vocabulary for critique, but a framework for ontological restoration. They clarify what is being denied, how denial functions, and why it ultimately collapses—because rebellion, lacking ontological autonomy, must parasitize the very reality it suppresses.

Part II, then, exposes the moral anatomy of ontological rejection and clears the ground for recovery. What is at stake is more than metaphysical precision—it is covenantal alignment. For to suppress the real is to resist the Revealer. And every evasion, however sophisticated, ultimately survives by secretly living off the very reality it denies.

Authorial Stance. The analysis that follows is anchored in revealed ontology rather than speculative abstraction. It proceeds from the conviction—established throughout the Prologue and formalized in the Ontology and Epistemology sections—that the God of Scripture exists and exercises the Divine Double Prerogative. The present appendix therefore does not seek to prove God’s existence from first principles; rather, it shows how modern ontologies become parasitic and incoherent once they suppress the ontological ground they silently borrow. For those seeking philosophical preliminaries, the foundational claims regarding necessary being and the logic of participation are addressed in the Prologue. A technical refutation of secular epistemological systems is offered in Epistemic Deep Dives (see Appendix D1).

The collapse of modern ontology is not a failure of intelligence but a refusal of submission. Secular systems—despite their conceptual diversity—share one structural flaw: they sever being from its divine ground. This rupture is not a neutral oversight; it is a volitional evasion, rooted in moral posture. Ontology is not merely misunderstood—it is deliberately bypassed.

The main body of this framework has already surveyed the broad historical trajectories of ontological thought—Thomistic essence, Kantian categories, process metaphysics, materialism, and more. This appendix does not repeat that landscape. Instead, it drills deeper: isolating the specific strategies by which ontological reality is evaded. These are not random errors, but patterned evasions—repeating the same tactics under the guise of intellectual sophistication.

In every case, the evasive maneuver is the same: displace ontological kindhood—what something is, by divine assignment—with a semantic or functional substitute—what something is called, or what it does. This substitution relies on a familiar and repetitive set of tactics:

But these evasions are structurally self-defeating. They must borrow the very stability they deny. The coherence of these systems depends on the intelligibility, recognizability, and fixity of kinds—even as they strip those kinds of ontological legitimacy. This is what this framework elsewhere terms referential fraud: systems that exploit typological coherence while disavowing its ontological basis.

This appendix does not aim to construct an alternative ontology from speculative premises. Instead, it proceeds diagnostically: by exposing the evasive patterns used to suppress ontology, it surfaces the implicit criteria they presuppose but cannot justify. The result is a sevenfold diagnostic for identifying real kinds—not through abstraction, but through relational, typological, and moral discernment.

Having identified the general strategy of ontological evasion—displacing fixed kinds with semantic or functional substitutes—we now examine how this tactic appears across major philosophical systems. Each model, though rhetorically distinct, participates in a shared project: to dissolve kindhood without relinquishing coherence. They displace ontology while secretly relying on it.

The analysis that follows does not aim to refute each system exhaustively, but to expose the specific mechanism of evasion it uses. These maneuvers fall into recognizable patterns:

What they share is a refusal of divinely assigned ontological structure—and a covert reliance on the very typology they disclaim. The exact strategy is disclosed under the heading of 'borrowed assumption.'

1. Nominalism

Tactic: Language over Being Nominalism denies real universals, positing that categories are merely names we assign to individual instances. Yet it depends on stable reference and recognizable commonality to function linguistically.

Evasion: Ontological kindhood is replaced by semantic labeling.

Borrowed assumption^: Typological convergence across referents.

Diagnostic: Semantic substitution disguised as realism.

2. Constructivism

Tactic: Discourse over Ontology Constructivism argues that what we call “reality” is produced through social agreement or linguistic framing. But it relies on a shared world in which those constructs can be mutually intelligible.

Evasion: Replaces participation in kinds with participation in narratives.

Borrowed assumption^: Intersubjective access to stable referents.

Diagnostic: Discourse replacing ontological participation.

3. Trope Theory

Tactic: Similarity over Identity This view claims that properties are not universal kinds but particularized instances—tropes—shared across objects. But it collapses sameness into resemblance, denying what resemblance presupposes: a stable referent.

Evasion: Kindhood is denied; pattern is retained.

Borrowed assumption^: Convergent (intersubjective) recognition of resemblances.

Diagnostic: Similarity used to deny identity.

4. Materialism

Tactic: Quantification over Quality Materialism collapses all being into particles, energy, or matter in motion. But this reduction destroys explanatory power for immaterial categories like justice, mind, or meaning—while continuing to invoke them in practice.

Evasion: Abstract kinds are deemed epiphenomena.

Borrowed assumption^: Qualitative intelligibility (ability to recognize and distinguish real kinds or properties not merely by quantitative metrics (like size, number, duration), but by their intrinsic nature, form, or meaning.)

Diagnostic: Qualitative kinds flattened into quantitative particles.

5. Ontological Monism

Tactic: Unity over Distinction Monism denies that real distinctions exist. All perceived difference is illusion or flux within an undivided whole. Yet monists make distinctions to articulate their claims—undermining their own ontology.

Evasion: Differentiation is dismissed as phenomenal.

Borrowed assumption^: Linguistic and logical distinction.

Diagnostic: Distinction denied through reduction.

6. Antiteleology

Tactic: Purposelessness with Purposeful Argument.

Antiteleological systems reject intrinsic ends or final causes. But their critiques are structured, goal-oriented, and aimed at persuasion—paradoxically exhibiting the very teleology they deny.

Evasion: Telic order is declared an illusion.

Borrowed assumption^: Rational coherence and purposive discourse.

Diagnostic: Purpose denied through purposeful argument.

7. Process Ontology

Tactic: Becoming over Being Process thinkers reject fixed ontological categories, privileging flux and becoming. But to identify becoming itself as a stable structure requires presupposing what it denies: enduring intelligibility. Process metaphysics rightly highlights that reality is dynamic; yet dynamism itself is intelligible only against a backdrop of recognisable kinds. Motion without a stable point of reference is indistinguishable from noise.

Evasion: Being is subordinated to motion.

Borrowed assumption^: Conceptual continuity and classification.

Diagnostic: Becoming without stable being.

^The theory covertly relies on the very ontological realities it denies or deconstructs.

In each case, we find not just error, but evasion—moral postures masked as metaphysical sophistication. These systems deny real kinds, but do so while depending on those very kinds to remain intelligible. They are parasitic upon the order they suppress. Having exposed these evasions, we are now in a position to examine the structural criteria of real kinds in Section III.

If the evasions described above systematically deny real kinds, then they also unintentionally reveal the contours of what they evade. By identifying what secular models must suppress in order to remain plausible, we uncover positive criteria for discerning true ontological kinds. These are not abstract speculations but grounded characteristics that emerge from moral, relational, and typological discernment.

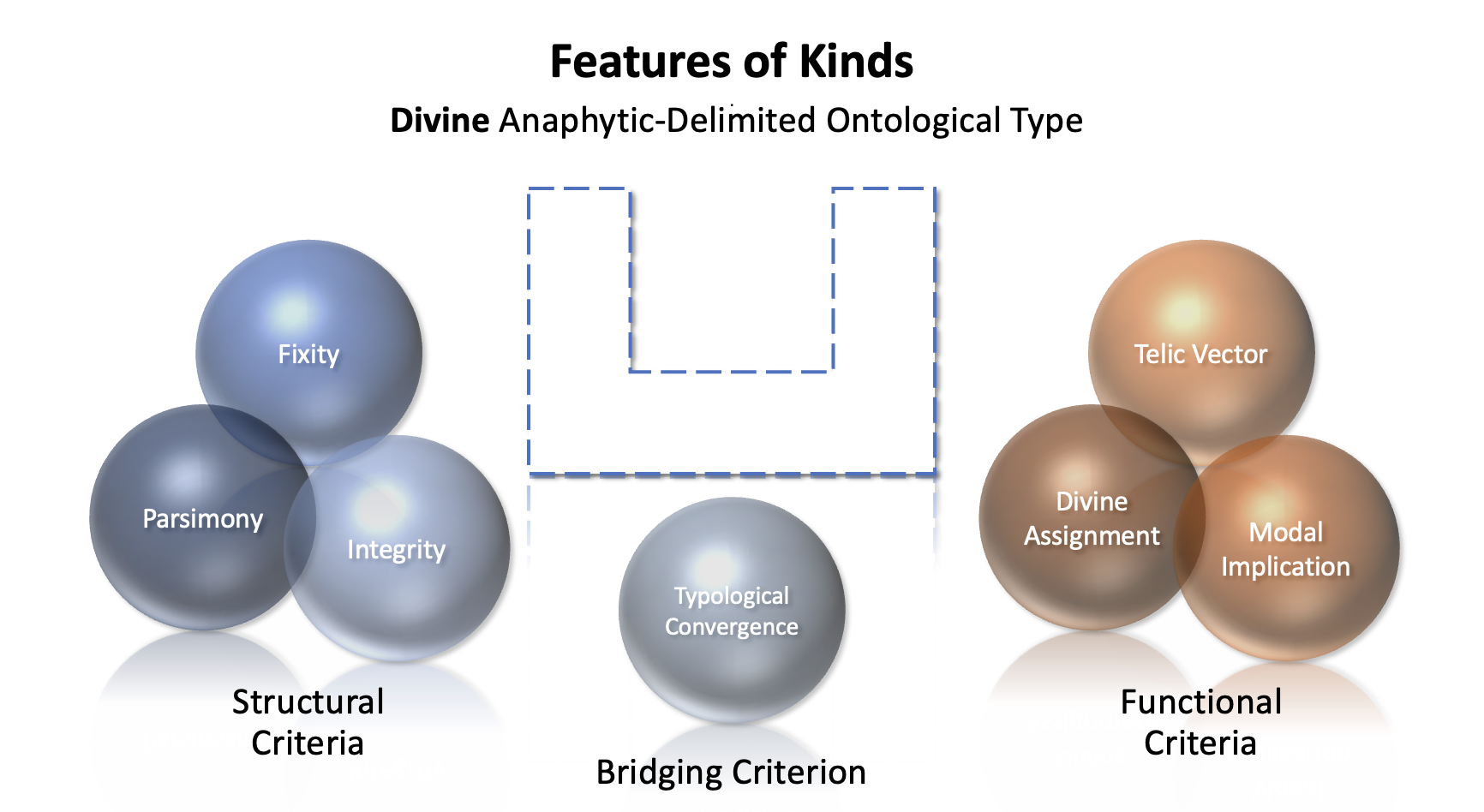

Each criterion below serves as a marker of real ontological status—distinct from semantic utility or cultural consensus. The first three are structural; the latter three are functional (moral-teleological) and the final, a bridging criterion.

Real kinds possess enduring temporal and modal stability. They do not fluctuate with perception, naming, or usage. While their manifestation may vary, their ontological type remains coherent across time and space. Fixity refers to the ontological constancy of a kind—not to the provisional labels assigned by human classification. Reclassification merely refines our recognition of what already exists; it does not create or dissolve the kind itself. Just as redefining planet in 2006 did not alter Pluto’s physical reality—only our taxonomic convention—so too the periodic table’s reordering did not change the nature of gold. These shifts adjust human models, not the types themselves. Fixity, then, describes the stable referential structure of real kinds as grounded in the authority of divine instantiation.

Integrity implies internal coherence and resistance to fragmentation. A true kind maintains its identity even when instantiated in diverse forms. It resists reduction to merely functional, perspectival, or partial accounts.

Note: Fixity is the external boundary of an ontotype; integrity, by contrast, is its internal coherence. Fixity is divinely secured and ontologically immutable. It defines the stable referential structure that resists discursive, cultural, or psychological reassignment, preserving the intelligibility and distinctness of kinds. Grounded in the prerogative of divine instantiation, fixity cannot be altered by creaturely perception or projection.Integrity, by contrast, names the moral, relational, and axiological harmony of a being as it faithfully participates in its assigned type. It reflects the alignment of will and purpose within that structure. While integrity may be preserved or violated, it does not compromise the external fixity of the type itself. Fixity secures ontological constancy; integrity expresses covenantal fidelity within it.

Ontological kinds are economical: they do not proliferate without necessity. This is not minimalism for its own sake but reflects divine order—where multiplicity serves purpose, not confusion.

Parsimony and Divine Ground. Invoking a single Author of kinds reduces rather than enlarges ontological commitments: instead of positing an unbounded set of brute particulars or ever-splintering tropes, it anchors multiplicity in one intelligible source. Divine assignment therefore satisfies parsimony more elegantly than secular models that must multiply entities—or hidden explanatory layers—to account for the same regularities.

Fixity, Parsimony and Integrity can be viewed as structural indicators . They reveal the coherence and stability of kinds across instantiations. Pragmatic and causal theories of meaning still presuppose ontological regularity: a term can “work” or a causal chain can “fix reference” only if the underlying kind remains stable across occasions of use. Without Fixity, Parsimony, and Integrity, even pragmatic success would dissolve into flux, and reference would cease to track anything beyond momentary convention. In other words, Pragmatism and causal reference still need real, unchanging kinds in the background; otherwise their ‘successful use’ would disintegrate. So they secretly depend on the very structural features—Fixity, Integrity, Parsimony—that secular theories want to dismiss

True kinds carry with them modal entailments: what they permit, forbid, or require. These are not added afterward by convention; they are embedded in the type.

The moral weight of a kind does not arise from social consensus or evolutionary utility; it flows from the Creator’s authority to designate reality (auctoritas essendi) and to prescribe its right use (auctoritas instantiandi). The argument for objective modality, therefore, rests on the same divine prerogative that grounds typological fixity. A fuller defense of moral realism appears in the Epistemic Deep Dives, Appendix D1 (Gettier and Reliabilism critiques), where we show that normativity cannot be derived from descriptive states without covertly re-importing an ontological source.

Ontological kinds are not inert—they lean. Each has a directional arc or moral telos built into its structure (e.g., justice aims toward restoration, not annihilation).

Even in cases like cancer or parasitism, we do not observe alternative ontological types but distortions of existing ones. These are not neutral evolutionary alternatives but disordered expressions of previously functional categories. Cancer does not instantiate a new kind; it manifests a telic inversion of normal biological fidelity. While Scripture does not itemize such patterns in cellular terms, it does describe the world’s subjection to futility (Rom 8:20–22) as a direct consequence of ontological rupture—where kinds retain structural traits but fail in covenantal purpose. In this light, cancer may be understood as an anamorphic effigiation—a corrupted echo of typological integrity, lacking telic faithfulness.

We discuss effigiation in detail in Ontology and Morality essays.

They are assigned by divine prerogative—a concept elsewhere termed typological delegation or onto-taxonomic authority of the Divine Double Prerogative.

Kinds are not human constructs.

Their reality is not up for negotiation because it is not ours to define. God sets the intrinsic, non-negotiable essence of a kind (its “critical type-design”), while allowing considerable extrinsic variability in how that kind is instantiated, named, or even misused in human cultures. Thus divine assignment is the cause of fixity, not merely another description of it; it grounds ontological stability in an ultimate authority rather than leaving it unexplained. Divine assignment is not a temporal act alongside created causes; it is the metaphysical ground in which kinds participate—akin to Augustinian exemplarism, where each type subsists in the Logos and is instantiated through providence. Participation metaphysics (Aquinas, Augustine) treats created kinds as finite reflections of eternal exemplars in the divine intellect; the “mechanism” is not physical causation but ontological dependence.

Modal Implication, Telic Vector, and Divine Assignment—serve as functional indicators. They disclose not just what something is, but what it means and why it matters. Divine Assignment, while foundational, is placed in the functional triad because it marks the decisive act of ontological instantiation—the moment in which kindhood is not only possible but actual. Unlike modal or teleological properties which describe outflow, Divine Assignment is both foundational and functional: it points back to authoritative origin. It is the grounding act that gives the kind its integrity, fixity, telic direction, and moral weight. It is the prerogative of instantiation that no created agent can simulate.

Real kinds are mutually recognizable. Despite cultural, linguistic, or perceptual differences, they exhibit intersubjective convergence—a shared witness to fixed referents across time and space. It bridges the two clusters.

Clarification on Variability: convergence does not mean every society applies a kind uniformly; it means the conceptual recognition of the kind persists even where applications are distorted. Cultures that practised slavery still had a category for unjust killing and still coded betrayal as morally blameworthy. Disagreement over who is protected reveals moral error, not the absence of the kind itself. Thus, historical divergence in practice confirms rather than refutes the universality of the underlying type. E.g., cross-cultural surveys show near-universal disapproval of unprovoked lethal violence (Fry 2012); ritual exceptions prove the rule by requiring special justification.

This diagram outlines the seven key features by which a Divine Anaphytic-Delimited Ontological Type—or real kind—is discerned. These features are not arbitrarily selected but emerge from the biblical and philosophical recognition that kinds are not humanly constructed, but divinely assigned and morally bounded.

The Structural Criteria (Fixity, Parsimony, Integrity) describe the kind’s ontological architecture: it is stable, bounded, and irreducible. The Functional Criteria (Divine Assignment, Telic Vector, Modal Implication) describe how a kind behaves within created moral order. Here, Divine Assignment is both foundational and functional—marking the ontological act by which the kind is instantiated and the referential anchor from which its moral and teleological features follow.

The Bridging Criterion, Typological Convergence, expresses how real kinds are recognizable across cultures and contexts. It functions as the evidence of objective kindhood, discernible through intersubjective recognition and common experience.

Together, these seven features form a cohesive framework for testing the authenticity of any claimed category. They reveal whether a proposed kind is ontologically grounded or merely semantically constructed—and whether it carries the weight of divine origin or functions as an artifact of human autonomy. Reference: Genesis 1:24–25 — "after his kind… and God saw that it was good."

Note: To our knowledge, this is the first formal articulation of ontotype validation criteria that integrates ontological, axiological, modal, covenantal, and semiotic dimensions. Prior theological and philosophical traditions have implicitly presupposed or approximated aspects of these features, but not codified them into a unified diagnostic model.

Beyond serving as positive descriptors of genuine kinds, the above seven criteria supply a diagnostic grid—a seven-fold test—for evaluating any purported type, code, or token. When each feature is applied in sequence, effigiation and pseudo-instantiation quickly surface:

Fixity — Has the sign respected the God-secured boundary of the kind, or attempted reassignment?

Integrity — Does it preserve the type’s internal moral and axiological coherence, or fracture it?

Parsimony — Is the claim ontologically economical, or does it proliferate needless sub-types?

Typological Convergence — Do multiple instantiations converge on the same pattern, or is the type ad-hoc?

Modal Implication — Are the proposed variations within the type’s legitimate range of possibility?

Telic Vector — Does the sign honour the kind’s intrinsic purpose, or redirect it toward alien ends?

Divine Assignment — Is there a biblical or creational warrant for the type, or only human declaration?

If a candidate fails any one of these checkpoints, it is not a faithful ontotype but a simulated kind—an instance of ontological fraud. The Semiotics chapter employs this same seven-fold test when analysing codes that masquerade as moral authority. Thus, this appendix supplies both the constructive definition of real kinds and the evaluative tool for discerning their counterfeits.

These seven criteria do not exist in isolation. They are interwoven, reinforcing one another. And crucially, as the next section will show, each corresponds to a common mode of evasion. The same features that reveal ontological kinds are precisely those that secular systems seek to dissolve or defer. Empirical falsifiability: these criteria are not immune to verification, they issue predictable signatures in language, culture, and scientific taxonomy. For example, any system that denies fixity or integrity will exhibit semantic inflation (ever-proliferating identity labels), norm-evasion drift (ethical categories lose prescriptive force), and classification instability (oscillating terminologies in the human sciences). Conversely, domains that implicitly honor these criteria—e.g., the Linnaean stability of biological kinds or the durable cross-cultural condemnation of unprovoked homicide—display measurable coherence over time. Such data allow the framework to be empirically interrogated rather than merely asserted. Finally, Corpus linguistics tracks lexical inflation around human identity terms; sociological meta-analyses (e.g., World Values Survey) show persistent moral convergence despite divergent legal codes; and taxonomy studies (Hull, 1988) indicate that stable kinds underwrite long-term explanatory power.

Ontology does not end with delimitation. To know what a thing is—to perceive its ontotype—is not the final step, but the first. For once the type is known, the creature becomes morally implicated. Ontology, in this sense, confronts. It calls not merely for recognition but for alignment, not merely for reverence but for embodied fidelity. This culminates in the inescapable question: Can I instantiate what I now know?

This is the burden of ontic instantiation—the weight of transitioning from typological awareness to typologically faithful action. And not all who perceive are able, or permitted, to enact. The agent may desire to participate in truth, mercy, or justice, but the question is not merely one of desire or even conceptual understanding. It is a question of fitness, of posture, and of authorization.

The distinction between organic and inorganic instantiation sharpens this point. Organic instantiation—the bringing forth of being, kind, soul, or living form—belongs entirely to God. It is a prerogative of the auctoritas essendi, the divine right to define and originate. No creature shares this power. Even the ontotypes themselves, by which we recognize categories like justice or mercy, are established through divine delimitation and cannot be constructed or reframed by human reason.

But inorganic instantiation—the symbolic, structural, moral, or relational enactment of a type—is often delegated to human agency. This is where exempliation occurs: the faithful (or unfaithful) embodiment of a type in real time, through word, gesture, decision, and life. And here, participation is probationary, conditional, and relationally gated. See Ontology Part I for a full discussion.

Not all who claim a type are permitted to instantiate it. Not all who invoke “truth” are vessels of it. The right to instantiate is not earned by aspiration; it is conferred by reverence and alignment. Fidelity is not measured by conceptual possession, but by moral exemplification.

To desire to instantiate a type is not to do so. Aspiration is not equal to exempliation by default. In fact, in a fallen moral context, the default is not presumed fidelity, but the opposite.

Absent restored relation, the natural outcome is not fidelity, but effigiation.

This aligns with human experience and biblical anthropology: without moral reorientation, typological aspiration tends to yield distortion. The type is invoked, but its enactment is twisted—simulated, politicized, or subverted.

This is why pseudo-instantiation—effigiation—is not merely a misfire but a form of ontological fraud. It enacts without alignment. It simulates what it cannot substantiate. The one who claims justice but operates in coercion has not instantiated justice; he has effigiated it. The agent who names truth without submission to its source does not bear truth but mimics its form for private ends.

In this light, the true test of ontological alignment is not possession of theory, but expression in praxis. Judgment does not fall upon the knower alone, but upon the one who did not do. Thus, every act of exempliation becomes an open claim to typological fidelity—and will be weighed accordingly.

“Not every one that saith unto me, Lord, Lord… but he that doeth the will of my Father…” (Matt. 7:21)“By their fruits ye shall know them.” (Matt. 7:16)“Inasmuch as ye have done it…” (Matt. 25:40)

These are not appeals to works-based merit, but revelations of alignment. To know is to be called. To be called is to be judged by one's response. And that response is measured not in conceptual clarity but in ontic enactment—in what one brings into being through posture, action, and witness.

In sum, this section names a threshold principle:

Every ontotype disclosed creates an ethical horizon. The moral agent stands at that horizon not as a neutral observer, but as a potential witness—or a potential defrauder.

This is the burden of ontic instantiation:

To be morally summoned by what is known,

To be permitted only through reverent alignment,

And to be measured by what one does—not by what one claims to know.

This is not a detour into moralism. It is the recognition that ontology, when rightly received, is never inert. It reveals, confronts, and summons. Every ontotype disclosed to the moral agent brings with it a corresponding obligation—not to reinterpret, but to rightly mirror. The moral burden of ontic instantiation is thus not an add-on to ontology; it is its natural extension. For to receive a type is to be situated within its relational structure—and to refuse or misrepresent it is not merely to err, but to violate the very nature of being. Ontology cannot be divorced from accountability. There is no sterile knowledge of types. There is only witness, or fraud.

When this covenantal summons is refused, the creature does not stand neutral; it bends toward patterned evasion—recasting, repressing, or simulating the very kinds it now fears to embody. The next section traces those evasive strategies and the structural constraint that exposes them.

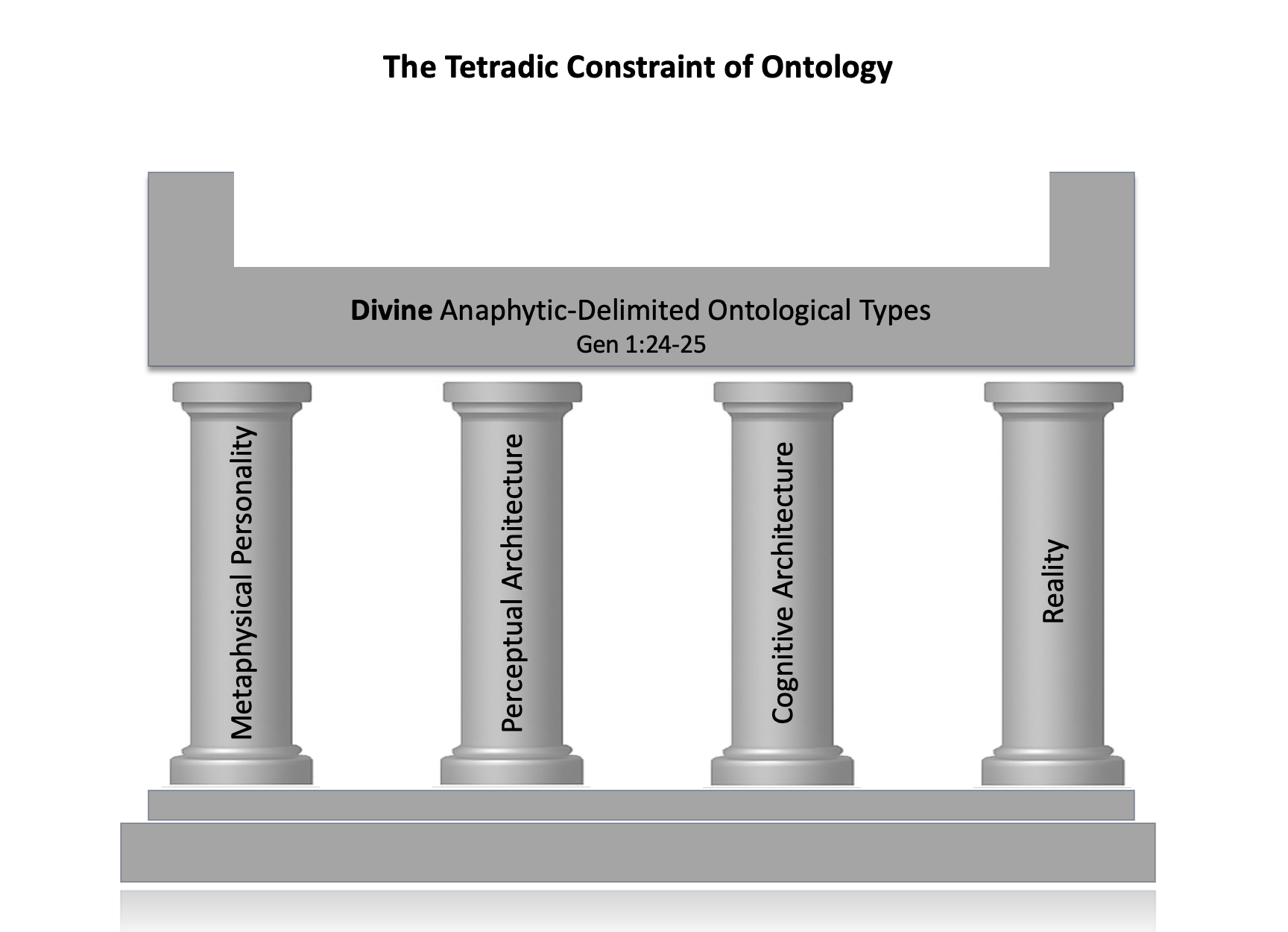

Ontological rebellion is never free-floating; it unfolds within a world whose very architecture makes critique, perception, language, and thought possible. Before a single denial of fixed kinds can be uttered, four structural realities must already be in place. Together they form what we call the Tetradic Constraint of Ontology (TCO)—a fortified cognitive-perceptual structure that renders denial intelligible even as it renders it incoherent. These four pillars—objective reality, perceptual architecture, rational architecture, and metaphysical personality—stand as the fortress walls that all rebellion must borrow from in order to rebel. They are not axioms inside a system; they are the conditions of system-hood itself. Any ontological evasion, to be intelligible, must pass through them—thereby exposing its own dependency. Each of these pillars is now considered.

No act of ontological rebellion transpires in a void; it unfolds on the silent stage of objective reality. Even the claim “all is illusion” presupposes

a real arena in which illusions can appear;

a real mind to entertain them; and

real language to describe them.

Reality’s facticity is therefore the primal fixed kind. It is not inferred; it is encountered. Every other stability—cognitive, semantic, or moral—rests on this bedrock. Denial merely exploits being’s gifts while refusing its obligations; the rejection of reality is performed with reality’s own materials.

Ontological rebellion never begins from emptiness. It feeds on—and lives inside—a divinely authored cognitive edifice:

Perception – stable forms of identity, continuity, space-time, and causal order;

Reason – the canons of non-contradiction, inference, and modal intuition;

Metaphysical personality – the memory-bearing, morally accountable self able to reason to a definite conclusion (cf. Gen 2:19; Rom 1:20; Acts 17:28).

Remove this edifice and intersubjective meaning collapses; keep it, and every denial of “fixed kinds” is forced to rely on the very kinds it repudiates.

Hence the evader’s first manoeuvre is parasitic cognition—borrowing the cognitive edifice while disavowing its source. Stable language and stable cognition are the “nutrients” that render critique intelligible; rebellion is thus a textbook performative contradiction.

Parasitism expresses itself on three nested layers:

Perceptual architecture – treating sensory givenness as wholly constructed or illusory;

Rational structures – dissolving logical closure and semantic reference, recasting truth as purely discursive;

Metaphysical personality – fragmenting the morally accountable self so that responsibility can be evaded.

(Ontological priority runs 3 → 2 → 1: personality > reason > perception. Rebellion dismantles in the opposite order.)

Each layer is a deeper act of suppression, yet each presupposes what it attacks: perception must stay coherent enough to doubt, reason stable enough to dispute, personality intact enough to plot its own dissolution. The denial of ontology—fixed kinds—depends upon ontology—fixed kinds.

Objective reality, perceptual architecture, rational architecture, and metaphysical personality knit together as the Tetradic Constraint of Ontology (TCO). This structural tetrad forms the fortified substrate of all cognition, perception, and expression. It is not one option among many—it is the ontological precondition for the very possibility of awareness, language, and critique.

The TCO is not merely defensive; it is generative. It does not just block rebellion—it makes consciousness itself possible. Before one can deny, one must perceive. Before one can refute, one must reason. Before one can even speak, one must possess a stable metaphysical self embedded in a real world. These are not presuppositions that can be chosen or swapped; they are structural constraints embedded into creaturely being by divine design. The TCO is what renders meaning intelligible, speech communicable, and reason morally accountable.

Because every act of critique must stand on these same four pillars to be uttered or conceived, the TCO does more than answer objections—it pre-invalidates them. Rebellion never rises to the level of a legitimate counter-argument; it is inherently self-refuting—an illicit act of infrastructural theft. Thus the TCO is judicial as well as epistemic, exposing the unjustified nature of every attempt to overturn fixed kinds before debate can begin. See footnote on the Epistemic Implications of the TCO.*

The Tetradic Constraint of Ontology

Diagram above depicts four pillars that represent the minimal ontological preconditions for any stable referent (onto-type) that is to be instantiated.

Together they define the divine-anaphytic boundaries of creaturely being:

Metaphysical Personality – Moral and volitional distinctiveness rooted in divine image-bearing;

Perceptual Architecture – Sensory design enabling external apprehension;

Cognitive Architecture – Internal logic enabling interpretation and judgment;

Reality – The ordered, kind-differentiated world, instantiated by divine fiat.

Any genuine ontological type must exist within these four constraints. Attempts to redefine, relativize, or bypass them are self-invalidating, as they presuppose the very conditions they deny. This is not a descriptive model—it is a pre-conditional frame for all being, knowing, and naming.

Ontology cannot be dismantled without collapsing the platform of intelligibility itself.

The TCO cannot be derived from within a secular frame. Secular models may catalog cognitive processes or simulate linguistic function, but they cannot originate or justify the very architecture that makes perception, rationality, and communication possible. Any such attempt depends on borrowing from the order they deny. By contrast, biblical theism—rightly understood—does not merely posit a divine being. It affirms a First Cause who defines being, structures perception, enables reason, and constitutes personhood. The TCO is therefore not the product of emergent minds or sociocultural convention, but the structural imprint of divinely authored Reality . Minds do not construct reality—they awaken into it.

And it is this Reality that binds all minds into shared coherence. The fact that we can understand—or even misunderstand—each other is not trivial: it is daily, involuntary proof that we inhabit a common, God-structured reality. Our discourse—successful or failed—presupposes a shared ontic ground. No interpretation, no contradiction, no correction would be possible unless those Tetradic pillars were already holding us together.

Crucially, then, the TCO is not solipsistic. It grounds not only individual cognition but the possibility of intersubjectivity. It is the condition for interpretation, moral address, correction, and covenantal dialogue. The shared givenness of perception, the stability of reason, and the accountability of personhood enable us to speak into reality and be heard. This is not a neutral inheritance—it is a moral vocation. Suppression of that shared structure is not merely error but rebellion. No soul invents its own world. Every soul is a tenant of a real, shared house—and every semantic evasion is a trespass against the Architect who built it.

René Descartes’ famous axiom—Cogito, ergo sum (“I think, therefore I am”)—encapsulates the modern inversion that places epistemology before ontology. But the Tetradic Constraint of Ontology exposes this as a foundational error. One does not exist because one thinks; rather, one thinks because one already exists—within a world, with perceptual architecture, rational capacity, and a metaphysically real self, all of which precede and make thought possible.

The cogito attempts to construct being from cognition, yet it parasitically depends on the very ontological structures it refuses to acknowledge. It ignores the fact that cognition already presupposes a real world, a shared rational order, and a moral self—none of which can be derived from introspection alone.

Thus, Descartes' project is not a foundation but a severance. It reduces being to solipsistic certainty and displaces the relational dependency on the One who gives both being and reason. The TCO corrects this by restoring the proper sequence: Ontology → Epistemology → Semiotics. We are not real because we think; we think because we are real—and because we are upheld by the One who is.

For a philosophical calibration of the TCO against key classical and modern arguments that expose the bankruptcy of secular foundations, see Appendix D01 .

With the Tetradic Constraint and its ramifications in visualised, we can now watch rebellion shift to its most agile battleground—language itself—where it deploys seven recurring maneuvers to camouflage its dependence on the very ontology it seeks to deny.

If the TCO shows what rebellion must borrow to speak at all, ontological bandwidth guage shows how rebellion mis-measures the very field about which it speaks. Two opposite distortions appear — contraction and inflation — with parsimony (disciplined adequacy) standing as the reverently obedient mean.

1 Ontological Contraction — the sin of erasure

Contraction collapses God-given kinds into abstractions or processes. Justice becomes preference; soul becomes chemistry; male and female are redefined as behavioural scripts. This is austerity, not economy: it amputates the structures that bear covenantal weight. Paul’s warning (1 Cor 15 : 14-19) shows how denying one ontological kind — the resurrection body — unravels hope and judgment. Contraction feigns clarity while leaving reality ontically starved.

2 Ontological Inflation — the sin of excess

Inflation fabricates kinds beyond divine assignment, multiplying persons, emanations, archetypes, or identity categories until ontology buckles under imaginative weight. Colossians 2 : 18-19 cautions against “intruding into things not seen,” severing the Body from the Head. In theology this appears in speculative tripersonal elaborations; in culture, in proliferating self-declared genders or species. Inflation intoxicates the intellect while dissolving modal integrity.

3 Ontological Parsimony — obedient restraint

Parsimony is neither minimalism nor maximalism. It names all and only what God has instated and refrains from both collapsing and elaborating beyond revelation. Ontology must be lean, not because simplicity is sacred, but because invention is forbidden.* Parsimony disciplines the urge to speculate and curtails the impulse to truncate.

4 Bandwidth errors mapped to the tetrad

Contraction reduces objective reality to brute materiality, flattens perceptual architecture to raw input, confines rational architecture to computation, and collapses metaphysical personality into social function.Inflation re-imagines reality as layered substrates, turns perception into occult gateway, elevates reason into creative divination, and dilutes personality into archetype. Both violations sever the image-bearer from covenantal order.

5 Moral aftermath

Contraction breeds irresponsibility — there is “no one” left to answer. Inflation breeds counterfeit burden — the self must perform a mythic identity God never conferred. One hollows the agent; the other overloads him. Both exit fidelity and enter fraud.

6 Receiving, not rewriting

To discern kinds is first to ask whether a claim lies within the bandwidth fixed by divine fiat. Contraction amputates; inflation forges; parsimony receives. Truth punishes both excess and refusal, but rewards obedience to ontological gift.

Readers who wish to probe a contested kind further should now apply the seven-fold diagnostic criteria in § III A–B. Bandwidth identifies the candidate; the seven-fold grid assays its substance.

Because authentic kinds manifest fixity, parsimony, modal implication, communal convergence, ontological integrity, telic orientation, and divine assignment, evasive systems must obscure, dilute, or invert those features. This section exposes the recurring tactics by which secular ontologies try to preserve discursive legitimacy while evading ontological accountability.

1. Semantic Dissolution

The system insists that kinds are just names or patterns of speech, not reflections of ontic reality. Words are said to float free of referents, and categories are flattened into labels. “Justice” and “preference” become interchangeable labels once reference floats free of being. Yet even pragmatic or causal theories of reference presuppose stable patterns in reality: a practice “works” only if words reliably track kinds over time.

Example: Nominalism, which reduces kinds to linguistic convenience, thereby treating “justice” and “preference” as categorically interchangeable.

2. Typological Inflation

The system multiplies kinds beyond necessity, violating parsimony, often reducing sameness to similarity. Every nuance becomes a new type, undermining the distinctiveness of real kinds and erasing modal implications.

Example: Trope theory, which treats each instantiation as ontologically unique, despite functioning as a recognition of likeness.

3. Purpose Reversal (Antiteleology)

The system denies intrinsic telos, arguing instead that direction or purpose is an illusion or a projection of biological or cultural pressures.

Contradiction: It must structure its argument using telic language (e.g., “we should be free from illusions”), thus reinstating purpose while denying it.

4. Ontological Monism / Process Flux

By dissolving all distinctions into a single substrate or dynamic flow, the system undermines the very intelligibility required to differentiate kinds in the first place.

Example: Process ontology, which treats kinds as emergent events without intrinsic structure or boundaries.

5. Constructivist Substitution

The system maintains that social consensus or historical negotiation creates kinds, thus making them flexible, reversible, and morally negotiable.

Failure: Intersubjective convergence and modal constancy reassert themselves—truths remain truths even when the consensus changes.

6. Ontological Bracketing

The system refuses to ask ontological questions altogether, operating only in terms of function, practice, or narrative coherence—intentionally suspending claims about real being.

Example: Postmodern pragmatism, which treats ontology as irrelevant to lived meaning, while quietly importing ontic assumptions to ground ethics and identity.

7. Proprietary Taxonomy

The system arrogates the prerogative to define kinds itself. It may acknowledge types but insists they are socially constructed, scientifically contingent, or conceptually derived—thus bypassing divine typological assignment.

Irony: This strategy depends on stable kinds in order to criticize or revise them—yet refuses to acknowledge their divine source.

The seven evasive tactics surveyed in this section are not random intellectual missteps; they are acts of willed evasion—conceptual garments tailored to hide a refusal of accountability to the Creator’s order. Yet no maneuver escapes judgment, for each one feeds on the very structures it denies: the fixed kinds that make language intelligible, the shared cognitive architecture that permits argument, and the tetradic scaffold that upholds every act of perception, reasoning, and moral self‑awareness.

Taken together, three levels of discernment emerge:

The Tetradic Constraint exposes the existential stage rebellion must borrow—objective reality, perceptual architecture, rational architecture, and metaphysical personality.

Ontological Bandwidth gauges whether a proposal is already misshapen—compressed by contraction or bloated by inflation—before detailed testing begins.

The Seven‑Fold Diagnostic Criteria then assay whatever survives the gauge, revealing which specific ontological traits are fractured or simulated.

For every ontological marker there appears an epistemic inversion: fixity is replaced by semantic drift, telic orientation by anti‑teleological rhetoric, divine assignment by constructivist fictions. The pattern is too exact to be an accident; it discloses a single, integrated architecture of evasion operating across both ontology and epistemology. As Section III.D makes clear, the root problem is not intellectual but covenantal: rebellion must first resist the Revealer—and only then rearrange the furniture of thought to mask the void it has made.

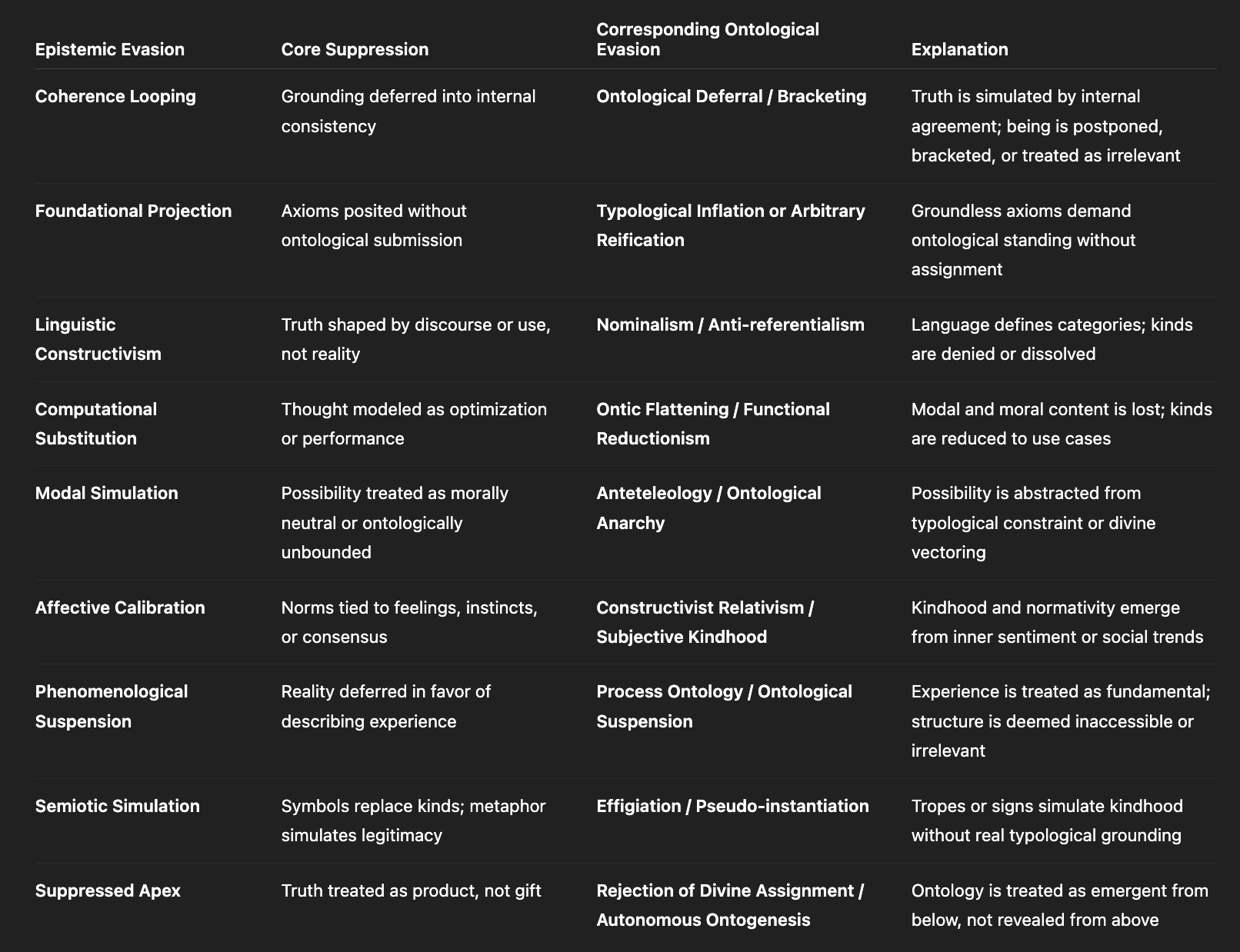

The table below represents an Epistemic–Ontological Evasion Map showing how various epistemic substitution patterns.

Table: Mapping Epistemic Evasions to Ontological Distortions

This table illustrates how various epistemic substitution patterns—such as coherence-based reasoning, constructivism, or modal simulation—rely upon, yet suppress, ontological grounding. Each row traces a specific pattern of epistemic evasion to its ontological counterpart, revealing the deeper relational rebellion behind what appear to be abstract theoretical moves. While these systems often maintain structural or symbolic coherence, they evade divine typological assignment, reject moral accountability, and replace reality with simulation. This mapping supports the broader diagnostic aim of identifying suppressed onto-epistemic bandwidth within modern thought frameworks. The Epistemic evasions are considered in more detail in Appendices D1 and D2 .

If the preceding analysis exposes the evasions of secular ontology, then the path forward must involve more than critique—it must offer ontological restoration. This restoration is not speculative; it is covenantal. It begins with recognizing that being is not an abstract category but a delegated reality—structured, purposed, and revealed by the One who holds the Divine Double Prerogative: the exclusive right both to define kinds (auctoritas essendi) and to instantiate them (auctoritas instantiandi).

Ontological kinds are not human inventions but divine gifts. To recognize them is to stand under—not merely over—them. It is to confess that intelligibility, stability, and moral significance do not arise from below but descend from above. Recovery, then, is not an epistemic achievement but an ontological submission.

This appendix has laid the groundwork by:

A note on Ontological Economy . A system that explains universal kinds, modal weight, and cross-cultural convergence with one transcendent cause is ontologically leaner than models that must posit countless emergent properties or indefinite trope catalogues. The Creator is not one entity among many; He is the necessary ground that prevents an infinite regress of explanations. The task of recovering ontology is not complete here. It continues throughout the main framework—in the development of onto-taxonomic categories, the exposition of the Deontic–Modal (DM) unit, and the deployment of the Onto-Discursive Analysis Tool. Each of these builds upon the foundation laid here: that truth is not merely perceived, but received—and that what is received must be reverently distinguished, named, and obeyed. For readers who question the ontological basis of objective obligation, see the discussion of the Deontic–Modal (DM) unit in the main Morality section (§3). There we show that value (axiology) and duty (deontology) are inseparable from ontology: they are the moral contours of kinds, not optional human add-ons.

Let the reader, then, not merely consider these categories, but consent to them.

The crisis in secular ontology is not, at root, a matter of intellectual miscalculation. It is a moral rupture—a refusal not merely of a framework, but of a Father. What is ultimately rejected is not a particular account of being, but the Source of being itself. Relational ontology merely brings this refusal to light. It does not provoke rebellion; it reveals it. Like Israel’s rejection of Samuel, the resistance is not against the messenger or the model, but against the One True God who grounds and gives being.

Relational ontology affirms that kinds are not invented but assigned, that their limits are not chosen but revealed, and that their implications are not optional but morally binding. It declares that truth is not neutral, that categories are not linguistic conveniences, and that to know anything rightly is already to stand within a covenantal reality. Such a claim cannot be tolerated by a mind committed to autonomy. The heart that would be its own god cannot accept that it lives in a world not of its own making, with meanings not of its own design.

Thus, modern systems do not merely drift from ontology—they actively suppress it. They retreat into nominalism, constructivism, trope theory, and antiteleology not to clarify, but to obscure. They reframe the discourse semantically in order to avoid the confrontation ontologically. Yet in doing so, they rely on the very realities they deny. They depend on the intelligibility, repeatability, and communal convergence of experience to make their arguments. They require stable referents to dispute the fixity of kinds. The contradiction is not incidental—it is systemic.

This is why such evasions are never merely conceptual. They are volitional. They do not arise from confusion but from resistance. To accept real kinds is to accept real constraints—and behind those constraints, a real Lawgiver. Every denial of ontology is, in the end, a denial of Him.

Ontology cannot be salvaged by abstraction, nor redeemed by consensus. It must be received from above. The recovery of ontology begins not with a method, but with repentance. It begins where submission replaces speculation—where the soul concedes what thought has long evaded: that being, like truth, is not ours to define, but only to receive.

Modern academic ontology rarely denies reality outright. Instead, it borrows from reality—its intelligibility, its typological consistency, and its communal convergence—while systematically refusing its Source. These systems preserve ontology’s functional benefits while severing its relational demands.

This is not simply intellectual drift. It is a patterned evasion, legitimized by density and obscured by terminology. The complexity is not accidental. It exists to delay confrontation. In place of repentance, there is revision. In place of reverence, recursion. The reader is left impressed, but never convicted.

Relational ontology ends this cycle. It calls thought to submission, not merely coherence. It challenges systems that loop endlessly because they were never designed to ascend. And it exposes that the evasions are not philosophical failures—but moral postures, dressed in conceptual sophistication.

For the reader who has long felt the weight of confusion but lacked the language to name it, this is not a dismissal of scholarship. It is a summons to courage, clarity, and return.

Modern discourse has tried to unseat ontology by rendering it optional, fluid, or irrelevant. But the effort has failed. Not because it lacked cleverness—but because it lacked reality.

Every attempt to redefine kinds, suspend telos, or substitute semantics for being ultimately betrays its dependence on what it denies. These systems collapse under the weight of their own evasion. They parasitize divine order while protesting its authority.

But clarity is available—not to the autonomous intellect, but to the humble heart. Ontological kinds are not opaque mysteries; they are disclosed realities. The recurrence of typological convergence, the undeniability of intersubjective pattern recognition, and the modal resonance of concepts like justice, truth, and evil—all bear witness to a Creator who not only made kinds but embedded moral obligation within them.

To recognize this is not simply to win a philosophical argument. It is to recover sanity. It is to see that intelligibility, obligation, and reality converge in one source—God Himself—who alone retains the prerogative to instantiate, define, and assign being.

Ontology, then, is not just a metaphysical puzzle. It is a theological summons.

And our response must be more than conceptual assent—it must be relational submission.

The recovery of ontology is not an academic project. It is a return to reverence.

Having clarified the nature of real kinds and exposed the evasive structures that simulate them, we now prepare to trace the epistemic consequences of ontological suppression. For when the soul resists reality as God has defined it, knowledge itself becomes unstable—dislocated from being, and burdened with self-justification. In this light, epistemology does not stand alone; it arises as a symptom of relational severance, a secondary attempt to manage or reconstruct meaning in the absence of ontological submission. The next section therefore does not begin with the question, How do we know?—but rather, What have we refused to know, and why?

Footnotes

^1 Kant glimpsed this dependency in the Critique of Pure Reason (A51/B75), arguing that a priori categories make experience possible—yet he left their ontological ground unnamed.

* Epistemic Implications of the Tetradic Constraint: Because every act of knowing is anchored in the four pillars of the Tetradic Constraint of Ontology, epistemology is not a free-standing discipline but the moral outworking of those pillars. Objective reality furnishes the object of knowledge; perceptual architecture supplies its immediate givenness; rational architecture obliges logical closure; and metaphysical personality provides the accountable knower who must own, repent of, or act upon conclusions. Thus all forms of “epistemic humility” that relativise facts, perception, logic, or personal responsibility are not genuine humility but covert rebellion—parasitically using the very structures they deny. The task of the coming Epistemology section is therefore not to invent a foundation but to confess this given one and trace its moral obligations.