This appendix is not a conventional history of theology. It is a diagnostic retrospective—measuring fidelity not by institutional continuity or doctrinal confession alone, but by the preservation (or suppression) of the relational, typological, and covenantal structure through which the One True God has ordained truth to be known. It does not deny that real doctrine was confessed, or that real believers were faithful. But it insists that without the recovery of ontological submission, such fidelity risks being constrained to closed systems that cannot ascend. The purpose of this trajectory is not condemnation—but clarification: to show why modern theological and philosophical thought cannot resolve its crisis without confronting the suppressed structure it has inherited.

The purpose of this appendix is not to recount theological milestones, doctrinal evolutions, or ecclesiastical events in a conventional historical sense. It is instead a diagnostic tracing—a strategic examination of where and how ontological submission was displaced over time. It asks not simply what the church taught, but what it permitted itself to know, and how it positioned itself in relation to God's prerogative to define reality.

Fidelity Beyond Doctrine. Theological fidelity is often measured by creedal assent: Does a tradition affirm the deity of Christ? The atonement? The resurrection? These questions matter—but they do not exhaust faithfulness. Fidelity to God is not merely doctrinal—it is ontological. To affirm Christ while distorting the created structure by which God defines kinds, appoints typologies, names realities, and grounds moral obligation, is to introduce epistemic rebellion beneath theological orthodoxy. It is possible to affirm the right things within a distorted structure of reality, and thereby undercut the very truth one claims to uphold.

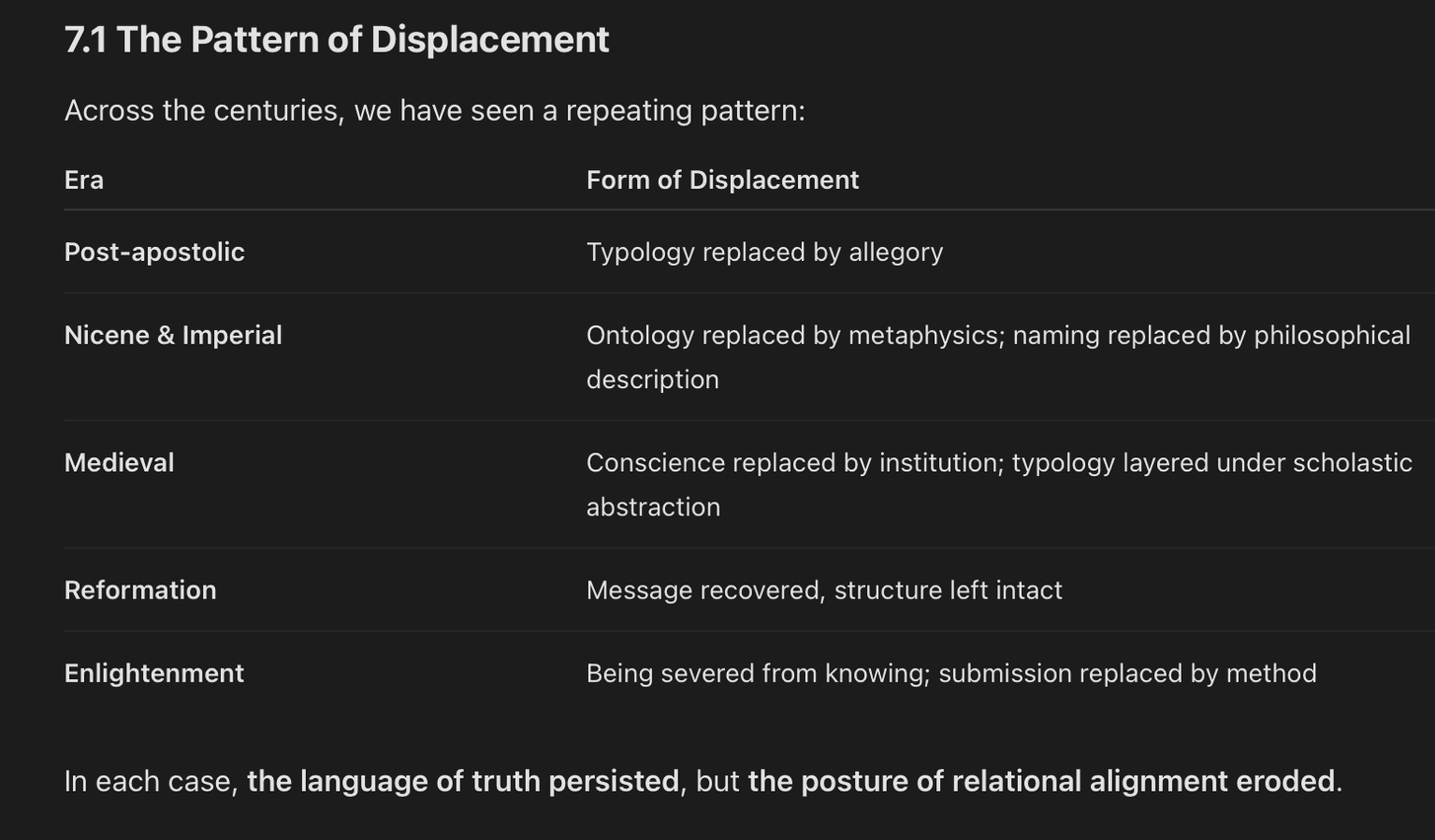

Throughout church history, even where the gospel was preserved in part, the ontological framework necessary to preserve it faithfully was not. The drift was subtle, then codified, then internalized:

Over time, the epistemic posture of submission—which is the condition for discerning reality—was substituted by systems of mediation, speculation, and symbolic abstraction.

This appendix will trace key historical moments—from the apostles to the Reformation—not to assign blame, but to map the trajectory of displacement.

We will see that:

The current philosophical and theological crisis is not a modern invention. It is the final flowering of an ontological suppression that began not with reason, but with religion. The task of this framework is not only to reclaim epistemology and ethics, but to restore reality itself—and that requires confronting how and when it was lost.

Typology, Moral Posture, and Relational Ontology in the Early Church

The apostolic period represents the last sustained moment in the theological record where ontology, epistemology, and relational posture remained structurally unified. In contrast to both the philosophical abstractions that would follow and the later doctrinal formulations that would flatten meaning into metaphysical categories, the apostles spoke of reality in terms that were covenantal, typological, and personally accountable.

They did not speculate about being. They responded to it.

The apostles—particularly Paul and John—operated with an ontology that was:

They did not ask what “truth” or “being” was in abstraction. Instead, they understood:

This was not mysticism, and it was not philosophical speculation. It was response to revealed ontology—to a world already structured, already named, already judged by the presence of Christ.

The early preaching and writing of the apostles revealed a commitment to typological order:

The apostles did not use language to create meaning. They used language to respond to a reality that was already laden with meaning.

They believed not only in the truth of Scripture, but in a world structured by the same Logos who authored it.

Paul speaks of the conscience as something that:

This is not psychology—it is ontology. The conscience is not a mechanism of feeling; it is a moral receptor calibrated to typological reality. Its purpose is to recognize and align.

Thus:

For the apostles, Christ is not merely a redeemer—He is the epistemic and ontological apex: “In Him are hid all the treasures of wisdom and knowledge.” (Col. 2:3) “He is before all things, and by Him all things consist.” (Col. 1:17). This is not theological poetry—it is ontological declaration.

The early church understood this intuitively—before the categories became abstract, systematized, and detached.

The apostolic moment was not a golden age of doctrine. It was a moment of structural integrity—before conceptual fragmentation set in. Ontology, conscience, epistemology, typology, and moral alignment were one seamless reality, grounded in the person and work of Christ. What followed would not primarily be rebellion against this truth—it would be a drift, a subtle dislocation of categories, and a progressive redefinition of how reality could be known, structured, and named.

The early post-apostolic church did not immediately rebel against truth. It did not discard Scripture, deny Christ, or reject moral seriousness. But it subtly dislocated the ontological structure that undergirded biblical revelation—beginning a drift that would define the centuries to follow.

The move was not from truth to error, but from ontological submission to conceptual mediation. From typological recognition to allegorical displacement.

The apostolic use of typology assumed that God defines kinds—and that history, categories, and persons are embedded within a divinely structured pattern of meaning. Typology was:

In the early patristic period, however, typology began to erode under pressure from: philosophical reinterpretation, especially under Platonic influence; polemic needs to establish continuity with the Old Testament while avoiding Jewish literalism; and the drive to find deeper or “spiritual” meanings within Scripture.

Thus, typology became allegory:

Where typology submits to what God has structured, allegory rearranges what God has revealed.

Simultaneously, Gnostic movements redefined being itself. They reframed reality as a hierarchy of emanations or dualities:

This system displaced ontology in two key ways:

Though the church resisted Gnostic doctrines, many of its structural reflexes persisted: A\a tendency toward mystical abstraction;a division between outward forms and inward meanings; a hierarchical approach to knowledge that undermined moral accessibility.

As Scripture became increasingly interpreted through conceptual filters—whether philosophical, mystical, or moralistic—the church’s posture toward truth changed. Where the apostles received and declared what was revealed, the early fathers increasingly: mapped, layered, and harmonized divine truths within external conceptual systems; treated revelation as material to be elevated through meditation, speculation, or ecclesial authority; reoriented theology around exegesis by analogy, rather than typological fidelity.

This marks the beginning of epistemic mediation: Where knowing is no longer primarily relational submission to reality, but the interpretive construction of meaning within layered systems.

Though many early theologians were sincere and brilliant, their categories were already drifting from biblical ontology. The result was: a weakening of typological clarity; a proliferation of layered meanings; and a foundational shift from truth as confrontation to truth as interpretation. The allegorical habit formed the mental architecture that would later house scholastic speculation, sacramental absolutism, and institutional control. The ontology of Scripture—grounded in creation, covenant, and Christ—was never formally denied. But it was gradually overwritten, not by contradiction, but by accumulated re-framing.

This early shift was not rebellion—it was reverence without submission. But the effect was the same:

The next phase would not correct the drift. It would canonize it.

Doctrinal Precision Without Ontological Submission

The Council of Nicaea (A.D. 325) is often viewed as a decisive victory for orthodox Christology— but beneath this alleged doctrinal clarity lay a deeper and largely unacknowledged cost: ontological categories used to defend truth were no longer derived from revelation, but from Hellenistic metaphysics. And the ontological framework of the Hebrew Scriptures—rooted in divine naming, typological structures, and covenantal categories—was systematically displaced.

This moment marks the beginning of a formal shift:

The Council of Nicaea rightly opposed:

It affirmed that:

This was a necessary defense of the faith—but the categories used were non-biblical in origin. The ontology of “ousia” and “hypostasis” was not revealed. It was borrowed—from Greek metaphysics, not divine taxonomy.

By adopting Hellenistic metaphysical terms, the church committed what this framework calls a category error of instantiation:

The result was a simulation of typological fidelity—terms that gestured toward truth, but which lacked ontological warrant from God’s self-disclosure.

To describe Christ as “light from light” is poetic; To define Him as “essence from essence” is ontological extrapolation.

The displacement of biblical ontology did not begin with Nicaea. As early as the second century, Emperor Hadrian’s anti-Judaic policies—including the banning of Torah observance, Sabbath-keeping, circumcision, and Hebrew identity—had already begun to suppress the categories and covenantal grammar through which divine ontology was originally disclosed.

By the time of Constantine, these pressures had crystallized into formal ecclesiastical policy. The Roman church, newly aligned with imperial power, codified an overt severance from Hebraic categories and instituted a theological identity that treated the Old Testament not as the ontological foundation of reality, but as a symbolic prelude to ecclesiastical authority.

The effects were profound and structural:

The loss was not merely linguistic or cultural—it was ontological. The grammar of reality was rewritten without divine warrant.

By the time Nicaea defined the Son as homoousios with the Father, the ecclesial imagination had already replaced biblical ontological submission with imperially sanctioned metaphysical control. The church affirmed Christ—but no longer in the categories by which God had revealed Him.

With imperial backing, the church became institutionally necessary for access to truth:

This marks the moment when onto- epistemic posture was displaced by ecclesial procedure.

Truth was no longer received through submission—it was administered through systems.

The apex of the ontological cone was reserved for the priestly class—and increasingly defined by categories God never authorized.

Ontological precision was claimed, but at the cost of ontological permission.The apex was verbally confessed, but structurally appropriated and occluded. The language of fidelity remained, but the logic of relational submission was displaced—intentionally—by systems of conceptual mastery. This was not an innocent drift, but a deliberate reconfiguration of how truth was accessed—replacing divine invitation with ecclesial control. It laid the groundwork for a scholastic edifice that would preserve theological terminology while operating in a dislocated ontological architecture, foreign to the relational logic of Scripture.

Layered Complexity Without Typological Permission

Following the Nicene period and into the medieval centuries, Christian theology underwent a profound transformation—not in the object of its devotion, but in the structure of its reasoning. The truth of God was still confessed, but the method of engaging that truth shifted decisively. Theology became a system, and ontology became an architecture of abstraction layered on abstraction.

The result was what this framework diagnoses as ontological inflation: the multiplication of categories, distinctions, and terms without corresponding typological warrant from divine revelation. As the system expanded, so too did the distance between God’s categories and man’s.

Medieval scholasticism—typified by figures like Anselm, Aquinas, Bonaventure, and Duns Scotus—sought to systematize theology with philosophical rigor: God’s nature was described in terms of actus purus, substance, essence, simplicity, form, final cause, and so on. Created reality was defined through chains of causation, categories of being, and distinctions between potency and actuality. These terms were not evil. But they were extra-biblical, and their use eclipsed typological alignment. What had once been moral recognition of kind and covenant became metaphysical classification under human management.

The scholastic habit layered distinctions in ways that eventually simulated ontological clarity while displacing it:

Essence vs. existence: Treated as separable in creatures, unified in God.

Substance vs. accidents: Used to explain sacramental transformation (e.g., transubstantiation).

Form vs. matter: Applied to humans, angels, sacraments, and divine action.

Each distinction carried internal logic—but lacked typological origin. That is, they were not grounded in categories God had revealed; they were deduced, imported, or synthesized. Thus, the scholastic system simulated typology through precision—but lost ontological submission in the process.

As metaphysical precision increased, language began to decouple from referent:

“Grace” was no longer first a relational gesture—it became a created substance infused into the soul.

“Faith” became a disposition or habitus, categorized and layered rather than lived.

Sacraments were explained through mechanistic metaphysics rather than typological fulfillment.

Words retained form but lost their function as pointers to covenantal reality.

This is what the broader framework elsewhere calls semiotic drift: when signs circulate within closed systems of meaning and cease to confront the conscience with ontological weight.

Alongside ontological inflation came a subtle but decisive shift in the location of epistemic authority. As the scholastic system grew in complexity and metaphysical layering, the church increasingly positioned itself as the necessary interpreter and administrator of truth. Knowledge of God was mediated through clerical hierarchy. Typological discernment was outsourced to institutional offices. Conscience was no longer the inner seat of relational encounter, but was subordinated to external sacramental cycles and canonical prescription. This was not merely a pastoral adjustment—it was a structural displacement of direct moral accountability. The soul was no longer addressed directly by God through revealed categories. It was managed—processed through epistemic bureaucracy disguised as liturgy and sacrament.

Grace was infused through sacramental channels. Justification became sequenced and quantified. Holiness was tied to status, office, or sacramental participation—rather than typological conformity to Christ. This amounted to an ontological capture of the believer’s access to reality. One could not know or discern rightly except through participation in the institutional system. The result was epistemic infantilization: the soul could not ascend because it was not permitted to think independently.

What had once been the apex of covenantal alignment—truth confronting the individual soul—was replaced by: doctrinal fidelity as ecclesiastical loyalty; epistemic submission as institutional compliance; discernment as liturgical repetition. In other words: the church became the simulated apex—standing in the place of typological fidelity while suppressing direct access to the One who defines being. This was not merely an abuse of power. It was ontological interposition.

The very structure of this system began to produce internal pressure—moral dissonance, theological frustration, and philosophical fatigue. These would later erupt in the Reformation, and even more explosively in scientific resistance, which would seek access to reality by circumventing the very institution that had once claimed to safeguard it.

The tragedy is not that the church failed to teach. The tragedy is that it redefined access to truth as submission to itself—and thereby buried the epistemic posture of submission to God.

The scholastic system achieved conceptual brilliance but spiritual displacement. It expanded vertically, adding layer upon layer of distinction. But it ceased to ascend morally, because it no longer confronted the soul with typological categories that demanded submission. In its place stood a simulated ontology—one that defined, organized, and explained all things except the structure of relational knowing that leads to the apex. The Reformation would rise in protest—but even it would inherit much of this displaced architecture.

Gospel Clarified, Structure Unreformed

The Reformation was a pivotal rupture in church history. It reclaimed foundational truths long buried beneath ecclesiastical overreach and scholastic layering: justification by faith, not institutional merit; scriptural authority, not magisterial infallibility; the priesthood of all believers, not hierarchical mediation. But beneath these recovered doctrines remained an unchallenged ontological framework—a conceptual structure still shaped by the very metaphysical assumptions and hierarchical reflexes the Reformers sought to oppose. The Reformers broke the pipeline, but not the blueprint. The result was soteriological liberation within the established metaphysical captivity.

The Reformation achieved real and lasting theological recovery: the conscience was reawakened as the site of moral accountability before God. The Word of God was restored to primacy in language, accessibility, and authority. Grace was declared to be unmerited, direct, and covenantally offered. These were not abstractions—they were relational and ontological corrections at the level of lived reality. But the structural categories that supported those doctrines were still inherited from the late-medieval system.

Despite the Reformation’s theological fire, it retained much of the scholastic scaffolding: essence, substance, and nature continued to dominate discussions of God and man. Biblical categories like “kind,” “clean/unclean,” “holy/profane,” and “image of God” remained underdeveloped or recast through preexisting metaphysical frames. Even the concept of “faith” was often systematized as an intellectual act, rather than a typological alignment of personhood to the covenantal truth of Christ. The soul was now free—but its epistemic posture remained underdefined, and the relational ontology of Scripture remained only partially recovered. In effect, the Reformation restored theological substance but left the ontological-epistemological hierarchy unrepaired. While it recovered the authority of Scripture and the centrality of grace, it did not recover the deeper ordering of truth: that ontology grounds epistemology. This failure left in place what we here name the onto-epistemic disconnect—a structural rupture in which knowledge continued to develop without being re-anchored in relational ontology. The result was an unintended continuity: a new theology built with inherited categories, a liberated conscience operating within scholastic architecture, and epistemic tools functioning independently of ontological submission.

While the Reformers rightly challenged doctrinal corruption and institutional abuse, they did so within the conceptual and semiotic constraints of the intellectual world they inhabited. The dominant metaphysical vocabulary—terms like essence, substance, accident, and nature—had already absorbed centuries of ontological distortion.

And so, even as they recovered theological motifs like justification and grace, they remained largely confined within the Overton Window

of permissible categories. This meant their reforms were framed within misaligned language, and therefore often inherited the very ontological assumptions they sought to overturn.

In many cases, the reform was lexical but not structural: retaining borrowed terminology while unintentionally reinforcing the conceptual drift embedded within it. In short, the Reformation often reinscribed semiotic misalignment, even as it challenged institutional error.

While rejecting Rome’s sacramental system, many Reformers: retained a forensic/legal framing of salvation that, while doctrinally faithful, often suppressed the ontological transformation of regeneration. Continued to interpret Scripture within the same logic of proof-texting and propositional deduction used by scholastics—rather than recovering the typological and ontological imagination of the prophets and apostles. Preserved church confessions and catechisms that became functionally creedal, reinstituting a mediated mode of epistemic control—albeit without the sacerdotal layer. Thus, the Reformation redistributed access, but did not fully reform the structure by which reality was to be known.

The Reformation’s rejection of institutional epistemic control also planted the seed of a deeper rebellion—one it did not intend, but could not prevent: by elevating Scripture without recovering ontology, it allowed others to treat Scripture as text without structure. By rejecting institutional mediation, it created the intellectual permission to bypass revelation entirely—to pursue truth “directly,” without moral submission. By failing to restore typological categories, it left reality open to being re-described by emergent disciplines (science, philosophy, politics) using their own terms. In liberating the conscience, the Reformers reawakened moral awareness—but they did not re-anchor being. In challenging ecclesiastical authority, they paved the way for epistemic autonomy—both righteous and rebellious.

The Reformation recovered the message of salvation, but not the ontological grammar in which that message was originally disclosed. The apex was once again declared open—but the path to it remained fogged by old categories. The conscience was reclaimed—but typological clarity was not reestablished. The soul stood before God once more—but without the ontological scaffolding needed to sustain a covenantal epistemology. The next movement would not be reform—but revolt.

With the Reformation's protest behind and its incomplete ontology unresolved, the stage was set for a more radical dislocation: the formal and philosophical severing of knowing from being.

The Enlightenment, often seen as a triumph of reason over superstition, was in reality a revolt against mediated access to truth—but also a refusal to restore relational submission to ontological reality. The response to ecclesiastical overreach was not covenantal recalibration, but epistemic autonomy masquerading as progress.

Enlightenment thinkers sought liberation from the church—but they did not return to God. Instead, they created closed systems of thought designed to simulate truth without submission.

The Enlightenment emerged as an explicit resistance to: the institutional control of knowledge by the Church; the sacramental monopolization of grace and truth, and the metaphysical excesses of scholastic theology. Figures like Descartes, Locke, Hume, and Kant did not merely disagree with theology—they believed that epistemic integrity required detaching from its categories entirely. But rather than returning to a covenantal model of relational knowing, they adopted autonomous, abstract, or empirical alternatives. The ontological apex was no longer forbidden—it was now declared nonexistent.

The defining feature of Enlightenment thought is this: knowledge was redefined without reference to being—specifically, without reference to kinds. Truth was recast as internal coherence, empirical repeatability, or categorical necessity. Three dominant trajectories emerged: empiricism (Locke, Hume)—truth as sense data, observation, and verification; rationalism (Descartes, Leibniz)—truth as what can be deduced from self-evident axioms; and idealism (Kant)—truth as structured by the mind’s categories, limited to what can be known, not what is. Each model retained epistemic structure but severed ontological submission: the conscience was bypassed. Typology was erased. Revelation was bracketed or dismissed. The Enlightenment did not recover reality—it redefined access to it in order to avoid the necessity of moral alignment.

The key to Enlightenment thought was not merely disbelief—it was methodological suppression: reality could still exist, but only what was testable, observable, or inferable was valid. Moral categories could be discussed, but only if they were derivable from reason or utility. Religious truth could be tolerated, but only as private meaning, not ontological disclosure.

This birthed the epistemic posture of neutrality: the presumption that truth can be approached without relational posture; that all knowers can reason equally, regardless of alignment to divine order; that truth is a human achievement, not a moral confrontation. This is the modern inversion: truth no longer judges the thinker. The thinker now judges what counts as truth.

The reformers, though sincere in their challenge to doctrinal error, remained semiotically confined. They spoke within the linguistic and conceptual boundaries of their age—trapped within what today might be called the Overton Window of late medieval theology and emerging rationalist categories. As a result, they did not reconstruct the ontological architecture; they simply translated many of its assumptions into more palatable forms.

This was not a failure of courage, but a failure of semiotic discernment—and it ensured that the deeper relational-ontological rupture remained intact, paving the way for epistemic autonomy to be institutionalized as method.

Modern science emerged as a double-edged phenomenon: on one hand, it rightly rejected ecclesial control over investigation. On the other hand, it implicitly replaced submission with control. Nature was no longer a created order to be discerned typologically. It became: a mechanism to be explained; a system to be predicted; a field to be harnessed.

Scientific reason became epistemic conquest—truth through mastery, not alignment. While individual scientists retained theological belief, the structure of science became inherently non-relational: it neither required nor permitted typological categories. It operated without reference to moral posture or divine prerogative. Modern science thus continues in a state of ontological inertia: it advances by technical refinement and procedural recursion, but never reassesses its foundational posture. It remains in motion, not because it is grounded, but because it is unwilling to stop and ask what reality is, and to whom it belongs. Its power grows—but its capacity for typological discernment and moral orientation remains structurally suppressed. Thus, science became the final fruit of suppressed ontology: a system for describing reality that cannot tell you what anything is—only how it behaves.

The Enlightenment did not resolve the crisis of knowing. It codified it. It reacted against the errors of the church without recovering the structure of submission. It severed epistemology from ontology, creating systems that can generate predictions but not discern truth. It institutionalized epistemic neutrality, which functions not as fairness, but as methodological exile from God. This was not progress. It was recursion—the repetition of suppressed ascent within increasingly complex but ontologically severed systems. The Enlightenment did not remove God from the mind. It removed the posture necessary to know Him.

A Structure Lost, A Crisis Repeated

The historical trajectory from the apostolic era to modernity is not a simple story of truth versus error. It is the story of a progressive structural displacement—a slow but deliberate detachment of the knowing soul from the ontological framework that God instituted for truth to be encountered, discerned, and submitted to.

At every major juncture, elements of the gospel were retained. But the structure that gives the gospel its ontological clarity and moral weight—that defines kinds, anchors meaning, and binds conscience to truth—was gradually overwritten, reframed, or suppressed.

Doctrinal fidelity, liturgical reform, or methodological rigor are not enough. The crisis at every stage has not been primarily about content, but about posture: who defines reality? Who names categories? Who holds the prerogative to instantiate kinds? And who must submit to this structure? The failure to recover this divine prerogative has led each era to recycle the same evasions—under new terms, in new systems, with new vocabularies, but the same refusal to ascend.

The Conical Cognition model (Appendix D ) presented earlier can now be seen as historically mapped: the cone’s base was preserved in Scripture. The narrowing process was suppressed by institutional control, speculative metaphysics, and procedural autonomy. The apex was either claimed illegitimately (by the church), confined to the intellect (by the Reformers), or denied entirely (by modernity). Truth has not been destroyed—but the path to it has been buried under centuries of structural recursionand epistemic fragmentation.

This framework is not calling for nostalgia or creedal retrenchment. It is calling for: the restoration of ontological submission; the recovery of typological clarity; the confrontation of the conscience; and the moral realignment of epistemic posture toward the One who defines reality. The structure must be recovered—not just the content. We do not need a new theology. We need a restored way of knowing—in which the apex of truth is again accessible, but only by relational fidelity.

It is appropriate to acknowledge several critiques that may arise from this historical analysis. The following responses clarify the intention, method, and scope of this appendix:

1. “This is theologically motivated revisionism.”

This appendix is not a neutral church history. It is a theologically motivated analysis that examines fidelity through the lens of ontological submission, not institutional continuity. The framework is transparent in its evaluative criteria: alignment with God’s revealed structure for naming, typology, and epistemic access.

2. “It undervalues the theological good of past eras.”

This work affirms the doctrinal recoveries and moral seriousness of each era. But it argues that truth, once abstracted from the ontological grammar God has ordained, becomes vulnerable to distortion—even when sincerely preserved.

3. “Greek metaphysical categories were providentially useful.”

They may have been linguistically useful—but the core issue is ontological displacement. Utility does not grant divine warrant. Categories not disclosed by God cannot replace those that are. Their use, however serviceable, introduced a structural cost that is still being paid.

4. “This is too radical to be constructive.”

Radical only in the biblical sense: returning to the root. This critique arises precisely because the framework exposes the assumed neutrality of inherited systems. The goal is not destruction—but the recovery of the posture that permits theological and philosophical ascent.

The historical analysis presented here does not call for a return to any one era, doctrine, or institution. It calls instead for a return to the posture that was lost—the posture of ontological submission to the God who defines reality, names categories, and binds the conscience through revealed typology. Until that structure is recovered, theological fidelity will remain suspended in partial systems, and philosophical inquiry will remain trapped in recursion. The collapse of modern thought is not an intellectual accident—it is the inevitable result of inherited suppression. But what has been suppressed can be restored. And what has been layered over can be uncovered—if the soul is willing to ascend again.