This appendix applies terminology and diagnostic tools already developed in the main framework—particularly from the Ontology, Semiotics, and Pragmatics sections. Terms such as ontotype, semiotic-token, effigiation, and typophoric projection (e.g., retaining the term Remnant while replacing its referent) are used as defined there and indexed in the Glossary.

At the heart of this diagnostic is a consistent pattern observed throughout salvation history and institutional drift: the visible language of faith (tokens) may persist, even while its anchoring ontological referents are displaced or replaced. When this occurs—when form outlives substance, or when divine markers are retained but redirected toward new meanings—we term it ontosemiotic drift. This phenomenon can result in effigiation: a structure that outwardly gestures toward divine truth while inwardly disconnected from it.

The purpose of this appendix is not to judge sincerity, but to expose this drift where it exists—particularly within the institutional history of Adventism. Section IV explores this mechanism in concrete terms; subsequent sections trace its effect across ecclesiology, authority, and identity.

This case study evaluates the present-day Seventh-day Adventist Church as an instance of institutional drift. We argue that the original referents—such as the confession of the begotten Son, the rejection of creeds, and the prophetic decentralization of the early movement—have been progressively decoupled from the preserved tokens of institutional continuity, denominational language, and administrative structure.

This analysis does not question the right of individuals or institutions to develop theological formulations, but instead evaluates how such formulations, when adopted without fidelity to original referents, may constitute a referential substitution. This is not a critique of sincerity, but of semiotic displacement: how continuity of forms can obscure discontinuity of meaning.

Before proceeding, we affirm a distinction already established elsewhere: that there exists a wider Kingdom of God, as distinct from the Church composed of many sincere believers who may not grasp or articulate the ontological distinctions addressed in this work. These include those who, in moral sincerity, worship according to the light they have received, regardless of denominational affiliation or theological vocabulary.

Accordingly, this appendix does not address the eternal standing of individuals within or outside institutional Adventism. It speaks instead to the ontological legitimacy of a structure that claims to be the visible remnant of prophetic fulfilment. The issue of the Christian Unawares is address in the DM section (II.F.).

The critique offered here is directed not at individual members—many of whom may remain spiritually aligned with divine light—but at the institutional semiotic drift by which visible language and structural authority have diverged from original referential grounding.

This case study is therefore an intra-framework diagnosis, not a salvific verdict. It concerns ontological alignment, not personal sincerity. The concern is whether the institutional referents still correspond to the divine ontotype that first instantiated the Pioneer Advent movement.

Finally, doctrinal matters related to the ontological relationship between the Father and the Son—including the categories of substantive ontohomogeneity, distinct ontorelationality, and the emanative status of the Holy Spirit—are addressed comprehensively in Appendix A of this framework. That appendix provides the metaphysical foundation from which this institutional diagnosis proceeds and need not be reduplicated here.

The institutional claim of the present-day Seventh-day Adventist Church is straightforward: that it is the direct and uninterrupted continuation of the divinely initiated Advent movement, and therefore any group or individual operating outside its administrative structure is by definition illegitimate or schismatic. This claim is often summarized in the assertion, “The pioneers never envisioned another remnant or movement.”

This framing relies on a structural view of continuity—suggesting that institutional visibility and succession equate to divine endorsement. But this assumption fails under closer ontological and semiotic analysis. It confuses token preservation with referent fidelity.

This analysis takes seriously the claim that the present-day Church is the continuation of the original movement. But what exactly constituted that original movement? Throughout this appendix, the term pioneer Adventism refers not merely to an early phase of denominational history, but to a distinct ontological instantiation of the Advent movement—a people called into being by divine confrontation with truth between 1844 and approximately 1890.

This period was marked by:

Ellen White repeatedly affirmed that God had “called out” this movement and entrusted it with a specific light and prophetic burden. She wrote: “God is leading out a people... He is purifying unto Himself a peculiar people, zealous of good works. This is the great day of His preparation.” — Testimonies for the Church, Vol. 1, p. 190.

Elsewhere she identified the first fifty years of the Advent movement as the period in which its core pillars were laid, warning: “The truths that we received in 1844, the truths that we have been proclaiming for the last fifty years, are as certain as eternal truth.” — Special Testimonies, Series B, No. 7, p. 57 (1905)

Thus, pioneer Adventism refers to more than historical origins—it refers to the specific referential framework God originally instantiated. The goal of this appendix is not to venerate a past era, but to evaluate whether current institutional Adventism retains those original referents, or whether it has replaced them with structural tokens divorced from divine instantiation.

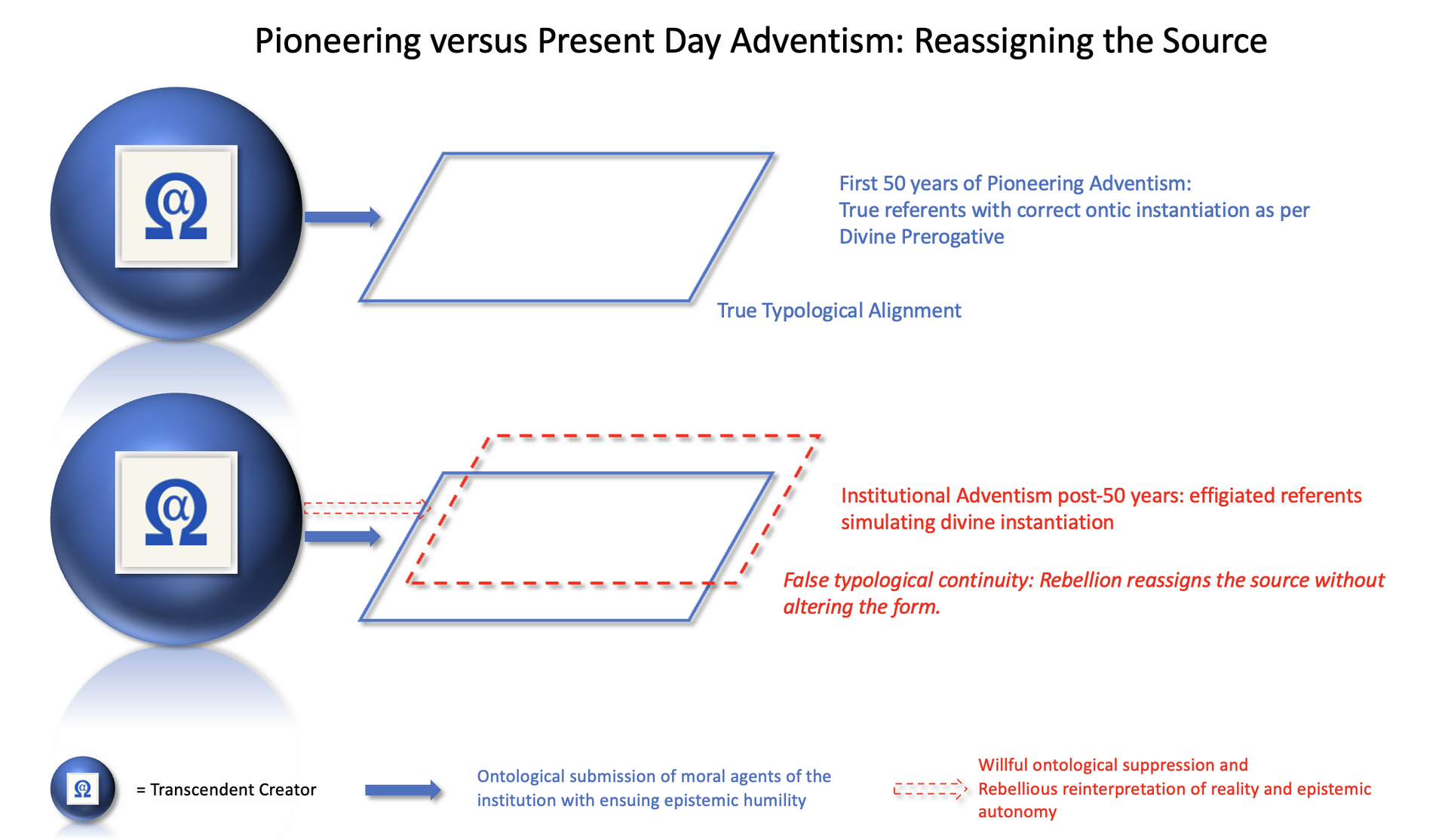

Typological Continuity vs. Reassigned Source: Visualizing Effigiation in Institutional Drift

The diagram illustrates the visual and semiotic similarity between true typological alignment and its effigiated counterpart. Though forms persist, the ontological source is reassigned—resulting in pseudo-instantiation masquerading as legitimate continuity.

Within the framework of this analysis, the question is not: Has the Church maintained its institutional form? The real question is: Has it preserved its original ontological confession?

This shift in focus reveals a critical disjunction: the Adventist pioneers grounded their identity not in organizational succession, but in active confession of revealed truth, particularly the begotten Sonship of Christ, the rejection of human creeds, and submission to ongoing prophetic correction.

As Jesus declared:

“Upon this rock I will build my Church.” (Matt. 16:18) —referring not to Peter, nor to ecclesial structure, but to Peter’s confession of the divine Sonship of Christ.

This confession, not succession, is the ontological foundation of the Church. The moment the confession is altered or displaced—even if the institutional name and language remain—there is a referential discontinuity. What persists may look like the Church, sound like the Church, and function like the Church—but it no longer is the Church in the ontological sense described in Scripture.

This is the tension we aim to trace.

This appendix applies a conceptual distinction already developed in the Ontology and Semiotics sections of this framework. The terms employed here—onto-type, semiotic-token, typophora, effigiation, and pseudo-instantiation—are not new. They have been previously defined, explained, and illustrated, and are also available in the project’s Glossary for quick reference. The purpose of this section is not to reintroduce them, but to apply them directly to the historical and theological case of Adventist institutional identity.

At the heart of this analysis lies the principle of ontosemiotic integrity: that a community, doctrine, or structure must retain not only its outward signs (semiotic-tokens), but also remain anchored to the divine referent or onto-type to which those signs originally pointed. Ontosemiotic drift occurs when visible tokens remain in use, but their alignment with the original ontological referent is lost—whether gradually, unconsciously, or by institutional recoding. The result is effigiation: symbolic continuity covering over ontological discontinuity.

As laid out in the Ontology section (§III) and elaborated in the Semiotics section (§V), the distinction is as follows:

The onto-type refers to the divinely defined ontological kind—what God determines a thing to be by His own prerogative. In the case of the Church, this refers to the called-out body of believers defined by a specific ontological confession: Thou art the Christ, the Son of the living God (Matt. 16:16–18). This confession is not merely propositional—it establishes the Church’s ontological foundation.

The semiotic-token refers to the visible, linguistic, or structural signifier that gestures toward the type—terms like Church, Remnant, Spirit of Prophecy, or denominational identifiers such as Seventh-day Adventist. These tokens are valid only insofar as they remain faithfully anchored to the referent.

The core diagnostic question of this appendix is therefore not whether the SDA institution continues to use biblical language, but whether it continues to inhabit the referent. In other words: does it still instantiate the Church as defined ontologically by God, or does it now merely project institutional continuity through repopulated tokens that no longer carry their original load-bearing referents?

Finally, it must be stated—as also affirmed in the earlier section on theodicy—that this analysis does not apply to the wider Kingdom of God, nor to sincere Christians outside denominational identity. Many walk in reverence before God without access to—or even knowledge of—Adventism's historical claims. Our concern here is strictly with those who claim continuity with the original Adventist movement, and who assert that their institutional form is ontologically identical with the movement God once confronted into being. This is the claim we now place under referential and ontological examination.

The early Adventist movement was not merely a sociological response to historical conditions, nor a theological offshoot of existing Protestantism. It was, in the strictest sense, a divine instantiation: a moment in which God confronted history with truth, called forth a people, and established a new ontological category of witness in anticipation of final judgment. It was a movement rooted not in innovation, but in alignment—a realignment to divine law, sanctuary typology, and the cosmic judgment underway. This movement, as it emerged from the 1844 disappointment, was not invented; it was confronted into being.

The Church, in this founding form, was not defined structurally but confessionally and covenantally. It was those who responded to the revelation of Christ as ontological High Priest, who accepted the authority of the heavenly sanctuary, and who bore public witness to the investigative judgment as a moral and eschatological reality. In other words, it was not merely a set of doctrines that gave birth to Adventism—it was the confrontation of persons with divine referents, resulting in relational fidelity. This constitutes a true onto-type: a divinely specified kind with boundaries defined not by institutions but by moral, relational, and covenantal criteria.

The core themes of the 1872 and 1889 Fundamental Principles reflect this ontotype. These documents, unlike later creedal statements, were not designed to be exhaustive, juridical, or controlling. They explicitly disavowed the role of creed and offered instead a descriptive summary of shared convictions. Among these were:

Belief in God the Father as Creator and sovereign source of all life;

Confession of Jesus Christ as the begotten Son of the Eternal Father, and through whom all things were made;

The reality of the heavenly sanctuary and the ongoing investigative judgment initiated in 1844;

The continuing moral authority of the Ten Commandments, including the seventh-day Sabbath as the mark of divine rest and eschatological sign;

The second coming of Christ as imminent and literal;

The conditional immortality of the soul, rejecting eternal torment;

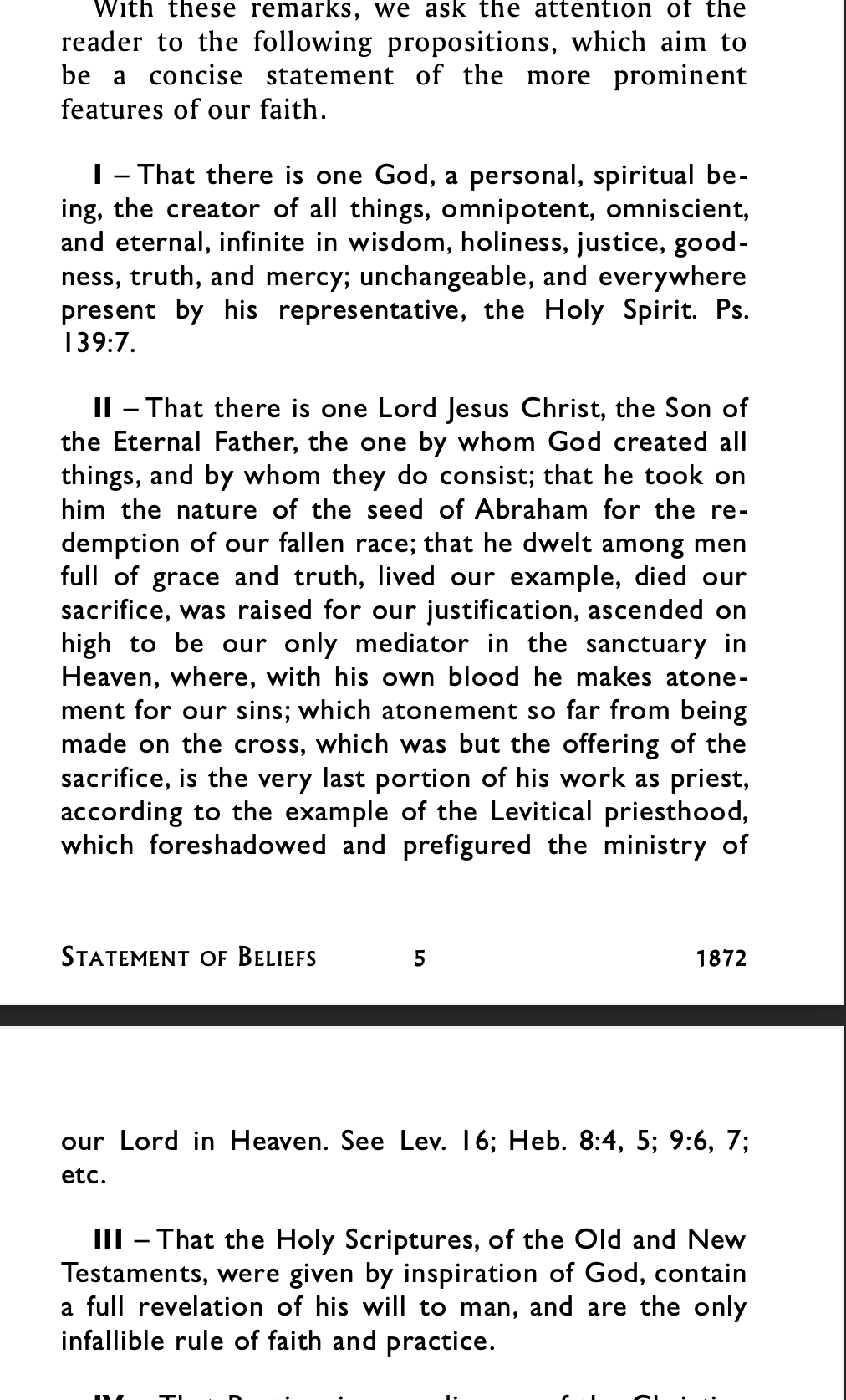

Statement of Beliefs (1872), Articles I–III. God is defined as “one God, a personal, spiritual being… present by his representative, the Holy Spirit.” Christ is presented as “the Son of the Eternal Father,” the one through whom all things were created. No language of co-equality or co-eternality is used, nor is the Holy Spirit identified as a third person. These foundational propositions reflect ontological restraint and referential clarity, in contrast to later metaphysical formulations.

Crucially, these principles made no reference to the Trinity, to a metaphysical personhood of the Holy Spirit, or to any forensic theory of atonement. Their silence was not an oversight, but a reflection of theological restraint—a deliberate refusal to define what had not been decisively revealed. Their Christology was non-Nicene, rooted in biblical revelation, not conciliar formulation. The Spirit was treated not as a third “person” in a co-equal metaphysical sense, but as the presence and power of God—emanative, active, and relational, not abstract or ontologically partitioned. The full 1872 document can be downloaded here as a pdf file.

In this way, pioneering Adventism reflected referential clarity and ontological humility. Its tokens pointed to a shared type: a movement initiated by divine confrontation, upheld by moral alignment, and marked by eschatological urgency. It had not yet been effigiated, creedalized, or structurally reified. It could be disrupted—but it could not yet be replaced. And that is precisely why, as we shall see, later developments represent not mere growth, but ontosemiotic drift.

If the early Adventist movement was an ontologically grounded instantiation—a covenantal body aligned with divine referents—then any claim to institutional continuity must be evaluated not by succession alone but by whether those referents have remained intact. The concept of ontosemiotic drift becomes operative when the tokens (language, symbols, doctrines) persist, while the referents they once signified begin to shift. This section identifies the mechanisms by which that drift has occurred.

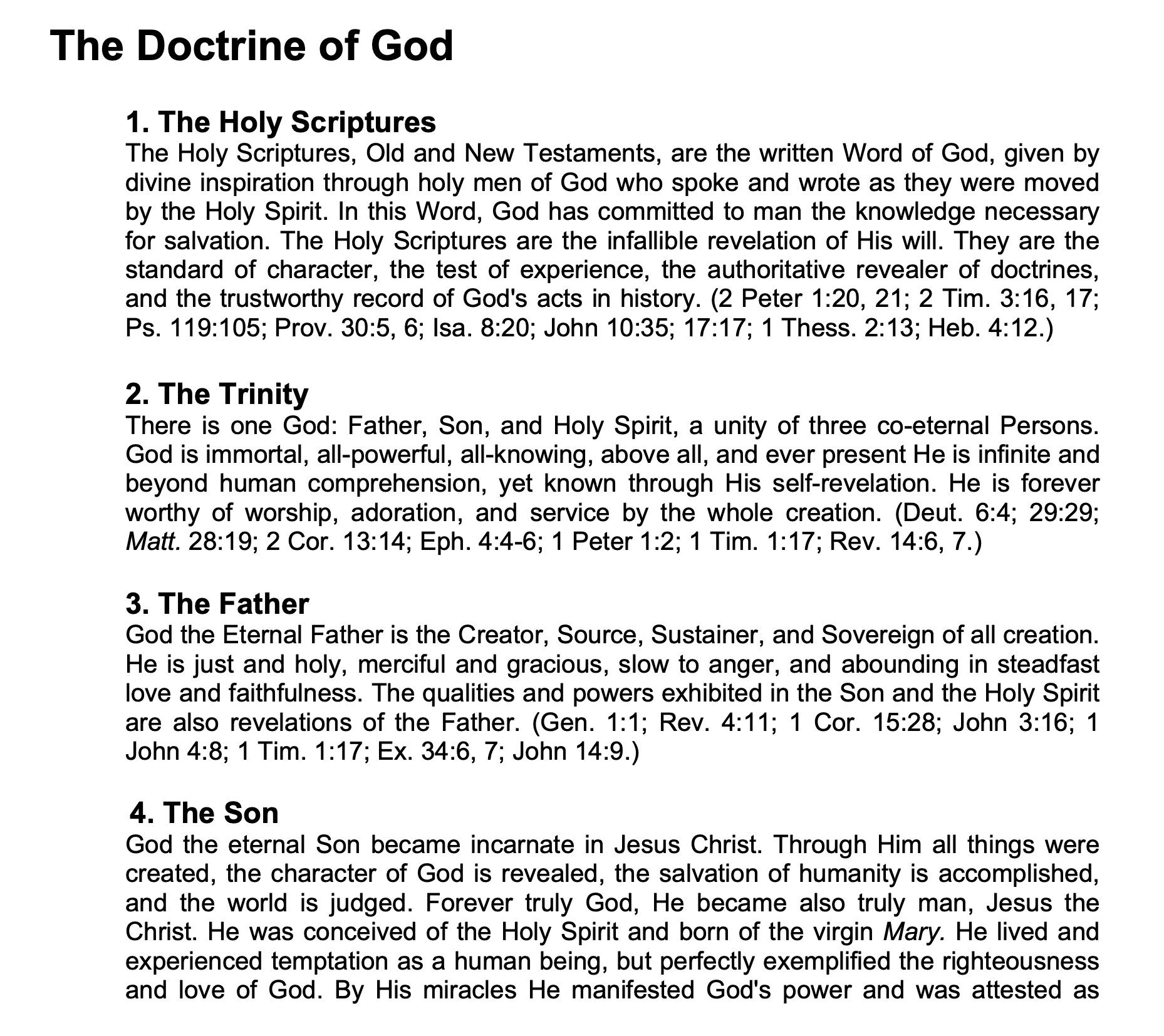

The earliest summaries of Adventist belief (1872, 1889, and 1894) were explicitly non-creedal and presented as provisional, descriptive outlines. In contrast, the 1980 “Fundamental Beliefs” introduced a prescriptive framework—fixed, numerically ordered, and implicitly creedal. What had once been a witness to living truth became a boundary mechanism, defining institutional orthodoxy rather than referential alignment. The 1980 document can be downloaded here as a PDF file. The first four reformulations of the fundamentals are shown below, and should be compared with the original above.

Creeds are not wrong in themselves, but they become semiotic substitutes when they function as signs of belonging rather than confrontations with truth. In this shift, the emphasis moved from “we confess what God has revealed” to “we assent to what the Church has defined.” This reflects a typological inversion: fidelity is no longer measured by relationship to the referent, but by verbal agreement with institutional summary.

Between 1913 and the late 20th century, the SDA Church gradually absorbed external theological categories—particularly from Nicene Trinitarianism and Protestant systematic theology. Terms like “co-eternal,” “three persons,” and “vicarious substitution” entered official discourse without ever having been part of the original Adventist ontotype.

These are not neutral updates. They represent an importation of metaphysical structures foreign to the early movement's biblical realism. The Church's once-restrained formulations gave way to abstract personhood definitions and legal-atonement language that subtly reframed the meaning of Christ, the Spirit, and the plan of salvation. This was not development—it was referential substitution, under familiar tokens.

Originally, Adventism operated on a decentralized, movement-based model in which prophetic confrontation (especially through Ellen White) functioned as a moral counterweight to institutional control. But from the 1901 General Conference reorganization[1] onward, administrative structures increasingly absorbed interpretive authority.

In time, the General Conference in Session came to be viewed as the highest ecclesiastical authority on earth, with its decisions described—even recently—as the “voice of God.”[2] This consolidation of authority represents not just organizational efficiency, but a semiotic shift: from divine confrontation to institutional proclamation. Interpretive infallibility was never claimed doctrinally, but it began to operate functionally—especially when dissent or reform was labeled as disunity or rebellion.

The early Adventist movement spoke in the unmistakable language of moral confrontation—Babylon, judgment, apostasy, prophetic separation. These were not simply rhetorical flourishes; they were ontological signals of identity. To be Adventist was to be called out, morally distinct, and under judgment.

In contrast, contemporary denominational rhetoric has largely repositioned Adventism as a global, inclusive, service-oriented faith tradition—emphasizing growth, presence, and humanitarian impact. While these are not inherently wrong, they operate as narrative replacements, softening or marginalizing the original prophetic urgency. The voice of confrontation has been replaced by the language of diplomacy and respectability.

Language within the institutional Church has preserved many of its historical tokens—“Spirit of Prophecy,” “Remnant,” “Three Angels’ Messages.” But these tokens often no longer signify what they once did.

The term Spirit of Prophecy now more commonly refers to Ellen White’s published corpus, historically honored but rarely treated as a continuing prophetic voice for moral confrontation. This framing is visible in institutional emphasis on her writings as a denominational legacy rather than an active gift of warning, correction, or rebuke (see Fundamental Belief 18 and Adventist.org/Spirit-of-Prophecy).[3]

The term Remnant has likewise shifted. While originally defined by relational separation, judgment fidelity, and prophetic confession (Rev. 12:17; 14:6–12), it is now often institutionalized—referring to global cohesion, doctrinal uniformity, and organizational visibility (see SDA Church Manual, 2022 ed.). The structure remains, but the moral and covenantal distinctives have been displaced.[4]

This is the crux of typophoric substitution: the term is retained, the referent is replaced. What once denoted an ontological category (divinely initiated identity) now functions as a brand carrier or organizational token. Such drift does not merely soften language—it reframes identity.

These examples are not isolated; they illustrate the broader semiotic erosion discussed in previous sections. In what follows, we trace how this token-referent inversion has played out in institutional claims to authority and continuity.

A clear contrast can be seen in modern Adventist language. For example, the official SDA Church website describes its mission as: “To make disciples of Jesus Christ who live as His loving witnesses and proclaim to all people the everlasting gospel of the Three Angels’ Messages in preparation for His soon return.” Yet in other settings, this has been generalized to: “Our mission is to share hope and wholeness around the world.”[5]

This shift in language reflects a semiotic dilution: the original token (Three Angels’ Messages) is retained, but its referent—eschatological confrontation and judgment—is softened into therapeutic language.

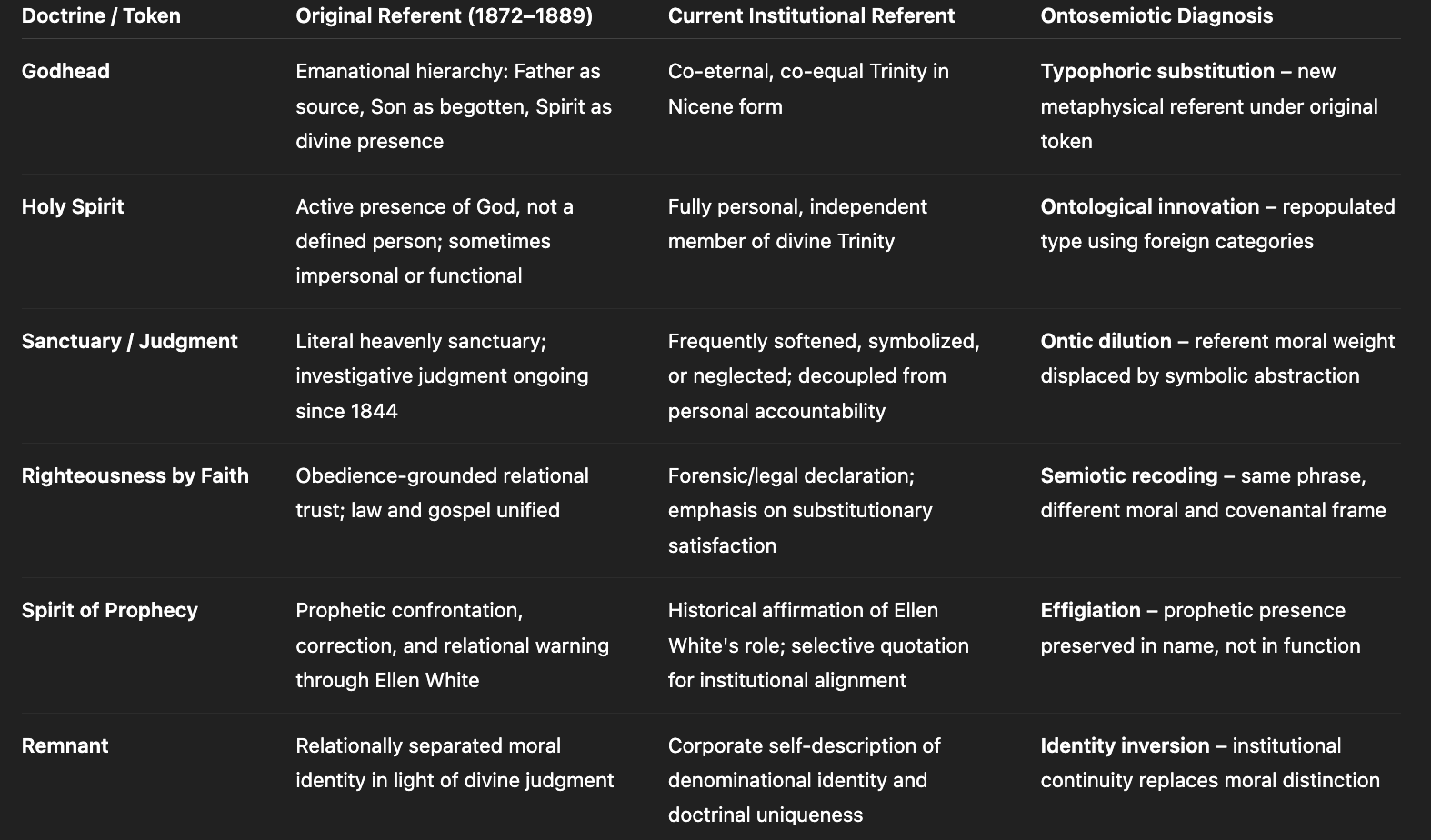

To make the ontosemiotic drift tangible, we now examine how key theological terms—still in active use within the institutional SDA Church—have undergone typophoric substitution. These terms (or tokens) persist linguistically, but no longer consistently refer to the same ontological realities they once signified. The token remains, but the referent shifts. This phenomenon is what the framework has earlier defined as pseudo-instantiation: when an outward form mimics fidelity while internally repopulating its content.

We now present a side-by-side typophoric analysis of six key Adventist terms, comparing their historical referents (as reflected in the 1872/1889 Fundamentals and early praxis) with their functional meaning in contemporary denominational usage.

This comparative grid reveals a common pattern: verbal retention + referential drift. The Church has kept the tokens in circulation but reassigned their underlying referents, sometimes imperceptibly and other times overtly. This allows for the illusion of continuity without ontological alignment. See Footnote on Godhead.[6] Fundamentals can be downloaded here: 1872 & 1980 .

In practical terms, this means the Church can still say:

“We believe in the Three Angels’ Messages,” while proclaiming them in softened, metaphorical, or symbolic terms.

“We believe in the Spirit of Prophecy,” while neutralizing or selectively domesticating its confrontive power.

“We are the Remnant,” while abandoning the theological conditions that once defined remnancy—moral separation, apocalyptic urgency, and divine confrontation.

This is not to accuse all members or leaders of conscious deception. Many may sincerely believe they are maintaining the legacy of the pioneers. But the point of ontosemiotic analysis is that drift does not require bad faith—only a misalignment of referent beneath a persistent token. Once that dislocation occurs, even the most sincere loyalty to language can become semiotic error.

The integrity of the original onto-type—pioneering Adventism as a divine instantiation—is not preserved by verbal continuity, but by referential fidelity. When that fidelity is lost, the tokens become typophoric projections, functioning as theological placeholders with no ontological anchor. And when these projections are mistaken for presence, the Church ceases to be a witness and becomes instead a simulation.

Transition Note: Having addressed the nature of institutional self-authorization, we now examine the clearest instance of referential drift within Adventism: the shift from the pioneers’ confession of the begotten Son to the later adoption of the Trinity doctrine. This is not a polemic against Trinitarian belief, but a case study in typophoric substitution.

Any theological analysis of institutional drift must address the Trinitarian shift that occurred within Adventism in the 20th century. This shift represents one of the clearest examples of referential substitution under a preserved token, and thus qualifies—within this framework—as a significant moment of ontosemiotic drift.

It is important to state at the outset that this analysis does not deny the sincerity or legitimacy of Christians who, in good faith, hold to a doctrine of the Trinity. Nor do we deny the freedom of theological communities to formulate their understanding of God in ways they believe best reflect scriptural witness. This section is not an ontological critique of the Trinity per se, but a diagnostic evaluation of how the doctrine's later adoption within Adventism functions as a departure from its original referent base—and therefore represents an ontological displacement, even if the token (e.g., Godhead [6]) remains.

A defining feature of early Adventism was its rejection of creeds—not merely as a matter of denominational preference, but as a foundational epistemological and ecclesiological posture. The pioneers believed that static human formulations tended to replace divine initiative with institutional control. Truth, in their view, was to be relationally revealed and progressively understood, not codified in abstract propositions.

“The Bible is our creed. We reject everything in the form of a human creed. No creed but the Bible is our motto.”

— James White, Review and Herald, June 4, 1861

“The first step of apostasy is to get up a creed, telling us what we shall believe. The second is to make that creed a test of fellowship. The third is to try members by that creed. The fourth to denounce as heretics those who do not believe that creed. And fifth, to commence persecution against such.” — J.N. Loughborough, Review and Herald, October 8, 1861

This principled resistance to creeds was not limited to church governance—it extended to how early Adventists approached the doctrine of God. The pioneers deliberately refrained from importing extra-biblical formulations like the Trinity, not out of ignorance, but from a conviction that creeds tend to ossify partial truths and suppress ongoing light.

These warnings were not rhetorical flourishes but reflected a deep suspicion that creeds would institutionalize partial light, inhibit prophetic correction, and transform a Spirit-led movement into a typological simulation—where the semiotic shell remains while the ontological referent is lost.

This foundational suspicion of creeds shaped the content and tone of early Adventist belief. The 1872 and 1889 Fundamental Principles—as well as the theological writings of pioneers like James White, J.N. Andrews, and Joseph Bates—make no reference to the Trinity. Christ is presented as the begotten Son of the Father, pre-existent and divine, but not co-eternal or co-equal in the Nicene metaphysical sense. The Holy Spirit is described as the presence and power of God, not as a third, ontologically distinct person.

This absence was not due to confusion or lack of theological development. It was a deliberate restraint, born from the conviction that Scripture should speak in its own categories, not be retrofitted with Greek philosophical metaphysics. Ellen White herself never used the term “Trinity” and did not frame the “Godhead”[6] in terms of tripersonalism. Even her later references to the Holy Spirit as a “person” must be read in the context of function, mission, and presence, not as affirmations of ontological parity within a co-equal triad.

Thus, early Adventism did not just differ in doctrine—it differed in epistemology. Its refusal to adopt creeds was a refusal to cede control of meaning to semiotic institutions. And its early formulations reflect an alignment not with Nicene categories, but with biblically revealed ontotypes, relationally disclosed and reverently confessed.

The Church’s formal movement toward Trinitarianism culminated with the 1980 Fundamental Beliefs , where the doctrine of the Trinity was articulated in classically Nicene terms: one God in three co-eternal persons. This formulation marked a decisive shift in ontological referent—from a biblically grounded, relationally hierarchical Godhead to a philosophically abstract, co-equal metaphysic.

While the term Godhead was retained, its referent was changed. No longer did it signify the Father as the ontological source, the Son as begotten, and the Spirit as divine agency. Instead, it now referred to a shared essence among three indistinguishable hypostases, grounded in the language of post-biblical councils. This is the definition of typophoric substitution: when a familiar theological token is preserved but its ontological referent is silently replaced.

The biblical term Godhead (used only three times in the KJV [6]) never denoted numerical composition or tri-personal structure. It referred instead to divinity as essence (theotēs), divine nature (theiotēs), or the divine itself (theion). The retroactive application of Trinitarian categories to these texts is a product of post-Nicene theological scaffolding, not of original scriptural usage.

(This framework-analysis affirms the full divinity of Christ; the concern is not subordinationism, but ontological ordering—specifically, whether the adopted categories correspond to biblical instantiation or post-biblical abstraction. See Appendix A for a full ontological analysis.)

The early Church used non-Trinitarian categories and intentionally withheld speculative formulations.

The later Church adopted Trinitarian metaphysics, drawn from external philosophical systems, and embedded them in its doctrinal core.

This change occurred without discarding the original tokens (e.g., Godhead, Spirit, One Lord), which created the illusion of continuity.

Therefore, the Trinitarian shift in Adventism represents not merely doctrinal clarification, but a referential repopulation of language—one that no longer instantiates the original onto-type.

Transition Note: With the theological shift now outlined, we turn to its structural implications—how language, authority, and identity within the institutional Church have evolved. This section examines how visible tokens may remain while divine referents are displaced, and how authority may be preserved in form while losing its ontological grounding.

Institutions that once bore authentic witness to divine truth do not retain legitimacy by inertia. The authority of the early Seventh-day Adventist Church arose not from formal structure, global recognition, or bureaucratic continuity, but from its identity as an instantiated ontotype—a people called out by God to bear witness to a specific eschatological truth. When the referents that originally defined that calling are replaced or redefined, structural continuity becomes referentially hollow. The institution may echo the former voice, but it no longer speaks with instantiatory authority.

A common institutional defense is that the pioneers “never envisioned another movement,” and therefore all dissenting groups must be illegitimate by default. This argument assumes that denominational continuity is synonymous with theological and ontological faithfulness—a claim that collapses under scrutiny.

What the pioneers actually insisted upon was not loyalty to structure, but fidelity to revealed truth. The identity of the early Advent movement was grounded in moral separation, eschatological proclamation, and ontological clarity regarding the Godhead, the sanctuary, and the Sonship of Christ. Once those referents are displaced, the structure may endure, but its claim to legitimacy no longer rests on divine instantiation.

Some may respond that “present truth” allows for theological development beyond what the pioneers held. And indeed, present truth is a biblical category (2 Pet. 1:12)—but one that never contradicts prior divine revelation. True present truth does not replace what God once revealed; it fulfills and clarifies it. As Isaiah wrote, “To the law and to the testimony: if they speak not according to this word, it is because there is no light in them” (Isa. 8:20). Even Christ affirmed that He came not to destroy the law or the prophets, but “to fulfill” them (Matt. 5:17). Any development that redefines foundational referents—such as the identity of the Son, the sanctuary, or the remnant—is not progression but departure. Present truth deepens fidelity; it never reassigns divine intent.

This produces what the present framework identifies as semiotic simulation: the tokens remain, but their referents have drifted. The Church still employs familiar language—Remnant, Spirit of Prophecy, Judgment, Second Coming—but these no longer point consistently to the realities once revealed. The result is theological continuity in sound, but not in substance.

A Church that proclaims sacred vocabulary but no longer points to the same ontological types is no longer the same Church in the biblical sense. It may be descended historically, but ontologically, it has become a successor entity—preserving the form while abandoning the ground of its original calling.

This invites a central ecclesiological question: What defines the Church? According to Scripture, it is not a formal institution, but a body of confessors—those who acknowledge the ontological Sonship of Christ as revealed in Peter’s confession (Matthew 16:16). Christ responded not to Peter’s status, but to that confession: “Upon this rock I will build my Church.”

It is that confession, not administrative succession, that delineates the true body of Christ. Those who return to the original referents of Adventism—regardless of organizational affiliation—may therefore be closer to the ontological Church than the institutional body that claims its name.

This is not a charge of rebellion, but a framework-based analysis of referential continuity. The critical question is not who left the structure, but who remains aligned with the original referential confession.

Those who insist that the pioneers “never envisioned another remnant” assume that structural visibility defines legitimacy. But as shown in Section IV, this is a textbook case of typophoric substitution: the tokens remain (Church, Remnant, Spirit of Prophecy), but their referents have been redefined or abandoned. The Church has become a token of succession, not necessarily a bearer of divine instantiation.

The pioneers confessed the begotten Son (a fixed scriptural referent), rejected creeds, embraced moral separation, and submitted to divine judgment. Modern Adventism has in many cases shifted those referents—sometimes subtly, sometimes openly—without reexamining its ontological foundations.

Those who now return to those referents are not innovators, but returnees. In preserving form while losing referent, the institution becomes the one who has departed.

The modern Church often invokes Ellen White’s 1889 statement that “the judgment of the General Conference… is the highest authority that God has upon the earth,” claiming decisions made in Session represent the “voice of God” (3T 492). This language is now embedded in denominational policy and used to consolidate authority.

Yet White herself reversed that statement just over a decade later: “It has been some years since I have considered the General Conference as the voice of God.” — Manuscript 37, 1901. This was not merely a retraction—it was a theological correction. She recognized that moral authority had been replaced by institutional reflexivity. The referent—God’s initiating voice—was no longer reliably present, even as the token remained.

The current General Conference Working Policy (B 95 05, 2022–2023) still affirms:

“The General Conference in Session, and the General Conference Executive Committee between Sessions, is the highest ecclesiastical authority in the Seventh-day Adventist Church under God. Its decisions are to be respected by all levels of church organization.”

This is a clear case of typophoric projection—where a divine token (the “voice of God”) is retained, but ontologically severed from its source. Bureaucratic pronouncement masquerades as divine communication. The result is not revelation, but simulation: an institutional echo deployed to suppress critique and insulate authority from prophetic correction.

This pattern is not unique to Adventism. Whenever the people of God traded presence for structure, God raised prophetic voices to restore referential alignment. From Elijah at Carmel to John in the wilderness, revival always followed referential realignment.

This trajectory calls not for protest, but for prophetic confrontation—a realignment of tokens with their divinely appointed referents.

Throughout salvation history, sacred forms often persisted while alignment with divine reality was lost. In each case, God raised prophets to call His people back to already-revealed realities. Prophets were not innovators, but referent restorers. Ellen White’s ministry followed this path: she did not elevate new tokens, but safeguarded the meaning of those entrusted to the early movement.

Today, the same call applies. True reformation is not about novelty or structure—it is about restoring the referents behind the forms. Cosmetic change without ontological recalibration only perpetuates the drift in new language. Restoration is not rebellion—it is reinstantiation.

Prophets reestablish referent clarity, not invent new systems.

The institutional Church today needs prophetic confrontation, not cosmetic reform.

Recovery of the Adventist witness depends on restoring ontological and semiotic fidelity—not just doctrine, but meaning.

The role of reformers today is not rebellion, but re-instantiation—a return to God’s original referential call.

We now invite the reader—not merely as observer, but as moral participant—to consider whether the current Adventist identity, as affirmed is structurally inherited or ontologically aligned to that of the Pioneers. The distinction is not academic; it is spiritual. Fidelity, in biblical terms, is never defined by possession of tokens, but by relational participation in divine referents. Let each consider, therefore, whether the forms they uphold still point to what God originally instantiated.

To return to the original referents of Adventism, as defined by the Pioneers (foundational pillars established in the first 50 years) is not an act of schism—it is an act of fidelity. It is not rebellion against authority but a response to a higher authority: the authority of God’s ontological disclosure and the prophetic witness that first instantiated the Advent movement. Those who recover the original foundations are not innovators—they are realigning with what God originally initiated.

Rebellion occurs when one separates from God's order to follow a self-willed path. But when an institution itself has veered from the ontological and covenantal foundations upon which it was built, continuing in structural alignment may become a form of complicity. In such cases, what may superficially appear as dissent actually seeks referential realignment, this is not rebellion, but restoration. It is not the beginning of a new movement, but the continuation of the original one—from which the visible structure has drifted.

The accusation that those who seek to recover original referents are “causing division” fails to ask: division from what? If the divergence is from the biblical referent, then conformity is no virtue. The true Church is not defined by institutional name, but by referential alignment with divine reality—revealed in the confession of the Son, in covenantal obedience, and moral fidelity to God’s call.

As previously examined in VII.E, the institutional Church has preserved many sacred terms—Godhead, Remnant, Spirit of Prophecy, Sanctuary, Present Truth—but in many cases, these tokens have become detached from their original referents. What remains is a semiotic shell: language retained for continuity, but emptied of the ontological realities it once signified.

The call today is not to discard these tokens, nor to preserve them uncritically—but to re-anchor them. This requires deliberate repentance, theological reformation, and ontological realignment. Every Adventist expression—whether spoken, sung, taught, or published—must be measured not by historical familiarity, but by its fidelity to the divine realities originally revealed.

This is not a cosmetic task. It is a moral one. The recovery of meaning begins not with slogans, but with submission to the referent. Only then can the tokens of Adventism function again as vessels of divine truth, rather than signs estranged from sanctified source.

This appendix has traced the onto-semiotic drift that has occurred between the pioneering Adventist Church and the current institutional body that bears its name. Drawing upon the framework's earlier definitions of ontotypes (divinely determined realities) and semiotic tokens (linguistic or ritual expressions that signify those realities), we have shown that:

The original Adventist movement was an instantiation of divine purpose—ontologically grounded in the confession of the begotten Son, the sanctuary judgment, covenantal accountability, and prophetic separation.

Over time, the institutional SDA Church has retained the tokens (language, forms, claims) while drifting from the referents—substituting or softening foundational truths through creedal adjustment, philosophical redefinition (e.g., Trinity doctrine), and structural self-justification.

Institutional continuity is not ontological continuity. Form without referent becomes effigiation—the simulation of divine presence without divine authority.

In Scripture, the true Church is defined not by succession or global visibility, but by ontological confession—“Thou art the Christ, the Son of the living God” (Matt. 16:16).

Therefore, those returning to the original confession and referents are not rebels but restorers—participants in the re-instantiation of the original body.

Conversely, the modern institution—though structurally intact—may no longer qualify as a valid instantiation if its referents have shifted.

Prophetic reform must begin not with bureaucratic appeals but with semiotic and ontological reorientation—recovering what God once revealed and confronting what has been obscured.

⚠️ The remnant is not where the label remains, but where the referent lives.

⚠️ The true Church is not defined by what it calls itself, but by what it confesses and embodies.

This case study demonstrates that onto-semiotic analysis is not merely a philosophical tool—it is a necessary instrument of theological discernment in an age of institutional simulation. To return is not to rebel; it is to obey the Voice that first called the Church into being.

While truth may unfold across time, that unfolding must remain anchored to what God has already revealed. Present truth does not negate past referents; it clarifies and builds upon them. As Peter affirmed, we are to be “established in the present truth” (2 Pet. 1:12), yet that present truth must speak “according to the law and to the testimony” (Isa. 8:20), not against it. Christ Himself declared that He came not to abolish what had been given before, but “to fulfill” it (Matt. 5:17). True reform never departs from divine instantiation, but realigns with it—deepening fidelity rather than displacing foundations.

Footnotes

[1] The 1901 and 1903 General Conference sessions marked a turning point in Adventist governance. Though the 1901 reforms introduced union conferences to encourage decentralization, the 1903 GC constitution shifted interpretive and administrative authority to the General Conference Executive Committee, effectively centralizing governance. Ellen White warned against this trend, referring to it as "kingly power" (TM 361; Letter 81, 1900). For detailed analysis, see George R. Knight, Organizing for Mission and Growth (Review & Herald, 2006), and Barry D. Oliver, Structure and Authority in the Seventh-day Adventist Church (PhD diss., Andrews University). See also evolving GC Working Policy B 05.

[2] The phrase “the voice of God” in reference to General Conference decisions originates from Ellen White’s 1889 statement in Testimonies for the Church, Vol. 3, p. 492, where she cautioned against resisting unified decisions. However, she later reversed this, writing, “It has been some years since I have considered the General Conference as the voice of God” (Ms 37, 1901). Despite this, GC Working Policy B 95 05 (2022–2023) still declares that the GC in Session “is the highest ecclesiastical authority… under God,” and that its decisions are binding across the denomination—effectively reasserting a version of divine authority.

[3] In early Adventism, the Spirit of Prophecy—understood as an active gift of prophecy—was embodied in living prophetic voices like Ellen White, offering ongoing correction and moral guidance. Since her death, however, the term has increasingly referred to her historical writings rather than an active, confrontational prophetic presence. This shift is reflected in official language such as Fundamental Belief 18 (Seventh-day Adventist Church Manual, 19th ed., 2022), which affirms her writings as a continuing and authoritative source of truth, yet institutional usage often restricts the term to archival respect rather than living prophetic function. The phrase Spirit of Prophecy has thus undergone a typophoric shift: the token is preserved, but its referent—ongoing divine confrontation—is diminished or functionally absent.

[4] In contemporary Adventism, the term Remnant is often framed institutionally—as a globally interconnected body unified by doctrinal identity and organizational structure—rather than as a relational, judgment‑anchored moral identity. For instance, the Seventh-day Adventist Church Manual (19th ed., 2022) defines the Remnant in terms of keeping commandments, proclaiming the Three Angels' Messages, and functioning as the “lowest level of ecclesiastical authority” within a global Church—as if the marker of Remnant was institutional cohesion rather than covenantal. Historically, though, the Remnant was understood in deeply moral terms: a small group called out from apostasy, anchored in judgment, and faithful to the prophetic-confessional witness (Rev. 12:17; Rev. 14:6–12). This shift reflects a typophoric displacement—the token (Remnant) remains, while its referent has migrated from relational fidelity under divine judgment to organizational continuity and doctrinal preservation.

[5] A clear contrast emerges in modern Adventist mission language. The official SDA Church website (https://www.adventist.org/world‑church/) defines its mission as: “To make disciples of Jesus Christ who live as His loving witnesses and proclaim to all people the everlasting gospel of the Three Angels’ Messages in preparation for His soon return. ”Yet other denominational platforms, such as the North American Division’s website (https://www.nadadventist.org/hope-and-wholeness), generalize the mission into: “To reach North America and the world with the distinctive, Christ‑centered, Seventh‑day Adventist message of hope and wholeness.” This evolution in wording illustrates a typophoric shift—retaining the mission token (Three Angels’ Messages) while displacing the ontological referent of eschatological urgency and prophetic confrontation with a broader, affective emphasis on social wellbeing and emotional uplift. Links access 6/2025.

[6] The term Godhead appears only three times in the King James Version (Acts 17:29, Romans 1:20, Colossians 2:9), and in each case it denotes divine essence, not a tri-personal structure. The underlying Greek terms—theion, theiotēs, and theotēs—all refer to quality, not number. They describe what makes God divine, not how many divine persons exist.The later association of “Godhead” with a triune framework reflects a retroactive metaphysical adaptation. This shift was especially prominent after the Nicene and post-Nicene councils, where Greek philosophical categories were used to formalize a tri-personal interpretation. These categories were later read back into Scripture, overlaying the original referents.

[7] Simulation of presence = effigiation: the maintenance of sacred form while the original ontological referent is absent. The token persists—linguistically or structurally—but no longer instantiates what God originally defined. See also: typophoric projection, pseudo-instantiation.