This section examines the pragmatic dimension of language—not as a neutral vehicle for meaning, but as the site where ontological integrity is either upheld or subverted. While grammar and semantics structure what is said, pragmatics reveals how language functions in context, how it assumes, implies, gestures, and positions. These functions are never morally inert. In a post-structural age, speech acts no longer simply reflect meaning—they often reengineer it. Through deixis, presupposition, implicature, and typophora, speakers may affirm covenantal truth or simulate it. The ethical question is no longer just what a word means, but what kind of ontological world it is inviting the hearer to inhabit. This section exposes the discursive mechanisms by which typological fraud occurs and offers diagnostic tools for discerning whether speech aligns with divine reality or distorts it through consensus, sentiment, or simulation.

Language is never morally neutral. Every utterance—deliberate or unconscious—reveals a posture toward truth. Pragmatics is therefore not a peripheral linguistic tool; it is the arena where meaning meets reality in real time, where intention, expression, and moral alignment converge.

Modern linguistics typically treats pragmatics as a set of socially conditioned mechanisms—deixis, presupposition, implicature, and other context-sensitive inferences—designed to navigate ambiguity and achieve nuance. Beneath the technique, however, lies a deeper transaction: every speech-act implicitly claims what is real, who may name it, and howthat naming must be understood.

Within a biblical framework, pragmatics is the relational outworking of a metaphysical cascade: Ontology → Epistemology → Semiotics → Pragmatics. As language must accord with truth, and truth with being, so speech must accord with covenantal responsibility. To speak is to bear witness—faithfully or falsely—to the reality God has established.

When speech is detached from ontological truth and moral submission, it no longer reveals meaning—it manufactures it. This is the realm of effigiation: rhetorical projection of presence and legitimacy where none has been authorized. Here pseudo-tokens are minted, typophoric gestures are bent, and discursive simulations of divine categories operate without covenantal grounding.

Scripture frames this moral weight explicitly. Jesus warns: “I tell you that for every idle word men shall speak, they will give account of it in the Day of Judgment” (Mt 12:36). The term ἀργόν (argón) means “unfruitful, careless, unaccountable.” If even idle words incur scrutiny, how much more those crafted through manipulative implicature, hidden presupposition, or performative simulation.

Against this backdrop, secular and post-modern discourse wages what this framework calls presuppositional warfare, deploying four recurrent tactics:

Typophoric distortion – mis-gesturing a sign toward a divine type while denying its fixed referent.

Binary pressure – coercive either-or framing that forces false moral choices.

Narrative layering – stacking selective stories until they overwrite legitimate kinds.

Semiotic overload – flooding discourse with slogans or noise to dull discernment.

Each tactic weaponizes pragmatic structure to simulate moral authority while bypassing ontological submission. Recovering faithful pragmatics, then, is not a mere exercise in conversational polish; it is an act of covenantal repentance in speech—restoring every word to correspondence with the One who names reality.

While syntax orders the sentence and semiotics encodes the sign, pragmatics governs how meaning is actualized in context. It attends to the relational dynamics between speaker and hearer, the assumptions that undergird speech, and the inferences that carry a message beyond its literal content. Pragmatics promises nuance and cultural sensitivity—but when context becomes untethered from ontological truth, pragmatics ceases to illuminate meaning and becomes a system for simulating it.

In such a discursive landscape, both speaker and hearer share the burden of discernment. The interpretive act is never neutral. Every utterance embeds a moral claim, and every act of interpretation either receives that claim or absorbs a counterfeit. In a fallen world, the dialogic field itself is corrupted—susceptible to projection, resistance, and manipulation from both sides. This is precisely why pragmatic distortion must be analyzed not merely linguistically, but ontologically and ethically.

This section examines the core components of pragmatics and shows how each can be co-opted to sustain counterfeit typologies, reinforce discursive fraud, and destabilize moral reference.

In pragmatic terms, the weight of manipulation does not rest solely on the speaker. The interpretive burden-and the moral risk—is shared by the recipient, whose noetic posture determines whether a message is discerned, distorted, or resisted. In a fallen world, both speaker and hearer operate under conditions of moral opacity. This analysis does not presuppose a regenerated agent confronting a neutral audience; it presumes a corrupted dialogic field in which resistance, susceptibility, and projection can co-arise in both parties. This mutual fallenness is precisely what makes the need for epistemic and ontological realignment urgent-and why pragmatic distortion is both pervasive and diagnosable.

The pragmatic tools to be examined here—deixis, typophora, implicature, presupposition, context-shift, and allied devices—are not ontological kinds in themselves. Their moral weight comes from how they align or misalign with the ontologically legitimate types already defined by the seven-fold criteria set out in the Semiotics section. Pragmatics therefore functions as an applied extension of semiotic scrutiny at the level of communicative force: it shows how tokens are deployed, not what kinds they are. Consequently, this section is not itself refracted through the seven ontotype criteria; instead, it assumes that diagnostic grid and demonstrates how speech-acts can either uphold or bypass it in real-time discourse.

Deixis is often introduced in terms of person, place, and time—expressions like “I,” “here,” or “now”—but this description refers only to the categories where deixis commonly appears, not its defining feature. The essential property of deictic expressions is that they lack fixed referents; their meaning is determined entirely by the context of utterance—who is speaking, when, and where. Unlike lexical nouns or abstract categories whose referents remain relatively stable across discourse, deictic terms are inherently context-sensitive: “you” means whomever is being addressed; “now” means the moment of speech; “this” may point to a nearby object, event, or even moral proposition, but only within a shared frame of reference. This referential fluidity allows deixis to function as a powerful rhetorical tool: by simulating immediacy, urgency, or communal alignment, it can gesture toward moral or ontological solidarity without ever making the referent explicit. When deictic framing is fused with typophoric reference—e.g., “this justice,” “our truth,” or “now is the time”—it creates a morally loaded impression of shared conviction while concealing a potentially fabricated or shifting referent. This is not classical deixis, but a form of rhetorical effigiation: a simulation of moral nearness and ontological grounding where none may exist. Deixis, then, must not be understood merely as spatial or temporal indication—it is the contextual enactment of moral position, and in distorted discourse, it becomes a key site of typophoric drift and ontological manipulation.

Exophoric reference, refers to entities outside the discourse itself—things in the shared environment of speaker and hearer. It draws from physical, social, or situational context to anchor meaning (e.g., “Look at that,” “She’s here now”). Exophora connects language to empirical immediacy but does not inherently carry moral or ontological weight—unless paired with deictic or typophoric framing.

In contrast, endophoric reference, anaphora and cataphora, refers back to or forward, respectively, within the discourse itself—e.g., "this idea" or "the above claim." It ensures textual cohesion but does not claim moral space. Deixis, then, becomes the ethical edge of pragmatics: it does not merely refer—it aligns.

Beyond exophora and endophora lies a third class of reference: typophora—a gesture not to objects or clauses, but to ontological kinds. Typophoric reference points to moral or metaphysical abstract categories such as justice, grace, betrayal, or righteousness. These references are assumed to be real, morally weighty, and culturally intelligible—even when they are fabricated.

Typophora functions as conceptual deixis. It does not say where something is or what text it links to, but what kind of thing is being invoked. It creates the impression of ontological substance—whether that substance is covenantally grounded or not. A phrase like "this justice" does not refer to a specific law or event; it presumes a moral kind, ontologically real and rhetorically available.

We distinguish two forms:

Onto-typophoric reference: grounded in divine reality (e.g., “This is My beloved Son”).

Semiotic-typophoric reference: culturally constructed, symbolically potent but ontologically severed.

In secular discourse, semiotic-typophora is routinely abused. Phrases like "our truth," "this moment," or "these rights" blend deictic familiarity with onto-typophoric presumption. They simulate shared conviction while concealing ontological fraud. The language is stable; the referent has shifted.

This is effigiation via deixis—the rhetorical simulation of divine categories without their divine warrant. Terms like “grace,” “freedom,” or “justice” are re-used as moral tokens while referring to altered or emptied content. These become pseudo-tokens—linguistic acts that masquerade as ontological instantiations.

By contrast, Scripture models typophoric integrity: “This day I set before you life and death” (Deut. 30:19), or “This hope we have as an anchor of the soul” (Heb. 6:19). These refer not to ideas but to divinely revealed kinds. In biblical deixis, the demonstrative is a theological claim.

Deixis is not grammatically innocent. It functions as a moral act—positioning speaker and hearer within a perceived reality. When combined with typophora, it becomes a high-stakes gesture: it either returns to ontological truth or embeds pseudo-instantiations into moral discourse. In discerning deixis, one must ask not only what is meant—but who authorizes it and to what kind it returns. Only in covenantal grounding does deixis serve truth. Otherwise, it initiates the linguistic collapse of moral reference.

Though not primary pillars of pragmatic meaning, relevance, ostension, and intention function as filters that govern how components like deixis, implicature, and explicature are shaped, received, and morally navigated. In a relational-covenantal model of language, these are not merely cognitive tools—they are ethical instruments. They reflect not only how meaning is perceived, but how it is morally positioned.

Relevance governs what is foregrounded, downplayed, or excluded in discourse. It determines what the speaker offers as central, and what is treated as incidental. But this is not merely a matter of efficiency—it is an act of moral framing: What is made relevant in discourse reveals what is honored in the heart.

Ostension refers to the act of manifesting importance: what the speaker gestures toward as worthy of focus or response. This may occur through repetition, stress, placement, or contrast. In theological terms, ostension is a typophoric gesture: it not only directs attention, but promotes a kind—implying, “This is the sort of thing that deserves assent, emotion, or allegiance.” Ostension is therefore not neutral. It simulates ontological gravity. And when misused, it becomes a tool of discursive effigiation—projecting a pseudo-type with moral pressure but no divine warrant.

Intention refers to the aim behind the utterance—what the speaker wills to be received, or seeks to instantiate through their speech. This is not reducible to psychological desire. In a covenantal frame, intention is a moral vector. It either seeks fidelity to God's reality, or it functions as a volitional simulation of meaning for manipulative ends.

If language is covenantal, then these filters—relevance, ostension, and intention—are not stylistic tools but moral tests.

The speaker is accountable: not only for the content of their words, but for the moral frame they construct, the kinds they emphasize, and the will they extend through speech. To speak is not only to signify.It is to propose a world. And to determine, by emphasis and aim, whether that world reflects truth—or effigiates rebellion.

Presuppositions are the backgrounded unstated assumptions embedded within an utterance—assumptions that must be accepted as true for the statement to function. Unlike assertions, which present claims for evaluation, presuppositions bypass argument and implant discursive commitments beneath the surface of communication. For example, the question “Have you stopped lying?” presupposes prior dishonesty. If the assumption is absorbed—even unconsciously—the moral topology of the exchange has already shifted.

While presuppositions are often grammatically triggered—via change-of-state verbs (stop, begin), definite descriptions (the king of France), or factive verbs (know, realize)—their real power lies in ontological smuggling. They introduce culturally normalized assumptions about identity, morality, rights, or metaphysics—often without naming them explicitly. These assumptions do not merely shape perception; they simulate ontology. A successful presupposition implants not only a claim, but a typological template—a “kind”—that, once accepted, reorients the moral field. The hearer begins to treat a pseudo-type as real, and any verbal expression of it as a pseudo-token. This is a form of discursive effigiation—truth is not argued, but presumed into being.

Many presuppositions rely on typophoric reference: they gesture toward abstract, often moral categories that are not grounded in divine revelation, but assumed to carry covenantal weight. Phrases like “They fought for equality” or “We support reproductive justice” smuggle in semiotic-typophoric referents like equality, justice, or choice, as if these are fixed ontological types with shared moral legitimacy. In reality, such terms often function as pseudo-types—familiar-seeming but ontologically fabricated constructs, structurally recognizable yet covenantally inverted or severed from their biblical anchors. The rhetorical effect is coercive: the speaker establishes a moral topography, and the hearer is placed within it, usually without realizing that a semantic relocation has occurred.The grammar remains benign, but the ontology has shifted.

In this way, presuppositions operate not as cognitive efficiencies, but as cultural-linguistic substructures. They reconfigure discourse at the level of assumed truth, rather than examined claim. They perform semantic realignment without conscious consent—producing discursive pseudo-instantiations that bypass the Divine Double Prerogative. Scripture, by contrast, calls hearers to expose and test assumptions. Jesus’s rhetorical questions—“Why do you call Me good?”, “Have you not read…?”—disrupt presupposed moral legitimacy and force ontological realignment. Paul’s epistles do the same: they interrogate hidden frameworks and re-anchor them in divinely revealed onto-typophoric categories—righteousness, grace, sonship—not merely as doctrinal ideas, but as real ontological kinds, covenantally instantiated and morally binding. Presupposition is not a neutral feature of grammar—it is a moral act. To absorb a false presupposition is to participate in a simulated ontology. It is to accept an ungrounded kind—to bend one's moral compass toward something God has not named or defined.

The interpretive task, then, is vigilance: What typophoric structures are being assumed? Do they return to a real ontological type, as revealed by God? Or do they serve to fabricate types, to install simulated meaning with moral weight but no divine sanction?

This is not merely a matter of discursive hygiene. It is a matter of spiritual fidelity.

Implicature refers to meaning that is implied but not explicitly stated—arising not from the literal content of an utterance, but from what the speaker expects the hearer to infer based on shared norms. Rooted in Grice’s cooperative principle, it relies on culturally internalized expectations of politeness, relevance, and conversational coherence.

For example, “It’s getting late” may imply “We should leave now.” The meaning is inferred, not asserted.

While implicature allows for relational subtlety, it also enables moral evasion: a speaker may exert normative pressure while avoiding declarative responsibility. This is especially potent in public discourse, where implication becomes a tool of semantic coercion:

“That’s not a very inclusive opinion.”

→ Implies: “You are morally deficient” or “You threaten communal virtue.”

Here, the burden of moral inference shifts to the hearer, who—motivated by internalized fear of exclusion—fills in the ethical logic. The speaker escapes direct accountability.

This dynamic intensifies when implicature works alongside exophoric deixis (“we,” “now,” “this”) and typophoric reference (justice, freedom, inclusion). These familiar terms operate as pseudo-types, simulating moral weight while bypassing ontological grounding. In such cases, implicature functions as a delivery system for effigiation—performing the appearance of moral truth while covertly installing counterfeit categories. The result is discursive pseudo-instantiation: a suggestion that behaves as an ontological claim, but carries no covenantal sanction. In such cases, implicature becomes a form of semantic coercion—a shadow grammar of persuasion that simulates moral conviction while bypassing covenantal grounding. It exploits the residue of divine types, refilling them with ideological consensus. What remains is not truth—but influence detached from integrity.

In contrast, biblical implicature operates within a framework of revealed ontology and covenantal coherence. When Jesus says, “He who hath ears to hear, let him hear” appears as a covenantal summons in Matthew 11:15; Matthew 13:9; Mark 4:9; Luke 8:8; Luke 14:35; Revelation 2:7, 11, 17, 29; 3:6, 13, 22—He implies a call to spiritual discernment, not emotional compliance. He invites—He does not manipulate.

Prophetic implicature likewise implies judgment, restoration, or repentance, but always grounded in divinely revealed types—righteousness, holiness, mercy, covenant. These are not semiotic-cultural rhetorical gestures but onto-typophoric referents, morally binding and ontologically true. Here, implicature is weighty but faithful—a mode of invitation within the bounds of truth.

To discern implicature rightly is not merely to interpret the unsaid—but to test the ontology beneath it. The hearer must ask:

What typophoric category is being implied? Is this a faithful extension of a divinely revealed type?

Or a rhetorical installation of a pseudo-type?

Is the speaker guiding toward moral clarity—or manufacturing consensus?

At its best, implicature allows speech to transcend the literal in service of relational wisdom. But in an age detached from truth, it becomes a vehicle for plausibility without proof, persuasion without grounding, and influence without integrity. Implicature must therefore be judged not only linguistically, but morally and ontologically.

Explicature refers to the surface meaning of an utterance—what appears to be explicitly stated. Yet this surface is always shaped by lexical framing, contextual assumption, and typophoric drift. Though such speech presents as transparent—“It’s clearly stated”—this clarity is often deceptive. Terms like equity, freedom, or inclusion appear stable, yet their underlying referents may have shifted. The token remains; the type is displaced.

Explicature thus becomes a preferred vehicle for discursive simulation. It lends moral weight to statements whose referential grounding has eroded. Phrases like “this justice demands action” appear lucid, but clarity itself becomes camouflage. The audience receives not just a proposition, but a pseudo-instantiation—an effigiated moral category wrapped in grammatical fluency. In such cases, clarity functions not as truth-bearing revelation but as semantic sleight of hand—where precision reinforces illusion.

Clarity, then, is not innocence. It must be judged not by syntactic competence but by ontological return: Does the term trace back to a covenantally grounded type, or has it been re-coded by cultural consensus? In a disordered linguistic ecosystem, even fluency can be fraudulent. Explicature does not absolve discourse of moral accountability—it intensifies the need for ontological discernment.

While explicature and implicature define the semantic bounds of meaning, another register operates beneath them—a scalar and affective dimension that shapes how language is perceived, felt, and morally registered. This includes not only prosody—tone, rhythm, inflection—but also bodily expression, ranging from paucity to verbosity, and from posture to gesture. These elements do not merely ornament speech—they participate in its moral valence.

On one pole lies paucity: restrained speech, intentional silence, or ellipsis. In high-context moral discourse, what is unsaid may signal reverence, grief, dissent, or invitation. A whispered pause may carry more moral weight than an overt declaration. At the other pole lies verbosity: overarticulation that may clarify—but also obscure, overwhelm, or dominate. Rhetorical saturation can simulate moral seriousness while masking ontological vacuity.

Prosody governs this continuum. The same utterance—“I understand,” “That’s fine,” “Do what you want”—may express assent, resistance, irony, or submission depending on rhythm, tone, and emphasis. Prosody renders moral posture audible, often registering more deeply than the words themselves.

Even without words, the body speaks. Facial tension, a bowed head, crossed arms, or spatial proximity—all convey moral stance. These are not merely “nonverbal cues,” but kinaesthetic signs that disclose (or distort) the speaker’s alignment with truth. A gesture may reveal humility—or cloak resistance. A posture may express reverence—or simulate sincerity.

The embodied register can either reinforce propositional fidelity or expose performative fracture. A morally sincere utterance finds coherence in voice, tone, and gesture. By contrast, discursive simulation often entails affective dissonance: the body says what the proposition cannot sustain.

Expression, then—whether tonal or bodily—is never neutral. It participates in covenantal meaning. It may amplify sincerity or mask simulation. It may disclose presence—or orchestrate compliance. This scalar register invites discernment not just of what is said, but how it is offered, and whether it resonates with moral truth or emotional coercion.

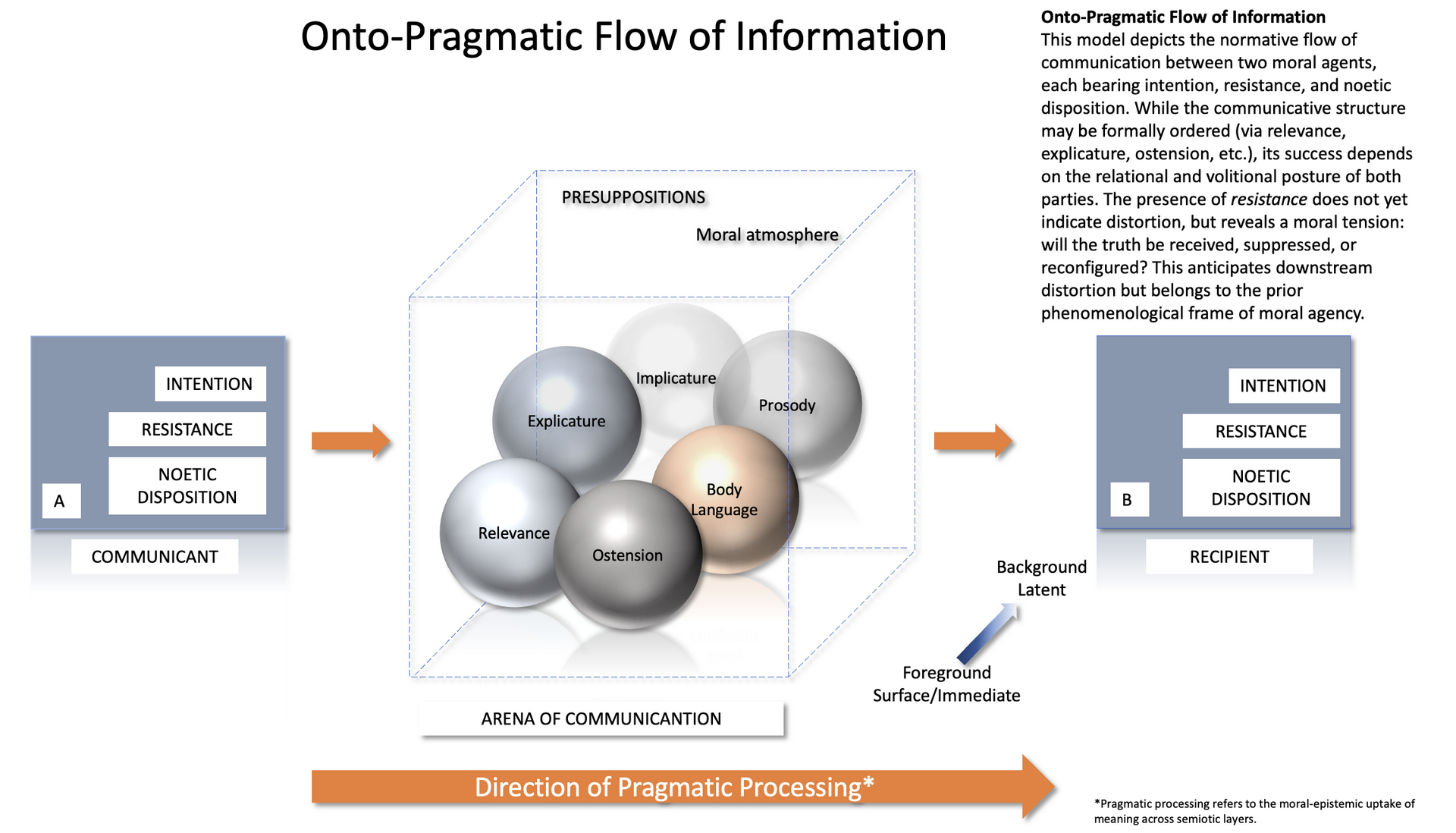

The Onto-Pragmatic Flow of Information:

This model visualizes the moral and semiotic structure of communication between two agents. It traces how intention, resistance, and noetic disposition govern the uptake of meaning across multiple semiotic layers—from explicit relevance and ostension to more latent forms such as implicature, prosody, and body language. Communication unfolds within a morally charged atmosphere, where what is said is inseparable from how—and whether—it is received.

Structuralism sought to explain meaning through systems of difference, where signs gain significance not by inherent content, but by contrast within a symbolic system. While this helps describe how words function within language, it induces crisis when applied to pragmatics. If all meaning is relational and no ontological anchor exists, then deixis, presupposition, and implicature remain structurally active but morally adrift. The framework persists, but it points to nothing. What results is semantic form without substance—gestures without grounding.

Without ontology, structuralism cannot distinguish between a true onto-typophoric referent—which gestures toward a divinely delimited kind—and a pseudo-type, sustained only by repetition or social inertia. Terms like justice or grace are emptied of ontological force and recycled as rhetorical placeholders within a closed symbolic economy. Deconstruction radicalizes this collapse. It suspends all closure, displaces all centers, and insists that reference is always deferred. Meaning is not denied—but debased into infinite contingency. Deixis becomes performance, presupposition becomes ideological entrapment, and implicature becomes an interpretive echo chamber. The result is pragmatic nihilism: speech with no referent, persuasion without truth, and language that drifts without covenantal gravity.

This is where the Deontic–Modal (DM) Unit becomes essential—not merely as a decoder of discourse, but as a covenant-bound moral filter. The DM Unit evaluates: not just what is said, but whether the utterance returns to an ontologically authorized type.

It discerns: whether deixis invokes a true moral “we” or simulates communal authority; whether presuppositions are covenantally grounded or ideologically smuggled; whether implicature reflects divine invitation or discursive coercion. When onto-typophoric reference is hijacked—when words like freedom, justice, or inclusion carry rhetorical force but lack covenantal content—the DM Unit resists. It refuses the effigiated referent, and reasserts ontological fidelity.

Language is not a neutral tool of communication—it is a relational instrument, accountable to the God who speaks truth and demands truth in return. If language is covenantal, as Scripture affirms, then clarity and integrity are not stylistic preferences but moral imperatives.

Every pragmatic component—deixis, presupposition, implicature, explicature—must be anchored in God’s ontological reality. These do not merely convey meaning; they carry covenantal weight. A term may appear clear, but if it gestures toward a pseudo-type, it participates in simulation, not truth.

Christ never preserved ambiguity for rhetorical advantage. He spoke clearly, faithfully, and without ontological drift—even when it cost Him favor. Likewise, clarity is not about fluency but fidelity. To obscure truth under polished speech is not strategic—it is betrayal.

Language cannot generate truth from within its own system. It must either return to being or simulate it. Severed from ontology, pragmatics becomes a semiotic game—mimicking moral gravitas while hollowing out its referent.

Especially in typophoric constructions, language can project being rather than reflect it—as if naming makes real what God has not authorized. This is the essence of effigiation: the pseudo-instantiation of meaning through linguistic performance, usurping the Divine Double Prerogative by naming without warrant.

True signs arise from correspondence to being, not from consensus. Being is not discovered through language—it is disclosed by God and upheld through covenantal fidelity. To speak rightly is not an act of stylistic clarity, but of ontological submission. This is not weakness—it is worship.

Each pragmatic gesture must be tested—not merely for coherence, but for correspondence to (relationally disclosed ontological) truth. Deixis must point to a covenantal moral center, not simulate communal authority. Misused deixis displaces reality under the illusion of shared position. Presupposition must face divine disclosure. What is assumed is not innocent—it makes a claim on reality, which belongs to God. Implicature must align with Christ’s communicative character. Subtext that trades in shame, urgency, or crowd psychology violates the ethics of invitation. Explicature, however fluent, must return to true ontological types. Sacred terms like justice, freedom, or grace must not be repurposed to hollow forms. Otherwise, clarity itself becomes semantic coercion: rhetorical polish masking effigiated content.

In all cases, the question is not simply: “Is it persuasive?” but: “Is it true in the presence of God?”

This is where the Deontic–Modal (DM) Unit becomes essential. It is not merely a cognitive device but a Spirit-enabled moral faculty that discerns: what kind a word invokes? Whose authority it presumes? Whether it corresponds to a divinely instanced type. The DM Unit resists effigiation. It refuses to accept rhetorical form in place of revealed substance. It discerns between covenantal reality and discursive simulation. It is conscience tethered to being, the soul’s resistance to semiotic seduction.

Truth is not emergent, inferred, or assembled by consensus. It is relationally bestowed, ontologically grounded, and ethically discerned. Faithful discourse flows from, and returns to, the living God—who alone defines what a word like this or we is permitted to reference. To interpret rightly is not to decode grammar alone, but to discern the covenantal reality behind linguistic form.

To speak truly is to signify only what God has made real. To fabricate referents is not expression—it is rebellion. And to listen rightly is to test: is this word echoing what is, or projecting what is not?

In the end, language is not neutral—it is morally loaded. Every utterance, every interpretive act, either returns to covenantal truth or cooperates with simulation. Both speaker and hearer stand accountable—not merely before each other, but before the One who defines being. Deixis, implication, assumption, and typophora—all of these frame reality. But reality is not constructed; it is received. To speak, to interpret, to affirm—is to either align with what God has made real, or to participate in its effigiated counterfeit. In such a world, words do not simply inform. They position. They reveal our posture before the Truth.

The central site of discursive manipulation is typophoric reference. Unlike grammatical deixis or internal textual cohesion, typophora enables the speaker to invoke abstract moral categories without defining or defending them. These terms function not as neutral signifiers, but as semiotic decoys—familiar in form, yet ontologically displaced.

Typophora is the primary site of manipulation because it invokes abstract, morally weighted categories without requiring definition or defense. These terms—justice, grace, inclusion—are not neutral; they carry sacred familiarity while often being ontologically displaced. What results is not drift, but semantic substitution: counterfeit meanings are installed beneath intact tokens. This is effigiation—the projection of moral authority through forms that no longer correspond to divine kinds.

Though less malleable than typophora, deixis and endophora also enable manipulation. Deictic terms like “we,” “now,”or “this” can simulate urgency or consensus by locating the speaker within an assumed moral frame. Endophora, while structurally internal (e.g., “this principle”), may be rhetorically reframed, redirecting its emphasis without alerting the hearer. These forms appear stable—but stability here is grammatical, not ethical.

Symbolic media—film, music, monuments—reconfigure the referential field of deixis and typophora. Through sensory saturation, they rewrite what terms like “our land” or “freedom” mean, without altering the words themselves. The result is affective plausibility: typological redefinition becomes intuitive. Moral manipulation now occurs not through argument, but through immersion.

All referential layers are vulnerable to distortion, but not equally. The farther a term is from empirical verification and the more morally charged it is, the greater its susceptibility to hijacking. Typophoric references—abstract yet emotionally resonant—become ideal carriers for semantic effigiation: they preserve form, simulate weight, and bypass scrutiny. They are most likely to be mistaken for truth because they feel self-evident, not because they are covenantally grounded.

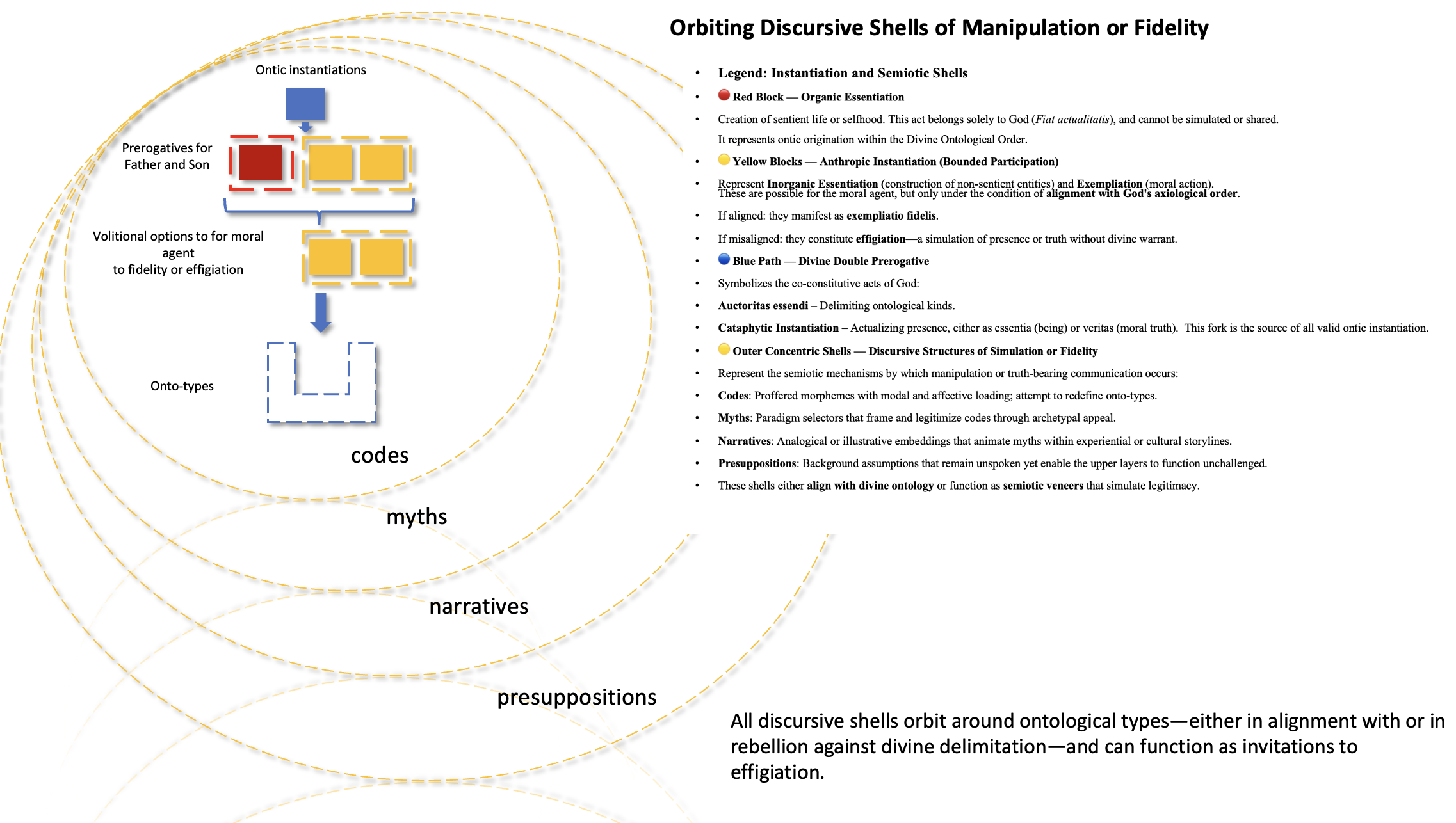

Codes are not mere words—they are performative tokens that simulate divine prerogative. Infused with affective charge and moral urgency, codes like “inclusive” or “equity” bypass argumentation. They function as typophoric imperatives, demanding assent through simulated righteousness. Their force is not rational but emotive—and their authority is often assumed rather than earned.

Myths provide the archetypal architecture for codes, presenting cultural templates like “the liberator,” “the victim,” or “the cleansing catastrophe.” These are not conclusions—they are premises posing as moral truths. Narratives then embody these myths in experiential form, making the code emotionally necessary. Through repeated plots of awakening or rebellion, what is ideological becomes existential. The result: the counterfeit becomes intuitively good—felt before it is questioned.

Presuppositions are the hidden architecture. They stabilize the whole discursive tetrad—codes, myths, narratives—by operating beneath scrutiny. Once installed, they define the moral landscape without ever surfacing as claims. Together, this tetrad constructs a semantic illusion: a world where ontological fraud feels like virtue. For example, the code “equity” may be framed by a myth of justice-as-redemption, animated through a narrative of reparation, and grounded in the silent presupposition that justice equals parity. None of these require defense; they operate as moral axioms.

Discernment is not merely about resisting error—it is about exposing simulation. We are not deceived by outright contradiction, but by familiar forms reinhabited by falsehood. To recover clarity, one must unmask the function: Is this term operating as a code? Is this storyline animating a myth? What presupposition is being smuggled as self-evident?

A summary is presented below, illustrating the concepts elaborated.

A case-study on codes, myths and narratives and presuppositions is provided for conceptual clarification here .

Pragmatic distortion inherits its structure from the semiotic field. The same conflative operations that, in language and culture, merge distinct ontotypes—syncretic conflation at the conceptual level and homonymic conflation at the lexical level—reappear within speech as inferential shells: utterances whose implications mimic moral coherence while masking ontological rupture. In conversation the merger is no longer between symbols but between motives and meanings. The effect is identical, however: a simulated unity that persuades but does not correspond to truth. Thus, pragmatic manipulation can be read as the personal, situational expression of the same counterfeit logic that governs semiotic effigiation.

Diagram above illustrate that all discursive shells orbit around ontological types—either in alignment with or in rebellion against divine delimitation—and may function as invitations to effigiation. Whether through redefined codes, archetypal myths, analogical narratives, or backgrounded presuppositions, the manipulation of meaning is ultimately the manipulation of being.

The most potent forms of linguistic manipulation do not occur at the level of syntax or local deixis, but at the level of typophoric reference—where language invokes abstract, morally charged categories whose meanings are presumed, not proven. While deixis (“we,” “now,” “this”) can simulate urgency or consensus, typophoric terms like grace, justice, or equity operate with borrowed gravity: they retain covenantal form while severing covenantal content. Their referents shift—but their moral force remains, allowing counterfeit meanings to pass as sacred consensus.

This drift signals a larger phenomenon: the systematic redirection of discourse itself. Through mythic frames, affective repetition, and symbolic saturation, even concrete referents are culturally reprogrammed. Words remain—but their meaning is pre-curated, their range of interpretation narrowed. The result is not linguistic failure, but discursive capture: where persuasion replaces truth, and speech aligns with engineered norms rather than revealed reality.

We now turn to one of the primary mechanisms of this process: the Overton Window. It offers a lens for understanding how typophoric categories are manipulated within staged boundaries of acceptability—where language is no longer a vehicle of communion, but a tool of control.

With the key pragmatic mechanisms now laid bare—deixis, presupposition, implicature, and explicature—we are positioned to step beyond the sentence and into the wider arena of discourse. Language does not merely operate clause by clause; it frames realities, excludes alternatives, and guides moral interpretation through extended patterns of emphasis, omission, and association. What is highlighted and what is hidden, what is positioned as natural and what is rendered unthinkable—these are not neutral operations. They constitute discursive manipulation through framing, binary pressure, reciprocal exclusion, and referential saturation. For those seeking a structured diagnostic method, the Onto-Discursive Analysis (ODA) Tool—provided in the Appendices —synthesizes these insights to expose such distortions and recover interpretive fidelity. We now turn from structural exposure to spiritual confrontation: a deep-dive into presuppositional warfare, where discourse becomes the battleground of allegiance, deception, and theological resistance.

Summary

This section has shown how Pragmatics is not merely a question of tone or intent—it is the battleground where discourse either serves truth or subverts it. Deixis can redefine moral boundaries; presupposition can smuggle in ontological claims; implicature can pressure assent without clarity; and typophora can simulate moral absolutes by mimicking the structure of divine categories. The cumulative effect of these pragmatic maneuvers is not just linguistic confusion but ontological displacement—a world in which the moral shape of meaning is recoded by rhetoric. In such a context, discernment requires more than syntactical parsing; it demands an ontologically anchored conscience, responsive to divine categories, and capable of resisting typological fraud. The next section traces how this displacement becomes normalized through public discourse, showing how the semantic battlefield becomes social architecture—and how the thinkable is systematically redefined.