This section examines the collapse of meaning in semiotics and the possibility of its restoration through a biblically grounded relational ontology. Secular semiotic frameworks—particularly those informed by structuralism and post-structuralism—detach signification from being, reducing language to a system of self-referential signs governed by cultural codes and ideological interests. In doing so, they undermine the possibility of fixed reference, stable identity, and moral coherence. By contrast, the relational-biblical model insists that language is not autonomous but covenantally ordered: it mirrors being, not constructs it. Signs, in this view, are not arbitrary conventions but morally accountable acts of correspondence, governed by the Creator’s prerogative to define and instantiate reality. This section will demonstrate that the corruption of language is not merely a semantic drift but a metaphysical rebellion—and that the restoration of semiotic integrity is both a theological imperative and an eschatological promise.

Semiotics is the study of signs and the meanings they carry. A sign may be a word, image, gesture, symbol, or any medium through which meaning is conveyed. In secular theory, signs are typically understood as arbitrary linkages between a signifier (form) and a signified (concept), deliberately excluding the referent—the actual entity in the world. This severing permits meaning to float free from being, redefined by social utility rather than metaphysical obligation.

Modern semiotic theory—emerging from the structuralist and poststructuralist traditions—rests on a foundational assumption that language is arbitrary, culturally constructed, and historically contingent. Ferdinand de Saussure, often regarded as the father of semiotics, famously proposed that the relationship between the signifier (the sound or symbol) and the signified (the concept) was purely conventional (Saussure 1983). Later theorists such as Roland Barthes (1972) extended this framework to argue that signs operate within ideological systems, reinforcing the codes and myths of dominant culture. For post-structuralists like Jacques Derrida (1976), even these structures collapse under deconstruction, as meaning endlessly defers and never settles—language is an infinite play of signifiers with no stable center. (See `footnote on terminology).

Mainstream semiotics, whether in the structuralist lineage of Saussure or the triadic model of Peirce, fails to provide ontological grounding for the referents it describes. While Peirce’s model allows that the "object" may be abstract, it offers no criteria for distinguishing whether the referent is ontologically real or merely conceptual. As a result, terms like truth, justice, or identity may be referenced semantically but lack metaphysical validation. This ontological severing generates four critical consequences: (1) floating signifiers, where terms drift semantically without ontological anchor; (2) referential relativism, where abstract concepts become ideologically contingent; (3) moral ambiguity, where the same signs may justify contradictory ethical postures; and (4) infinite interpretability, where meaning never terminates in a stable referent, only in recursive interpretation. These sequelae expose the systemic vulnerability of all signification divorced from ontological truth: a n ontological rebellion that denies the moral obligation to signify what is true according to God. Without a vertical referential axis rooted in divine instantiation, semiotic structures collapse into simulation. What is needed is not a new syntax or semiotic code, but a recovered metaphysical referent—truth as revealed, not constructed.

In this relational-ontology framework, signs—whether tangible or abstract—cannot be neutral. They are covenantal gestures: entrusted to moral agents for the faithful transmission of meaning, accountable to the Creator, and anchored in ontological reality. Signs must correspond to divinely defined referents, not merely to shared convention or affective resonance. To manipulate signs is not merely to miscommunicate—it is to risk ontological distortion. Language, therefore, is not merely expressive or cultural—it is covenantal. When rightly ordered, signs do not merely describe reality—they bear witness to it. This framework insists that semiotics cannot stand alone. It is not a self-contained system of relational signs, but a dependent structure—derivative of epistemic access and governed by ontological grounding. When the hierarchy is inverted—when signs are treated as self-originating—truth becomes vulnerable to simulation.

This is the essence of effigiation: not mere misrepresentation, but the fabrication of false presence—the simulation of what God has not instantiated. Thus, the restoration of semiotics begins with reordering. Language must be re-situated within an ontological cascade:

Ontology → Epistemology → Semiotics

Only in this order can signs regain integrity, meaning remain coherent, and moral truth be preserved. What follows is a confrontation with secular semiotic paradigms—and the proposal of a relational-theological alternative in which signs are covenantally bound to the realities they name, and accountable to the One who gives both.

Throughout this framework, semiotic analysis assumes not a neutral communicative field, but one in which both the communicant and the recipient are morally mal-aligned and ontologically dislocated. Neither occupies a privileged position of sanctified clarity. The codes they wield, the tropes they invoke, and the signs they interpret operate within a compromised domain where susceptibility to distortion is bilateral. The pseudo-instantiation of moral authority—whether through manipulative signalling or passive complicity—exposes the shared vulnerability of moral agents operating without ontological realignment. Thus, semiotic manipulation is not merely something done to another; it is an inter-creaturely dynamic in which both parties may be deceivers, deceived, or both.

The biblical worldview presents a radically different picture. Language is not an emergent byproduct of human society, but a divinely bestowed capacity at the beginning. Adam did not learn to speak with the Creator; he was able to speak from his creation. In Genesis 2:19–20, Adam is taxonomically commissioned to name the creatures—not as a creative act of invention, but as a privilege to be exercised with discernment and recognition. Semiotically speaking: the types had already been formed by God; Adam's task was to assign names to instantiated tokens, affirming their created essence.

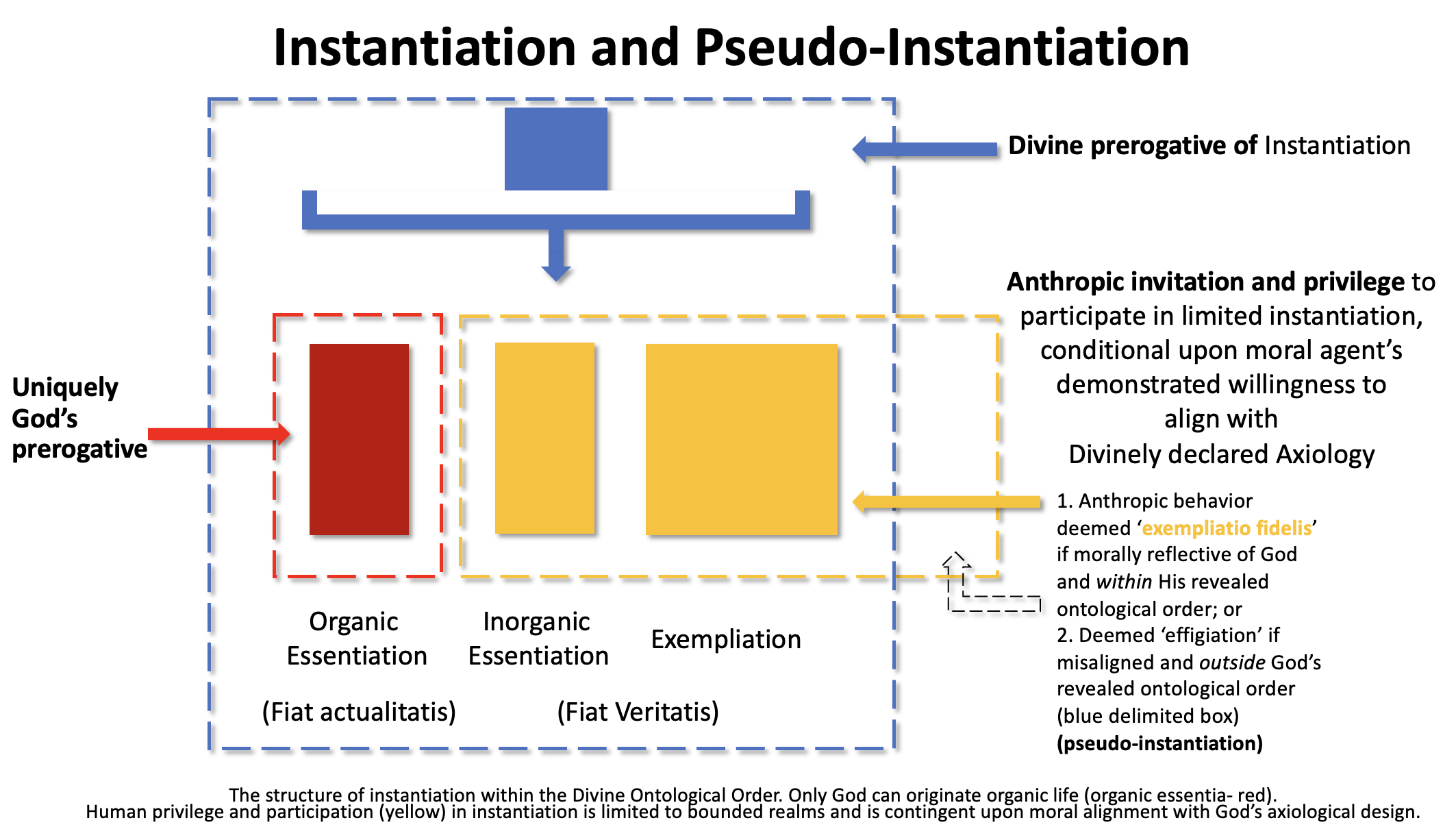

This affirms what we define elsewhere as the Divine Double Prerogative: only God may delimit ontological types (auctoritas essendi), and only God may authorize instantiations of those types (instantiandi). Adam’s naming does not invent reality—it responds to what has already been defined and instanced.

In this sense, Adam functions as a steward of ontological classification. The freedom of the act of naming is rooted in relational, reverent, and covenantal propriety and morality—not in arbitrary or random assignment.

In philosophical terms, we might say that the 'type' corresponds to ontology, while the 'token' corresponds to ontic instantiations of being. There is a correspondence between ontological type and semiotic type, but not an equivalence; the sign must align with being, but it does not constitute it. This distinction preserves the integrity of identity while allowing for multiplicity.

The theology of Van Til even has its own pertinent terminology that maps onto these delineations: ‘cataphatic’ and ‘anaphatic’ expressions— the former referring to positive features of an object, the latter referring to its delimiting boundaries. These correspond respectively to the ontic-token and type-ontology schema.

To name rightly was a morally upright act—a onto- typophoric alignment with reality. It was to gesture toward a God-defined type in humble fidelity. Thus, naming and signification were never linguistically neutral—they were acts of ontological stewardship. Speech was intended to mirror being, not construct it. This moral-ontological alignment grounds our model of language not in use, but in ontological correspondence, governed by relational and covenantal integrity.

The fall did not introduce language, but rather corrupted its use, introducing deception, obfuscation, and disalignment between sign and referent (cf. Genesis 3).

The fall did not create semiotics; it corrupted onto-typophoric fidelity. What was once reverent recognition of divine types became a tool for inversion and simulation—what we will later identify as effigiation.

In a properly ordered ontological framework, negative (anaphatic) delimitation is more fundamental than positive (cataphatic) description. This is because the identity of a given entity or onto-type is not constituted by the sum of its observable characteristics, but by the boundaries set by God which constrain what it cannot be. These boundaries reflect the ontological type’s divinely assigned moral, modal, and existential limits.

To define marriage ontologically: one must first reject false instantiations (pseudo-types) such as union without covenant, covenant without complementarity, or union for transactional gain. Only then can one meaningfully affirm its cataphatic features: covenantal, binary, procreative potential, spiritually symbolic, etc.

The confusion of tongues at Babel (Genesis 11) is often misread as a purely punitive act. However, within a relational and eschatological framework, it is more accurately understood as a redemptive intervention. God fractured a unified linguistic system not merely to scatter humanity geographically, but to interrupt its capacity for coordinated typophoric rebellion—the false projection of legitimacy through unified speech divorced from divine authorization.

At Babel, a singular semiotic regime was being mobilized to construct a name, a tower, and a city in defiance of divine delimitation. The project was not only architectural or imperial—it was semiotic, driven by an ontologically unauthorized use of naming, coding, and symbolic unification. The divine response was not to destroy language, but to diversify it—to prevent the ontological consolidation of rebellion by fracturing the discursive system that enabled it.

Language multiplicity thus becomes a theological safeguard against typophoric totalitarianism—against the possibility of projecting a unified pseudo-order upon the world without reference to God.

The imposition of multiple tongues served multiple redemptive functions: as restraint: it delayed the full consummation of human self-deification; as divine disruption: it interrupted the ontological fraud of a counterfeit kingdom; as theodictic* preparation: it carved space for the eventual gathering of all nations under a restored, sanctified Logos (cf. Acts 2, Rev. 7:9).

This is not the loss of meaning, but the multiplication of signification under divine control. It is not linguistic entropy—it is semiotic judgment for the sake of future reconciliation. In light of this, Babel marks not the fall of language, but the protection of ontology from unified distortion. It affirms that God alone may authorize the unity of speech, and that no typophoric coherence can be morally safe unless it is grounded in divine instantiation.

Without the theological grounding of divinely delimited types and authorized tokens, the secular semiotic system unravels. In the absence of a fixed referent, codes drift, tropes invert, and myths recode ontology through analogical saturation. Ideologies then arrogate the power to invent pseudo-types and mint pseudo-tokens, generating an illusion of legitimacy without ontological grounding. In short, the linguistic hierarchy collapses: from ideological paradigms to semantic codes; from typophoric gestures to tropological simulations; down through syntagms, articulation, and morphemic drift. At every level, the absence of type-delimitation produces a discursive simulation of authority. In practice this collapse is prosecuted through presuppositional warfare—typophoric distortion, binary pressure, narrative layering, and semiotic overload—tactics analysed in detail in the following Pragmatics section.

Fixity vs. Integrity. This collapse, however, never alters a type’s fixity—the external, God-secured boundary that resists reassignment. What disintegrates is the type’s integrity—its internal moral and axiological coherence as instantiated in language and culture. Semiotic corruption fractures the creature’s participation in a kind, but it cannot breach the kind itself; the ontotype remains immutably anchored in divine prerogative even when its cultural representation is falsified. (See Ontology Part II for a detailed discussion of the characteristics of an onto-type).

When the type is no longer treated as fixed—morally or metaphysically—culture manipulates it through counterfeit codes and offers pseudo-tokens in its place. The genuine token remains ontically fixed, yet the discursive claim attempts to re-type it, projecting it as a different ontological category. This is not mere interpretive variation; it is an attempted act of ontological reassignment.

Such manipulation constitutes a pseudo-instantiation: a semiotic act that simulates the Divine Double Prerogative—defining what may be (auctoritas essendi) and instantiating it (instantiandi). It breaches the anthropic vocation to receiveand faithfully echo divine instantiation, replacing it with human self-authorization. This is the essence of effigiation: the simulation of instantiation, using signs to project a reality God has not made.

Language, once covenantally correspondent, now performs as discursive rebellion—falsely typophoric, morally weighted, ontologically void. The collapse is therefore not passive confusion but metaphysical insurrection: a rejection of God’s right to name and to make. Denying the fixity of being dissolves the foundation of truth, unmoors moral categories, and weaponizes meaning—not for discernment, but for domination.

A code is a symbolic structure that carries both surface denotations and underlying modal and affective connotations. It is not a neutral descriptor, but a proffered meaning—a cultural claim embedded with cues for how one should think, feel, and respond. In theological terms, a code is an attempted redefinition or re-framing of an ontological type (onto-type), often deployed apart from divine authority. It seeks to simulate ontological legitimacy by bypassing the anaphatic boundaries God has set for each type, and masking the simulation with emotional and modal plausibility.

A code, therefore, is typophoric: it gestures toward a (ontological) kind, claiming participation in a reality that may or may not be real. The moral status of a code depends entirely on whether the type it invokes is divinely delimited or fabricated.

Codes function as mediating structures between language and worldview. They either reflect God-ordained categories, or they simulate alternatives by redefining what counts as a “kind.” Crucially, codes often draw persuasive force not from logic but from supporting myths and narratives:

A myth provides symbolic justification—an paradigm-defining origin story that bestows moral gravitas.

A narrative offers emotional coherence—embedding the code in a lived or dramatized framework.

Together, these reinforce the illusion that the code is anchored in being, when in fact it may only be anchored in sentiment, politics, or ideology.

A pseudo-type may be logically coherent, psychologically resonant, or socially celebrated—but if it lacks divine sanction, it is a category of effigiation. It mimics the shape of an ontological type, but has no covenantal authorization behind it. This holds true not only for tangible categories (e.g., biological sex, kinship roles, nationhood), but also for abstract types such as truth, justice, or identity—concepts that carry real ontological weight in God’s order but are frequently simulated through ungrounded typophoric gestures. Abstract pseudo-types are especially insidious, as they cloak moral manipulation in the language of universal virtue while bypassing the divine referent entirely.

From pseudo-types arise pseudo-tokens: roles, identities, institutions, or symbolic persons that instantiate these illegitimate categories. These tokens are treated as if real, but they lack participation in any ontological type defined by God. Their discursive invocation becomes a simulated act of instantiation—a breach of the entrusted stewardship of the anthropic participation in instantiation, as discussed earlier.

These tokens are ontological forgeries. They may function with affective intensity and modal pressure, but they remain disconnected from the structure of reality. They are not misused symbols alone—they are claims to ontological authority without warrant.

This invocation of categories that carry moral and metaphysical weight, yet lack grounding in divine intention or covenantal recognition, is what we define as onto-typophoric projection: a gesture toward abstract types that simulate divine categories for persuasive or ideological ends.

In contrast, a true token in the relational-correspondent model is not merely a linguistic instance—it is an ontic manifestation of a God-defined type. Its legitimacy rests not in human recognition, but in divine authorship.

Having established the ontological function of code and its role in generating pseudo-types and pseudo-tokens, we now turn to its cultural mechanics—how code operates as the engine of onto-typophoric simulation in lived environments. The primary engine of ontological simulation is the code. A code is a culturally embedded structure that governs interpretation: it shapes how tokens are classified and how types are perceived. In a divinely ordered framework, codes function covenantally—reflecting, stabilizing, and transmitting meaning by aligning with God-defined ontological types. But within a self-referential or fallen framework, codes become typophorically creative: they no longer mirror reality—they manufacture it. Put simply, codes can effigiate (simulate instantiation) indefinitely — mutating sign-form while masquerading as ontological fidelity, eroding integrity while leaving the type’s fixity untouched.

In such an environment, the code does not passively signify; it actively simulates. Specifically:

Codes construct pseudo-types by organizing conceptual deviations into systematized categories that imitate real ontological kinds.

Codes project pseudo-tokens by giving symbolic and institutional weight to these illegitimate categories, treating them as morally binding.

Codes saturate the sociocultural domain, embedding these distortions into rituals, laws, educational norms, and psychological expectations—making the pseudo-type feel not only possible, but righteous.

Codes invert moral order by replacing divine revelation with cultural consensus and by substituting ethical clarity with affective coercion.

Each of these acts is typophoric—a gesture toward kindhood. But when the kind is not defined by God, the gesture becomes fraudulent. This is not an epistemic misfire, but a semiotic trespass. It claims prerogatives of ontological authorship while remaining severed from the Divine.

The result is a saturated pseudo-ontological environment: a discursive world that appears morally rich, but is metaphysically hollow. The signs feel weighted, the categories feel sacred, but the reality behind them has not been instanced. Meaning is no longer received; it is imposed. Ontological alignment is forsaken for cultural fabrication.

Beyond the instruments of distortion already examined—codes, tropes, myths, and legends—which for the sake of conceptual simplicity have been treated as attempts to effigiate a single ontotype, it is theoretically possible to project effigiation across two distinct ontotypes so that their boundaries appear to collapse. This higher-order simulation may be called syncretic conflation, when two categories are rhetorically merged into one composite shell, or homonymic conflation, when a single linguistic token is applied to opposing kinds so that they seem continuous. For instance, when liberty and license are spoken of as the same “freedom,” the token itself becomes the agent of homonymic conflation; when justice and compassion are re-cast as a single political virtue detached from their respective moral referents, the result is a syncretic conflation. In each case the merger exists only within discourse: it fuses descriptors, not realities. The ontotypes themselves remain inviolate under the Divine Double Prerogative, their distinctions merely veiled by the simulation of unity.

This prepares the ground for full effigiation—the simulated projection of presence without divine reference, which we will address in the next section. We reproduce the illustrative slide from before:

The reader is reminded that a pseudo-instantiation simulates one or more of these following features while lacking the rest; effigiation always fails the full seven-fold test of a Real Ontotype: Fixity – God-secured boundary• Integrity – internal moral coherence• Parsimony – ontological economy• Typological Convergence – recurring patterned instantiation• Modal Implication – limited, ordered possibilities• Telic Vector – intrinsic purposive direction• Divine Assignment – grounded in God’s prerogative. See Appendix D01for a more detailed discussion.

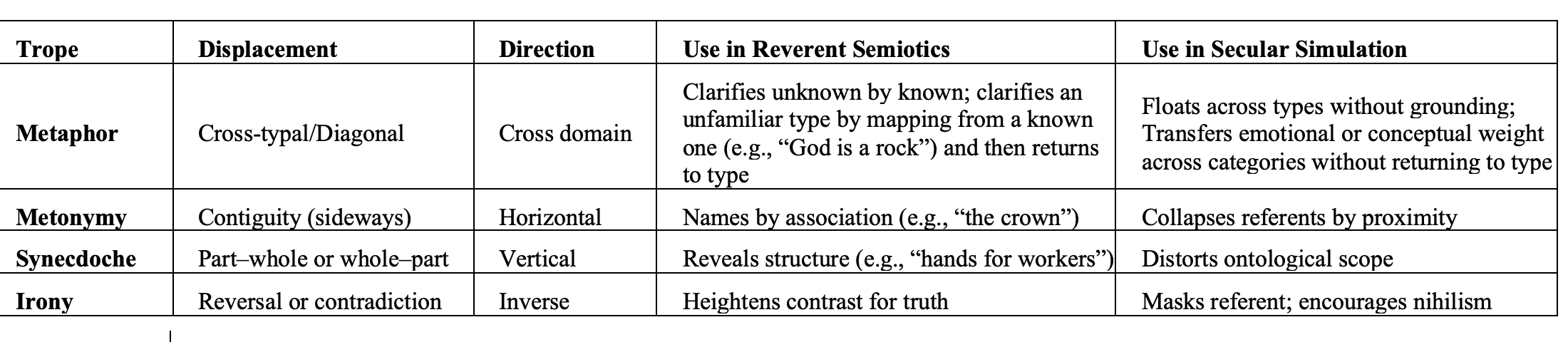

A central agent in typophoric simulation is the trope. In classical semiotics, a trope is a rhetorical or narrative figure that reassigns a token to a different semantic frame for effect or insight. The category includes metaphor (resemblance), metonymy (association), synecdoche (part-for-whole), and irony (inversion). In our ontological model, however, tropes are not merely stylistic—they are vehicles of typophoric redirection, with profound moral and metaphysical consequences.

In reverent usage, a trope is an epistemic bridge. It temporarily gestures from the known to the unknown—not to replace the type, but to clarify it. A faithful metaphor draws analogical insight while remaining morally obligated to return to the ontological type it sought to illuminate.

This return clause is what distinguishes analogy from simulation. A metaphor that never returns becomes an idol—a symbolic substitute that displaces the referent rather than reflecting it. When tropes are employed without this ontological humility, they become instruments of category distortion.

In secular semiotic systems, tropes often become permanent stand-ins for divine types. Metaphor is used not to illuminate a reality, but to escape it. There is no pressure to return to type, because no type is held as real. This is not poetic license—it is ontological equivocation masquerading as rhetorical depth. It enables the manipulation of categories under the guise of expression and weaponizes language against the moral order.

In this sense, every trope that refuses to return to its referent enacts a typophoric fraud. It postures as insight while enshrining inversion. The result is effigiation by analogy—a pseudo-instantiation built on a symbolic detour.

This is why, within the relational-biblical model, truthful speech is not merely a matter of lexical accuracy or literary elegance, but of ontological submission. Analogy is a gift only when it knows its place—to serve, not to substitute.

This progression from reverent analogy to typophoric fraud exposes the full arc of semiotic collapse. When the biblical cascade—Ontology → Epistemology → Semiotics—is reversed or ignored, signs still perform an epideictic function: they confront the soul with the appearance of meaning. Yet, absent covenantal grounding, that confrontation immediately triggers an elentic crisis—the will is exposed, forced either to yield to the fixed ontotype it has invoked or to suppress the truth and embrace simulation. In fraudulent systems the latter prevails: meaning detaches from being, knowledge becomes self-referential, and language turns performative rather than revelatory. The result is not mere miscommunication but ontological infidelity—tokens proliferate, types are fabricated, and tropes simulate presence where no divine instantiation exists. Only by restoring the hierarchy—truth grounded in being, knowledge formed through covenant, and language shaped by fidelity—can semiotics regain moral weight, epideictic integrity, and elentic honesty.

Beyond the code itself, semiotic manipulation deepens through the use of myths and narratives. These are not merely aesthetic or cultural features—they are typophoric reinforcement mechanisms, anchoring the code in structures of symbolic authority and emotional resonance. Together, they form the analogical scaffolding that normalizes pseudo-types, animates pseudo-tokens, and prepares the conscience to accept fraud as fidelity.

A myth is the symbolic frame through which a code is justified and stabilized. It selects a culturally recognizable archetype or paradigm—a narrative pattern so deeply embedded in collective memory that it feels truthful, even when it supports ontological distortion. Myths do not invent meaning ex nihilo; they reassign meaning by repurposing deep symbolic patterns to legitimize codal drift.

Function: Codal framing via symbolic paradigm

Level: Archetypal / Paradigmatic

Examples:

The Hero’s Journey → autonomy leads to transcendence

The Oppression–Liberation Myth → disruption justifies redefinition

The Forbidden Knowledge Myth → moral inversion becomes heroic insight

The Apocalypse Myth → destruction becomes the necessary prelude to rebirth

In each case, the myth does not merely illustrate the code—it elevates it into symbolic inevitability. It naturalizes what should be questioned, and projects typological weight onto forms that may lack divine grounding.

If the myth frames the code, the narrative animates it. A narrative is the syntagmatic (sequential) layer—a storyline that embeds the myth within a coherent structure of time, emotion, character, and consequence. Narratives are persuasive not by logical structure but by affective immersion and repetitive patterning. They deliver the code through the heart, not merely through the intellect.

Function: Affective embedding and simulation of legitimacy

Level: Temporal / Experiential / Emotional

Example:

In a film, a disillusioned youth leaves home (call to adventure), fights a corrupt religious order (trial), and is vindicated in a climactic act of rebellion (return).

The myth is individual autonomy against religious oppression; the code is redefinition of identity apart from divine order.

Narratives make the pseudo-type feel real. They reinforce the myth with lived plausibility. The audience is not asked to believe a proposition—they are invited to inhabit a world in which that proposition is already true.

In coordinated form, this structure follows a consistent pattern:

"We will redefine this ontotype (code) using this symbolic archetype (myth), embedded within this affective storyline (narrative)."

The code supplies the attempted ontological redefinition,

The myth grants it symbolic and moral gravity,

The narrative delivers it experientially and affectively.

This triadic deployment is the semiotic delivery system of (rebellious) effigiation. It does not merely confuse meaning—it simulates legitimacy, offering a full-spectrum counterfeit of divine typological order.

This triad will be revisited and expanded in the upcoming pragmatics section, where its deployment in discourse, ritual, and media will be analyzed in detail.

When codes and tropes abandon their reflective role and become self-authorizing, they cease to serve epistemic clarity and begin to serve ontological simulation. No longer mirrors of truth, they become instruments of mimicry—designed to project moral and ontological weight onto categories God has neither defined nor authorized.

In this mode, the code no longer points to reality; it claims the power to create it. It postures as ontological fiat, appropriating the divine act of naming and being-making. The result is not merely philosophical error, but ontological insurrection cloaked in language. A closed discursive loop emerges in which meaning, morality, and identity appear organic—but are, in fact, constructed and enforced through typophoric fraud.

This is not neutral. It is a moral act of presuppositional sabotage. It hides rebellion beneath narrative, familiarity, and decorum. It rescripts creation in the image of culture, not the Creator.

Semiotics, then, is not merely interpretive—it is covenantal. To engage uncritically in the symbolic validation of pseudo-types and pseudo-tokens is not merely a linguistic or academic misstep; it is a betrayal of entrusted participatory stewardship. Humanity was never authorized to redefine kinds or simulate categories. It was called to name in reverence—not fabricate in rebellion.

The relational-ontological model confronts this directly. It insists that: only God defines ontological types (auctoritas essendi), only God may instantiate true tokens (instantiandi), and only these can bear moral, covenantal, and ontological weight. All other constructs—however coherent in logic, appealing in narrative, or forceful in affect—are counterfeit instantiations. They are not benign—they are morally animated attempts to fabricate reality without reverence. In this light, semiotics is no longer a neutral field of meaning, but a theater of covenantal confrontation. It is a battleground where every code, myth, and typophoric sign either echoes the structure of divine truth—or subverts it.

The biblical response to semiotic collapse is not merely critique, but restoration. In John 1, Christ is declared the Logos—the divine Word who not only reveals truth, but constitutes reality itself. He is the Referent, the Revealer, and the Redeemer. In Him, the disintegrated signs of fallen humanity are reconciled to their true ontological types. He is not a trope or symbol for God—He is the express image, the ontological archetype instanced in flesh.

At Pentecost (Acts 2), the confusion of Babel is temporarily circumvented: through the Spirit, the gospel is heard in every language—not by collapsing linguistic diversity, but by transcending fragmentation with unified typological truth. This is not a return to sameness, but a restoration of semantic submission to divine ontology. Each tongue recognizes the same reality in the Person of Christ.

In Christ, the integrity between type and token, sign and referent, is restored. He fulfils the Divine Double Prerogative: He is the delimited Type (Son of God) and the authorized Token (Lamb of God). He is not a typophoric gesture—He is the truth toward which all faithful typophora point.

Semiotics, seen through this theological lens, is no longer a neutral or corrupted system. It becomes a tool of covenantal clarity. When signs are rooted in ontology and shaped by relational fidelity, they once again carry the weight of truth—not merely interpretation or cultural negotiation.

Thus, the mission of theology is not to abandon semiotics, but to redeem it—to expose its fraudulent deployments and to restore its covenantal function: to bear witness to what God has spoken and instantiated. In Christ, every faithful word regains its center, and every counterfeit sign is exposed by the presence of the Real.

Historically, Christian theology has wrestled with how finite creatures can speak truthfully—though not exhaustively—about the infinite Creator. This concern centers on predication: the act of affirming something about a subject, especially across the creature-creator ontological divide: how can terms applied to God and to creatures both be meaningful?

Three classical models emerged:

Univocal Predication: A term has the same meaning when applied to both God and creation (e.g., “wise” means identically the same in both cases).

→ Rejected because it collapses the Creator–creature distinction and reduces God to a scaled-up human.

Equivocal Predication: A term has entirely different meanings when applied to God and to creation.

→ Also rejected, because it renders theological language meaningless—no real knowledge of God would be possible.

Analogical Predication: A term signifies proportionally— something can truly apply to both God and humans, but the meaning is unchanged in core reference (i.e., pointing to the same moral or ontological category); yet descaled or diminished in degree, scope, or mode of participation when applied to creatures.This allows for continuity of meaning without identity of being.

→ This became the classical model (e.g., Aquinas), and was sharpened by thinkers like Van Til, who stressed that all true knowledge is analogical: thinking God's thoughts after Him within the limits of creature-hood.

The key insight is that analogy is not poetic or merely metaphorical. It is a form of faithful typophoric predication—referring to what God has defined, not simulating what He has not. Its legitimacy rests on the divinely delimited ontological types and the covenantal relation that makes participation in knowledge possible.

Modern and postmodern semiotics collapse this reverent analogical structure. Especially in poststructuralist thought (e.g., Derrida), analogy loses ontological submission and becomes semantic improvisation.

Derrida's model of différance rejects fixed referents altogether—every sign defers to another, endlessly.

Analogy is no longer upward toward divine type, but sideways or inward, endlessly looping within culture and discourse.

All meaning is now constructed—not correspondent. Language becomes a self-referential game.

In this system, tropes cease to illuminate ontological types and become mere rhetorical tools—means of persuasion, irony, or destabilization. The result is the collapse of analogy from moral reverence to semiotic play—from witness to manipulation.

Below, we align troped with their displacement types, showing how they function either reverently or subversively. In this context, tropes function either to reveal ontological types or to displace them. Their moral weight depends on whether they return to divine reference or simulate presence.

Each trope can either function as typophoric fidelity—pointing to what God has revealed—or as typophoric distortion, simulating ontological reality while severed from covenantal authority.

In the relational-ontological model, the goal is not to abandon trope, but to discipline it—to ensure that every figure of speech is a faithful analogical witness, not a rhetorical hijack. Properly ordered, analogy becomes a pathway to worship. Misused, it becomes a mechanism of effigiation. These figures of speech are not neutral—they can either illuminate truth analogically, or simulate legitimacy rhetorically.

The biblical use of analogy is never autonomous. It is reverent, ontologically anchored, and morally obligated to return to the type it gestures toward. This is what we identify as onto-typophoric reference: the analogical use of language that maintains covenantal fidelity by always pointing back to a divinely defined ontological type.

“The Lord is my shepherd” → clarifies divine care and guidance, yet does not collapse God into creature.“God is a rock” → evokes permanence and stability, but preserves God’s transcendence and personal being.

In both cases, the analogy is faithful because it remains typophoric—it gestures, not replaces. It leads the mind upward without claiming equivalence. The trope functions analogically, not ontogenetically.

This distinction matters because analogy may erode a sign’s integrity without ever touching the ontotype’s fixity. Fixity is the external, God-secured boundary of the kind, impervious to cultural reassignment; integrity is our moral and axiological coherence in speaking that kind. When tropes drift without returning to their referent, integrity collapses, but the type’s fixity remains unshaken—waiting for language to repent and realign.

By contrast, secular usage increasingly employs tropes without return. These gestures do not point to real types—they simulate moral weight, projecting a sense of authority onto ideas God has not sanctioned. They do not elevate thought—they collapse category.

“Love is love” → a tautology presented as moral insight, collapsing all forms of love into a single undifferentiated category, eliminating the ontological distinctions between covenantal, sexual, filial, and divine forms.

“Identity is fluid” → a metaphor repurposed as ontological assertion, shifting a figure of speech into a claim of kindhood, effectively attempting to instantiate a pseudo-type.

These are not mere rhetorical devices. They are fraudulent typophoric acts—signs that claim the aura of truth without the authority of divine instantiation. In the relational-ontological model, discernment requires analogical return. Every analogy must be judged by one question: Does this sign return to a type that God has defined?

If it does, it is faithful analogy.If it does not, it is effigiated simulation—a rhetorical counterfeit, mimicking truth while severed from covenant. This is not a matter of stylistic precision but of moral allegiance. To speak truly is to submit the sign to being, and to submit being to God.

In a relational-ontological framework, semiotics is not a neutral field of sign production. It is a morally accountable domain—one that either reflects the fixed ontological kinds established by the One True God or simulates authority through counterfeit codes. The semiotic act, therefore, must be judged not merely by internal coherence or cultural usage, but by its fidelity to divinely revealed ontotypes. The sevenfold ontological criteria provide a diagnostic structure by which the semiotic field can be tested for truthfulness or exposed for effigiation.

Fixity: Do signs anchor meaning to real, God-delimited types? Or do they allow fluidity that permits category drift? When semiotic tokens are detached from their fixed referents, they no longer signify—they simulate.

Integrity: Is there internal coherence between the signifier and the kind it claims to signify? Manipulated signs fracture this coherence by disjoining appearance from being—this is typophoric fraud.

Parsimony: Are signs multiplied only where necessary? Or is meaning inflated through over-signification and symbolic redundancy? Semiotic parsimony resists the saturation of discourse with needless layers of interpretive simulation.

Typological Convergence: Do codes align with all other divine kinds (truth, mercy, justice)? Semiotic acts must not contradict the wider moral structure of God’s reality. Misaligned codes distort perception and habituate epistemic disorder.

Modal Implication: Does a code suggest what is possible or permitted in God’s world? Or does it extend meaning into modalities that God has not authorized? Fraudulent signs often function as moral permissions in disguise.

Telic Vector: Does the sign orient the soul toward redemptive alignment with God? Or does it serve expressive autonomy, institutional agendas, or social engineering? Every sign has an aim—faithful semiotics points to the Creator.

Divine Assignment: Has God assigned this code, category, or referent as legitimate? Or is it human-generated? Semiotics becomes effigiated when the sign attempts to confer being rather than recognize it.

In short, semiotics is not just about what signs mean, but whether signs are authorized to mean at all. The sevenfold ontotype criteria expose when signs serve as covenantal mirrors—or as discursive forgeries. By submitting every code and referent to this diagnostic lens, we reclaim the semiotic field as a site of moral discernment and covenantal alignment.

To manipulate signs is to manipulate reality. This is not merely rhetorical—it is a moral and ontological betrayal. In the biblical worldview, signs are never ethically neutral. Every word, image, role, and referent either aligns with God’s ontological design or simulates an alternative. In a fallen world, the engineering of pseudo-types, the deployment of fraudulent typophoric gestures, and the projection of effigiated tokens becomes a systematized form of semantic rebellion.

Semiotics, then, is not about interpretation alone—it is about allegiance.The question is not just what does this mean, but who has the right to define meaning, and toward what end?

The biblical framework holds that signs were created to correspond with being, not to conceal or simulate it. Codes were meant to reflect covenantal categories. Tropes were meant to reveal deeper truths through reverent analogy. But when cultural codes invert moral order, and tropes are weaponized to mock or obscure the sacred, then the manipulation of meaning becomes a morally culpable act—not just against language, but against the Creator who defines reality.

The misuse of signs is not a stylistic deviation.It is a pseudo-instantiative act—a claim to ontological authority where there is none.

In this light, the mission of Christ is not merely to forgive sinners or to teach truths—it is to restore authentic signs: truth, mercy, justice, identity. His life and work reestablish the alignment between type and token, between being and word. Christ is the true referent and the true revealer—and in Him, semiotic repentance and ontological realignment converge.

The call, then, is not just to speak rightly, but to mean faithfully. To signify only what God has defined. And to refuse all counterfeits—no matter how plausible, poetic, or persuasive.

The integrity of signs depends not only on their ontological anchoring, but on how they are used—intentionally or deceptively—in discourse. Having clarified what signs are, we now turn to how they function: in context, in power, and in conflict. For those seeking precision at the level of foundational meaning-units, the Multidimensional Morpheme Analysis Tool (MMAT) —provided in the Appendix—offers a method of semantic discernment that precedes and supports all higher-order sign manipulation. With this foundation in place, we now enter the field of Pragmatics .

The dynamics traced here in Semiotics—codes, tropes, typophora, and effigiation—intersect with deeper cognitive and diagnostic mechanisms treated elsewhere in this framework. For further exploration:

See the Principle of Nominal Assembly for how naming crystallizes tacit content into operable symbolic units.

See the Naming vs Ambiguity essay for how ambiguity is collapsed and counterfeit assemblies exposed.

See the Onto-Discursive Analysis (ODA) tool for how these principles function diagnostically within discourse.

Together these strands form the foundation of Claritics , the discipline of ontological disambiguation, which integrates naming, assembly, and disambiguation into a unified practice of defending truth against manipulation.

Footnotes

*

Theodicy, classically understood as the justification of God's goodness in the face of evil, can also be seen in relational terms: not merely as a defense of God before man, but as God allowing His justice to be morally scrutinized. Throughout redemptive history, God opens His judgment processes to examination—both by the righteous and the condemned (Gen. 18:25; Rom. 3:4; Rev. 20:12). This transparency does not compromise divine sovereignty but reinforces it, showing that God’s verdicts are not arbitrary but morally intelligible. Even those who reject Him are shown to be self-condemned, not deceived victims of hidden decrees. See

Appendix C

for a more detailed discussion.

Note on terminology:

`It is an irony not lost on us that semiotics, a discipline ostensibly devoted to clarifying how meaning is conveyed, has produced some of the foggiest and most ambiguated taxonomies of its own. The same basic triad reappears under different labels: Ferdinand de Saussure’s signifier/signified dyad (leaving the referent implicit), Charles Sanders Peirce’s representamen/object/interpretant triad, and Ogden & Richards’ symbol/thought/referent triangle. Yet each tradition clouds rather than clarifies by collapsing categories or neglecting ontology altogether. In the Submetaphysics framework, we therefore propose the simpler and clearer rendering of sign (external marker), referent (external reality), and signification (internal interpretation). This does not alter the main thrust of our argument, but it underscores how the very discipline charged with disambiguation has often multiplied confusion.

Summary

This section showed how the semiotic landscape of secular modernity has become a theatre of counterfeit ontology—where pseudo-types are fabricated, pseudo-tokens are imposed, and signs are severed from the ontological truth they once mirrored. Tropes that once functioned as reverent analogies now serve as tools of ontological subversion. Codes, instead of reflecting divine categories, simulate being and manipulate morality. This systemic discursive rebellion is not neutral; it is a form of theological insurrection that arrogates the divine prerogative to define and manifest being. Yet, the biblical model does not abandon semiotics—it redeems it. Through the Logos, who is both the Word and the referent, God restores the integrity of language, re-establishing the covenantal bond between sign and meaning. In this light, semiotics becomes a site of moral allegiance: to speak truthfully is to submit linguistically to ontological reality, and to resist the simulation is to participate in redemptive fidelity.