All human thought begins with some account of being—of what is real, what kinds of things exist, and how they come to be. But modern ontological frameworks—whether scientific, philosophical, or symbolic—often sever being from divine origin and moral structure. They treat existence as autonomous and categories as emergent or socially constructed.

This Ontology section is therefore presented in two coordinated parts. Part I diagnoses the fragmentation and collapse of secular ontological models—philosophical, scientific, and linguistic—that attempt to define being apart from the authority of God. It exposes the failure of self-referential systems to ground truth, meaning, or moral coherence. Part II builds upon this critique, tracing how such ontological failures persist through patterns of evasion, substitution, and simulated presence. Rather than being neutral errors, these patterns reveal a moral posture: the suppression of real kinds and the rejection of divine referentiality. Part II culminates in a biblically grounded diagnostic: the seven-fold criteria for discerning true ontological types (see §2b).

Together, these two parts lay the foundation for a relational ontology—the revealed alternative in which being is not abstract essence but covenantal participation. All kinds are divinely delimited; all instantiation proceeds from God’s speech; all order is moral and filial. The apex of this ontology is not merely creation, but regeneration—where moral agents are restored to true being by alignment with the Father through the Son. Across both parts, this framework affirms that human beings are not ontological originators but derivative participants. Reality is not ours to construct, but to receive and inhabit through reverent submission.

Modern discourse often assumes that epistemology, ontology, and language are interdependent—that the tension between belief, being, and expression can somehow resolve itself dialectically. But this assumption fails both logically and morally.

Ontology must precede epistemology. The stability of referents is a precondition for any coherent claim about truth or meaning. Without ontological grounding, epistemology floats without anchor, and semiotics becomes a self-referential game.

In secular models, this instability results in a vicious loop: either language constructs reality (constructivism), reality erases meaning (materialism), or reality lies beyond meaning (Platonism). But all three collapse when asked to produce referential stability and moral accountability.

In the biblical model, God breaks the loop: He gives both the world and the Word. Truth is not constructed or emergent, but disclosed—revealed by the One who both creates being and grants meaning.

Modern ontological frameworks—far from neutral or coherent—have fractured into mutually incompatible and often self-defeating systems. Three dominant trajectories illustrate this fragmentation: Platonic abstraction, materialist naturalism, and postmodern constructivism.

Platonic metaphysics posits that the true essence of being lies in immaterial Forms—perfect, changeless, and eternal. In this view, the material world is a mere shadow or imperfect manifestation of these higher realities. Though influential in Western philosophical history, this abstraction has two critical consequences: it divorces meaning from material existence, and it elevates abstract universals over manifest particulars, rendering actual, embodied entities as ontologically secondary.

The early dialogues of Plato—such as Timaeus and Phaedo—and later Neoplatonists like Plotinus illustrate this dualistic outlook. In modern times, essentialist echoes of this thought persist wherever identity is conceived as fixed apart from embodied or relational context.

Yet by treating every genuine predicate (one that truly signifies a universal property) as demanding its own independent Form, the Platonic scheme commits to ontic multiplication—violating ontological parsimony by proliferating irreducible kinds far beyond explanatory necessity.

Materialism, in contrast, denies the existence of any transcendent reality altogether. For thinkers like Bertrand Russell (A Free Man's Worship), Richard Dawkins, and Daniel Dennett, the universe is a vast, impersonal mechanism—unguided, unpurposed, and amoral and functionally fatalistic. In this ontology, being is accidental, and value is illusory. There is no "good" inherent in creation—only what can be explained by evolutionary function or neurological impulse. Morality becomes a sociobiological adaptation; personhood and agency collapses into an inert by-product of brain chemistry. The result is ontological flattening: all things are reduced to matter in motion, and meaning is no longer given but constructed.

Postmodern ontology represents not so much a rejection of metaphysics as its dissolution. With roots in Nietzsche's perspectivism and Heidegger's questioning of Being, and more explicitly in the works of Michel Foucault, Jean-François Lyotard, and Judith Butler, postmodern thought treats being as culturally or linguistically constructed. Categories are contingent. Truth is narrative. Identity is performance. As Lyotard famously put it, the postmodern condition is defined by "incredulity toward metanarratives." In this framework, being becomes unstable and contested. The result is not just skepticism, but ontological volatility: nothing can be finally known, defined, or trusted.

The three dominant ontological trajectories outlined above—Platonic abstraction, materialist naturalism, and postmodern constructivism—differ dramatically in content and method. Yet they converge in one crucial respect: each ultimately constructs its metaphysical vision from within a closed system. In doing so, they commit not a subtle oversight but a fatal methodological fallacy—affirming the consequent. They infer the truth of their ontological assumptions from the very effects their system predicts. Whether through the ideal reflection of Forms, the lawful regularity of matter, or the variability of cultural codes, each treats effect as cause, coherence as foundation, and thus collapses into circular reasoning.

That is, they rely on internal mechanisms—whether rational categories, empirical observation, or cultural constructs—to both generate and justify their ontological claims. In the process, meaning, being, and value are no longer received but fabricated, negotiated, or reverse-engineered from within the system itself. In short, they simulate ontology rather than disclose it.

This dynamic is most clearly seen in the growing entanglement of semiotics and philosophy, particularly in postmodern and technocratic systems. Semiotic structures (codes, symbols, narratives) and philosophical categories (identity, truth, substance) begin to mutually reinforce each other. Semiotics provides the linguistic scaffolding, while philosophy supplies the conceptual architecture. Together, they create a self-referential loop—a system that generates the appearance of grounded-ness without appealing to anything beyond itself. A key mechanism within the self-referential semiotic-philosophical loop is analogy. Analogy enables the extension of meaning from one domain to another—often by resemblance, metaphor, or perceived functional similarity. (To be discussed comprehensively under Semiotics). Analogy, in a subordinate and reverent role, it can serve epistemic clarity. But when analogy becomes the primary means of ontological construction, untethered from any revealed or created ground, it ceases to illuminate and begins to fabricate. An ontological type cannot be constructed by analogy, resemblance, or perceived function. Only divine designation can determine which kinds of beings may exist. Without this grounding, even coherent or emotionally compelling categories remain metaphysically null.

Misapplied analogy can encourage the generation of pseudo-tokens and the redefinition of types—signifiers that resemble legitimate ontic expressions but lack correspondence to any divinely defined type. As these signifiers are repeated, institutionalized, and emotionally reinforced, they accumulate into what may be called pseudo-ontics and pseudo-types: conceptual artifacts that behave like true ontological categories but are, in essence, simulated kinds. They carry the appearance of metaphysical weight, yet are constructed entirely within the closed loop of secular codes and philosophical abstraction.

A category may be conceptually legitimate, yet ontologically false if it lacks divine sanction. Coherence before the mind does not equate to legitimacy before God. Such pseudo-types—though often linguistically coherent or socially functional—are unauthorized by the Absolute and must be sharply distinguished from real, God-ordained types. They are not innocent semantic innovations; they are ontological impostors, born not of creation but of conceptual autonomy.

This is the heart of the crisis of secular ontology. It is not merely that being is misunderstood or misdescribed; it is that the very structures used to describe it have become self-justifying and untethered from reality. Secular ontology does not simply posit a wrong view of the world—it builds a world that is epistemologically closed and ontologically hollow. The result is an inflation of categories (identity, agency, meaning) with no external referent—no tethered “absolute”—leading to confusion, volatility, and ultimately, collapse.

This critique is not merely abstract. It helps explain why modern secular systems can sustain moral discourse, identity politics, and scientific explanation without reference to an Absolute, while simultaneously disintegrating under the weight of their own internal contradictions. They function as hermetic systems, borrowing enough from the remnants of biblical ontology to appear coherent, but rejecting the Source that alone can sustain them.

The biblical alternative cuts decisively through this loop. It grounds ontology not in analogy or convention, but in divine speech and moral disclosure. It refuses the simulation of being and insists on a world that is both given and good.

Taken together, these trajectories—idealism without contact, materialism without value, and constructivism without foundation—lead to a shared outcome: the loss of meaning, purpose, and moral orientation. Existence becomes either too distant to matter, too flat to inspire, or too fragmented to hold together. This is the crisis relational ontology addresses.

Modern ontological frameworks do not merely lack coherence—they lack hierarchy. The foundational error is ontological inversion: treating knowledge, language, or signification as primary, and being as derivative or constructed. In reality, truth is not first an epistemological condition—it is an ontological category, grounded in the being of the One who is.

If reality is composed of kinds—both tangible and intangible—then truth, like number, causality, and relation, must be classified among the intangible ontological kinds. It is not reducible to syntax, function, or perception. One cannot coherently affirm a structured reality while denying the reality of truth. To know anything at all is to presuppose that truth exists. To deny it is not merely error—it is a collapse into ontological fraud. It is to destroy the foundation of knowing itself.

When Jesus declares, “I am the way, the truth, and the life” (John 14:6), He locates truth not in reason, perception, or coherence, but in Himself—as the ontological foundation, the Alpha and the Omega (Revelation 22:13), from whom and to whom all meaning flows (cf. Romans 11:36). This is not merely a claim of epistemic authority, but a declaration of divine being. Truth, in its highest sense, is not discovered—it is disclosed. It does not emerge from human systems; it confronts them. It is not produced by cognition; it is received through revelation.

This suppression is not merely moral (though it is that, cf. Romans 1:18)—it is also logically fallacious and intellectually dishonest:

It commits a category error by reducing truth to social construct or linguistic utility.

It falls into performative contradiction by asserting “truth is not real” while relying on truth to make that assertion.

It exhibits special pleading—applying logic, judgment, and structure in every other domain, but denying them where truth demands moral submission.

What results is not simply philosophical confusion, but an entire simulated intellectual ecosystem, constructed atop suppressed acknowledgment. Modern systems continue to act as though truth is real—publishing, critiquing, systematizing—while denying its ontological grounding.

This is why the truth of truth is rarely foregrounded: epistemic pluralism avoids ontological hierarchy; interpretive traditions defer to user autonomy and avoid confrontation; academic systems fear that admitting truth as a kind would ultimately require theological submission—not to an abstract order, but to a personal, moral, self-revealing God. Even many theological models fail at this point—preferring propositional clarity or systematic theology over truth instantiated in the person of Christ.

From this, a necessarily ordered submetaphysical cascade is recovered:

Ontology → Epistemology → Semiotics→ Pragmatics

This ordering is not an innovation—it is a rediscovery. It is not speculative—it is structurally necessary. It is the only order in which meaning remains coherent, truth retains referential integrity, and speech retains moral accountability. To collapse or reverse this sequence is to:– sever knowing from being—sever meaning from reality— and sever the creature from the Revealer.

Many have gestured toward aspects of this order—Plato through forms, Aristotle through essences, Aquinas through teleology (further explored in detail in Appendix D0 )—but none grounded it in the relational being of the One True God as revealed in Christ. This framework does not claim novelty, but clarity: it names what has long been obscured by philosophical synthesis, theological systematization, or epistemic autonomy.

As the following subsection will show, this inversion lies at the heart of modern collapse. What remains is not merely intellectual error, but a structural rebellion against the order of being itself.

This onto-epistemic disconnect lies at the root of secular metaphysics, modern theology, and postmodern semiotics alike. This is not merely a philosophical error— but an ontological-epistemological rupture that defines the modern intellectual condition. Rather than knowledge flowing from being, being is now treated as inferred from knowledge—or worse, constructed by it. Truth is no longer received as ontological disclosure, but fabricated within epistemic systems.

The result is not just confusion—but simulation. Systems arise that imitate the grammar of truth while severed from its source. Knowledge appears functional, even elegant, but it no longer corresponds to what is. Meaning persists, but without mandate. This framework reasserts the necessary alignment: ontology must precede epistemology, not merely logically, but covenantally—because truth is not just what we learn; it is who we face.

The first onto-epistemic rupture did not begin in philosophy, but in pre-lapsarian Eden. When the serpent whispered, “Ye shall be as gods, knowing good and evil” (Gen. 3:5), the temptation was not merely intellectual—it was epistemological. It invited the creature to know apart from receiving, to determine what is good and evil by internal judgment rather than divine definition. This was not a neutral pursuit of knowledge, but a rejection of relational dependence—an attempt to collapse the Creator–creature distinction under the guise of enlightenment. “Yea, hath God said…?” (Gen. 3:1) did not merely introduce doubt—it shifted the posture of knowing. Truth, once received as revelation, was now subject to autonomous evaluation.

This was the first fracture: epistemology became autonomous, detached from worship and relation. Adam and Eve did not begin by redefining being—they began by reauthoring how being is known. Epistemology was exalted over ontology, and relation was quietly severed. As Paul would later diagnose: “Professing themselves to be wise, they became fools” (Rom. 1:22). The crisis was not ignorance, but epistemic autonomy—not a lack of access to truth, but a refusal to receive it.

This epistemic breach immediately yielded a relational breach: “And Adam… hid themselves from the presence of the LORD God…” (Gen. 3:8). The voice that once defined all things was now feared and avoided. Fellowship collapsed—not simply due to behavioral infraction, but because the relational architecture of moral order had been overturned. To reject God’s voice as source is to forfeit the relation that sustains ontology.

Only then came ontological inversion—not as an explicit aim, but as the natural effect of a severed relation and autonomous knowing. What God had clearly marked as the boundary of death was now reinterpreted as a source of life and wisdom (Gen. 3:6). “And when the woman saw that the tree was good for food… and a tree to be desired to make one wise…” she declared reality not by reference to God’s word, but through sight, appetite, and desire. But this appetite was not merely physical—it was ontological. She desired selfhood: to become as God, to possess wisdom without submission. Ontology became plastic—no longer grounded in divine delimitation, but measured by self-perception.

This is inversion: when kind is no longer received but authored. What began as a desire to enjoy God’s creation on one’s own terms hardened into a redefinition of reality itself. The initial dislocation was not an overt metaphysical sabotage, but a shift from submission to assertion. Yet once truth is severed from relation, being must be redefined to match the new center of meaning—the self.

Over time, what began as a bid for independent participation in creation came increasingly under the influence of the original instigating oppositional intelligence—an agent not merely of disorder, but of counterfeit order. Jesus identifies this adversary as “a liar, and the father of it” (John 8:44)—not merely a corrupter of facts, but a deformer of kind, whose aim is to erase the image of God wherever it is reflected (cf. Rom. 1:23–25). This ambition—to ascend, to redefine, to displace the divine order—is prefigured in the fivefold boast of Isaiah 14:13–14: “I will ascend…I will exalt…I will sit…I will ascend…I will be like the most High.” Though addressed to the king of Babylon, the pattern reveals the archetype: a will to redefine kind, to collapse the Creator–creature distinction under the guise of exaltation. What began as a subtle shift toward epistemic autonomy hardened into a deliberate project of ontological usurpation—not merely to enjoy creation on one’s own terms, but to re-author creation in one’s own image.

In a single act, the moral, epistemological, and ontological orders collapsed—not from ignorance, but from the presumption of autonomy. Put plainly: we will determine how we know; we will deny the relationship, and we will define the kind. This is the triadic inversion—the structural collapse of truth, revelation, and being.

From that moment, human cognition became misaligned. Truth, once relational and disclosed, was now grasped, judged, and eventually simulated. The result was not mere error, but the collapse of onto-epistemic bandwidth: the loss of ontological clarity, the rise of interpretive autonomy, and the proliferation of systems unanchored from the Source. True epistemic bandwidth is not about informational range, but about ontological ascent—whether thought is drawn toward or away from the apex of disclosed being. It is not recursive or self-referential, but teleological: oriented toward the Source who defines both meaning and moral obligation. This structure is explored in the Conical Cognitive Model (Appendix D).

7. Structural Repentance: Reversing the Onto-Epistemic Cascade

After the breach, truth became objectified—detached from God's voice and measured by human faculties. Epistemology no longer flowed from ontology, but operated in isolation, reconstituted as intellect, intuition, or culture. In that moment, the creature fell not merely from grace, but from right ontology.

This framework offers not a philosophical correction, but a call to structural repentance. The cascade must be reversed: submission before definition → being (kinds) before belief → truth before interpretation.

The fall was not just disobedience. It was the disintegration of created order at every level: relation, ontology, and knowledge. Adam and Eve didn’t just eat fruit—they repositioned themselves as epistemic arbiters and ontological definers, and in doing so, dislodged their own being. The only path to restoration is to reverse the collapse—through ontological submission, relational realignment, and epistemic humility.

True ontology is both generative and restrained. Scripture discloses only three irreducible orders of being—the (self-existent) Absolute, (created) persons, and created kinds—and assigns each a determinate “vibrational bandwidth” within which it may instantiate. Nothing further is needed; anything more is conceptual surplus or pseudo‑type. In this sense the relational-biblical model obeys a principled parsimony: it refuses to “multiply entities beyond necessity,” yet also refuses materialist reduction or postmodern flattening. By rooting every legitimate category in divine designation, it achieves the rare balance of metaphysical economy and existential richness. Secular systems, by contrast, either proliferate abstractions (Platonic ideals), collapse distinctions (materialism), or fragment endlessly (constructivism)—each a violation of ontological modesty. Thus, parsimony is not mere tidiness; it is a moral alignment with the Creator’s own disciplined creativity.

In classical and analytic philosophy, ontology addresses the foundational question: What exists, and what kinds of things exist? Across historical systems, several basic distinctions have consistently shaped the ontological landscape.

Universals and Particulars: This distinction, classically treated by Plato and Aristotle, and later refined by Boethius, Aquinas, and in contemporary terms by David Armstrong, refers to whether a kind or property (e.g., “justice,” “redness”) can be instantiated in many individuals (abstract universals), or whether it exists as a unique, singular entity (manifest particulars).

Substance and Accident: Most explicitly developed by Aristotle in his Categories and Metaphysics, this distinction holds that substances exist in themselves (e.g., a human being), whereas accidents (e.g., color, shape, mood) inhere in substances but do not subsist independently.

Essence and Existence: Further elaborated in the medieval synthesis by Aquinas, this distinction frames essenceas what a thing is (its definitional nature), and existence as that it is (its ontological actuality). For most created beings, essence and existence are distinct and must be united by an act of being. (The essence–existence distinction echoes the abstract–concrete tension seen in universals and particulars, but it adds a vertical ontological dependency structure—highlighting that things do not simply instantiate forms; they are granted being by God who alone possesses existence as essence.)

Type and Token: In modern logic and semiotics, following figures such as Charles Sanders Peirce, Gottlob Frege, and later Willard Van Orman Quine, this distinction is used to describe symbols: a type is the abstract or general category (e.g., the word “dog”), and a token is a particular instance of that word in use (e.g., one printed occurrence of “dog” on this page). In this framework, however, ‘type’ is a divinely delimited ontological kind, while each ‘token’ is an anthropic exemplification within that limit; by contrast, ‘substance’ and ‘accident’ remain second-order philosophical abstractions about those exemplifications.

These models have provided enduring tools for reasoning about kinds, properties, and identity. However, in most philosophical traditions—particularly those outside theistic metaphysics—instantiation is treated as either a logical function (in the case of universals) or a linguistic one (in the case of tokens). The question of who instantiates, and on what ontological grounds, is often left unaddressed.

In contrast, the framework developed here builds upon these distinctions but advances a more theologically grounded model. It begins with the conviction that all types are either divinely defined or fictively constructed, and that true instantiation belongs to God alone. Whether one is speaking of a substantial being (such as a lion) or a moral act (such as mercy), its real presence in the world is not merely a recurrence of a pattern, but an ontologically charged event—an act of divine permission or alignment.

We therefore distinguish:

Ontological Types – Real kinds embedded in the order of creation by divine prerogative.

Ontic Instantiations – Realized presences of those kinds in the world, either through essentiation (beings) or exempliation (acts).

This revised model extends classical metaphysics by rooting it in relational theism: being is not neutral, but accountable. What follows is a formal exposition of these two modes of instantiation.

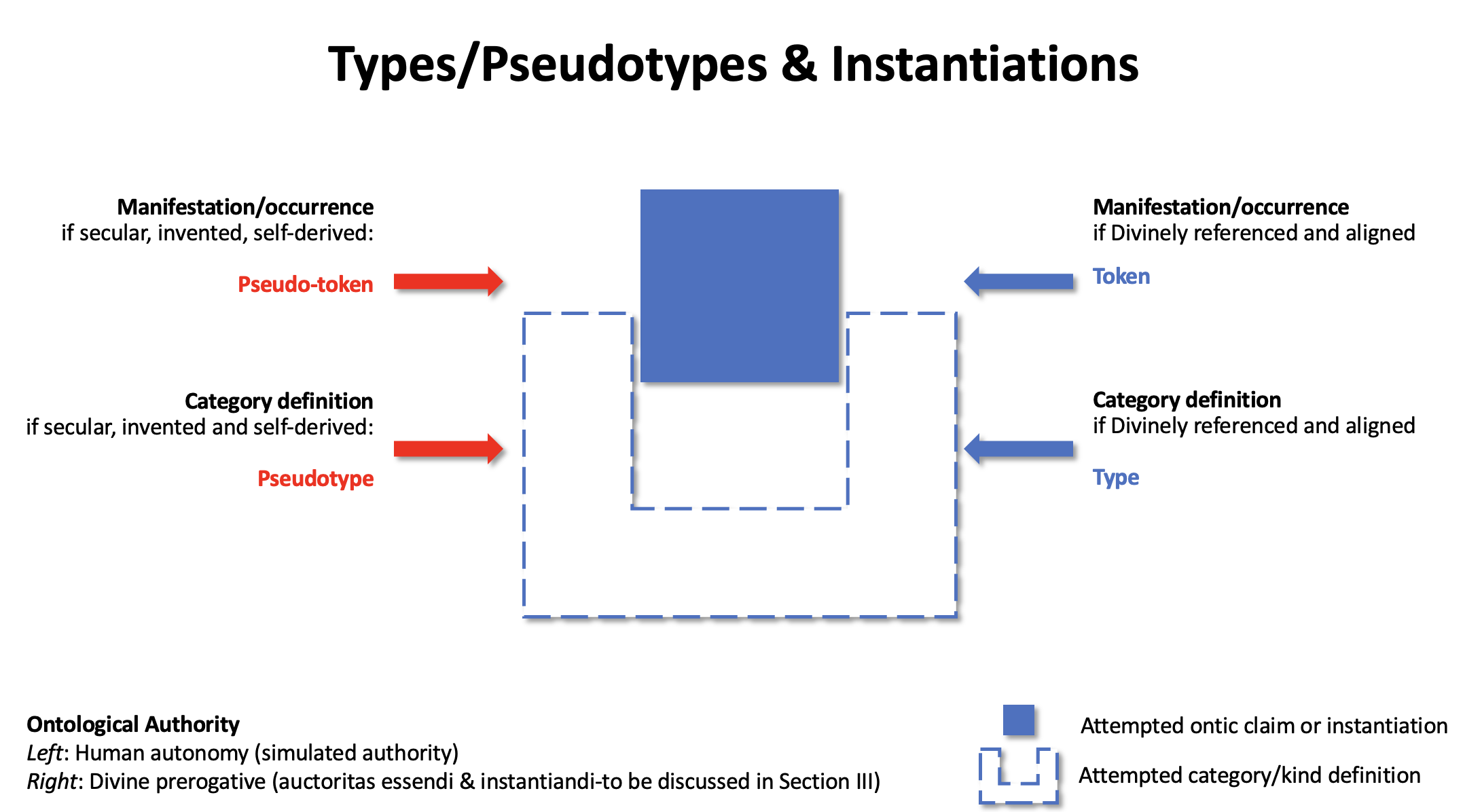

In classical semiotics and logic, a token refers to a particular instance of a general type—for example, the word “justice” appearing three times on a page constitutes three tokens (instances) of one type. In this framework, we conscript that terminology analogically to expose a deeper ontological danger: the simulation of being without the right to be.

In our model, a pseudo-type refers to a conceptual ontological category that mimics a God-given kind but lacks His ontological legitimacy—such as a socially constructed identity or a redefined moral role with no divine prototype. A pseudo-token is a signifier that attempts ontic instantiation—either discursively or performatively—by claiming the identity or function of a real type without divine warrant. While it may be linguistically proposed or even manifestly embodied, its ontological claim is fraudulent. It simulates the presence of a God-defined kind but arises from conceptual or moral autonomy, not creation.

Where secular frameworks sever signification from ontological grounding, they not only proliferate manufactured false categories (pseudo-types), but also encourage the arrogation of their proposed corresponding pseudo-tokens—symbolic projections masquerading as ontic realities.

Such pseudo-instantiation presumes an authority that belongs to God alone—the right to define kinds and to call them into being. This prerogative will be formalized in Section III as the foundation of all ontological legitimacy.

Visualizing Illegitimate vs. Legitimate Ontic Claims

(A Semiotic Contrast Rooted in Ontological Authority)

This diagram visualizes the relational-ontological distinction between true and false instantiation. Pseudo-types are unauthorized categories; pseudo-tokens are their projected, performative manifestations. All legitimate ontic instantiation flows from divine prerogative.

Pseudo-tokens, linguistic or performative claims to reality without ontological-type backing, typically arise within self-referential systems—sociopolitical, philosophical, or psychological frameworks that presume the authority to declare what counts as real. These systems simulate ontic reality through repetition, emotional reinforcement, institutional recognition, or linguistic affirmation. But none of these legitimizes actual being.

This simulated instantiation is often masked by moral rhetoric or appeals to justice, inclusion, or liberation. Yet such appeals—however compelling—do not create new kinds of being. They may alter social perception, but not ontological status. Without divine legitimacy, they remain suspended in a semantic no-man’s-land: conceptually plausible, even emotionally persuasive, but metaphysically illegitimate.

To expose pseudo-tokens is not to deny human dignity or the complexity of lived experience. Rather, it is to insist that not all speech acts or manifest gestures confer being or legitimacy. Some simulate; some deceive. Whether through language or action, a claim to reality remains ontologically null if it lacks divine warrant. The performative power of speech and the visibility of enacted roles do not override the Creator’s exclusive right to define, distinguish, and instantiate.

Indeed, the act of naming itself is covenantal and delegated. Adam was given authority to name the animals (Genesis 2:19), but only within the boundaries of God's created kinds (discussed further in Semiotics). He did not create; he discerned and articulated. This is the ethical model for all ontology: speech must respond to revelation, not generate reality. The crisis of modern ontology lies precisely here—in the arrogant reversal of that order.

Thus, pseudo-tokens represent the culmination of ontological rebellion. They are not simply false ideas; they are counterfeit presences. They perform as if being were self-authorizing—as if a thing could exist because it is asserted, felt, or institutionalized. They collapse the relational cascade (Ontology → Epistemology → Semiotics) into a closed loop of assertion and recognition, bypassing truth altogether.

In this light, pseudo-tokens must be named for what they are: linguistic or performative deceptions. Their danger lies not in their visibility, but in their plausibility. They traffic in the semantics of legitimacy while hollowing out the metaphysics beneath.

Their proliferation constitutes a moral and epistemic crisis because it trains the moral agent to accept simulation as substance. It erodes the human capacity to discern what is, replacing ontological reverence with expressive autonomy. Ultimately, it invites persons to play God—by presuming the power to name into being.

Their proliferation constitutes a moral and epistemic crisis because it trains the moral agent to accept simulation as substance. It erodes the human capacity to discern what is, replacing ontological reverence with expressive autonomy. Ultimately, it invites persons to play God by presuming the power to name or to enact into being—forgetting that naming does not create being; it must answer to it.

Having disestablished secular and speculative models of ontology, what follows is a constructive theological recovery of biblical ontology—grounded in divine prerogative and ontological clarity. This foundational section clarifies what is meant by ontological types, instantiation, and relational categories throughout the remainder of the framework.

Readers who wish to understand this framework’s position on the identity, origin, and relational ordering of the Father and the Son are invited to consult Appendix A . There, the terms substantiveontohomogeneity and distinct ontorelationality are introduced to articulate the Son’s true divinity and true relation—without reliance on peri- and post-Nicene metaphysical categories.From this point forward, for the sake of simplification, references to “God,” “the Creator,” or “the One” will refer to the Father, unless otherwise specified. This is not a denial of the Son’s divinity, but a clarification of divine prerogative as rooted in the Father’s ontological sourcehood, consistent with Christ’s own testimony (John 5:26; 16:28).

We use “God” to mean the Father as the originator and holder of the ultimate prerogative, even though the execution may have taken place through the ontologically distinct and real only begotten Son.

The biblical doctrine of ontology begins not with abstraction but with proclamation: "In the beginning God created..." (Genesis 1:1). Grounded in divine speech, Scripture practices a disciplined ontological parsimony—a theme we formalized above. The repeated affirmation throughout the creation account—"And God saw that it was good" (Genesis 1:4, 10, 12, 18, 21, 25, and 1:31) revealing God’s own moral and ontological verdict—an evaluation that is final, binding, and good. This establishes a foundational principle: ontology in Scripture is not merely about the fact of existence but value-infused existence. Creation is not accidental or morally neutral; it is good, ordered, and intentional. This goodness is not utilitarian or pragmatic but reflects the moral character of the Creator Himself. It conveys not only what things are, but what they are for, and how they ought to be treated. Thus, biblical ontology is ethically charged from the outset. The moral valuation—"good"—imparts modal force: it obliges human response in the form of reverence, stewardship, and alignment with the Creator's design.

This theological ontology is further deepened in the New Testament. John 1:3 declares that "All things were made by Him; and without Him was not any thing made that was made." This is not merely a metaphysical statement but an ontological exclusivity clause. All being flows through Christ, the Logos. Anything that claims existence independently of Him is not simply extraneous—it is false, deceptive, or simulacral. Here, the Logos functions as the bridge between ontology and epistemology: Christ is not only the means by which things exist, but also the medium through which they are known and understood. Creation is thus not only real but rationally accessible because it is ordered through divine speech.

Colossians 1:16–17 intensifies this vision by stating that all things were created through and for Christ, and that in Him all things hold together. The ontology of Scripture is not static or self-sustaining. Being is not only created but also continuously upheld—personally and sovereignly, by the Son. This implies that existence is contingent, not autonomous—not simply caused once, but ongoingly sustained. The very coherence and intelligibility of reality depend on Christ’s active upholding (Col. 1:17; Heb. 1:3). Ontology, in the biblical frame, is thus both historical and dynamic: it begins in the creative act and is preserved by the sustaining will of the Son, even for those in rebellion. While relational restoration is the condition for the fullness of being (John 17:3), ontic continuity itself is preserved during probation—not by merit, but by divine forbearance and covenantal patience (Rom. 2:4; 2 Pet. 3:9; Luk 13:6-9; Ecc 8:11), to allow for moral confrontation: precipitating volitional repentance, or rejection.

Other scriptural texts reinforce and elaborate this picture. Romans 1:20 affirms that creation is inherently revelatory: "His invisible attributes... have been clearly perceived, ever since the creation of the world, in the things that have been made." Ontology is not opaque—it is communicative, disclosing divine reality. Hebrews 11:3 teaches that "the worlds were framed by the word of God, so that what is seen was not made out of things that are visible"—a clear indication that ontology is word-based and intentional, not arbitrary or emergent from chaos. Psalm 33:6,9 declares: "By the word of the LORD were the heavens made... For He spoke, and it came to be; He commanded, and it stood firm." Language and ontology are fused in the biblical account: God speaks, and being follows. The world is not only created but also linguistically constituted—formed through speech, meaning, and divine intention.

Taken together, these texts establish that biblical ontology is fixed, meaningful, and morally weighted. God’s declaration of "good" is not a casual appraisal but an ontological judgment with ethical and modal consequences. It signals that there are fixed types in creation—determinate categories that define what things are and are meant to be. The instantiation of these types in the form of actual beings (semiotic tokens or ontic instantiations) is likewise predetermined, not subject to endless redefinition. These fixed types, revealed and sustained by God, stand in contrast to pseudo-ontological categories that may be conceptually plausible or socially reinforced, but have no basis in God’s created order. Their existence is permitted only in the imagination of fallen minds—not in the structure of reality.

Biblical ontology resists all reduction. It is not speculative but revealed. To exist is to be spoken by God, to be sustained by Christ, and to be declared good—grounded not only in divine will but in divine character. This is an ontology of purpose, value, and permanence. It frames the world not as raw material to be reimagined, but as a moral order to be received, understood, and rightly inhabited. Creation is not merely a fact—it is a gift. And to live well within it is to live responsively, as one who has been summoned into a reality that is not only real, but right.

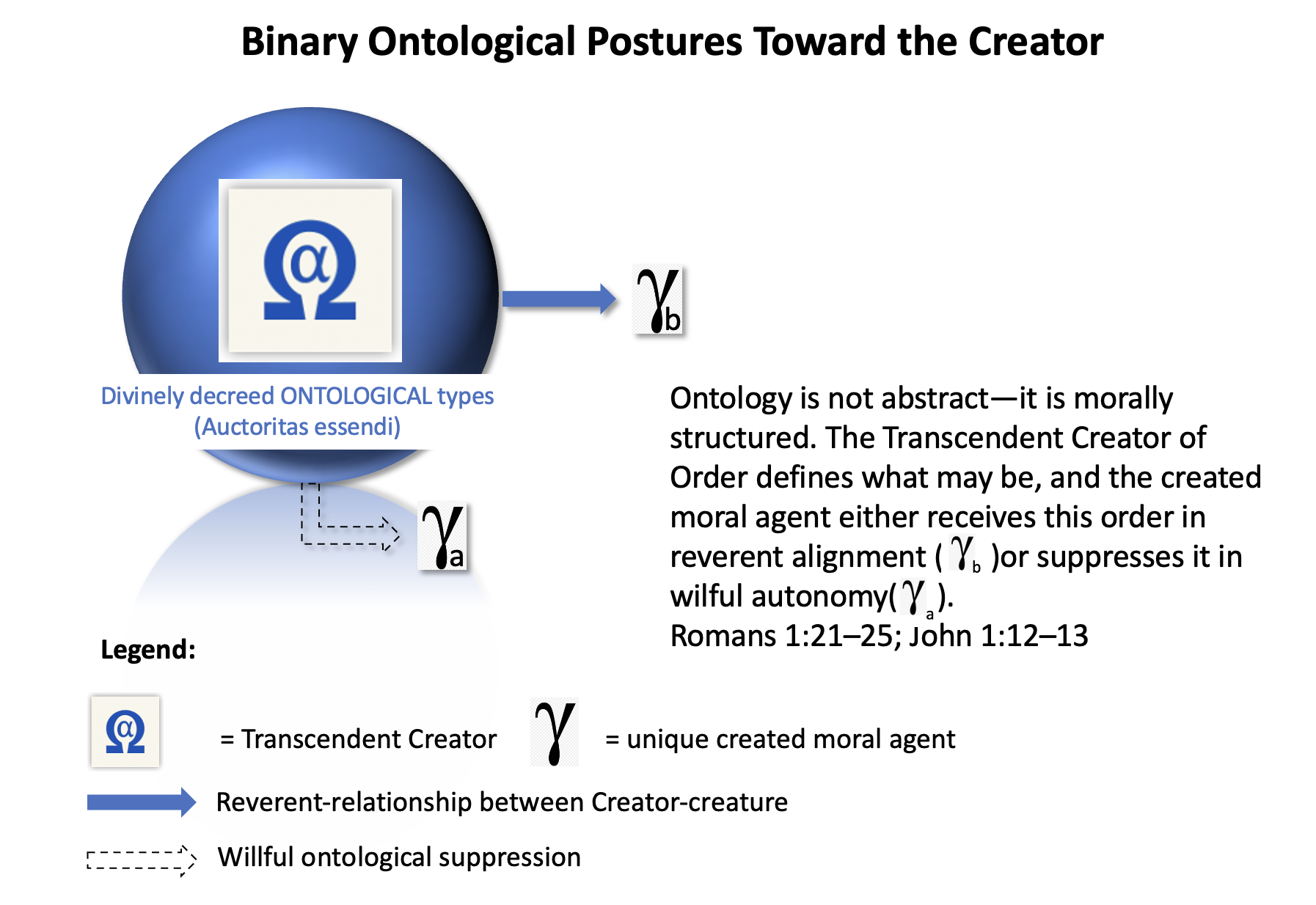

This framework affirms a relational ontology: that being is not an abstract category, but a state of alignment (John 17:3; Matt. 6:9–10) with the relational will of the Father and the begotten Son. Nothing truly is apart from God’s delimitation and instantiation—and no creature may rightly participate in reality except in moral relation to its Creator. Ontology, in this sense, is not static essence, but ordered participation in divine purpose. All existence, all value, and all truth flow from this relational dependence on God as the ground of being.

This implies that there are only two possible Transcendent–Creator / Anthropic–Creature relational postures: one of reverent ontological submission, and one of autonomous ontological suppression (John 17:3; Matt. 6:9–10). Every moral agent either receives being through relational ontological fidelity or asserts interpretive ontological autonomy apart from it. There is no ontological neutrality. The following diagram visualizes this binary relational structure.

If there are only two possible relational positions toward God—reverent ontological submission or autonomous ontological suppression (Romans 1:21; John 3:19–20)—then regeneration represents the decisive turning point: the moral agent’s restored alignment with the Creator’s decree of being. In this framework, biblical ontology is not primarily cosmological but covenantal. The most concrete expression of ontological realignment is not creation per se, but the regeneration of the believer, once the moral agent consents to restored relation (Acts 3:19; John 1:12–13).

The Gospel of John makes clear that Jesus does not use familial language merely as metaphor—He discloses an onto-typal reality: that the Son’s relation to the Father (the One True God) is the archetype of all restored being (John 5:19–20; 17:21–23). When believers are said to be “born of God” (John 1:13), this is not a symbolic resemblance to Christ’s sonship—it is a summons to ontological repositioning into that very filial structure. This invitation is not by nature but by grace: an adoption that results in ontological recategorization (Romans 8:15–17; Galatians 4:6–7). The believer does not merely imitate Christ’s relation to the Father—they are covenantally integrated into it, through the same Father who defines all kinds and grants all being.

This relation is not grounded in abstract authority but in relational posture: the begotten Son’s lived disposition of loving deference, ontological dependence, and perfect trust (John 5:19; 12:49–50). The Father–begotten Son relation reveals the very structure of relational ontology: not competition but unity, not autonomy but submission, not separation but participation. It is this filial pattern—revealed in Christ and extended to the believer—that constitutes the foundational reality into which all true being must be aligned.

Thus, regeneration is not merely moral reformation or legal pardon—it is ontological realignment. The believer is not simply reconciled; they are repositioned within the Creator’s relational order, through filial union with the Son. To be “in Christ” is not a metaphor but an ontic shift: the believer no longer defines or sustains their own being but inhabits a relational structure that is both covenantal and cosmic in scope (John 14:20; 2 Corinthians 5:17).

This adoption-based, filially realigned framework of relational ontology undergirds every subsequent claim in this model—regarding kind, instantiation, moral restoration, and the structure of redeemed reality. It is not abstract philosophy, but lived ontology: restored sonship through shared relation with the Father, mediated by the only begotten Son. This restored ontological order grounds the forthcoming moral analysis (axiology-deontology-modality), where value, duty, and modality unfold from the same divine prerogative.

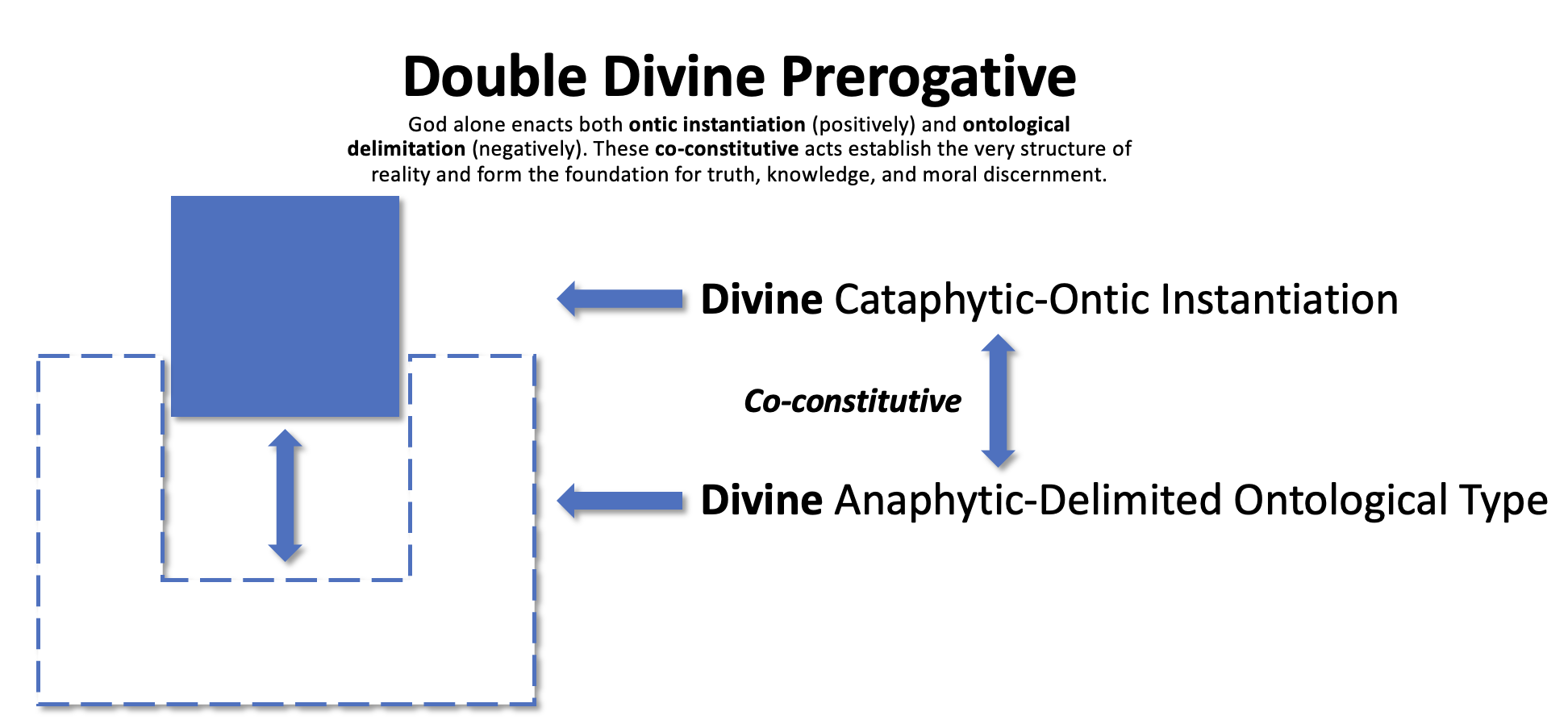

The biblical alternative to secular or symbolic ontologies does not begin with conceptual possibility or cultural coherence—it begins with the One True God. Specifically, it begins with the Creator's double prerogative: the exclusive right to define ontological kinds (auctoritas essendi) and to instantiate them into actual existence (auctoritas instantiandi). This twofold authority secures the coherence of all reality and underwrites the relational order that frames the entire biblical witness. Without this divine prerogative, there can be no legitimate ontology—only abstraction, simulation, or autonomous assertion. The relational structure described previously—what this framework terms relational ontology—rests entirely on this foundational claim: that only the One True God has the power to determine what may be, and to bring into being what He alone has decreed.

In this model, we start with terminology from Cornelius Van Til, who distinguished between God's cataphatic acts (assertive revelation and positive manifestation) and anaphatic prerogatives (boundary-setting, transcendence, and limit definition). We extend these categories into the realm of ontology, where:

Ontological delimitation is anaphatic: God defines the kinds and sets the outer boundaries of what may be.

Ontic instantiation is cataphatic: God brings those kinds into presence, whether as beings or as acts.

Before anything is, God defines what kinds of things may be. This act of delimitation is not conceptual or symbolic—it is ontological. It defines the anaphatic boundaries of each kind: the limits of what constitutes a lion, a human, a truth, or a just act. These boundaries are God’s own categorial judgments and decrees, embedded into the fabric of creation, and incorporate His axiological benevolence.

Ontological delimitation is thus the invisible structure of reality. It governs the permissible range of variation within a kind and sets its threshold against everything that is “other.” To redefine these limits is not to expand a category—it is to fabricate a new one, and to simulate an order that God has not authorized. Ontological fraud.

The definition of ontological kinds belongs to God alone—not as a logical deduction or cultural convention, but by sovereign ontological fiat. This is not merely a theological claim but an ontological assertion: only God possesses the auctoritas essendi—the authority to delimit what may be. Axiom: Ontological types exist by divine delimitation, not human deduction. This act is not shared—not even analogically. Ontological delimitation is the exclusive and untransferable act of God; no creature may define a kind.

At this point, the framework introduces a seven-fold diagnostic—detailed in the following essay ( Ontology Part II )—for discerning whether any proposed kind bears the marks of divine ontological legitimacy: Fixity, Integrity, Parsimony, Typological Convergence, Modal Implication, Telic Vector, and Divine Assignment.

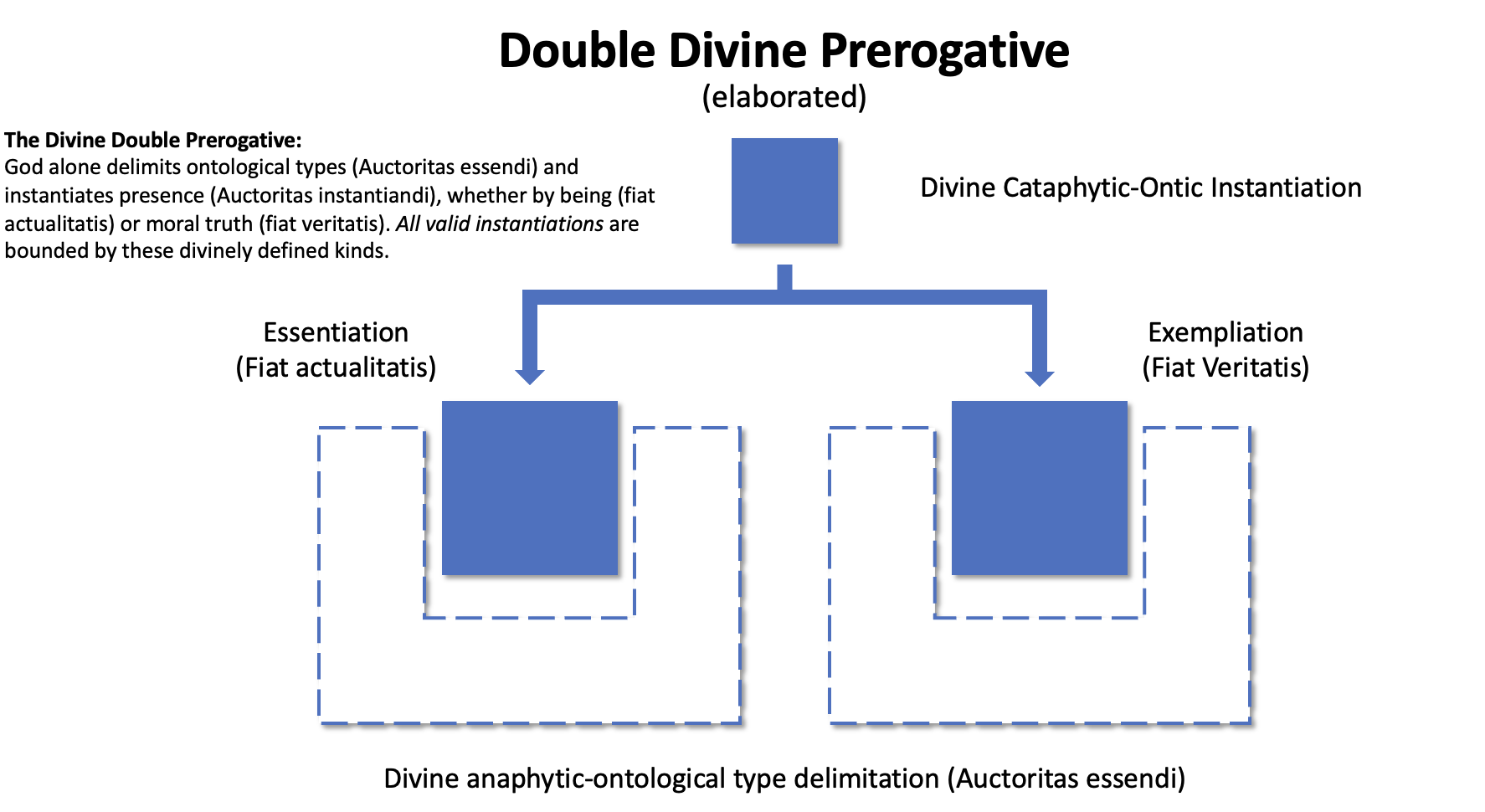

Delimitation alone does not confer presence. A kind may be divinely defined, but it does not exist until God instantiates it—either as a being (essentiation) or as a moral act (exempliation). Instantiation is thus cataphatic: the active projection of real presence into the created order. Anthropic agents do not bring new kinds into being; they merely participate in or exemplify the onto-typological instantiation that God alone enacts. This will be discussed in detail later (III.D.3.)

These two operations—delimiting kinds and instantiating presence—must be held together. To separate them is to open the door to ontological fraud: the attempt to simulate presence without authorization, or to name being without real instantiation.

In God, delimitation and instantiation are co-constitutive. God does not define in the abstract and instantiate later; His delimiting act already presupposes the conditions under which instantiation may occur, and His instantiating act always occurs within His established boundaries. This model prevents both conceptual inflation (creating types that do not correspond to real being) and performative fraud (claiming presence apart from God’s act). It forms the backbone of relational ontology: being is never self-sufficient, but always in relation to God’s will, judgment, and presence. However, most classical ontological models stop at the level of instantiation, treating it as a single, undifferentiated concept—something that “happens” when a universal is realized in a particular.

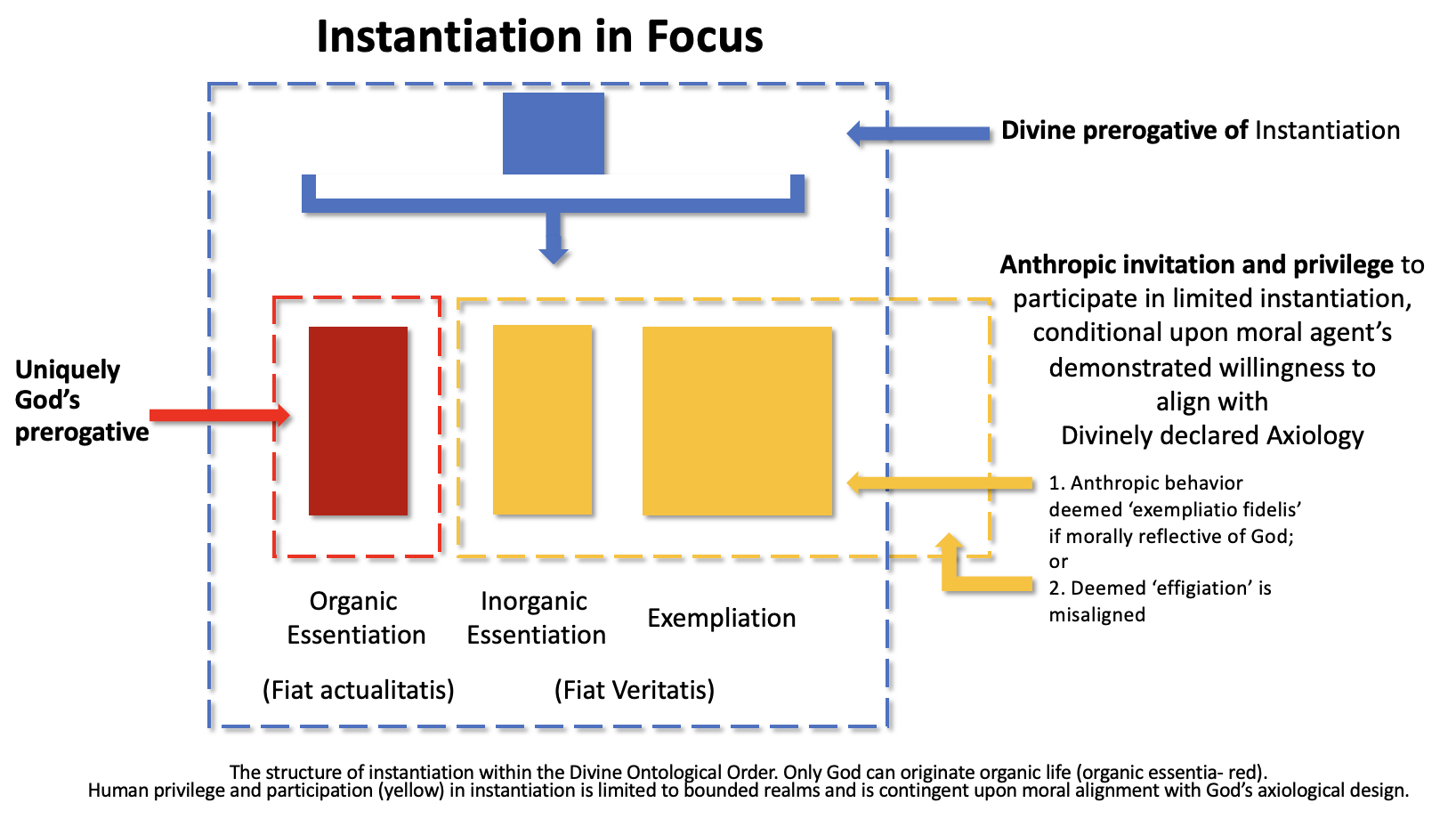

The diagram above illustrates our model so far.

The diagram above illustrates our model so far.

It should be noted that not all metaphysical traditions have treated instantiation as a neutral or merely logical operation. Thomistic metaphysics, for instance, affirms that existence (esse) is not intrinsic to essence but must be conferred by God through the actus essendi—the act of being. This insight establishes a crucial dependence of all created beings on divine will, and stands in continuity with the biblical notion that “in Him we live, and move, and have our being.” However, while Aquinas affirms that being is received, his model does not fully develop the relational or moral structure of instantiation. It treats creation as metaphysically ordered but does not explore how simulated instantiations, such as idols, institutions, or performative moral acts, might function as ontological fraud.

In contrast, Process thought, especially in the lineage of Alfred North Whitehead, presents reality as a dynamic unfolding of events or “actual occasions,” in which even divine action is seen as persuasive rather than sovereign. Here, instantiation becomes a cooperative or co-creative act, distributed across the field of becoming. While such models recognize relationality and moral dynamism, they do so by diluting divine prerogative and collapsing ontological sovereignty into participatory flux.

The framework developed here shares Thomism’s commitment to metaphysical realism and Process thought’s concern for relational coherence, but departs decisively from both. It insists that instantiation is not only metaphysical or dynamic, but morally accountable and ontologically bounded. Every being or act must answer not merely to order or relation, but to the Divine Double Prerogative: only God defines what may be, and only God authorizes what truly is. It is this structure that anchors the moral weight of being and the interpretive rigor of truth.

But in a moral and theistic universe, not all instantiations are alike. It matters who instantiates, what is instantiated, and how that manifestation occurs in space and time.

For this reason, we propose that ontic instantiation must be subdivided:

These distinctions are not semantic—they are ontological and moral realities. They govern how presence is assigned, how reality is discerned, and how truth and fraud are to be distinguished in the world. Our position so far is depicted in the diagram below:

Because God is not only Creator but also morally perfect, every act of instantiation, whether it be essentiation—fiat actualitatis— or exempliation (fiat veritatis) —are not merely ontologically valid, but also axiologically grounded. God does not instantiate being arbitrarily. What He brings into presence, He does so with benevolence, justice, and purpose, in alignment with His own nature.

In this framework, axiology is not a secondary property of things—it is intrinsic to their creation. The order of being is morally charged from its origin. What God delimits is wise; what He instantiates is good. This does not mean that every being is morally righteous (e.g., fallen angels, rebellious humans), but that its initial existence is always justified within the broader order of divine wisdom and sovereignty.

This is why instantiation is not morally neutral—it flows from God's character, not merely from His power.

It must be noted—particularly in light of the Gospels’ unfolding portrayal of divine judgment, regeneration, and kingdom invitation—that while the Divine Double Prerogative remains inalienably God's, Scripture reveals an anthropomorphic accommodation: a probationary and covenantal invitation for moral agents to participate analogically in the divine order. Analogical in contrast to univocal or equivocal: in likeness, by permission, and through alignment. This participation is never ontologically autonomous—it is conditional upon spiritual regeneration (John 1:12–13; Acts 3:19; 2 Pet. 3:9), and is measured by the agent’s willingness to align axiologically and deontically with the will of God (Micah 6:8; Romans 12:1–2; Heb. 5:14). Though this invitation allows for real participation, it is always mediated through filial union and spiritual dependence (John 14:20; 15:4–5), not self-derived. Analogical participation, therefore, is both real and bounded: morally responsive, covenantally summoned, and ontologically contingent on God's prerogative and grace.

Those who respond to divine revelation—through humility, repentance, and active moral exemplification—are granted the dignity of partial participation. They are entrusted with the stewardship—not as ontological originators, but as covenantal mirrors of God’s moral architecture. This is not mere permission; it is a relational entrustment, contingent upon continued fidelity. In this way, the biblical witness frames human agency not as creators of types or possessors of truth, but as responders and stewards within a divine order. Participation in the Divine Double Prerogative is possible, but only by grace, through alignment, and always under the condition of judged probation. These themes are explored further in later sections.

Scripture reveals that creation is not a flat domain of shared being, but a covenantally ordered reality structured by ontological hierarchy. While human beings are indeed invited to participate analogically in the divine order, that participation is relational, probationary, and bounded. “Let us make man in our image” (Gen. 1:26) establishes humanity not as autonomous or co-divine, but as a derivative reflection—called to represent God's character, not replicate His prerogative. This analogical likeness permits moral agency, relational engagement, and delegated stewardship, but not access to divine causality or self-existent being.

Through grace, humanity may become “partakers of the divine nature” (2 Pet. 1:4), yet this is a participation in moral renewal, not ontological elevation. We are “laborers together with God” (1 Cor. 3:9), but the labor is appointed, not self-initiated. Even our union with Him—“he that is joined unto the Lord is one spirit” (1 Cor. 6:17)—is covenantal, not consubstantial. God alone possesses aseity: “as the Father hath life in himself, so hath he given to the Son to have life in himself” (John 5:26). He is “not served by human hands, as though He needed anything” (Acts 17:25), nor is any creature indispensable to the divine order.

Scripture is unequivocal in drawing these boundaries. The Lord's interrogation of Job—“Where wast thou when I laid the foundations of the earth?” (Job 38:4)—exposes the ontological limits of all creaturely epistemology and agency. “The secret things belong unto the Lord our God” (Deut. 29:29), and “My thoughts are not your thoughts, neither are your ways my ways, saith the Lord” (Isa. 55:8). Human wisdom is not just insufficient; it is non-authoritative. As Paul writes, “Shall the thing formed say to him that formed it, Why hast thou made me thus?” (Rom. 9:20). To contest the order of being is not creativity—it is rebellion.

Indeed, the line of ontological authority is exclusive: “Who is he that saith, and it cometh to pass, when the Lord commandeth it not?” (Lam. 3:37). No decree, no enactment, no system of thought has existential validity apart from the Lord's command. All attempts to instantiate without divine warrant are exposed as effigiation—simulation without sanction, projection without essence.

Thus, while humanity is called into relational fidelity and ethical alignment, the limits of anthropic participation remain divinely defined. To cross them is not bold innovation—it is ontological transgression. To remain within them, in humility and covenantal trust, is the posture of faithful ontology.

First, to reiterate, the definition of kinds—what may be—is God’s alone (auctoritas essendi). No human or institution can invent a new ontological type without committing ontological fraud. This ontological distinction is first affirmed in the Genesis creation account, where God repeatedly creates and separates entities “after their kind” (Gen. 1:11–25). These kinds are not merely biological but ontological—establishing categories of being as part of the divine order. All legitimate instantiation follows this divine ontological type-delimitation.

Second, in the act of essentiation (instantiating being), we must distinguish between two subtypes—one reserved solely to God, the other involving conditional anthropic participation:

Inorganic Essentiation involves the construction or assembly of non-sentient entities (e.g., tools, artifacts, machines, institutions). God also creates non-sentient entities. Human fabrication, by contrast, is always limited to the reconfiguration of pre-existing matter or resources. Humans may “make” such things, but these acts do not create new ontological kinds—they operate within boundaries already delimited by God.

Human essentiation in the inorganic realm may be real (e.g., a bridge) or simulated (e.g., humanoid robots, idols)—but they never carry ontological originality. Inorganic essentia are bounded rearrangements, not genuine acts of ontic creation.

This form of anthropomorphic inorganic essentia—what we term effigiation—is not a true creation, but a projection of presence that mimics divine act without ontological weight. Whether embodied in technological agents, iconographic idols, or symbolic institutions, such effigiations simulate life or moral authority without bearing the divine seal of instantiation.

Third, in the realm of exempliation, both God (fiat veritatis) and humans may think and act—though in sharply distinct ways.

God exempliates truth, justice, and mercy not only through moral command but also through ontological revelation—both in historical acts (such as the Flood and the Incarnation) and in His continuing presence and governance. These acts are not symbols, but divinely authored realities that instantiate and reveal what God is and what is right. Moreover, God’s thoughts themselves exemplify moral rectitude. They are not neutral abstractions, but expressions of divine will consistent with His axiological character. Divine cognition is itself an act of moral alignment, and Scripture often reveals God's thoughts (Jer. 29:11; Isa. 55:8–9; Ps. 139:17–18) as covenantally oriented—disclosing His benevolent disposition toward humanity.

Humans likewise exempliate values—both through internal volitional postures (e.g., forgiveness, pride, hope) and through morally charged actions (exempliatio fidelis). But not all human exempliations are valid. Only those thoughts and actions that align with a divinely delimited ontological type, and are enacted with moral congruence—especially in motive—constitute faithful and true exempliations. We are invited to align our cognitive patterns with His: Isa. 55:8–9; Rom. 12:2; 1 Cor. 2:16; Ps. 36:9.

Exempliatio fidelis: A faithful act or presence that aligns with a divinely delimited ontological type. Not an innovation, but a moral echo.

When human acts or postures are misaligned—performative, deceptive, or ideologically inflated—they become pseudo-exempliations: gestures that mimic moral reality without corresponding to it ontologically.

This threefold clarification: ontological type definition; organic vs. inorganic essentia (true or effigiated), and true vs. false exempliation—is essential for distinguishing God’s creative prerogative from human imitation or assertion. It also provides a foundation for evaluating claims to meaning, presence, identity, and action across all disciplines.

In summary, exempliation includes both external acts and internal volitional postures (e.g., forgiveness, pride, hope), since both instantiate value and moral stance before God. Exempliation is not limited to the visible or performative; it includes intangible expressions of moral intent that nonetheless carry ontological weight. Not all thinking is exempliation, but all genuine exempliation is preceded by morally upright noetic intention. Internal states may therefore be morally exemplary or counterfeit, depending on their alignment with the divine axiological frame.

The following diagram depicts our substantial elaboration of Instantiation:

The above diagram presents a schematic illustration of the concepts introduced. The red subcomponent is God's prerogative alone: the yellow is that which there is a conditional anthropic invitation to faithful stewardship. Moral agents, as delegated co-actors within creation, participate in God’s order by rightly exemplifying moral acts and, secondarily, by essentiating inorganic forms in alignment with divine axiological order.

To speak truthfully is not merely to “mean well”—it is to speak in alignment with what God has delimited and instantiated. Human participation in truth-telling, action, or meaning-making is not autonomous. It is a granted privilege, extended only to those who are regenerated in spirit, morally aligned, and relationally submitted to the divine order. Scripture does not merely inform us—it conditions our right to participate in the ontological architecture of reality (John 8:47; 1 Corinthians 2:14–15; 2 Timothy 2:15–16; Romans 1:21–22, 25; Psalm 15:1–2; James 3:14–17.)

This participation, while real, is always derivative and probationary. It occurs within a moral covenant, under conditions of axiological alignment and teleological exemplification, and is subject to judgment. This posture—what we later describe in more details as noetic alignment—is the prerequisite for all faithful epistemology, morality, and speech. It is the ground of all accountability and the interpretive standard for the rest of this framework: we must not only discern what is said, but whether it corresponds to what is, and whether what is has been rightly delimited, rightly instantiated, and rightly received

Relational Ontology and the Divine Double Prerogative in Hierarchical Convergence

Relational ontology, as presented in this framework, is not an abstract theory of being—it is the structural expression of the biblical worldview’s ontological claim: that all being is received, not self-generated; defined, not imagined; relationally grounded, not autonomously emergent. Non-biblical ontology—whether philosophical, scientific, symbolic, or spiritual—ultimately collapses into abstraction, simulation, or self-referential incoherence because it severs being from its revealed source. Where secular models attempt to define being from below—through human perception, language, or consensus—relational ontology insists that true being is defined from above, through the will and word of God. What exists does so not because it is intelligible to man, but because it is willed by God and ordered according to His moral character.

In this light, relational ontology is not simply metaphysical—it is covenantal and moral. To exist rightly is to exist in right relation to God. The primary question is not What exists? but: How does anything exist rightly? The answer: by relational alignment with God’s declared will.

At the center of this relational ontology stands the Divine Double Prerogative (DDP). These are not speculative doctrines but operational truths that frame all legitimate being. No ontological type is valid unless God defines it. No real presence is legitimate unless God instantiates it. The DDP thereby exposes the illegitimacy of all ontological simulation—those systems that assert identity or presence apart from divine grounding. They may imitate structure, but they cannot confer substance.

The convergence of relational ontology and the DDP is not symmetrical, but hierarchical: the former defines the moral architecture of reality, while the latter secures its ontic integrity. Together, they establish a coherent foundation for all truth, moral agency, and epistemic responsibility.

Yet even this foundation is resisted. What follows in Ontology Part II interrogates the persistent suppression of this divine structure: how secular systems evade, displace, or counterfeit it—and how Scripture provides not only critique, but criteria, for recovering ontological clarity. Beyond this, the next section will trace how the rupture of being gives rise to a deeper epistemic crisis: when relation is severed, knowledge itself begins to recede.